Philadelphia Navy Yard

By Jim Saksa

Essay

The history of the Philadelphia Navy Yard has been one of constant struggle, repeatedly staring down imminent closure only to be saved at the last second by stalwart local politicians or a timely military conflict. Fondly remembered as the outfitter of the first American fleet, builder of the first warship under the Constitution, launcher of the largest U.S. battleships, and a frontrunner in aviation experimentation, a less nostalgic look back reveals the Navy Yard as a secondary naval facility throughout most of its active life. Over a period of 120 years, the yard laid keel and launched just seventy Navy and Coast Guard ships. The shipyard was used more to outfit, repair, and overhaul warships. As a naval base, it mainly served as home to the reserve fleet. After closing as an active yard and base in 1996, the Navy Yard rebounded in the twenty-first century as an office park employing eleven thousand people at the end of 2015—less than its peak of fifty thousand workers but close to its historical average.

During the eighteenth century, Philadelphia remained the most important economic city in the colonies and employed the most skilled shipwrights in the new nation. In 1801 the federal government established the Philadelphia Navy Yard in Southwark at the site of a shore battery built in 1748, toward the end of King George’s War (1744–48), which inspired its construction. The site was chosen in large part because it lay just outside the colonial limits of Old Philadelphia, where pacifist Quakers objected to such martial projects. Originally called Wicaco by the Lenni Lenape and settled by the Swedes, Southwark got its name in the 1760s after local shipbuilders petitioned the provincial government to rename the town after London’s famed shipbuilding district.

Just nine years after it opened, the Southwark Navy Yard faced its first shutdown scare when Congress debated closure in 1810. But British naval aggression, which soon led to the War of 1812, saved the nascent facility. This was the first, but far from the last, time foreign conflict proved fortuitous for Philadelphia’s naval firmament.

The war’s end brought renewed worries about imminent closure, held at bay only by the continued construction of the 74-gun Franklin, the Navy Yard’s first major warship, which launched before fifty thousand onlookers on August 21, 1815. The Southwark yard laid keel on another ship-of-the-line, the Pennsylvania, in 1821, but budget cuts delayed its launch until 1837. Redesigned into 136-gun, four-deck behemoth, the Pennsylvania was the U.S. Navy’s largest sailing warship. Ironically, it never saw combat, making just one voyage, from Philadelphia to Norfolk, where it laid up until burned in 1861 to keep it out of Confederate hands.

Production problems at Southwark’s small, out-of-date facilities were exacerbated during the Civil War (1861-65). The U.S. Navy’s shift to steam power was well underway when Fort Sumter was attacked in 1861, and the war triggered the development of ironclad warships. The cramped Southwark site lacked the space for the machine shops required to build state-of-the-art warships.

League Island Naval Yard

Fearing that the Navy would leave the city, Philadelphia’s political and business establishment offered a new site for the yard at League Island, at the confluence of the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers, which they proposed to sell to the federal government for a single dollar in 1862. Politics delayed the deal’s consummation for six years while New England congressmen sought to bring more shipbuilding jobs to their constituents.

In 1869, Camden, New Jersey lawyer George Maxwell Robeson (1829-97) became secretary of the Navy. The local Republican bigwig showered his shipbuilding friends along the Delaware with government contracts. For League Island, he also ordered the construction of a freshwater basin, new machine shops, foundries, and other more mundane improvements, like roads and residences. Blueprints for the new yard’s development drafted in 1871 guided construction for the next 125 years.

For eight years, the Navy operated the two yards simultaneously. As League Island’s facilities were built, the navy slowly shifted outfitting and repair work from the Southwark yard, which closed with great fanfare during the nation’s Centennial year in 1876.

Just a few years later, Philadelphia faced a future without a naval facility once again, when the Navy decided to close the new yard in 1883 after a corruption scandal involving falsified payment records. But the Navy dropped the plans, and the yard remained busy during a broader naval renaissance between 1881 and 1891 that saw renewed investment in building and expanding the American fleet.

But the lack of a modern industrial plant, machine tools, shipbuilding ways, and dry docks at the League Island site meant the Navy Yard did not build the new steel warships filling the reinvigorated navy’s ranks. Instead, those contracts went to private shipbuilders along the Delaware, who drew upon Pennsylvania foundries for steel and mines for coal. Even as facilities expanded in the 1890s, the Philadelphia Navy Yard assumed the role that became its primary purpose for most of its active life: an outfitting station and reserve fleet storage facility.

Despite a rush of improvements, the Navy Yard still was not a first-class shipbuilding facility when the sinking of the Maine heralded the Spanish-American War in 1898, but the Caribbean and Pacific conflict fueled its expansion: The back channel was dredged, officers quarters built (including the Commandant’s Office Building and the Marine Corps Barracks), and modern, steel shipbuilding shops constructed.

Philadelphia lacked a facility large enough for modern battleships until Dry Dock No. 2 was completed in 1907. A string of accidents and frequent groundings caused by the narrow channels and cramped waterways around League Island landed Philadelphia’s Navy Yard back on another closure list. However, objections to the reorganization raised by a group of naval officers stationed at League Island changed the mind of the new secretary of the Navy, George von Lengerke Meyer (1858-1918). Instead of closing the yard, he then authorized some of the most extensive improvements in its history.

World Wars: The Navy Yard’s Golden Years

Many of the buildings that give the modern Navy Yard its character were built before and during World War I, although the Navy Yard still lacked modern shipbuilding facilities heading into the war. Shipbuilding Ways No. 1 was not finished until June 1915, just months after the sinking of the RMS Lusitania. The new shipbuilding ways went into work immediately to build a marine transport ship, the Henderson, in line with the expanding Marine Corps Reservation at the base.

The Great War brought another expansion wave to League Island, which was effectively split into two: On the western side, a naval shipyard, known as the “new Yard,” with new dry docks, expanded shipbuilding ways, steel shops, a new foundry, and a 350-ton hammerhead crane, then the world’s largest; on the eastern side, a navy base with a new receiving station, training center, and the Marine Corps Reservation.

Around the same time, naval aviation facilities cropped up on League Island. The Aero Club of Pennsylvania had built a hangar and airfield on the island’s eastern end in 1910; seven years later, the Navy added a new hangar there, plus an aircraft factory. The aircraft factory and airfield, later named the Henry C. Mustin Naval Air Facility, focused mainly on seaplanes.

Despite the improvements, Philadelphia Navy Yard launched just two ships before the Armistice of November 11, 1918. The Reserve Basin once again filled with a mothball flotilla in the interwar period, and the workforce shrank from more than twelve thousand to roughly five thousand, with many put to work converting and scrapping old warships.

The Great Depression, a devastating event for most, signaled good news for the Philadelphia Navy Yard. New Deal programs brought funds to improve its physical plant. President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945), who previously had served as undersecretary of the navy, lavished funds on new warships, and Philadelphia turned out a dozen ships between 1934 and 1938.

The German invasion of Poland put sudden steel in the spines of Navy leadership, and the necessary upgrades to turn Philadelphia into a first-class shipbuilding facility were finally funded. Dry Dock Nos. 4 and 5 were built in 1941 and 1942, respectively. In 1940, work began on the battleship New Jersey, which went on to serve with distinction in World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, plus U.S. intervention in the Lebanese civil war, making it the most decorated battleship in U.S. history.

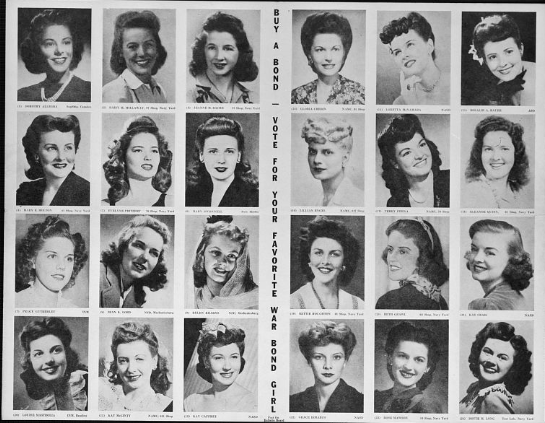

During World War II, the Philadelphia Navy Yard became a self-contained community, replete with its own sports leagues, bands, and newspaper. It was by far the Navy Yard’s most prolific period, when it built 48 new warships, converted 41 more, repaired and overhauled 574, completed and dry-docked 650, and outfitted 600. The Naval Aircraft Factory built 500 planes and the Receiving Station processed 70,000 Navy recruits. Over the course of 1941, the workforce rose from 24,000 to 33,000. In 1944 it hit 47,695 full-time civilian employees; adding in military officers and high school students in the summer, employment topped 60,000.

Unbeknownst to nearly all who worked there, the Navy Yard was home to experiments instrumental to the construction of the atomic bomb. In 1944, a wooden building storing uranium for the Manhattan Project exploded, killing two and burning nine. At the time, few noticed—industrial mishaps were common at the yard, given the frenetic pace of construction and thousands of hastily trained workmen. The Naval Boiler and Turbine Laboratory at the yard was used to separate U-235 isotopes from uranium ore to produce nuclear fuel. “Little Boy,” dropped by the Enola Gay on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, most likely used fissile material produced in Philadelphia.

The deadly accident, plus the Navy Yard’s proximity to Philadelphia’s large population, meant the base would never become a nuclear naval facility. Still, a small atomic plant at the Navy Yard operated until September 1945, and some of the research conducted at the Yard guided the construction of the U.S. Navy’s first atomic-powered submarine. These activities, plus rocket technology experiments and degaussing operations (demagnetizing ship hulls to protect against magnetic mines), may have inspired the urban myth of the U.S. Navy’s efforts to render a ship invisible, known as the Philadelphia Experiment.

Uncertainty returned to the Navy Yard following Japan’s surrender on September 2, 1945. During the Cold War, the newly renamed Philadelphia Navy Base and Naval Shipyard resumed its more traditional role as a port where ships were mothballed and overhauled. The workforce fell to nine thousand by July 1946. The Korean War brought another surge in work reactivating reserve warships. Research and development facilities also expanded, but the shipyard did not construct a single one of the 350 warships built during the conflict.

Vietnam brought another short-lived boom, reactivating more warships (including the New Jersey) and building a few more. But a congressional mandate in 1967 to move new ship construction to private yards meant that the Blue Ridge, a command ship launched in 1969, was the last U.S. naval vessel built at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. As of 2017, the Blue Ridge remained active, making it the oldest deployable warship in the U.S. Navy.

After Vietnam, the Philadelphia Navy Yard entered the slow, ebbing decline that led to its eventual closing in 1996. The Marine Corps Reservation closed in 1977, ending the Marines’ almost continuous 250-year presence in Philadelphia since its creation in 1775. Periodically, the entire Navy Yard faced closure, only to be saved by the efforts of the Delaware Valley’s congressional delegations.

Programs to upgrade older warships with state-of-the-art weapons systems kept the Philadelphia Navy Yard somewhat busy during the 1980s and 1990s, first with destroyers and cruisers in the Fleet Rehabilitation and Modernization Program, and later with the aircraft carrier Service Life Extension Program (SLEP).

In 1990, Philadelphia won its last SLEP contract, to overhaul the 80,000-ton aircraft carrier John F. Kennedy, which arrived in 1993 and stayed until work was completed in 1995. Despite the best efforts of local politicians—including a desperate lawsuit by Senator Arlen Specter (1930-2012) that Specter himself argued before U.S. Supreme Court—the base closed on September 26, 1996. Not everything shut down immediately. The Navy continued to operate the Propeller Manufacturing Center, the Inactive Ship Maintenance Facility, and the Philadelphia Naval Ship Systems Engineering Station.

After the closure, area politicians scrambled to recruit shipbuilding companies to use the Navy Yard’s large dry docks. Mayor Ed Rendell (b. 1944) pursued a deal with German shipbuilder Meyer Werft that fell through in 1995 after Governor Tom Ridge (b. 1945) rebuffed the proposal’s $167 million in government incentives as “pure fantasy.” Ironically, two years later, Ridge supported a more expensive deal to bring Norway’s Kvaerner (which later merged with Aker, adopting the latter’s name) to Philadelphia.

In 2000, Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC) acquired control of the Navy Yard’s remaining 1,200 acres and drafted plans to develop it into an office park. Following a master plan adopted in 2004, PIDC spent $150 million to improve the Navy Yard’s infrastructure. More than 150 companies opened offices at the Navy Yard, spending $750 million on private development—much of it to renovate historically significant naval buildings.

By 2017, more than twelve thousand employees worked at the Navy Yard, exceeding employment during any other point in the Navy Yard’s history except for World War II. PIDC’s 2013 update to the Navy Yard master plan called for even more private development, eventually to expand to 13.5 million square feet of office, industrial, laboratory, and commercial space employing thirty thousand people.

Jim Saksa is a reporter for WHYY’s PlanPhilly.

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- How the Navy Yard went high tech (WHYY, September 28, 2012)

- U.S. Senate committee moves to defund Philadelphia's Energy Efficient Buildings Hub (WHYY, July 2, 2013)

- PIDC charts a course for BSL extension to Navy Yard (PlanPhilly, March 27, 2015)

- A new neighborhood could rise at the Navy Yard if a plan comes together (WHYY, June 28, 2022)

Links

- Edwin Kendrick, Recollections of the Philadelphia Navy Yard during World War II, 1999. (Explore PA History)

- Navy Yard Equipment #14, Nov. 28, 1941. (Explore PA History)

- Fighting ships of the U. S. Navy moored alongside its famous hammer-head crane, Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, circa 1945. Second from left is the USS Wilkes-Barre; third from left is the USS South Dakota. (Explore PA History)

- Launching of the Battleship U. S. S. New Jersey, at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, Philadelphia, PA, December 7, 1942. (Explore PA History)

- At the Navy Yard, A Spectacular Speculative Office (Hidden City)

- The Navy Yard: An Office Worker's Paradise, Part I (Hidden City)

- Navy Yard: Contemporary Architecture, But Will It Add Up? (Part II) (Hidden City)