Poetry and Poets

Essay

Philadelphia boasts a rich history of poetry—poetry that describes intimate life experiences as well as an evolving history of immigration and colonization, urban growth and decline. Indeed, from the colonial era to the twenty-first century, poetry often stood at the center of civic life, fully engaged with the public sphere. The poetry of Philadelphia, reflecting in many ways the country’s larger currents, documents in detail the fate of the city and its shifting cultural politics.

Shortly after William Penn (1644-1718) founded the city of Philadelphia in 1682, Francis Daniel Pastorius (1651-c. 1720), often referred to as Pennsylvania’s first poet, arrived in Philadelphia in 1683. The founder of Germantown, Pastorius, whose poetry mostly survived only in manuscript, wrote of his emigration to Philadelphia and settlement on land bought from Penn in a poem titled “A Token of Love and Gratitude” that looked back on his years “In this then uncouth land, & howling Wilderness.” In another of his poems, he again recalled the city’s humble origins, remembering in heroic couplets a time “When the Metropolis (which Brother-Love they call,) / Three houses, & no more, could number up in all.”

Other poems from these early years actively sought to promote the city and its native resources. William Bradford (1590-1657), the first printer of the middle colonies, published a boosterish pamphlet poem by Richard Frame (“A Short Description of Pennsylvania”) in 1692 and another by John Holmes (“A True Relation of the Flourishing State of Pennsylvania”) in 1696. Before moving to New York in 1693, Bradford played a crucial role in founding the literary culture of Philadelphia. In 1685 he published one of the first American almanacs—America’s Messenger—with verse as a staple ingredient. When Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) started Poor Richard’s Almanac (1732-58), it was chock full of witty, proverbial poetry. Franklin even wrote some of it himself.

This poetry of self-improvement stood beside a poetry of praise in colonial Philadelphia. “A Memorial to William Penn” (1729), a declaration of cultural independence written by George Webb a little more than a decade after Penn’s death, appeared in the form of stanza headers for the months of the year in The Genuine Leeds Almanack for the Year of Christian Account 1730, published by Franklin’s rival Titan Leeds (1699-1738). Webb’s poem paid tribute to the city’s founder and the city’s civilized success, forecasting that “Europe shall mourn her ancient Fame declin’d / And Philadelphia be the Athens of Mankind”; in much the same way, so did Thomas Makin’s “A Discription of Pennsylvania” (1728) and Jacob Duché’s (1737-98) “Pennsylvania: A Poem” (1756).

When not singing the praises of the city or its citizens, poetry of the period commemorated those who had died. The printer-poet Samuel Keimer (1689-1742), who employed Franklin, wrote an elegy for another successful printer-poet, Aquila Rose (1695-1723), who worked in Bradford’s printing office and died at the age of 28. His 1723 broadside Elegy on the Death of Aquila Rose was Franklin’s first known printing job, and Franklin described the circumstances of its publication in his Autobiography, where he commends Rose as “a very tolerable poet.” (Rose’s posthumous Poems on Several Occasions—published in 1740 and known as the first American poetry anthology—includes elegies by and about him.)

The merchant and scrivener Joseph Breintnall (c. 1695-1746), an original member of the Junto, Franklin’s club for mutual improvement, also paid tribute to Rose before his untimely death; in “An Encomium to Aquila Rose, On His Art in Praising,” he wrote of Rose’s importance in elevating Philadelphia, claiming that “Strangers far remote will come” to Philadelphia, “And visit us as ancient Greece or Rome.” In another poem, “A plain Description of one single Street in this City” (1729), written as part of Franklin’s Busy-Body essay series, Breintnall described a walk on Market Street from the Delaware River to the Schuylkill, effectively mapping the geographical coordinates of the expanding commercial city.

Another member of Franklin’s Junto, George Webb, to whom Franklin taught the art of printing, wrote “Batchelor’s Hall: A Poem,” published by Franklin in 1731. Batchelor’s Hall, near Allen and Shackamaxon Streets in Kensington, was a learned society similar the Junto, but it had a reputation for licentiousness. In the poem, Webb, a member of the society, celebrated it (“the proud dome on Delaware’s stream”) and defended it against such charges, insisting that it was designed to allow men to be sociable and to train their minds on “nobler thoughts” in “the sweets of country air.” Philadelphia astronomer, mathematician, surveyor, and poet Jacob Taylor’s (?-1746) praise poem “To George Webb” hailed Webb as a powerful intellectual force, and contended, along with Webb, that the Muses had fled the Old World for Philadelphia.

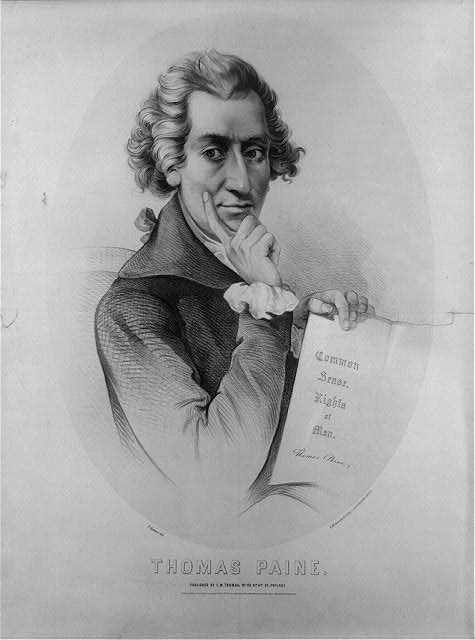

In 1775, fire reduced Batchelor’s Hall to rubble. Thomas Paine (1737-1809) wrote about the loss in a poem titled “Impromptu on Bachelor’s Hall, at Philadelphia, being destroyed by Lightning, 1775.” Webb’s earlier defense of the activities in the building did not stop Paine from asserting that it was a place where “Venus disclosed every fun she could think of, / And Bacchus made nectar for mortals to drink of,” and he interpreted the destruction of the building as divine punishment.

Other poets of the day also wrote about the evolving social sphere in the city and its environs. Notably, Henry Brooke (1678-1736) became the unofficial laureate of a group of gentry youth (his so-called “bottle-friends” as he termed them in a poem “writ at Newcastel in company”) who gathered often at Story’s Tavern at Front and Market Streets.

Another collective of poets and playwrights, the Swains of the Schuylkill, gathered at Philadelphia College (later the University of Pennsylvania) and were led by provost William Smith (1727-1803), who edited the American Magazine. This group included Francis Hopkinson (1737-91), Thomas Godfrey (1736-63), Nathaniel Evans (1742-67), and Jacob Duché (1737-98), who couched much of their poetry in the pastoral tradition; they met regularly on the banks of the Schuylkill at the “Baptisterion” (the Oak Grove at the end of Spruce Street).

The Swains participated in the salons of poet Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson (1737-1801), who wrote under the pseudonym Laura, at Graeme Park, seventeen miles north of Philadelphia in Horsham, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. Fergusson described Philadelphia as “the Athens of North America” and wrote on enlightenment themes; she cultivated a social network of female poets, including Susanna Wright (1697-1784), Annis Boudinot Stockton (born in Darby, Pennsylvania, 1736-1801), and Hannah Griffitts (1727-1817), who shared their poetry with each other in manuscript. Fergusson’s niece, Anna Young Smith (1756-1780), also a Philadelphia poet, wrote frequently on gender and politics as well as on the more conventional subjects of courtship, sensibility, and grief.

The Revolutionary War and the Early National Period

In addition to his proverbial almanac verse, in the years prior to the War for Independence Franklin wrote propagandistic political poetry. In “On the Freedom of the Press,” included in Poor Richard’s Almanac in 1757, he reminded that “The Press from her fecundous Womb / Brought forth the Arts of Greece and Rome.” Paine’s rousing song “Liberty Tree,” published in Pennsylvania Magazine in July 1775 under the pseudonym “Atlanticus,” also sounded the note of freedom: “From the east to the west blow the trumpet to arms, / Thro’ the land let the sound of it flee, / Let the far and the near,—all unite with a cheer, / In defence of our Liberty tree.”

The Quaker poet Hannah Griffitts, whose nom de plume was “Fidelia,” also wrote political poetry (as did Fergusson), emphasizing the role women could and must play in the defense of freedom. In “The Female Patriots” (1768) she called on “the Daughters of Liberty” to “nobly arise, / And though we’ve no voice, but a negative here,” vigorously oppose the Stamp Act of 1765 and Townshend Duties of 1767 and boycott British goods: “rather than Freedom, we’ll part with out Tea.” One of the Swains, Francis Hopkinson, penned “The Battle of the Kegs,” a propaganda ballad describing an attack in the harbor of Philadelphia upon a British fleet during the war. His son Joseph Hopkinson (1770-1842) composed “Hail Columbia” (1798), which became one of the nation’s favorite patriotic songs.

In addition to this politically inspired poetry, Philadelphia was flush with verse that described and often lampooned the character of its citizens, as growing wealth led to a perceived putting on of airs and attendant foolishness. “The Manners of the Times: A Satire in Two Parts” (1762), by “Philadelphiensis,” and the anonymous “The Philadelphiad” (1784), both in heroic couplets, satirized such stereotyped figures as the “Country Clown,” the “Quaker,” the “Emigrant,” and “Miss Kitty Cut-a-Dash; Or the Arch-street Flirt.” The Country Clown, for one, cautions: “Keep from the city and secure thy fame”; lurking in the city, he contends, are temptations steadfastly to be avoided.

Another poet of the Revolution, Philip Freneau (1752-1832), lived and worked in Philadelphia off and on, including during the 1790s, when he edited a partisan newspaper while the city served as the nation’s capital. He penned “On The Death of Dr. Benjamin Franklin” to commemorate Franklin’s passing in 1790, holding him up as an exemplar in all ways:

When monarchs tumble to the ground,

Successors easily are found:

But, matchless FRANKLIN! what a few

Can hope to rival such as YOU,

Who seized from kings their sceptered pride,

And turned the lightning darts aside.

In 1793, when yellow fever broke out in Philadelphia, killing a quarter of its residents, Freneau’s poem “Pestilence: Written During the Prevalence of a Yellow Fever” (1793) mourned the casualties of the epidemic:

Hot, dry winds forever blowing,

Dead men to the grave-yards going:

Constant hearses,

Funeral verses;

Oh! what plagues–there is no knowing!

The poem went on to decry “O, what a pity, / Such a City, / Was in such a place erected!” as the outbreak of yellow fever brought home the dangers of high-density city living.

The Nineteenth Century

The continuing expansion of Philadelphia and increases in its citizens’ wealth, and with it the breeding of waste, pretension, and extravagance, remained a target of verse satirists into the nineteenth century. In “Philadelphia: A Satire” (1821), John Cadwalader McCall (1793-1846) poked fun at the newest generation of city dwellers. In contrast to the esteemed origins of the city (“Thee, city of sonorous name, I sing, / The western Athens, and fair Fashion’s spring”), it now teemed with corrupt lawyers and dandies, “With fashions, scandal, and with folly fraught.”

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-49), who lived in Philadelphia from 1838 to 1844, tapped into the underworld of the industrial city—imagined as a zone of danger and terror—and, along with short stories, published several gothic poems during this period, including “Ligeia”(1839), about the death of a young woman, and “The Haunted Palace” (1843). He also conceived of “The Raven,” published in January 1845, in Philadelphia.

Poetry documented racial tensions during this period as well. In May 1838 an anti-abolitionist mob burned down Pennsylvania Hall, a large building on Sixth Street in Philadelphia constructed to serve as a headquarters for the antislavery movement, the same weekend it opened. Well-known abolitionist poet and Quaker John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-92) delivered the dedicatory poem, reminding the audience of the glory of the occasion, that although “loftier Halls, ’neath brighter skies than these,” once stood in Athens, “Yet in the porches of Athena’s halls, / And in the shadow of her stately walls, / Lurked the sad bondsman, and his tears of woe.” After the destruction of Pennsylvania Hall, Whittier responded in his poem “The Relic,” written in 1839 when he received a cane made from a fragment of the building’s woodwork:

The fire-scorched stones themselves are crying,

And from their ashes white and cold

Its timbers are replying!

A voice which slavery cannot kill

Speaks from the crumbling arches still!

Although abolitionism was controversial in Philadelphia, the city produced much poetry supporting the cause. In 1831, a group of African American women formed the Female Literary Association, a self-improvement society where writing, including poems, addressing contemporary social and political issues were read without author attribution at weekly meetings and later published anonymously in such outlets as the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator published in Boston by William Lloyd Garrison (1805-79).

John Collins (1814-1902) wrote a long poem about a fugitive-slave mother that was published for the 1855 Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Fair in Philadelphia. The Anti-Slavery Alphabet had been produced for the same fair in 1846: “A is an Abolitionist— / A man who wants to free / The wretched slave—and give to all / An equal liberty.” Famed African American poet Frances E.W. Harper (1825-1911) lived in Philadelphia throughout much of the 1850s and aided William Still on the Underground Railroad. She settled again in Philadelphia in 1870. One of her best-known poems, “The Slave Mother,” written in Philadelphia in 1854, made a strong sentimental case against slavery by depicting in ballad stanzas the heartbreak of a mother whose son is ripped from her and sold to another master.

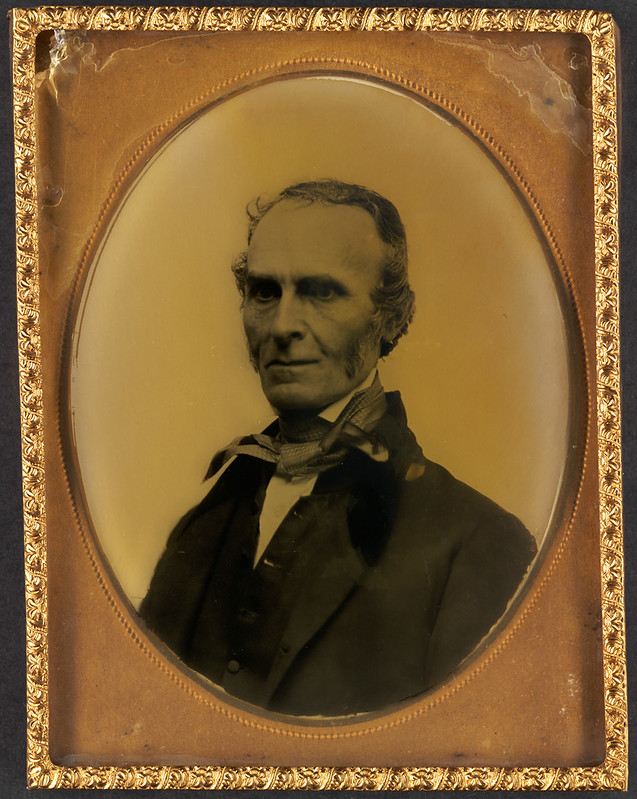

When the Civil War broke out, Philadelphia had its share of poets documenting that convulsive event and beating the drum for the Union cause. Perhaps the two leading poets in the city were Thomas Buchanan Read (1822-72) and George Henry Boker (1823-90). Read, born in Chester County, joined the Union army and penned one of the most popular poems of the war, the martial ballad “Sheridan’s Ride.” Boker, a leading spirit behind the city’s Union League Club, published Poems of the War in 1864. A good friend of Boker, Bayard Taylor (1825-78), born in the village of Kennett Square in Chester County, also composed Civil War verse, and to commemorate the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Monument at Gettysburg in 1869 produced “Gettysburg Ode,” a setting of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address to rhyme.

Poetry also marked the nation’s centennial in 1876, when Taylor was chosen over Walt Whitman (1819-92) to write and perform the poem for the Centennial Exhibition held in Philadelphia. A crowd gathered in Independence Square to hear him recite his poem, “Centennial Ode”:

Transmute into good the gold of Gain,

Compel to beauty thy ruder powers,

Till the bounty of coming hours

Shall plant, on thy fields apart,

With the oak of Toil, the rose of Art!

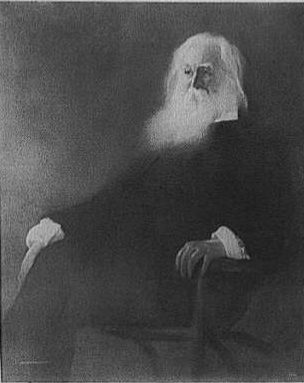

Walt Whitman had arrived in Camden, New Jersey, in 1873 from Washington, D.C., and, while in Camden produced several editions of his monumental, ever-evolving book Leaves of Grass in addition to several other timely books of poetry and prose, as his reputation as one of the greatest American poets began to be cemented. In his 1876 book Two Rivulets (the second volume of his Centennial edition of Leaves of Grass), published in Camden, Whitman included his Centennial Exhibition poem, “Song of the Exposition,” wherein he bids the Muse to “migrate from Greece and Ionia” to Philadelphia.

Upon his death in 1892, poets feted Whitman in verse much as Penn and Franklin had been before him. As native Philadelphian Francis Howard Williams (1844-1922) remarked in his commemorative sonnet “Walt Whitman” (March 26, 1892), “Darkness and death? Nay, Pioneer, for thee, / The day of deeper vision has begun; / There is no darkness for the central sun / Nor any death for immortality.”

The Twentieth Century to the Twenty-First Century

By the twentieth century, the poetic capital of the East Coast in many ways moved to New York City, at least in part due to the shift of the publishing industry. However, Philadelphia continued to host poets who weighed in on important matters of the day.

One of Whitman’s ardent disciples, socialist poet Horace Traubel (1858-1919), lived in Camden and worked as a publisher on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia. His journal The Conservator sought to keep Whitman’s legacy alive and included Traubel’s socialist free verse in the Whitmanian tradition. Traubel also wrote poetry staunchly opposing American involvement in World War I. Another poet well-known at the time, Germantown resident Florence Earle Coates (1850-1927), took the opposite view, describing the selfless sacrifices made by soldiers and citizens for the cause of freedom and liberty in a pamphlet of poetry called Pro Patria (1917). In 1915, Florence was unanimously elected Poet Laureate of Pennsylvania by the state’s Federation of Women’s Clubs.

In addition, some of the most important avant-garde poets of the period lived in and around Philadelphia, if only for a short while—notably, Hilda Doolittle (H.D.) (1886-1961), Ezra Pound (1885-1972), William Carlos Williams (1883-1963), all of whom were friends, and Marianne Moore (1887-1972).

African American poets also gained prominence as migration from the South added to the black population of northern cities, including Philadelphia, which had the second-largest African American population in the country by 1924. Alain LeRoy Locke (1885-1954), a native of Philadelphia, moved on to Harlem and became instrumental in leading the New Negro Movement, which lay at the core of the Harlem Renaissance. Another Philadelphia native, Jessie Redmon Fauset (1882-1961), worked on Black Opals (1927-28), a Philadelphia literary journal and club for young black writers, as did the poets Idabelle Yeiser (1897-?) and Mae Virginia Cowdery (1909-53).

The same spirit, but in more brazen language, characterized the poetry of Sonia Sanchez (b. 1934), a native of Alabama who moved to New York with her family during the 1940s and then taught in San Francisco before settling in Philadelphia in 1976. She became chairperson of the Department of English at Temple University the following year and served as Philadelphia’s first Poet Laureate in 2012-13. In “Elegy: For MOVE and Philadelphia” (1987), she mourned the casualties of the 1985 city bombing of MOVE, a black liberation group, in West Philadelphia.

Sanchez wrote poems about bleak cityscapes, and her words sometimes were written onto them. The City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, working with Sanchez in collaboration with Philadelphia’s third Poet Laureate, Yolanda Wisher (b. 1976), in 2012 launched a project titled Peace is a Haiku Song, to engage the Philadelphia community in exploring haiku as a vehicle for peace and urban transformation. Her haiku, included in a mural on the side of a building at 1425 Christian Street, reads:

The sprawling sound

of peace sails on the wind

A white butterfly

Her 1969 poem “Ballad” was scrawled across the façade of an abandoned house at Broadway and Ferry Avenues in Camden.

The power of poetry to comment on and entangle itself in the fabric of the urban experience also infused the work of Camden resident Nick Virgilio (1928-89), who produced radically remodeled urban haiku, often vividly set in the deindustrialized landscape of Camden:

moonlit city lot

strewn with sticks and broken bricks:

stray kitten licks wound.

Other poets examined Philadelphia’s past and its legacies. One of its most famous recent poets, the 1973-74 Poet Laureate of the United States Daniel Hoffman (1923-2013), wrote a book-length historical poem about William Penn titled Brotherly Love (1981), a finalist for the National Book Award in 1982. In its sixty-one poems, all in different styles, Hoffman relied on a range of primary sources to probe William Penn’s identity, putting into context his attempt to found a New Jerusalem in the wilderness. As a recurring theme, the book explored ways of knowing the past. Another poet associated with the University of Pennsylvania, C.K. Williams (1936-2015), in “The United States” (2007) spins an allegory about globalization and the decay of the American dream, as he attends to the “rusting, decomposing hulk” of the SS United States “moored across Columbus Boulevard from Ikea, / rearing weirdly over the old municipal pier / on the mostly derelict docks in Philadelphia.” In the poem, Whitman even makes a cameo appearance.

The work of African American poet Major Jackson (b. 1968), a native of North Philadelphia, also centered on this theme by exploring the politics of identity, specifically what it means to be a young poet of color in the city in the twenty-first century. His first book, Leaving Saturn (2002), winner of the 2001 Cave Canem Poetry Prize and finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award, was firmly rooted in Philadelphia: “I pledged / my life right then … / to anointing streets I love with all my mind’s wit.” In “Urban Renewal” he extends Hoffman’s critique by invoking “Penn’s GREEN COUNTRIE TOWN” only to show how that pastoral ideal has faded from view, leaving a “cracked republic.”

Issues of industrialization and racism, of the consequences of urban renewal and decline, also shaped David Livewell’s Shackamaxon (2012). Set in North Philadelphia, the book received the T.S. Eliot Prize. With similar concerns, that same year Lamont Steptoe (b. 1949) published Meditations in Congo Square (2012), focused on Washington Square, where African Americans were buried in unmarked graves in the eighteenth century, showing how the city is still haunted by its history.Other contemporary poets who have imagined the city and its pain and promise include Frank Sherlock (b. 1969), former Poet Laureate of Philadelphia (2014-15), and co-writer CAConrad (b. 1966), who penned the book-length poem The City Real and Imagined (2010) based on their walks through Philadelphia; Ryan Eckes (b. 1979), whose Old News (2011) looked into Philadelphia’s past through the lens of old news articles from The Evening Bulletin and The Philadelphia Inquirer; Jena Osman, whose Public Figures is a poem-essay that tracks the gaze of a number of statues in Philadelphia; and Yolanda Wisher, who in Monk Eats an Afro (2014) summoned “the hot breath of West Philly.”

In the early twenty-first century Philadelphia supported a vibrant spoken word scene as well as an epicenter of avant-garde poetry writing at the University of Pennsylvania. In its many forms, the poetry of Philadelphia has taken account of the social and political life of the city and its cultural memory, testifying to the importance of poetry to public life. Reading it, we get a keen sense of the evolution of the city and its place in a changing nation.

Tyler Hoffman (Ph.D., English, University of Virginia) is Professor of English at Rutgers University-Camden. He is the author of Robert Frost and the Politics of Poetry (2001), Teaching with The Norton Anthology of Poetry: A Guide for Instructors, 5th and 6th editions (2005; 2018), American Poetry in Performance: From Walt Whitman to Hip Hop (2011); co-editor of “This Mighty Convulsion”: Whitman and Melville Write the Civil War (2019); and numerous articles on modern American poetry and culture.

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- PhillyPoetry.org

- Philadelphia Youth Poetry Movement

- Philadelphia Poet Laureate (Free Library of Philadelphia)

- Francis Daniel Pastorius's Description of Pennsylvania of the 1690s (PDF, National Humanities Center)

- Nathaniel Evans: Verses Addressed to Benjamin Franklin (National Archives)

- The Poems of Philip Freneau (E-book, Project Gutenberg)

- Hannah Griffits, "Upon Reading a Book Entitled Common Sense" (PDF, National Humanities Center)

- The Raven, Hand-Written Manuscript by Edgar Allan Poe (Free Library of Philadelphia)

- Edgar Allan Poe's Most Productive Years (National Park Service)

- The Walt Whitman Archive

- Centennial Ode, by Bayard Taylor (Archive.org)

- Peace is a Haiku Song (Mural Arts Philadelphia via YouTube)

- Nick Virgilio Haiku Association