Revolutionary Crisis (American Revolution)

Essay

The Stamp Act of 1765, the first direct tax ever imposed by the British government on colonial Americans, inadvertently provoked a ten-year clash of wills between Britain and the colonies that led to the American Revolutionary War. During this Revolutionary Crisis period (1765-75), colonists resisted imperial taxes and other Parliamentary innovations with protests and with boycotts of British goods, called nonimportation agreements. Many Philadelphians initially proved more reluctant to join the protests than colonists to the north and south. However, with much of the trade of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and parts of New York flowing through the city’s port, Philadelphia became a central focus for enforcing nonimportation. Ultimately, popular anger over British “encroachments” forced a realignment of power in the town and province and brought Philadelphia-area merchants and consumers into greater support for the resistance movement.

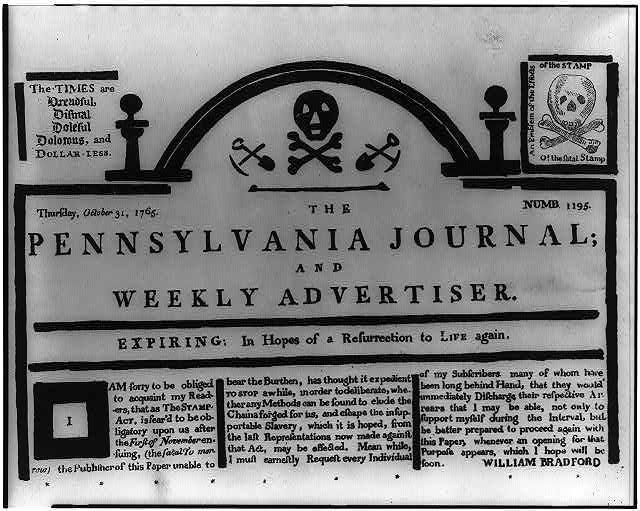

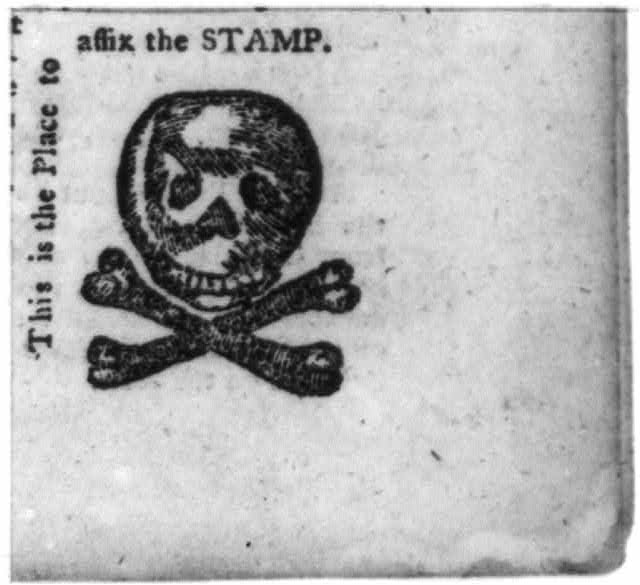

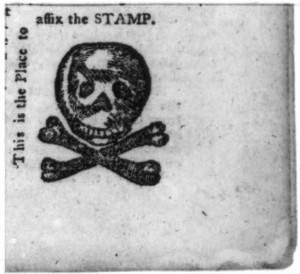

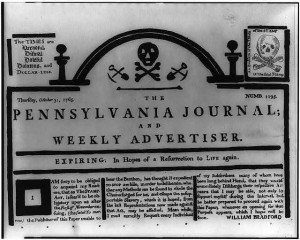

Britain’s Parliament passed the Stamp Act on March 22, 1765, to offset the huge debt amassed during the recent Seven Years’ War (1754-63). The British government intended the Stamp Act to defray the cost of “defending, protecting, and securing” the “British colonies and plantations in America.” The terms of the act required colonials to purchase special paper from designated commissioners for a wide variety of legal and business transactions, varying from court pleadings and wills to newspapers and gaming cards. Contracts written on other than stamped paper were null and void, and counterfeiting the stamps was deemed a capital offense.

The British government seriously underestimated the anger this law would provoke. Colonial “Patriots” argued that cooperation with the law, which imposed taxation without American representation in Parliament, was akin to accepting economic slavery. Major riots occurred in Boston and New York City. Colonial legislatures and newspapers issued strongly worded protests. A German-language press in Germantown encouraged readers to resist the unerträglichen (“unbearable”) Stamp Act. Everywhere, angry mobs targeted royal officials; the Constitutional Courant (Woodbridge, New Jersey) called American-born men who would cooperate with such an act the “vipers of human kind,” and the “worst of parricides.” In October 1765, nine of the thirteen colonies sent representatives to a Stamp Act Congress in New York City to draft a unified protest.

In comparison with other colonial cities, Philadelphia’s initial response to the crisis was mild. While other colonial assemblies took a leading role in organizing the resistance, Pennsylvania’s assembly, dominated by the “Quaker” Party of Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) and Joseph Galloway (1731-1803), remained caught up in a struggle to wrest the colony from the Penn family. Franklin, serving in London at the time as colonial agent, so misjudged colonial response that he recommended a trusted colleague, John Hughes (1711-72), for the post of Pennsylvania stamp act distributor.

Philadelphia’s Muted Protests

Franklin’s popularity among the mechanics and artisans muted Philadelphia’s protests, but both he and Hughes were castigated for their apparent support of the unpopular measure. On the night of September 16, 1765, a large mob gathered at the State House to target individuals associated with the act, including Franklin, Hughes, and Galloway. Franklin’s wife, Deborah Read Franklin, (1708-74) reported to her husband that the crowd was dissuaded from attacking the Franklin home by an association of over 800 men formed “for the Preservation of the Peace of the City,” who convinced the protesters to disperse. Once the stamps themselves arrived on October 5, another huge crowd corralled stamp distributor Hughes and made him swear not to execute the act or permit the stamps to be unloaded.

Pennsylvania’s rival Proprietary Party also tried to use the controversy to politically weaken Franklin, blaming him for not trying to halt the legislation. Franklin’s supporters countered that no American could have successfully held off the Stamp Act, given its broad Parliamentary support. One broadside signed by “A Freeman of Pennsylvania” claimed: “Mr. Franklin, or any other American…might as easily have stopped the tide of Delaware, at New Castle, with his Finger, as prevented the Bill passing into a Law.”

Amidst the riots, congresses, petitions, and threats, the most potent form of protest was a new type of resistance action: colonial boycotts of British goods. Called “nonimportation agreements” (when merchants signed them) and “nonconsumption agreements” (when citizens signed them), these agreements were the first large-scale boycotts in history. Made possible by colonial Americans’ growing importance as British consumers, they were promoted through colonial newspapers and broadsides that encouraged readers to show patriotic resistance to the unjust acts.

Philadelphia’s merchants pledged cooperation with nonimportation, albeit somewhat reluctantly. Philadelphia docks tried to unload all ships by November 1, 1765, the date when the Stamp Act would go into effect, accordingly preserving “October 31” on their forms as an unloading date for several weeks—if a ship had begun to be unloaded by Halloween, it was “grandfathered” under the pre-act terms. As late as December, ship-owners still received port authorities’ go-ahead to clear ships, under the fiction that the stamps were somehow inaccessible. Even Philadelphia’s vermin reportedly assisted the resistance effort, as one newspaper gleefully reported: “a Quantity of the Stamp Paper, on board the Sardoine Man of War, has been gnawed to pieces by the Rats!”

The Stamp Act Fails

The 1765 Stamp Act proved an abysmal failure. Mobs ultimately forced all the stamp distributors to resign. Not one of the thirteen colonies collected a shilling from the tax, and the boycott worsened England’s already-depressed economy. The act was repealed within a year. When news of the repeal reached Philadelphia on May 19, 1766, large crowds drank to the health of King George III (1738-1820).

In May 1767, the British Parliament again tried to tax the American colonies, prompting a second round of protests and nonimportation agreements. Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend (1725-67) proposed duties to exploit what he perceived to be an apparent flaw in the Patriots’ argument. While the Patriots denied Parliament’s right to tax, they acknowledged Parliament’s right to regulate colonial trade. Accordingly, the Townshend Acts placed import duties on five categories of imported items: paper, glass, paint, lead, and tea.

While response to the Stamp Act had been immediate and spontaneous, resistance to the Townshend Duties was not. Philadelphia’s merchant community remained divided, both because many of the wealthier merchants wished to try to obtain repeal of the duties quietly, through their contacts with English merchant houses, and also because merchants trading primarily in manufactured British goods (“dry goods” merchants) stood to be much more heavily affected by the terms of the boycott than those houses trading primarily with the West Indies, in “wet goods.”

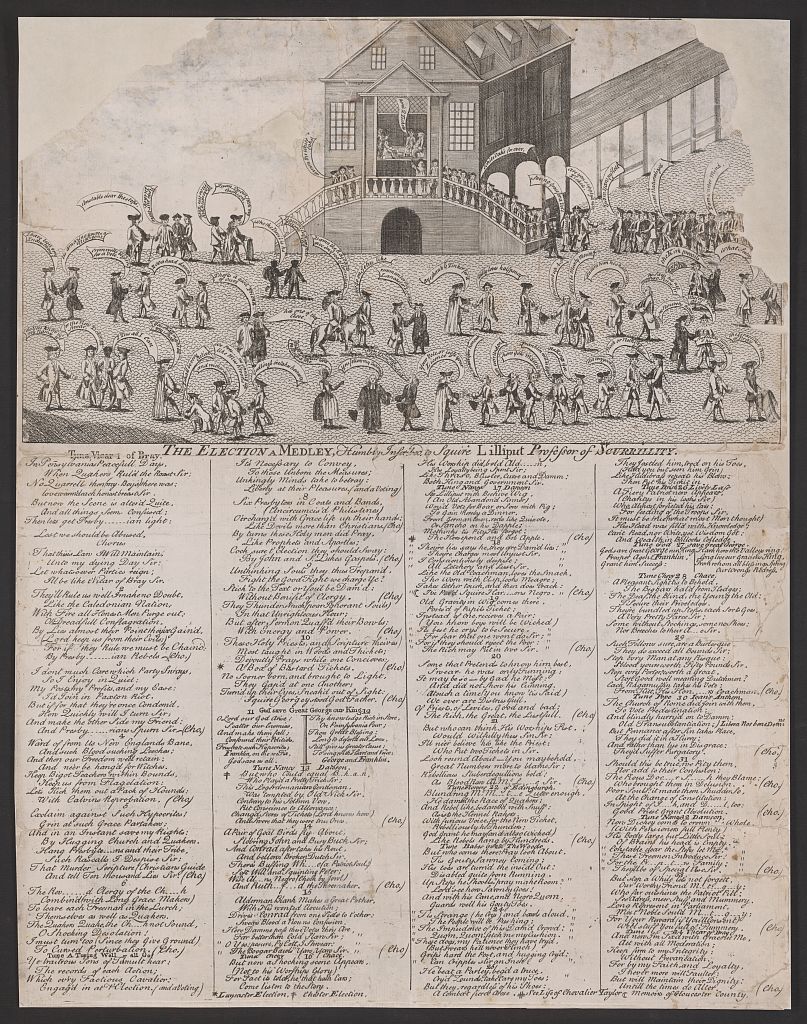

As segments of the Philadelphia merchants’ community resisted calls for an intercolonial nonimportation agreement, political power in Philadelphia began to shift to the mechanic and artisan community, who were more heavily in favor of the ban. By the summer of 1770, Philadelphia radicals, working with the artisans and mechanics, were a new force in Philadelphia politics. Nonimportation appealed to Philadelphia mechanics from the start, as they also had economic motive to support the boycott, which reduced competition from imported British manufactured goods and hence aided domestic manufactures.

“Letters From a Farmer”

The protest movement also found a powerful advocate in John Dickinson (1732-1808), a Philadelphia lawyer connected to Pennsylvania’s Proprietary Party. Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, which ran in the Pennsylvania Chronicle from December 1767 to February 1768, attacked the taxes on both constitutional and economic grounds. Dickinson argued that if such taxes were accepted meekly, worse would follow, endangering the very notion of private property.

By May of 1768, Boston and New York had agreed upon an intercolonial nonimportation agreement. Anti-British sentiment grew with the garrisoning of troops in Boston and the dissolving of the Massachusetts legislature. A majority of Philadelphia merchants finally adopted nonimportation on March 10, 1769. However, Patriot enforcement methods (including threats of violence to persons or establishments) alienated many of the Quaker elite, and the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting discouraged Quakers from supporting nonimportation, dividing the city’s leadership.

On April 12, 1770, Parliament repealed all of the Townshend Duties save the one on tea, which was retained to make a point about Parliament’s right to tax the colonies. By the fall of 1770, Philadelphia’s radical leaders were trying frantically to hold nonimportation together. In late September, the Philadelphia merchants ended the boycott for all products other than tea, and by December, the intercolonial boycott was defunct.

Anglo-American relations calmed somewhat in the next few years, until May 1773, when Parliament renewed the taxation controversy by passing the Tea Act. This law lowered the existing tax on tea in an effort to convince Americans to switch from smuggled foreign tea, and also granted agents of the East India Company exclusive rights to sell tea in the colonies. Patriots reacted strongly both to this perceived effort to trick Americans into paying a hidden tax and to the precedent established by granting such a monopoly to a small group of merchants. One broadside called on the “industrious and respectable Body of TRADESMEN and MECHANICS of Pennsylvania” to fight to defend the “dear-earned Fruits of our Labour” from a “Set of luxurious, abandoned and piratical Hirelings” who would ruin not only colonial merchants, but also the mechanics and artisans if such monopolistic grants spread to other items of trade.

Morality of Luxury Items

As tension over the Tea Act grew, colonial protests increasingly stressed moral arguments as well as economic ones, presenting British imported goods as dangerous luxury items that were corrupting American morals and health. One writer in Chester, Pennsylvania, noted the manifest virtue that American merchants were showing in resisting the “Pandora’s box” of danger that the tea ships represented, despite the profits that they could have made from the trade. “A Sermon on Tea,” printed in Lancaster, went so far as to depict tea as an evil in itself, blaming “the tea-table” for encouraging female gossip and malevolent rumors, extravagance, sexual promiscuity, and physical infirmities. A mass town meeting October 16 determined that anyone helping tea ships unload their goods into Philadelphia was “an enemy to his country,” and demanded the resignation of the tea consignees. Once the tea itself showed up in late November aboard the Polly, the ship’s captain was quickly persuaded by threats of fire, tar, and feathering to sail back to London without attempting to unload the cargo.

After the colonies received word of the Coercive Acts, passed by Parliament in response to the “Boston Tea Party” of December 16, 1773, nonimportation and nonconsumption agreements became truly continental. A large meeting of the “freeholders and freemen of the city and county of Philadelphia” declared the Boston Port Bill unconstitutional and resolved to support Bostonians “as suffering in the common cause of America.” Berks County, Pennsylvania, was one of many communities across America to begin collecting relief supplies to aid the people of Boston. The first Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia in September 1774 with twelve of the thirteen colonies represented, set up an association to oversee boycott of all British products. A total prohibition on imports began in December, and an export embargo was to start in September 1775 if necessary. The association called for every community to set up elected committees in order to enforce its terms, giving them sweeping authority to inspect commercial records and properties and to publicize violators. Nonimportation and nonconsumption remained major strategies for the American protest movement until the outbreak of war in April 1775 moved the quarrel to a different level.

Shannon E. Duffy received her B.A. from Emory University, her M.A. from the University of New Orleans, and her Ph.D. from the University of Maryland. She is a Senior Lecturer in Early American History at Texas State University. Her manuscript in progress, The Twin Occupations of Revolutionary Philadelphia, explores the psychological effects of the British occupation of Philadelphia under General William Howe, as well as the American reoccupation of the city eight months later under the command of General Benedict Arnold. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- John Bull and Uncle Sam: Four Centuries of British-American Relations (Library of Congress)

- Benjamin Franklin...In His Own Words: A Cause for Revolution (Library of Congress)

- The Examination of Doctor Franklin, before an August Assembly, relating to the Repeal of the Stamp-Act, &c. (Massachusetts Historical Society)

- The American Revolution, 1765-1783 (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Road to Revolution, 1763-1776 Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)

National History Day Resources

- Stamp Act announcement and description [Pennsylvania Gazette], March 4, 1765 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Benjamin Franklin letter to John Ross, 1765 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Resolution of Non-Importation Made by the Citizens of Philadelphia, 1765 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania: To the Inhabitants of the British Colonies (Dickinson College)

- Broadside: To the Tradesmen, Mechanics, &c. Of the Province of Pennsylvania, December 4, 1773 (CUNY)

- Joseph Galloway’s Speech to the Continental Congress, September 28, 1774 (Library of Congress)

- Joseph Galloway’s Plan of Union, September 28, 1774 (University of Chicago)

- Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1789: Selected Documents (Avalon Project, Yale Law School)

- New Jersey in the American Revolution, 1763-1783: A Documentary History (New Jersey State Library)

- The Sentiments of an American Woman broadside, 1780 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)