Settlement Houses

Essay

The settlement house movement, a phenomenon of the Progressive era with origins in London, spread to Philadelphia in the 1890s as a large influx of needy immigrants and unsanitary conditions in the city attracted the attention of middle-class, college-educated reformers. Living among the poor in South Philadelphia, Kensington, and other neighborhoods, settlement house residents sought to improve area living conditions. In the process, they also created new roles for women in a changing society.

The settlement house movement began in London in 1884 when Samuel Barnett (1844-1913) and his wife, Henrietta Barnett (1851-1936) opened Toynbee Hall “to live as neighbors of the working poor.” The volunteers who settled in the neighborhood and lived in the settlement house differentiated the movement from a mission or a school. Stanton Coit (1857-1944) brought the movement to the United States in 1886 by opening Neighborhood Guild (later called University Settlement) in New York City’s Lower East Side. The second American settlement, also located in New York City, was the College Settlements Association’s Rivington Street House, which opened in October 1889. Two weeks later, Jane Addams (1860-1935) and Ellen Gates Starr (1859-1940) established the nation’s third and most well-known settlement, Hull-House in Chicago. These were the first of hundreds of social settlements established in the United States during the Progressive era.

Settlement residents were typically middle-class college graduates. Many were inspired by the social gospel movement, which emphasized Christian responsibility for addressing urban problems. The headworker was salaried; other residents paid room and board. Men participated in the movement, but women comprised the majority of settlement workers. Female settlement residents were “new women” who revolted against the prevailing values of domesticity by gaining independence outside the family and finding personal satisfaction through “municipal housekeeping”—improving conditions outside the home.

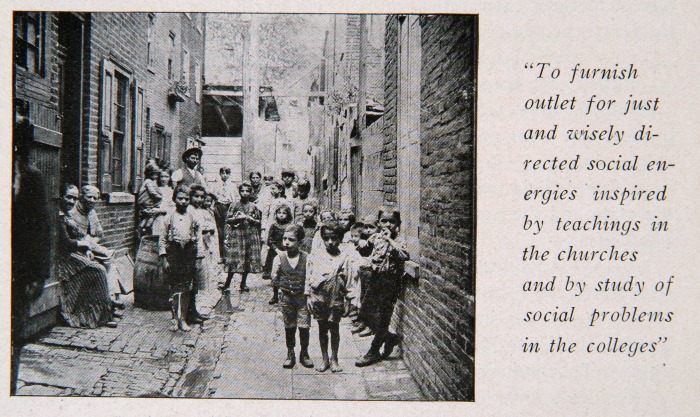

Between 1870 and 1920, a period of high immigration, Philadelphia’s population doubled. Many newcomers lived in crowded, unventilated row homes where toxic smells and putrid streets were inescapable. Open drains with raw sewage seeped from back alleys into the streets. Flies and mosquitoes, along with the horse manure festering in the cobble-stoned streets, were summer health hazards. Responding to those conditions, the first settlement house in Philadelphia, opening in April 1892, was the St. Mary Street College Settlement, which changed its name in October 1893 to the College Settlement of Philadelphia. Motivated by the housing reform efforts of the Octavia Hill Association, members of the St. Mary Street Library Executive Committee (Hannah Fox, Helen Parrish, Susan Wharton, and others) contacted Vida Dutton Scudder (1861-1954), the Smith College graduate and Wellesley English professor who was the main impetus behind the College Settlements Association (CSA). They offered the house at 617 St. Mary Street and agreed to co-sponsor a settlement with the CSA. In addition to New York and Philadelphia, the CSA established settlements in Boston (1892), and Baltimore (1910). As the first settlement in Philadelphia, the College Settlement became known as “the Settlement.”

Graduate-Level Courses

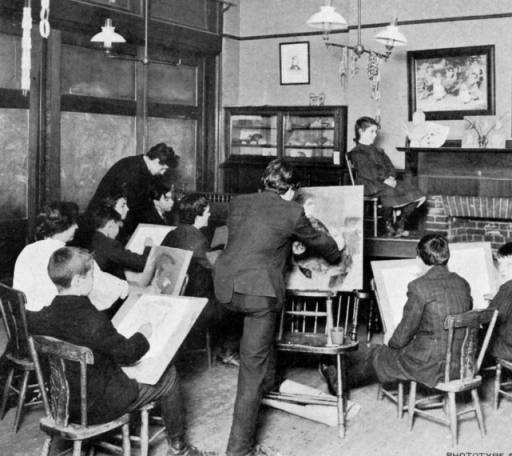

Scudder intended that CSA houses would enable women college graduates to apply the knowledge learned in economics and sociology classes while interacting with the urban poor. Consequently, the Settlement offered graduate-level courses in economics and sociology and and training in social work prior to the 1898 opening of the New York Summer School of Philanthropic Work, the first recognized school for social work education in the United States.

Located in one of the oldest and most destitute African American neighborhoods in Philadelphia, the Settlement was established exclusively to aid African Americans. In 1896, the Settlement, encouraged by Susan P. Wharton (1852-1928), collaborated with the University of Pennsylvania to sponsor sociological studies of African Americans in the Seventh Ward by W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) and Isabel Eaton. Arriving in August 1896, Du Bois and his wife Nina lived in the Settlement’s kitchen and coffee house/library building at 701 Lombard Street for one year while he conducted his research.

When the city demolished all of the houses on the 600 block of Rodman Street (formerly St. Mary Street) in 1899 to expand Starr Garden Playground, the Settlement was forced to move. Instead of moving west across Broad Street and remaining with African Americans, it moved east to 431 and 433 Christian Street because Scudder and the CSA encouraged relocating to a more ethnically-diverse neighborhood. The Settlement’s “Visiting Nurse Report for October 1899 to October 1900” indicated the diversity of the new neighborhood. Of the 489 patients, 216 were native-born Americans, 105 Italians, 70 Russians, 57 Germans, 19 African-Americans, 9 Irish, 7 Polish, 2 Hungarians, and one from each of the following: England, France, Scotland, and Wales.

Opposed to the move to Christian Street because of her life-long dedication to African Americans, Susan Wharton resigned from the Settlement opened Starr Centre at what had been the Settlement’s kitchen/library building at Seventh and Lombard. She later opened Whittier Centre for Blacks in North Philadelphia. Renamed the Susan Parrish Wharton Settlement after her death in 1928, the Settlement continued in the twenty-first century as the Wharton Centre at 1708-10 N. Twenty-Second Street.

Americanization Efforts

By 1911, Philadelphia had twenty-one settlements. Most were in South Philadelphia, but others opened in other neighborhoods, including two in Kensington: The Lighthouse, founded in 1893 at 153 W. Lehigh Avenue, and the Lutheran Settlement House founded in 1902 at 1340 Frankford Avenue. In addition to collaborating to alleviate squalid living conditions among the poor, the settlements supplemented public-school Americanization efforts with programs in citizenship, civics, and hygiene. Classes for adults included literacy, cooking, child care, nutrition, housekeeping, and carpentry. Settlement workers also volunteered aid during the influenza epidemic of 1918-19.

The settlement movement declined after World War I as more career and employment opportunities opened to women college graduates, and settlement houses that continued to operate abolished the residency requirement. Social work became professionalized, and settlements achieved many of the reforms they had worked for, such as kindergartens, playgrounds, truant officers, juvenile courts, visiting nurses, maternity and child care, and street cleaning and paving.

In Philadelphia, The Lighthouse and the Lutheran Settlement were among those that continued into the early twenty-first century as community-based agencies. The Lutheran Settlement opened Jane Addams Place for homeless mothers and their children in 2006. Another remnant of the settlement house movement is the Settlement Music School, founded in 1908 when members of the Philadelphia Orchestra offered to provide lessons for College Settlement children. Expanding to include all interested applicants, the Settlement Music School provided instruction for thousands of Delaware Valley children. In 2013, there were branches in Philadelphia, Willow Grove, and Camden, New Jersey. The College Settlement’s Farm Camp in Horsham, Montgomery County, directed by Frank Gerome, continued to provide children time away from the city on land that was purchased in 1939 by Anna Freeman Davies, the College Settlement’s headworker from 1899 to 1942.

The Federation of Neighborhood Centers, which dates back to the Philadelphia Settlement and Missions Workers Union in 1906, also continued the legacy of the settlement movement. In 2013, in addition to The Lighthouse and the Lutheran Settlement, the Federation’s members included Diversified Community Services, Friends Neighborhood Guild, Grace United Methodist Church, Legacy Christian Academy, Methodist Services for Children and Families, North Light Community Center, Tomorrow’s Promise, United Communities of Southeast Philadelphia, and the Village of Arts and Humanities. The number of religious-sponsored organizations involved in providing social services continues the intertwining of social gospel and reform that motivated the social settlements of the nineteenth century.

Rosina McAvoy Ryan teaches in the Department of History at La Salle University. She earned her Ph.D. at Temple University, where her dissertation examined the College Settlement of Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University