Streetcars

By John Hepp | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

For more than 150 years streetcars have served the Philadelphia area and helped Center City Philadelphia retain its commercial, retail, and entertainment supremacy in an ever-expanding region. Although the motive power switched from horses to electricity (with short detours into steam and cable), most change has been evolutionary rather than revolutionary. Perhaps the greatest transformation took place in the early twentieth century when the combination of rising working-class wages and regulated fares allowed streetcars, once a middle-class means of transport, to become a key component of a truly heterogeneous mass transit system. Because of the streetcars’ importance to urban life, twice they played key roles in the civil rights movement in Philadelphia.

The first streetcars in the region, running on steel rails and pulled by horses, began operating on the Frankford and Southwark Philadelphia City Passenger Railway Company on January 20, 1858. Quickly the routes pioneered by the first form of on-street public transportation, the omnibus, became street railways. The steel rails made for a smoother and a faster journey for passengers. The result for the operators was an expanded range, and fewer horses and cars were needed to maintain the level of service that the omnibus had provided.

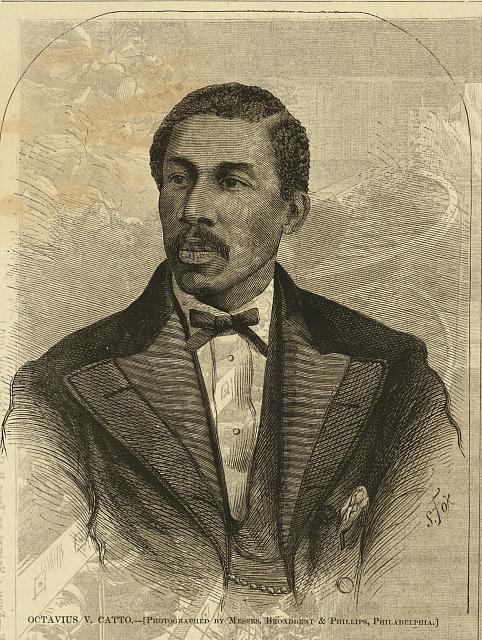

By the early 1860s, streetcars had replaced omnibuses throughout the city. Streetcar fares were lower than those charged by the omnibuses but still remained high enough that most regular riders were middle class or above. Although streetcars were credited with allowing middle-class women to travel freely throughout the city, there were two notable restrictions on patronage in the early years: Blacks were not permitted to ride on the cars and there was no Sunday service. Between 1859 and 1867, after African Americans protested the racial restriction on ridership, a few lines allowed Black passengers (some on segregated cars). Although white passengers in the city voted to continue the racial restrictions, civil rights activists William Still (1821-1902) and Octavius Catto (1839-1871) moved the debate to Harrisburg and Pennsylvania opened the streetcars to all in March 1867. Also that year, Philadelphia became the last city in the country to institute Sunday streetcar service.

The City Expands

Expansion of Philadelphia’s streetcar network allowed middle-class families to move to new residential areas like West Philadelphia east of Fortieth Street and lower North Philadelphia. These developments in areas annexed to the city by the Consolidation of 1854 became the region’s first streetcar “suburbs.”

Streetcar service also expanded throughout the region in the 1850s and 1860s. The rails allowed the streetcars to operate in areas where poorly paved or unpaved streets had prevented omnibus service. Trenton, Camden, and Atlantic City in New Jersey had streetcars, as did Norristown and Darby in Pennsylvania.

By the Centennial year of 1876, Philadelphia could claim the largest street railway system in the country. Although true, this claim was also a result of the city’s many narrow, one-way streets that meant that many streetcars traveled out of the city on one street, then returned on another, thus doubling the length of track in use. But all was not well on the system despite an annual ridership of over 100 million passengers. In 1872 the Great Epizootic, a fast-moving equine flu, affected most horses throughout the nation. Although many horses recovered, the outbreak caused streetcar operators to consider other means of power. Operators first tried steam engines on the street railways in 1876 and 1877-8, but these were unsuccessful and unpopular.

In 1883 a trio of entrepreneurs, William Kemble (1828-1891), Peter A. B. Widener (1834-1915), and William Lukens Elkins (1832-1903), formed the Philadelphia Traction Company to acquire existing streetcar lines and convert them to cable operation. The higher costs of the cable car infrastructure started the consolidation of the various routes into larger concerns despite restrictions on mergers and cross-ownership (usually avoided by the use of long-term leases and holding companies).

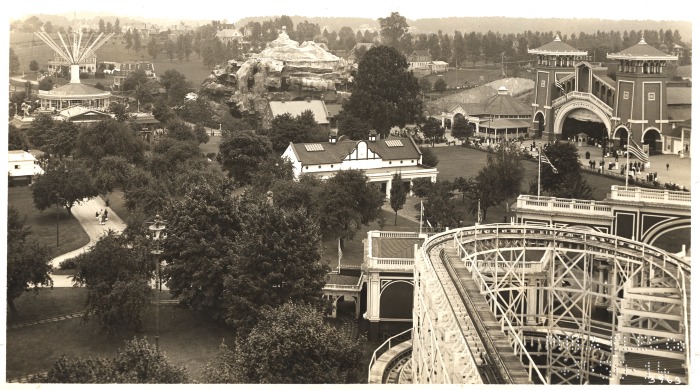

By the mid-1880s, however, the electric trolley was invented and it was clearly the technology of the future. Unfortunately Philadelphia Traction’s investment in cable cars and the small size of most other companies contributed to Philadelphia’s slow adoption of trolleys (as did safety and aesthetic concerns among the public). Following the conservative Kemble’s death in 1891, Widener decided to abandon cable operation for electrification. The first electric line on Bainbridge and Catharine streets opened in 1892, and the horse cars made their final runs in Philadelphia just five years later. In 1895 Widener and Elkins formed the Union Traction Company and within three years it controlled nearly all the lines in the city. To help increase off-peak ridership, the company built a large amusement park at Willow Grove in the northern suburbs in 1896. One of the region’s other successful amusement parks, Woodside in Fairmount Park, was owned by the Fairmount Park Transportation Company, which operated a popular trolley line through the park from 1897 to 1946.

Beyond City Limits

Starting in the 1890s and continuing for the first two decades of the twentieth century trolleys expanded throughout Philadelphia’s suburbs. Initially from Sixty-third Street in West Philadelphia (and after 1907 from the Sixty-ninth Street Terminal in Upper Darby), routes of the Philadelphia & West Chester Traction (later known as “Red Arrow Lines”) went to West Chester (1899), Ardmore (1902), Media (1913), and Sharon Hill (1917). In Norristown routes from Berks County and the Lehigh Valley met lines from Philadelphia. Southern New Jersey developed its own intricate systems centered on Camden and Trenton.

The expansion of the lines, combined with the construction of the Market Street Subway-Elevated through West Philadelphia, allowed for “streetcar suburbs” to become commonplace throughout the region. In the city itself, middle-class development moved steadily in virtually all directions from the core. The Red Arrow Lines allowed for the development of much of Delaware County, and other trolley lines opened up portions of eastern Montgomery and southern Bucks counties in Pennsylvania. In Camden County, New Jersey, the Public Service Railway owned the bulk of the network that allowed for the development of suburbs like Collingswood and Haddonfield.

In order to build the Market Street Subway-Elevated, the Widener-Elkins interests formed the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company (PRT) to take over Union Traction in 1902 and this new corporation and its financial structure would adversely affect the streetcars. The PRT struggled because of its huge debts and large annual lease payments and, in 1911, following two violent strikes, Thomas Eugene Mitten (1864-1929) (with the backing of the banking firm of Drexel, Morgan) took over the company. Mitten began to purchase new cars (known as the “Nearside Cars”), modernize the system, and improve both employee and passenger relations. From 1920 onward, however, expansion of the PRT’s trolley lines effectively came to a halt as the company switched to using buses and trackless trolleys on new routes.

Although suburban trolley service began to contract in the 1930s as lines closed and were replaced by buses, the PRT system in the city remained largely intact (as did the Red Arrow system in Delaware County). Following Mitten’s death in 1929, the PRT struggled again and declared bankruptcy in 1934. Near the end of its existence, the PRT in 1938 placed in service a small number of modern, streamlined streetcars: the PCCs. In 1940 the PRT reorganized as the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) under the control of Albert M. Greenfield (1887-1967), a real estate developer and civic leader, and continued to order PCC cars.

Wildcat Strike

On August 1, 1944, a wildcat strike took place on the PTC to protest the hiring of African Americans in skilled positions (such as motormen and conductors). The protest, the largest U.S. labor action during World War II, lasted for a week and adversely affected war production. The NAACP moved to end the strike quickly and worked with many community organizations to ensure equal treatment and moderate violence. Because of the strike’s impact on war production, President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) authorized the Army to take control of the transit system and 5,000 heavily armed soldiers were sent to Philadelphia to end the strike.

After the end of WWII, the PTC bought more PCC cars to modernize its existing streetcar system. In 1955, National City Lines (owned by General Motors and oil and rubber companies) acquired control of the PTC and quickly replaced twenty-four trolley routes with buses and abandoned over two hundred miles of track.

Despite National City Lines’ efforts, Philadelphia retained a large network of trolleys through the 1970s. In 1968 the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) acquired the PTC and initially no changes took place in the existing streetcar network. However, in 1975 a fire at the Woodland car barn destroyed approximately sixty of the PCC cars and SEPTA began to abandon trolley routes again. Following the purchase of new streetcars for the subway-surface lines in West Philadelphia in the early 1980s, SEPTA retired its PCC cars and abandoned all remaining surface streetcars by 1992. In 2005, SEPTA rebuilt a small fleet of PCC cars and reintroduced streetcar service on the Route 15 between Port Richmond and West Philadelphia via the Philadelphia Zoo.

In the suburbs, very few streetcars lines survived the Great Depression. The notable exception was the Red Arrow system radiating from Sixty-ninth Street Terminal. Although buses replaced the trolleys to West Chester in 1954 and Ardmore in 1966, the two remaining routes (to Media and Sharon Hill) are today still operated by SEPTA, which acquired Red Arrow in 1970. Starting in 1981, SEPTA reequipped both lines with a fleet of trolleys similar to the cars used on the subway-surface lines in the city.

John Hepp is associate professor of history and co-chair of the Division of Global History and Languages at Wilkes University in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where he teaches American urban and cultural history with an emphasis on the period 1800 to 1940. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History