Working Men’s Party

Essay

The Working Men’s Party of Philadelphia emerged in 1828 out of discontent with societal and workplace changes since the turn of the century. It formed out of the workingmen’s movement of the late 1820s and sought broad reforms. Although short-lived, the effort contributed significantly to injecting politics with working-class issues, many of which became prominent in the city and state over the next decade.

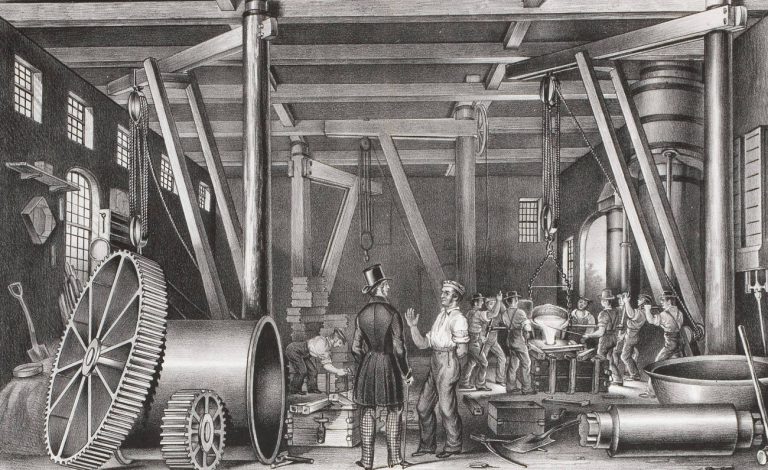

In the first two decades of the nineteenth century, workers struggled to maintain a living wage as master artisans and entrepreneurs, seeking to expand production to meet the demands of expanded markets, instituted division of labor and lowered wages. Even as the twelve-hour day, or longer, became standard, workers faced the specter of imprisonment for debt, which in many cases occurred over trivial amounts of money. Workers also bridled at an education system that consisted of private and charity schools, which offered only limited opportunities for their children. Politically, Philadelphia also proved to be unfavorable for workers, as an 1806 Cordwainer’s Trial judgment prohibited them from organizing for higher wages and few politicians proved to be advocates for the workingman.

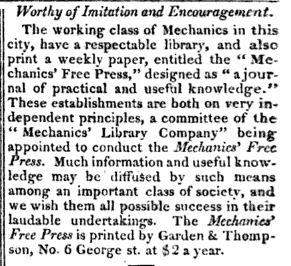

As discontent grew into the late 1820s, workers drew on Revolutionary era ideals to argue that increased disparities of wealth and power contradicted the nation’s founding principles. Opposition initially centered on the extended hours of the workday, which workers contended not only damaged their health, but hindered their ability to properly educate themselves on issues they had a right to vote on. Citing those concerns, carpenters went on strike for a ten-hour day in the summer of 1827. When the strike proved unsuccessful, labor leader William Heighton (1800-73) rallied journeymen to form the Mechanics’ Union of Trade Associations (MUTA), the nation’s first citywide coalition of local unions.

Recognizing how trades unions and journeymen societies had failed to secure working-class interests, Heighton turned to politics. At a January 1828 meeting of MUTA, Heighton presented a resolution for the creation of the Working Men’s Party. Officially formed on August 11 as the nation’s first labor party, the party platform called for a ten-hour workday, free public education, abolition of imprisonment for debt and the use of prison labor, militia reform, the creation of a mechanic’s lien law, a cheaper legal system, and a more equitable tax system.

During the 1828 election, Working Men’s candidates appeared on both city and county ballots for positions on the city councils and state legislature. A majority of these candidates ran on joint tickets with both the National Republican and Democratic parties. Only those joint-ticket, labor-endorsed candidates won, as the eight candidates who ran solely on the Working Men’s Party ticket were defeated. Heighton attributed this poor showing to the complications of nascent political movements and hoped for a better outcome in 1829. However, despite its limited impact at the polls, the party could take some solace in that both major parties printed election bills with the words “From Six to Six,” the slogan for the ten-hour workday (including one hour off for lunch and one for dinner). Issues important to the working class had become part of the political discussion in Philadelphia.

Following the 1828 election, party ward and district clubs formed in hopes of gaining further support. Organizers in Southwark formed the first men’s political club, the Working Men’s Republican Political Association, in January 1829. To demonstrate the party’s independence and attempt to prevent fusion with the other parties, Working Men candidates were chosen by city and county conventions before the other parties held their conventions. That year the Working Men’s Party reached the highest point in its existence with the election of twenty of its fifty-four candidates, including those for sheriff and county commissioner. Although all of the successful candidates ran on joint tickets, their success gave labor-endorsed candidates the balance of power in Philadelphia.

Success proved temporary, however, as the Working Men’s Party quickly lost traction. Democrats, who claimed sole interest in the workingmen, acted to split the Working Men’s Party into factions. As the election of 1830 approached, members of the organization fiercely debated whether their candidates for the fall election should be workingmen, or “tried friends” of the movement, such as former banker and newspaper editor Stephen Simpson (1789-1854). As internal discord increased, both the National Republican and Democratic parties took aim at their constituents by adopting items from their platform, such as free public schools, abolishment of imprisonment for debt, and support for the ten-hour movement. Increasingly members of the Working Men’s Party threw their support to the more established and better funded parties.

Stung by the party’s poor performance in 1830, Heighton blamed the apathy of his fellow workers, and he left the city for good. In 1831 the Working Men’s Party failed to offer a single candidate for election. America’s first labor party was dead. However, the issues raised by the party lived on and the movement that started in 1827 began to achieve results in the 1830s. In 1833 Pennsylvania abolished imprisonment for debt. The following year the state passed the Free School Act of 1834, which offered primary education to every child without the necessity of publicly declaring their poor financial status. In 1835 the Philadelphia Common Council announced that workers employed by the city would be granted a ten-hour day.

The Working Men’s movement of Philadelphia was more than simply an attempt by workers to gain better wages and hours. Infused with the ideals of economic, social, and political equality, its causes spread throughout the Northeast to cities such New York and Boston with the introduction of free public schools, the end of imprisonment for debt, and the fight for a shorter week.

Patrick Grubbs is a Ph.D. candidate at Lehigh University who is writing his dissertation entitled “The Duty of the State: Policing the State of Pennsylvania from the Coal and Iron Police to the Establishment of the Pennsylvania State Police Force, 1866 – 1905.” He has been employed at Northampton Community College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, since 2009 and has taught Pennsylvania history there since 2011. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History