Arts of Wharton Esherick

Essay

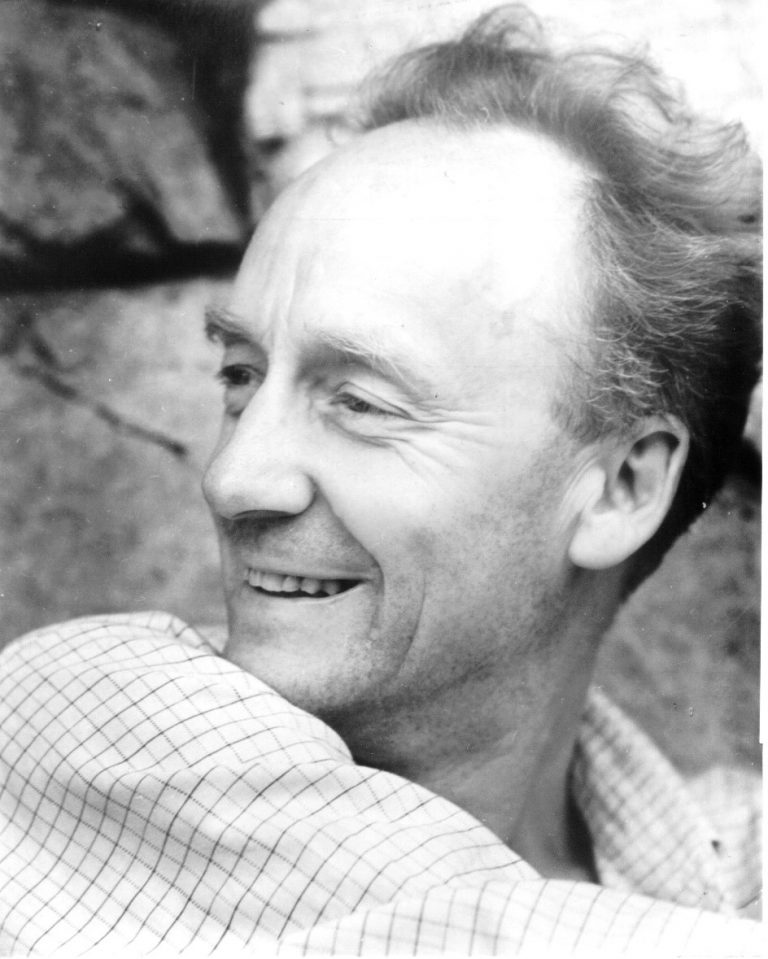

The unconventional artistic trajectory and prolific work of prominent Philadelphia-area artist and craftsman Wharton Esherick (1877–1970) have been claimed for and by multiple movements in the history of twentieth-century American art, from early-twentieth-century Arts and Crafts to postwar studio craft. Working across a wide variety of media, including printmaking, sculpture, furniture, and theatrical design, Esherick also attained fame for the studio he built over several decades in Paoli, Pennsylvania, which became a draw for other creative figures from Greater Philadelphia and farther afield. Directly shaped by him over the course of decades, the building and its site became an extension of his integrative approach to the arts.

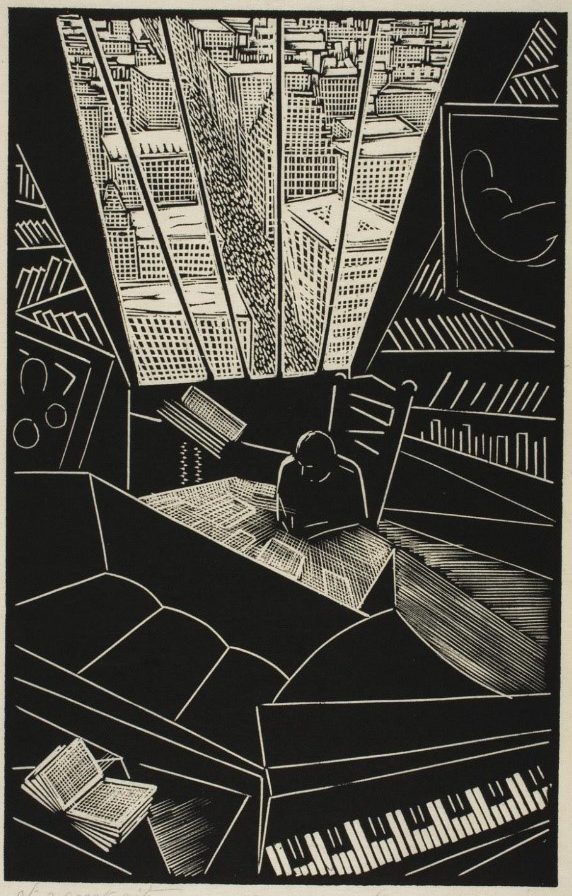

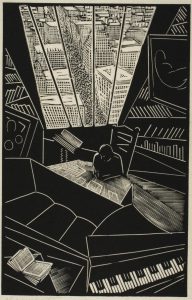

Born to a well-to-do West Philadelphia family, Esherick attended the Central Manual Training High School and trained in printmaking and commercial art at the Pennsylvania Museum School of the Industrial Arts (later University of the Arts). In 1908 he received a scholarship to study painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he worked under some of the leading Pennsylvania Impressionist painters of the day. However, apparently dissatisfied with academic constraints, he left the academy before completing his studies and began working as a commercial artist and book illustrator while attempting to sell paintings. In 1913, he moved with his new wife Leticia (“Letty,” 1892–1975) to a small farm in Paoli that they called Sunekrest (pronounced “sunny crest”), drawn by an idealized notion of rural life that would allow him to develop as an artist. Although Esherick struggled to find an audience for his paintings, the wood frames he began carving for them drew praise, and from the early 1920s he increasingly worked as a sculptor in wood, as well as a printmaker and maker of functional objects. His prints and sculptural work in particular exhibited the smooth contours and semi-abstraction that characterized the growing modernist art movement in the United States.

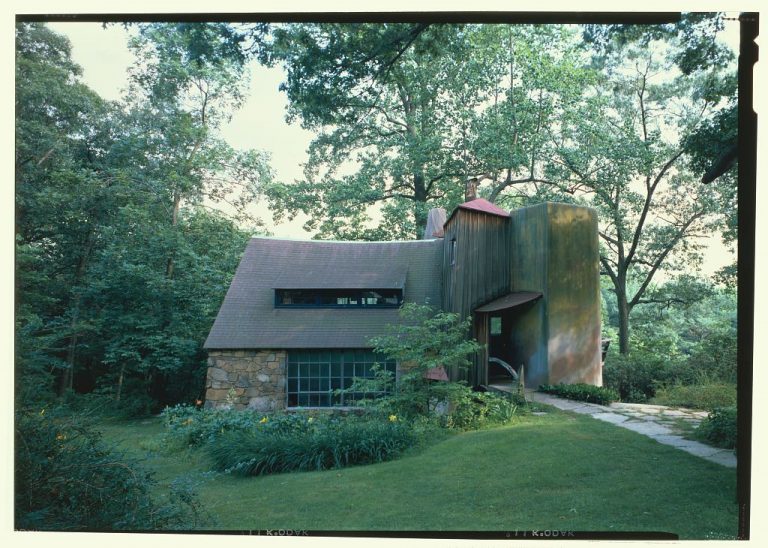

In 1926, he began building a barnlike studio on his land, somewhat removed from the farmhouse he shared with Letty and their children Mary (1917–96), Ruth (1923–2015), and Peter (1926–2013). Esherick modeled his studio after the region’s historic barns, constructing thick stone walls with the help of a local stonemason and intentionally introducing curves to the architecture in a suggestion of timelessness. Esherick’s conscious evocation of vernacular barn architecture was influenced by Expressionist tradition and certainly by Greater Philadelphia’s rural Arts and Crafts art colonies (like nearby Rose Valley), with their attempts to integrate the visual, applied, and performing arts into a utopian vision of “honest” labor and social cohesion.

Esherick had an even more direct connection to Rose Valley through his involvement in the Hedgerow Theater, established in 1923 in the colony’s former mill building after the Rose Valley Association and its workshops had disbanded in 1910. He designed and built furniture, stage sets, and interior fittings for the theater and made prints to promote performances. He even displayed his sculpture works there, using the theater as a kind of informal gallery. Esherick maintained close connections to the performing and literary arts throughout his career. He developed friendships with many of the authors, playwrights, dramaturges, and educators who worked with the Hedgerow Theater; those he met in New York City or during his family’s summer travels to dance camps; and the circle of Philadelphia’s Centaur Book Shop and Press, whose focus on small-edition fine book printing appeal to Esherick’s sense of workmanship. He would also occasionally host literary and theatrical guests at his home and studio, which acted as a kind of crossroads between art forms.

Although furniture would become his best-known work, it was initially a somewhat tangential endeavor for Esherick, who early on designed and built pieces as need arose or for special favors to friends. His early designs were heavily built and vaguely inspired by medieval forms, clearly expressing the joinery and carving techniques that went into their making. Some prominent furniture and interior commissions in the Philadelphia area, New York City, and elsewhere in the late 1920s and into the 1930s brought Esherick increasing attention as a designer. Many of his inventive asymmetric furniture forms—called “prismatic” or later even “Cubist” by commentators—showed an attention to the growing popularity of Art Deco, while his commitment to a high level of craftsmanship brought his functional work increasing acclaim. His growing success was all the more notable for the relative lack of a robust professional network for fine woodworking (academic programs, professional organizations, publications, and galleries) at the time.

Esherick’s largest commission in both physical and financial terms began in 1935 for the judge Curtis Bok (1897–1962; son of the Philadelphia publisher Edward Bok [1863–1930]) and took three years to complete. He provided stylistically inventive architectural elements and furniture for a suite of rooms including a library, a dining room, a music room, as well as a dramatic spiral staircase for the house’s entry hall. By the late 1930s, he was creating slender, organic furniture forms that became his signature in the latter part of his career, which lasted well into the postwar decades. A key vehicle of his success was the inclusion of some of this furniture—along with the dynamically cantilevered spiral stair he had added to his studio in 1930—in the “Pennsylvania Hill House” display at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, designed in collaboration with Philadelphia architect George Howe (1886–1955). Esherick also continued expanding the studio building, adding a kitchen and living quarters as he spent ever more time on his work, especially after separating from Letty in 1937.

After Esherick’s death in 1970, his children and heirs incorporated the nonprofit Wharton Esherick Museum, preserving the studio building and its contents almost entirely intact. Open to the public since 1972, Esherick’s former studio tells the story of his practice through the preservation and interpretation of his living and working environment. Individual works by Esherick have been acquired by public collections around the United States—as have some of the interiors from the Bok House, salvaged before its demolition in 1989—but the Wharton Esherick Museum’s establishment created an institution uniquely placed to conserve and study Esherick’s varied artistic career and its lasting impact on Greater Philadelphia’s cultures of making. While commentators and historians have described him variously as an inheritor of the Arts and Crafts tradition, a linchpin of interwar modernism, or a father of postwar studio craft, Esherick’s chief legacy lies in his ability to bridge these categories and their wide chronological span.

Colin Fanning is Curatorial Fellow in the Department of European Decorative Arts and Sculpture at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He holds an M.A. in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture from the Bard Graduate Center. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Works by Wharton Esherick (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

- About the Artist (Wharton Esherick Museum)

- Wharton Esherick Studio and Museum (Visit Philadelphia)

- Wharton Esherick Museum Blog

- Design, 1950-1975 (Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art)

- The United States and Canada, 1900 A.D.–present (Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art)