City Beautiful Movement

By Stephen Nepa

Essay

Grounded in landscape and European architecture and shaped by the politics of the Progressive Era, the City Beautiful Movement emerged in reaction to the physical decay and social congestion that burdened America’s industrial centers at the turn of the twentieth century. Considered the “mother” of urban planning, its promoters and practitioners sought to reorder the built environment in the cause of “civic uplift.” While expressions of City Beautiful appeared nationwide, cities in Greater Philadelphia also were shaped by the movement. From Camden and Trenton, New Jersey, to Wilmington, Delaware, and especially Philadelphia, from the late nineteenth century through the 1920s the region’s urban areas were graced with new civic spaces and associated monumental buildings designed to improve in public consciousness the very idea of the city.

In the 1880s, rising rates of immigration and industrialization brought high levels of congestion and pollution to urban areas. While early park planners brought some physical relief to city dwellers, a new generation of reformers sought further to instill a sense of pride and belonging to residents, especially immigrants with only tenuous ties to established institutions, by creating wide boulevards, ennobling buildings, and manicured parklands to allow people of all backgrounds spaces for reflection and recreation. Such inspiring spaces, they argued, could uplift city dwellers weighed down by low pay, long hours, and inadequate housing. Influenced by projects in Europe such as Vienna’s Ringstrasse, Baron Haussmann’s (1809-91) redesign of Paris, and Ildefons Cerdá’s (1815-76) work in Barcelona as well as American figures such as landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-52), Central Park creator Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903), and architect Daniel Burnham (1846-1912), dozens of examples, from museums and municipal buildings to new street grids, were proposed and completed. The movement got its initial boost from Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition. Laid out by Olmsted, Burnham, and other leading designers, the fair’s “White City,” a model (comprised of plaster of Paris) of lagoons, fountains, promenades, statues, and neoclassical buildings showcased how comprehensive planning might relieve urban problems. Subsequent fairs at Buffalo (1901), St. Louis (1904), San Francisco (1915), and Philadelphia (1926) similarly formed as grand civic spaces under the influence of the White City.

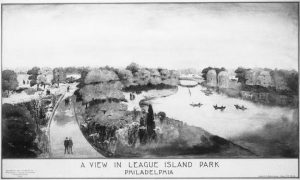

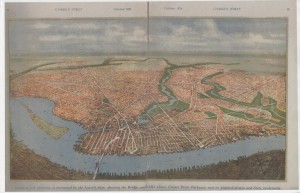

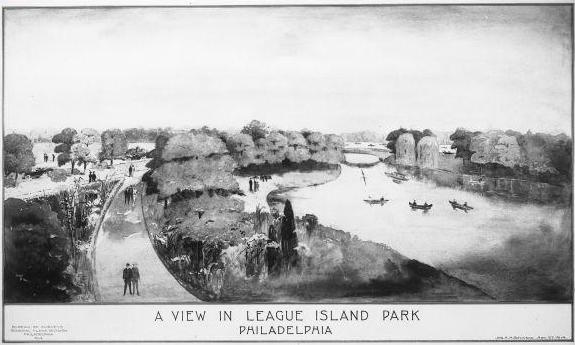

In the region, Philadelphia contained the most significant projects aligned with City Beautiful. After the Civil War, the city’s population neared seven hundred thousand and its industrial base of factories, refineries, and shipyards polluted the environment. In response, calls emerged for beautification plans and civic improvements. Emerging environmental groups including the City Parks Association, the Fairmount Park Art Association, and the women’s Garden Club of Philadelphia as well as reform-minded citizens such as Peter A.B. Widener (1834-1915) and financier Edward T. Stotesbury (1849-1938) pushed for grand Beaux-Arts architecture, boulevards in North Philadelphia, a citywide playground system, a park along the Schuylkill River’s western bank, and a new plan for South Philadelphia mimicking Washington, D.C’s planned system of radial boulevards. During WWI, local architects Albert Kelsey (1870-1950) and David K. Boyd (1872-1944) proposed the clearing of two square blocks from Chestnut Street north to Ludlow Street so as to increase the visibility of Independence Hall, one of Philadelphia’s most iconic and patriotic structures, though it was not until after WWII when their vision, known as Independence Mall, came to fruition.

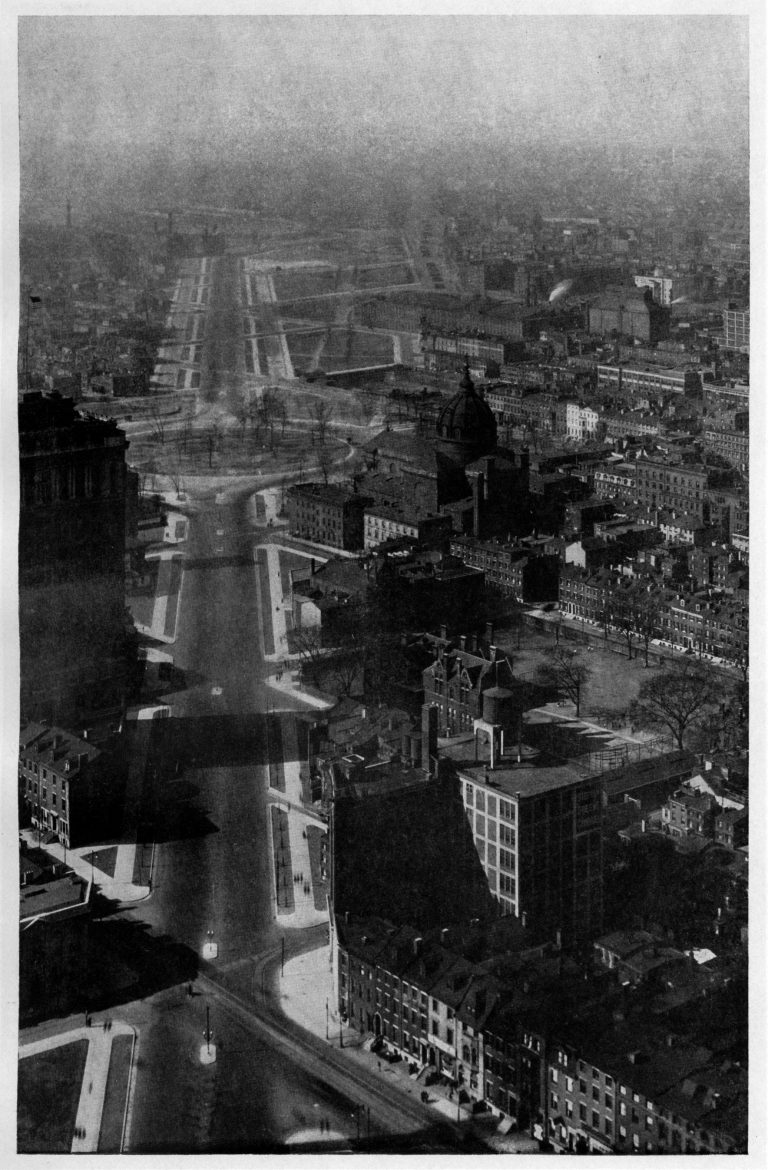

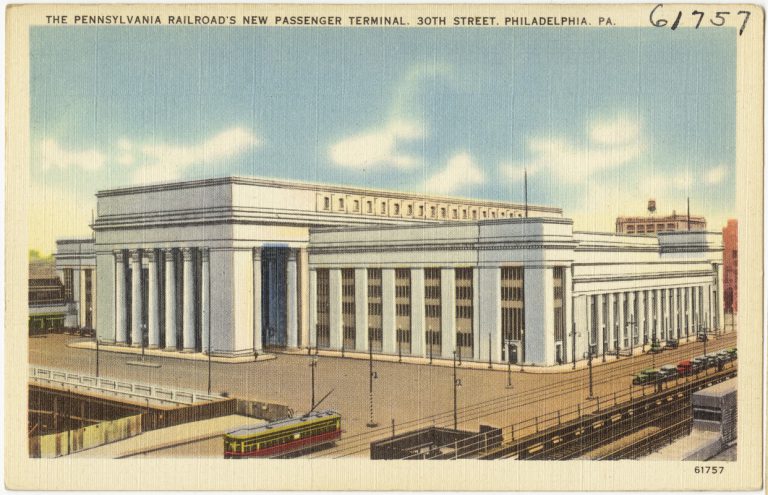

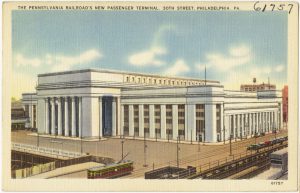

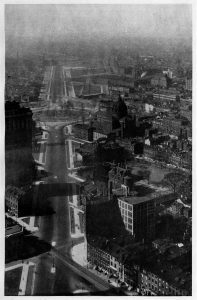

Most prominently, a number of Philadelphia’s art and civic groups championed a grand parkway to connect Center City to Fairmount Park. Based on a plan by Jacques Gréber (1882-1962) and Paul Philippe Cret (1876-1945), work on the Parisian-style project commenced in 1907. Ten years later, Gréber proposed a system of diagonal parkways radiating outward from central Philadelphia’s five squares. While this plan never fully materialized, by 1930 much of the Fairmount Parkway (renamed Benjamin Franklin Parkway in 1937), including the Free Library, Rodin Museum, the Municipal Court, Logan Circle, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art was completed or under construction. Across town, Washington Square, graced with new statuary, refurbished fountains (care of the Philadelphia Fountain Society), and two high-rises designed by Edgar Seeler (1867-1929) (the Penn Mutual and Curtis Buildings), reflected City Beautiful sensibilities. In 1933 architect Alfred P. Shaw’s (1895-1970) 30th Street Station, the city’s last “grand depot,” opened for service as a monumental gateway to the city. The Neoclassical/Art Deco station, commissioned by the Pennsylvania Railroad, replaced the company’s Gothic Broad Street Station, which was demolished in 1952.

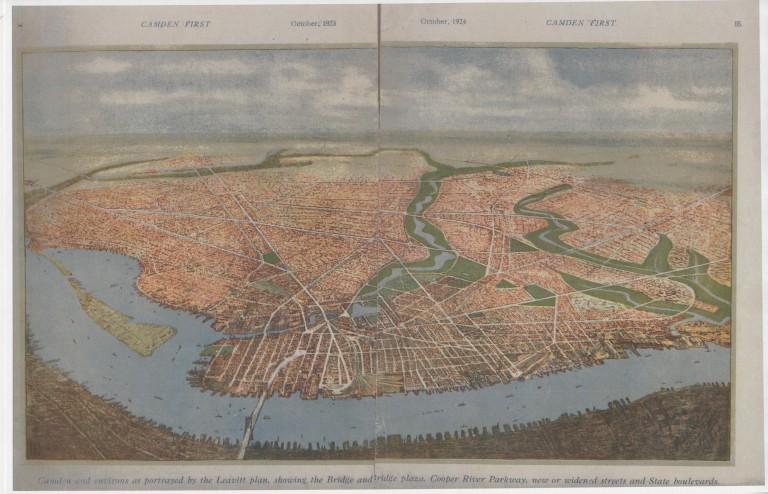

In 1913, Cret received a commission to redesign Rittenhouse Square. Influenced by Paris’ Parc Monceau, his Beaux-Arts plan for Philadelphia’s wealthiest neighborhood included diagonal walkways, new sculptures and fountains, and tree plantings. Prior to the completion of Cret’s Delaware River (renamed Benjamin Franklin) Bridge, which linked Philadelphia with Camden, New Jersey, architect Charles Wellford Leavitt (1871-1928) conceived in 1925 a system of parklands and thoroughfares to remake central Camden as the gateway to South Jersey. Echoing Gréber’s Philadelphia street plan, much of Leavitt’s blueprint was never built. Yet the city’s Admiral Wilson Boulevard, running from the bridge into the suburbs to the east, opened in 1926 and became Camden’s main traffic artery, later attracting the Sears and Roebuck Company to erect a new store in the neoclassical tradition.

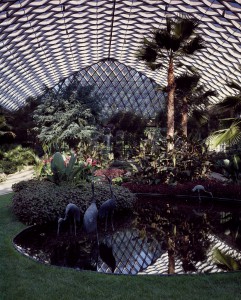

In 1888 the city of Trenton, New Jersey, began accumulating land for a grand park, a process aided considerably three years later through a donation of seven additional acres from lawyer John L. Cadwalader (1836-1914). With Olmsted as chief designer, Cadwalader Park (Trenton’s largest and Olmsted’s only one in New Jersey) included a restaurant, amusement midway, concert gazebo, and a zoological garden with lions, deer, monkeys, and black bears. Gracing the park were circular foot paths, picnic areas, ornate entryways, and statues of George Washington (1732-99) and John A. Roebling (1806-69). To offer a counterweight to urban congestion, the city submerged the Pennsylvania Railroad’s track along the park’s eastern edge. John H. Duncan (1855-1929) designed the Trenton Battle Monument, a towering Roman-Doric column graced with bas-reliefs and a surrounding plaza, which opened in 1893 and commemorating the Continental Army’s 1776 victory.

To the south, Wilmington, Delaware, also initiated projects shaped by the City Beautiful Movement. With the city growing into a mercantile and chemical manufacturing center, the DuPont Company in 1905 began construction of its new twelve-story downtown headquarters. To complement the building, in 1917 vice president Pierre S. DuPont (1870-1954), who had personally financed road improvements between Wilmington and Chester County, retained architect John Jacob Raskob (1879-1950) to redesign the one-and-a-half-acre green space across the street. Completed in 1921, the new Rodney Square included paved walkways, cast stone stairs and balustrades, and a gleaming bronze statue of Caesar Rodney (1728-84), the state’s signer of the Declaration of Independence. Further committed to the Progressive ethos of the City Beautiful, DuPont in the late 1920s opened to the public the gardens and grounds of his Longwood estate in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania.

Amidst changes brought by industrialization, population growth, and environmental concerns, the City Beautiful Movement provided for greater Philadelphia’s residents and visitors new spaces for work, recreation, and reflection. From industrial riverfronts to cramped older neighborhoods, many urban areas were demolished to promote arts and culture as well as entertainment and consumption. Yet the onset of the Great Depression in the early 1930s spelled the end of the movement as the regional economy adapted to financial collapse and high rates of unemployment. And while many local cities underwent large-scale renewal programs in the decades after World War II, nearly all of the projects shaped by the City Beautiful Movement remained intact well into the twenty-first century, attesting to their enduring importance.

Stephen Nepa teaches history at Temple University, Moore College of Art and Design, and the Pennsylvania State University-Abington. A contributor to numerous books and journals, he is currently at work on a project about the history of Puerto Rico’s Levittown community. He received his M.A. from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and his Ph.D. from Temple University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University