Courthouses (County)

Essay

The prominent locations of courthouses in the architectural landscape of Philadelphia and the surrounding region mirrored their positions as cornerstones of civic life. By the eighteenth century, courthouses with clock towers and cupolas defined city squares and communal networks. As democracy and citizenship expanded in the years that followed, pressures on the courts rose accordingly as an ever-larger body politic laid claim to justice. Meeting those demands shaped courthouse design in Philadelphia and beyond. Built in colonial, classical, and contemporary forms, over time county court buildings became larger and their interiors more specialized in response to shifts in society and the legal system.

The form of the first courthouses in the Philadelphia region came from English practice, just as the origins of the legal system grew from English common law and county-based courts. Each county had its own court, which made the county seat–where the court met– a social, economic and political hub and a significant visual reminder of the colony’s place within the British Empire. Philadelphia County and the adjacent Pennsylvania counties of Bucks, Chester, and Montgomery each had its own courthouse. After 1701, so too did the three counties of Delaware: New Castle, Kent, and Sussex. Similarly, southern New Jersey was divided into counties for governmental reasons: Burlington, Camden, Gloucester, Salem, and Cumberland, plus Atlantic and Cape May Counties on the coast, all well within Philadelphia’s city sphere.

In early Philadelphia, the city blocks closest to the Delaware River quickly became the most densely developed of the urban grid planned by Quaker and colony founder William Penn. A social and commercial center flourished near the wharves and warehouses hugging the waterline. Nearby, at Second and High (later Market) Streets, stood not only the Quaker meeting house but also the first courthouse (built in 1707, demolished 1837). The two-story, gable-roofed civic building served dual purposes, with a watchhouse on the first floor and a court on the second. Outside the courtroom was a balcony used for delivering proclamations and addresses, which added emphasis to the street façade visually and symbolically.

Amid the hustle and bustle of city streets below the balcony, urban life jostled around the deferential nature of courtroom ritual and the social hierarchy it reinforced. The legal center abutted several blocks of market stalls in a juxtaposition of street commerce and civic structure, similar to English municipal halls and markets, many of which had arcaded ground floors for the trading and social mixing. A pews-to-pulpit spatial arrangement taken from parish churches influenced the placement of judge, jury, attorney, and witness inside the courthouse, as historian Carl Lounsbury demonstrated in his analysis of both building types.

Mirroring Local Construction Traditions

County seats, particularly the first courthouses, expressed the emerging vernacular architecture vocabulary of the Delaware Valley in materials and scale. In Chester, the initial seat of Chester County, the two-story, stone courthouse (1724) mirrored local construction traditions, readily identified through stone walls, multiple-pane windows with exterior shutters, dual entries, and the pent roof associated with Quaker buildings in southeastern Pennsylvania. Inside, the courtroom occupied the first floor, and the jury rooms were on the second. In the mid-eighteenth century, an apse-like addition offered new space for the judge’s bench, furthering the correlation between church and courtroom interiors. Similarly, the brick courthouse (1732) built in New Castle, Delaware, adopted a Georgian architectural style, seen in its cupola and classical balustrade, central door with pedimented surround, and sash windows. The courthouse (1735) erected in Salem County, New Jersey, also featured brick construction and Georgian architectural details, while the wood-shingled, gable-roofed courthouse (1793) in Sussex County, Delaware, spoke to the region’s building history of wood-frame assembly. These early courthouses occupied central locations in their city plans and in civic life. When the court system outgrew them, their perceived importance to early governance and communal stature ensured the courthouses’ preservation beyond the eighteenth century, and the buildings continued to be used for occasional court activities even if county seats moved to different locations, as happened in Chester and New Castle Counties.

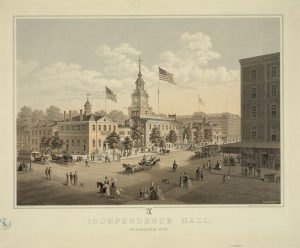

The significance of the courthouse and the courtroom’s expression of popular sovereignty and localized law resonated through Philadelphia’s colonial-era history, especially during the Revolutionary War period as a democratic government emerged. The U.S. Constitution was debated and adopted in the Pennsylvania State House (later known as Independence Hall), which had a courtroom on its first floor. When Philadelphia served as the nation’s capital in the 1790s, the nascent federal government claimed Philadelphia’s newly completed civic buildings, including a new County Court House (built 1787-89 at Sixth and Chestnut Streets), which became known as Congress Hall for its federal occupants, and City Hall (built 1790-91 at Fifth and Chestnut), which accommodated the U.S. Supreme Court and then municipal courts in the nineteenth century. Like the public buildings in Philadelphia, courthouses throughout the region fulfilled several civic needs. In Dover, Delaware, for example, the Kent County courthouse coexisted with the statehouse in a structure erected around the same time as Congress Hall. The county opened its first purpose-built court in the 1870s.

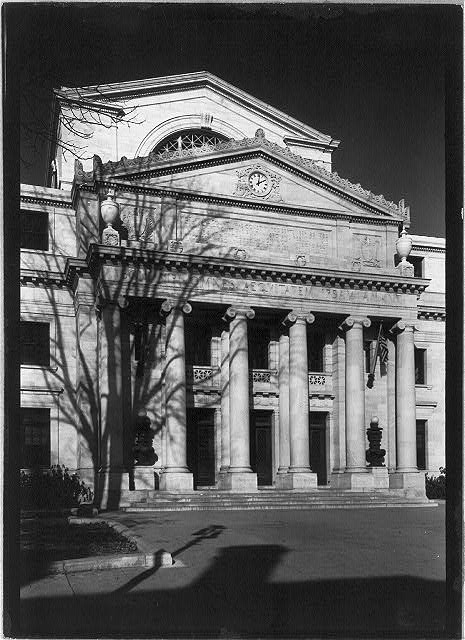

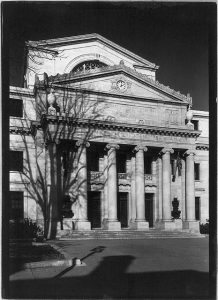

Into the nineteenth century, courthouses were among the region’s most substantial buildings in scale and building materials. Initially two or three stories, the court buildings of the new democracy were classically appointed and topped with a clock tower or, later, domes. Beneath the domes and behind monumental porticoes, traditional sash windows and wood paneled doors prevailed. As proclamations of civic pride, courthouses became plum commissions for professional architects who intended their designs to project public grandeur and protect the core of democracy: the jury trial.

The expression of democratic ideals could be seen most readily seen in classically inspired temples of justice reminiscent of ancient Greece and Rome. The association of classical architectural forms with the new democratic government informed public buildings of all types, notably the Second Bank of the United States by William Strickland (1788-1854), Girard College by Thomas U. Walter (1804-87), and county courthouses throughout the region. During the 1840s, Walter’s Chester County, Pennsylvania, courthouse in West Chester and Strickland’s courthouse in Sussex County, Delaware, helped to popularize the Greek Revival style. The two-story, red brick courthouse of Sussex replaced the county’s wood-frame building from the 1790s and kept the court functions at the heart of town. Another notable mid-nineteenth-century example was the courthouse for Montgomery County in Norristown, Pennsylvania, by Napoleon LeBrun (1821-1901).

A New Courthouse Next to Independence Hall

In the mid-nineteenth century, Philadelphia lacked an architectural temple of justice. In 1867, Philadelphia expanded its court system with a new courthouse, located behind Independence Hall, to better serve the burgeoning population and increasingly burdened legal administrators with additional space for court business: court room, jury box and deliberation rooms, judges chambers, spectators gallery, and prisoner egress. Rather than a monumental portico and classical pediment filled with sculptural iconography, the new judicial edifice echoed the Georgian architecture of Independence Hall.

Philadelphia’s mid-century courthouse provided contemporary commentary on the demographic shifts that altered views on how justice was served and made defendants less a spectacle in punishment and more a part of–and apart from–the public ritual of law and judgment. Public shaming, and subsequent shunning by neighbors and kin, gave way to imprisonment in the eighteenth century. This precipitated another building type in the county judicial centers or courthouse squares: the jail. Almost on completion, these early jails became overcrowded with prisoners who shared living space, regardless of gender or offense. Even new jails with interior and exterior spaces, such as the Walnut Street Jail (built 1790-91), failed to end the comingling or deter debauchery within the walls. These persistent social ills within the corrective institutions urged new design solutions for prisons and the fulfillment of reformist ideals for redeeming the prisoner and returning him or her to society. New prisons, like Eastern State Penitentiary built (1821-36) by John Haviland (1792-1852), were designed to rehabilitate the incarcerated through labor and solitude.

The surrounding counties also sought professional architects, such as Haviland, to expand existing courthouse squares in similar ways. For example, Burlington County, New Jersey, hired Robert Mills (1781-1855) to add a prison to its courthouse complex in Mount Holly, as early as 1808, and Atlantic County, New Jersey, commissioned Walter in the 1840s to add a jail to theirs. In Bucks County, Pennsylvania, civic leaders commissioned Quaker architect Addison Hutton (1834-1916) to design a courthouse and a jail in the 1870s, thereby crafting a cohesive architectural landscape of justice out of separate sites for the county and continuing the reformative approach to law’s administration that Haviland’s design for Eastern State Penitentiary embodied.

Also in the nineteenth century, the same demographic patterns led to the establishment of new county seats throughout the greater Philadelphia region. In two—Delaware County, Pennsylvania, and Camden County, New Jersey—the architect, and sometime partner of Hutton, Samuel Sloan (1815-54) won commissions for the new courthouse projects. The county seat of Delaware County moved from Chester, site of a courthouse with a dual-entry, Quaker aesthetic, to Media in 1850. Sloan created a temple of justice, with a classically appointed portico, to assure that Media was not to be outdone by its rival Chester County and its new courthouse in the Corinthian order by Walter of the same period.

Renaissance Revival in Camden

Sloan’s work for Delaware County was in keeping with mid-century taste for classical courthouse design throughout region, whereas his Camden courthouse (1853) revealed his leanings to the Renaissance Revival aesthetic, popular in the later decades of the nineteenth century. The building exterior was a roughcast brick and the floor levels were articulated by belt courses and arched windows; the roof rose from a deep cornice and soared upward through gabled dormers and a square tower. Sloan’s courthouse in Camden likely influenced the architectural program that emerged in neighboring Gloucester County in the 1880s.

When Camden County broke away from Gloucester in 1844, officials began to shape their municipal center. In Gloucester, however, the existing two-story, complex masonry courthouse (1787) sufficed until 1885. At that time, the historic building was demolished and the new courthouse opened. It was a Renaissance Revival design by the Philadelphia firm, Hazlehurst and Huckel. The use of masonry in the early building translated well into the weightiness of the Italian palazzo reinterpreted for the courthouse through structural ornamentation that incorporated rusticated and smooth surfaces and different colors of brick and stone. This courthouse answered Sloan’s in Camden, although neither proved large enough for the demands of the twentieth-century legal system. Camden replaced its Sloan courthouse with a domed court by 1906. Nearby Cumberland County hired the Philadelphia firm of Watson and Huckel, successor to the Hazlehurst partnership, to fashion a new court building in 1909.

Courtrooms in these classically encased courthouses had twofold enclosures: first within symbolic architectural forms, such as monumental porticos, and then within a labyrinth of specialized spaces, such as judges chambers, jury rooms, clerk offices, law libraries, administrative offices for recording paperwork. In the nineteenth century, these enclosures distanced justice from those governed—separated by columnar screens on the exterior or by the bar inside the courtroom itself—and protected their rights at the same time, as Martha McNamara chronicled in her analysis of law’s professionalization and Norman Spaulding demonstrated in his examination of legal administrative spaces.

The rituals of justice conducted in public courtrooms, therefore, reflected the accessibility of law to all citizens even as a maze of jurisprudence few navigated without counsel developed to protect that principle. The architectural choices of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, embodied these ideals in a succession of courthouses placed on the highest point in Doylestown, including the Hutton courthouse of the 1870s, and the houses facing the courthouse square that became known as “Lawyers’ Row” and that received aesthetic upgrades as tastes shifted in the nineteenth century. Hutton’s courthouse met a similar fate to its predecessors in the mid-twentieth century when county officials chose to erect a modern, two-building court and administrative center by Carroll, Grisdale and Van Alen. The courthouse building was round and the greater use of glass in the façade signified contemplation and transparency necessary in the prudent execution of justice. Ultimately the county relocated its judicial center off the courthouse square, leaving the courtroom ideal at the heart of the complex and filling the spaces with administrative offices for the business of the court.

Relocations in Philadelphia

In Philadelphia, a similar arc of expansion and debate that occurred in Bucks County over the movement of the center of justice from its traditional location took place, though condensed into the second half of the nineteenth century as plans to relocate the courts and government center from Independence Square were abandoned and City Hall on Center (Penn) Square gradually rose. The multistoried, highly ornamented Second Empire style building designed by John McArthur (1823-90) opened in 1901. The sculptural program of Alexander Milne Calder (1846-1923) added to the ornate character of the building and its enormity, with over 250 figures including blindfolded Justice with her scales. Almost immediately, the administration of justice overwhelmed even its vast interior. Philadelphia’s courts soon occupied auxiliary space in the Widener Building at Thirteenth and Chestnut Streets, and in the late 1930s, the Family Court Building at Eighteenth and Vine Streets designed by John T. Windrim (1866-1934) in the Beaux Arts tradition was added to the court system.

The interior iconography of the Family Court Building continued the decorative program of City Hall by featuring scenes in legal and local history rendered in paint, tile, and metal, as well as stained glass from D’Ascenzo Studios. In the paintings in the Family Court, justice came with a dose of paternalism to the wayward young and the newly arrived. The murals, by artists such as Stuyvesant van Veen (1910-88), encouraged a code of conduct focused on labor and deference. They hinted at alternatives to the jury trial negotiated by legal specialists and to shifts in the conveyance of justice away from the sword-bearing, blind-folded classical figure represented in porticoes and statuary through subject matter that instead featured judges pointing to role models, such as Boy Scouts, or highlighted prominent Americans.

Outside of Philadelphia, during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries annexes augmented courthouses as far as civic pride and purses could stretch. Additions to the architect-designed, mid-nineteenth-century courthouses in Pennsylvania’s Delaware and Montgomery Counties consumed full city blocks, while Bucks and Chester Counties forged courthouse clusters of old and new spaces to house their burgeoning legal systems. This was also true in Gloucester County, New Jersey, where a contemporary justice center supplemented the Hazlehurst and Huckel courthouse. In Delaware, Kent County remodeled its 1874 courthouse into a Colonial Revival-styled building around 1920 and added a three-story building around 2010. The addition evoked the arcaded first floor of the colonial period buildings with its entrance recessed behind a monumental columned portico. With this building and other complexes of the twenty-first century, including New Castle County’s fourteen-story, L-shaped court building in Wilmington, floor plans represented due process by providing space for the service of justice. In the early twenty-first century, the Philadelphia County court system included buildings on Arch, Filbert, and Spring Garden Streets. A new Family Court at Fifteenth and Arch Streets, designed by Philadelphia’s EwingCole, opened in 2014 as a replacement for the Windrim-designed courthouse on Vine Street. Gone were the Beaux Arts references to justice and the paternalistic New Deal era murals; instead, the transparency of the fourteen-story glass tower suggested the virtue Prudence, with her abilities to discern the appropriateness of actions. Concurrently, the city’s traffic court moved from its home in the William Steele & Sons designed Studebaker Building (1918) on North Broad Street, Philadelphia’s Automobile Row, to more modern space on Spring Garden Street.

Thus the courthouses of Philadelphia and the surrounding region underwent rebuilding, renovation, and replacement as demands on the court system rose. These architectural expressions of civic pride echoed local building traditions and, in the nineteenth century, expressed national identity as the young republic matured. With modernization and the expansion of democracy, glass-walled courts and an overwhelming series of specialized spaces stripped figural of Justice of her mystique. The administration of law in the ancillary spaces of the courthouse complex, however, preserved the courtroom as the symbol of justice sought and due process for all citizens at work.

Virginia B. Price is a public historian based in the Washington, D.C., area. She received her M.A. from the College of William and Mary and a Master of Architectural History from the University of Virginia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2020, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History