Declaration of Independence

By Michael Karpyn | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

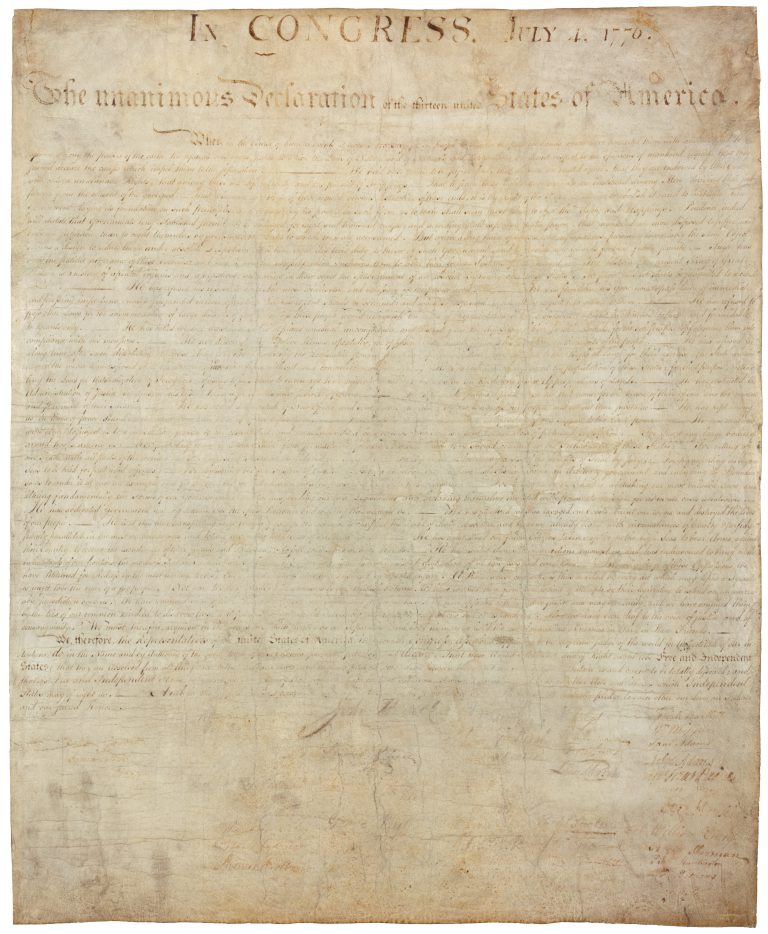

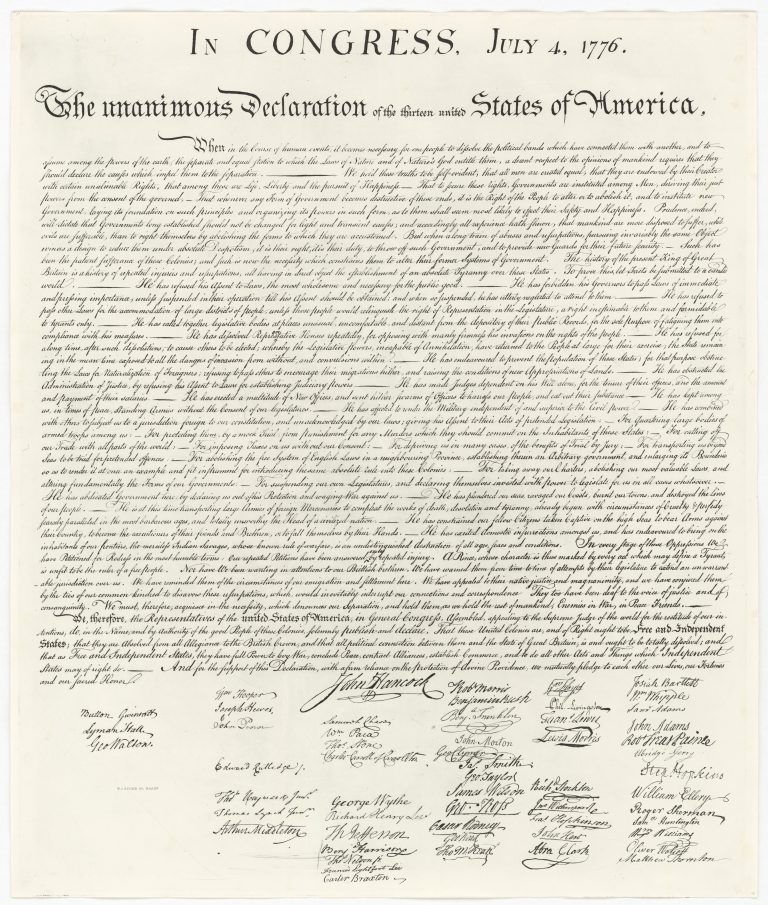

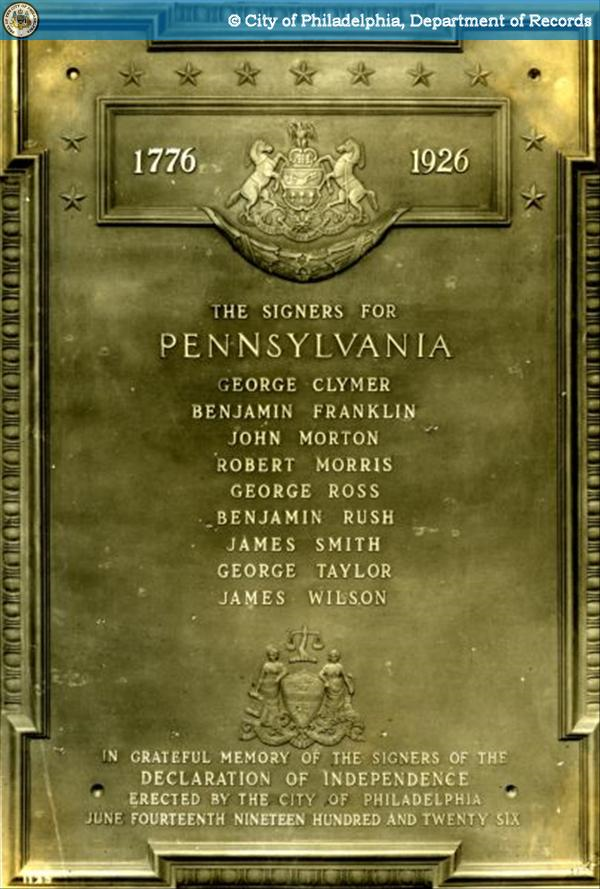

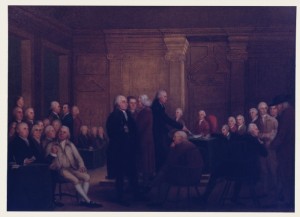

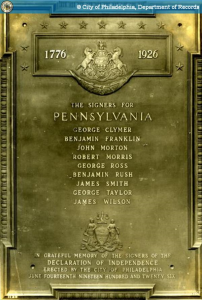

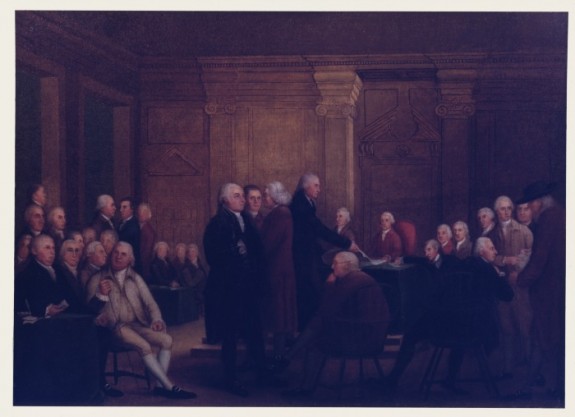

Convening in the East Room of the Pennsylvania State House from May 1775 to July 1776, sixty-five delegates of the Second Continental Congress worked through deep political divisions to create the Declaration of Independence, which gave birth to a new nation and cemented Philadelphia’s reputation as a Cradle of Liberty.

When the Second Continental Congress assembled in Philadelphia in May 1775, the shooting war between British and colonial forces was underway and the delegates faced the task of funding and arming a Continental army, appointing its leadership, and managing a war against its powerful foe. But what about the issue of independence? Even though the war had begun with the Battle of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts a month before, on April 19, 1775, a formal political separation from the British crown was not a foregone conclusion.

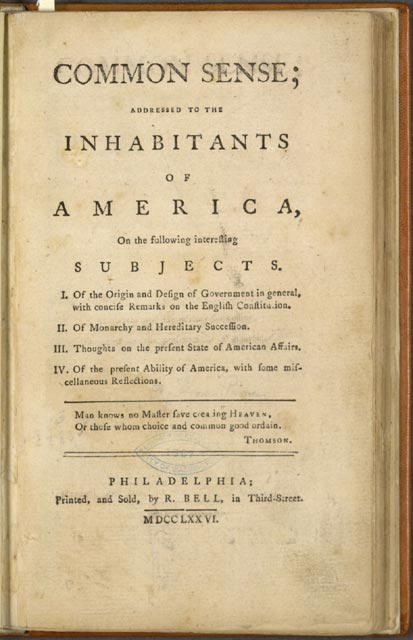

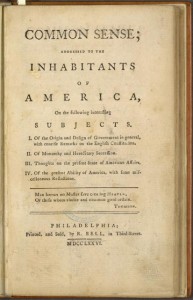

Even in January 1776, a scant six months before the independence was declared, many of the delegates thought that reconciliation with the Crown was the most prudent course of action. On January 9, 1776, Pennsylvania delegate James Wilson (1742-1798) proposed that Congress reject any talk of independence. That same day, the printing shop of Robert Bell near Third and Walnut Streets issued a pamphlet that magnified the desire for independence. Thomas Paine’s (1737-1809) Common Sense, with its rejection of monarchy as a form of government and its impassioned pleas for independence from Great Britain, electrified not only Philadelphia but the thirteen colonies as a whole. While the Continental Congress continued to deliberate, the pamphlet caught fire outside of the elite ranks of colonial America, selling nearly 500,000 copies in its first year of publication.

Between April and July 1776, a groundswell towards independence also emerged in the form of more than ninety local declarations of independence adopted around the colonies. These included resolutions by militia companies in Philadelphia, Chester County, and Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

Not All of One Mind

The colonial governments of Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania did not share in the growing enthusiasm for independence. On May 1, 1776, voters in Pennsylvania elected a new provincial assembly that favored reconciliation. Due to its political and economic influence, Pennsylvania held a great deal of sway over the other colonies. Delaware instructed its delegates to the Continental Congress to “concur” with other delegates but avoided the word “independence.” Virginia, however, moved in the opposite direction and on May 15, 1776, instructed its delegation to declare independence. A new Provincial Congress formed in New Jersey also changed positions, placing the Royal Governor William Franklin (1730-1813), the son of Benjamin, under arrest and sending a new delegation to Philadelphia with instructions to declare independence.

On June 7, Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee (1732-1794) formally presented a plan for the colonies to declare independence, create a national government, and enlist the aid of foreign nations in the war effort. The motion was seconded by John Adams (1735-1826), but political resistance to independence was still deep in the Congress. In Pennsylvania’s case, the provincial Assembly meeting upstairs in the State House remained committed to reconciliation. With passage uncertain, the Continental Congress voted only to resume debate on Lee’s resolution on July 1, 1776.

While those in favor of independence worked behind the scenes to win the votes needed for passage, a committee of five delegates—Adams, Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), Roger Sherman (1721-1793) of Connecticut, Robert R. Livingston (1746-1813) of New York, and Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) of Virginia—set to work on the declaration itself. To complete this most important of tasks, Jefferson moved away from the activity surrounding the State House to the quieter outskirts of the city, at Seventh and Market Streets. Working in rented space on the second floor of the home of bricklayer Jacob Graff, Jefferson completed his draft in roughly two weeks.

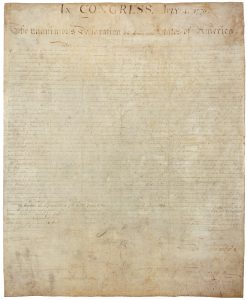

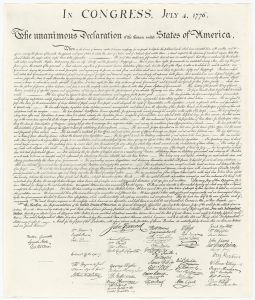

After some minor editing and suggestions from Franklin and Adams, the document was presented to the Congress on June 28, 1776, for further editing and debate. The Congress made more than ninety changes to Jefferson’s draft, from changes in vocabulary and sentence structure to the elimination of some Jefferson’s listed grievances against the King. These changes included removing the charge that King George III had delivered the “un-Christian” practice of slavery to American colonies.

One Vote Per Colony

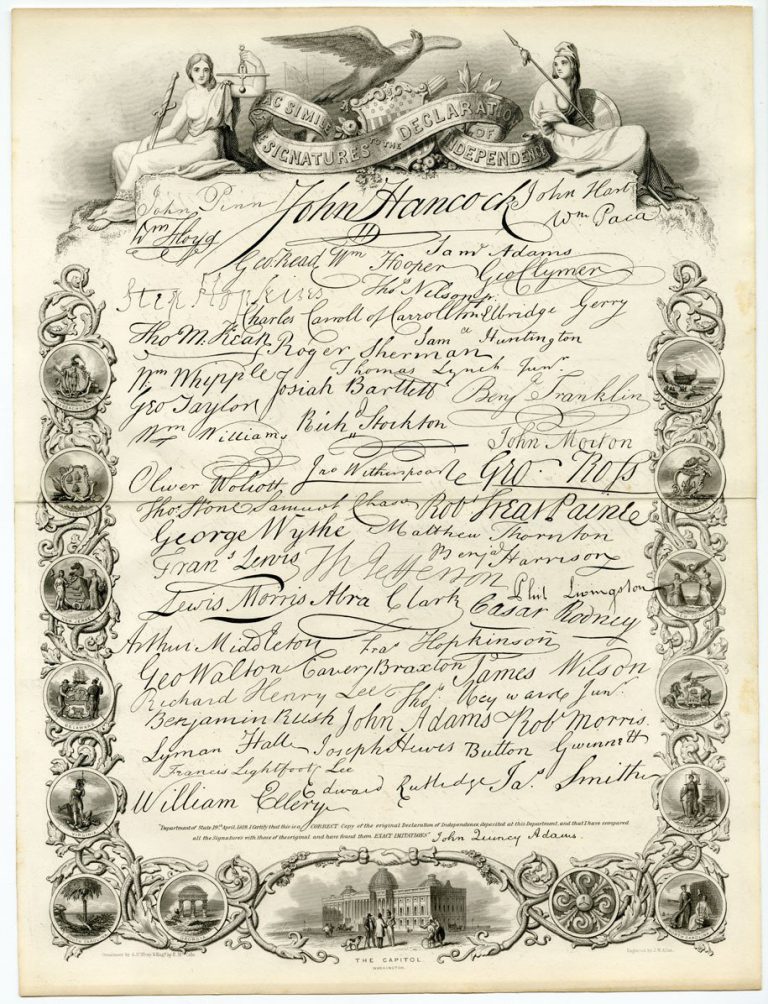

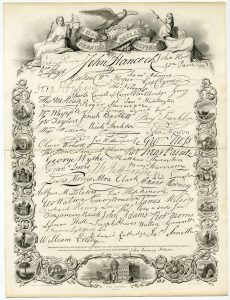

On July 1, after a long day of debate, the Congress voted. Each colony had one vote, requiring the delegations to decide among themselves how to cast their single vote. Pennsylvania and South Carolina voted no; New York—whose provincial government was then fleeing the invading British Army—abstained. Delaware’s two delegates were split. Although a majority of the delegations at this moment voted in favor of the resolution, proponents of independence sought unanimous support.

On July 2, the remaining pieces fell into place. South Carolina reversed course and voted in favor of Lee’s resolution. Delaware’s Caesar Rodney (1728-1784), in an act memorialized in 1999 on Delaware’s commemorative state quarter, rode through the night to arrive at the State House to break his delegation’s tie in favor of independence. Within the Pennsylvania delegation, John Dickinson (1732-1808) and Robert Morris (1734-1806), both opponents of independence, abstained, leaving Pennsylvania’s delegation 3-to-2 in favor of independence. Dickinson, recognizing the symbolic importance of a unanimous decision, did not cast his vote. Realizing he could no longer stay in Congress, Dickinson left and volunteered for the Pennsylvania militia.

The Congress voted unanimously in favor of independence. Some of the delegates—Adams most famously—considered July 2 as the day of American independence. It was July 4, however, when the final editing and wording of the document was approved and sent to Philadelphia printer John Dunlap (1747-1812) at his shop at Second and Market Streets for publication.

Philadelphians first heard the document on July 8, when John Nixon (1733-1808), a Lieutenant Colonel in the Philadelphia militia, read the Declaration of Independence in the State House Yard. The public reaction was passionate and widespread. According to historian William Hogeland, the crowd shouted “God bless the free states of North America!” three times. In the ultimate act of defiance, Pennsylvania militiamen removed the king’s coat of arms from the State House and threw it into a large bonfire.

Thousands of visitors each year visit the Pennsylvania State House, situated then as now on Chestnut Street between Fifth and Sixth Streets. They may not be aware of its history as a State House or that the Georgian style of its architecture expresses deep ties between Pennsylvania and British culture. These visitors are drawn by the significance of this building in the early history of this nation, and know it better by the name it gained from the events of 1776—Independence Hall.

Michael Karpyn teaches History, Economics, and Advanced Placement U.S. Government and Politics at Marple Newtown Senior High School in Newtown Square, Pennsylvania. He has served as a Summer Teaching Fellow at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, where he is a member of the Teacher Advisory Group. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- The Declaration of Independence (National Archives)

- Interpreting the Declaration of Independence by Translation

- Journals of the Continental Congress (Library of Congress)

- Thomas Paine, Common Sense (Project Gutenberg)

- The Great Essentials (Independence National Historical Park)

- For Teachers: The Declaration of Independence, "An Expression of the American Mind" (NEH EdSITEment)

- Examining Independence Hall (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (Princeton University)

- Jefferson's Draft of the Declaration of Independence (American Philosophical Society)

- The House where Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- When and How Did the Colonies Find Out About the Declaration? (Harvard University)