Forts and Fortifications

Essay

Constructed from the seventeenth through the mid-twentieth century, defensive fortifications along the lower Delaware River and bay guarded the region during times of international and sectional upheaval. As important structures with such long histories, forts help to explain the political, economic, and social history of the Greater Philadelphia region.

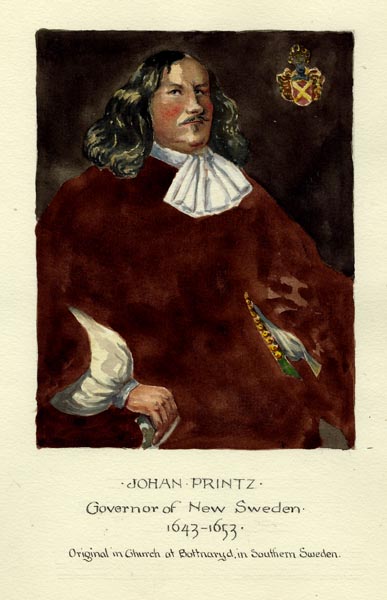

The earliest fortifications in the lower Delaware region resulted from the intense economic colonial rivalries and wars of the early seventeenth century, as Dutch, Swedish, and English Protestant capitalist states battled Spanish, Portuguese, and French Catholic kingdoms for control of the North American and West Indian trade and settlement. Their rivalry led to construction of Fort Nassau, built in 1626 by the Dutch West India Company on the east bank of the Delaware (the future site of Gloucester City, New Jersey), and Fort Christina, built in 1638 by the New Sweden Company at the confluence of the Christina River and Brandywine Creek (the future site of Wilmington, Delaware). Both fortifications served as centers for fur trading, and Fort Christina also developed as an agricultural settlement. The New Sweden Company dispatched more than a dozen expeditions over the next decade bringing Swedes, Finns, Dutch, and German settlers to the Delaware, then known as the South River. When Lieutenant Colonel Johan Bjornson Printz (1592-1663), a veteran of the Thirty Years War (1618-48), became governor of New Sweden in 1643 he further fortified the colony with Fort Nya Elfsborg (Elsinboro, Salem County, New Jersey) and Fort New Gothenburg (Tinicum Island, Pennsylvania) upriver on the west bank a mile south of Fort Nassau.

The Dutch West India Company naturally responded to New Sweden’s threat to New Netherland’s commercial monopoly on the South River by strengthening Fort Nassau, building a number of small, fortified trading posts across the river, and erecting Fort Casimir where the river met the Delaware Bay (later the site of New Castle, Delaware). The new fort stood well below the Swedish forts and promised to stop Swedish ships entering the bay and river. New Sweden soon seized Fort Casimir, but had neither the resources nor manpower to construct and hold such a fort as aggressive New Netherland Director-General Peter Stuyvesant (1612-72) sent a thousand-man expedition up the Delaware in 1655 to retake the defensive works and bring an end to New Sweden.

Britain Prevails Over the Dutch

The regained Dutch influence on the Delaware River was short-lived. In 1664, after the Dutch surrendered New Netherland to the British, they quietly abandoned their forts on the Delaware. Without major threats to control over the region and naval supremacy in the bay and nearby Atlantic coast, the British decided not to garrison fortifications on the Delaware. Spending money on forts or defense also did not interest the Quaker provincial government of Pennsylvania, created by land grant to William Penn in 1681. By the mid-eighteenth century, though, the need for fortifications in the Delaware Valley increased as Britain became locked in a century of colonial warfare with France and Spain.

Greater defenses became an issue by the 1740s as French soldiers and their Native American allies came south from Canada into western and central Pennsylvania to block English westward settlement, while French and Spanish naval forces—particularly privateers from the West Indies—came up the coast and plundered several Delaware Bay and river settlements. Local residents constructed a fortified redoubt in 1748 near Wilmington, but the Quaker assembly in Philadelphia refused to raise money for the city’s fortification. When the French and Spanish threatened Philadelphia’s trade and business, more-militant Quaker merchants joined with a non-Quaker political faction that included Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) to fund defensive measures. During King George’s War (1740-48), Franklin used the sale of lottery tickets to fund the construction in 1747-48 of the Grand (Association) Battery, a great twenty-seven-gun stone wall along the south Philadelphia (Southwark) riverfront, and a smaller Society Hill Battery just upriver. Fortifying the lower Delaware and Philadelphia became more urgent during the French and Indian War, 1754-63, particularly after the British were driven from Fort Duquesne in western Pennsylvania and moved eastward toward Philadelphia. In response, Franklin oversaw construction of a number of fortifications in the Lehigh Valley, where he personally directed the building of Fort Allen (Weissport, Carbon County) in 1755.

The British government, overtaxed by continual warfare against the French in Europe, the Caribbean, Atlantic Ocean, and North America, expected the Pennsylvania Assembly to bear the burden of arming the Delaware Valley, particularly fortifying the Delaware River approaches to Philadelphia. To this end the British army dispatched military engineer Captain John Montresor (1736-99) to fortify Mud Island (also called Fort Island) on the Delaware riverfront near the mouth of the Schuylkill River. Montresor designed a small stone fort and began construction of a southern and eastern wall of the Mud Fort (later Fort Mifflin). Worsening relations between England and her North American colonies interrupted construction until 1775, as the Continental Congress met in Philadelphia and increasingly protested British taxation and trade policies.

1776: Need for Forts Gains Urgency

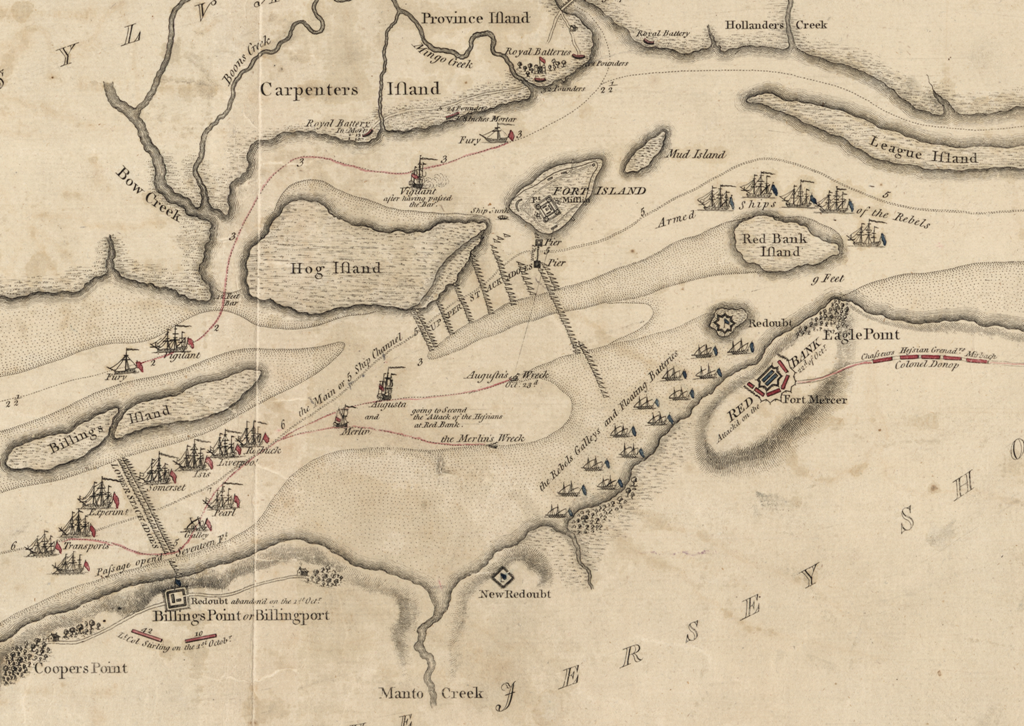

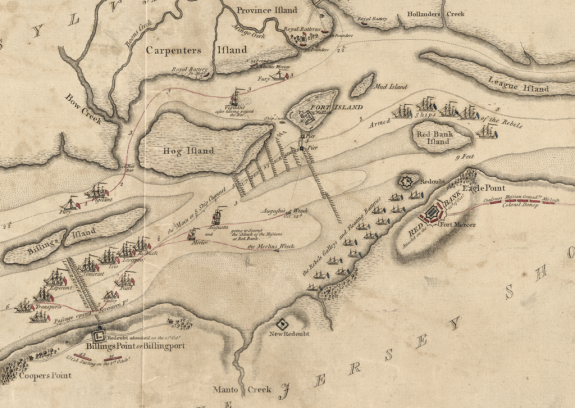

Months of debate over whether Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, or the Continental Congress, should select sites and pay for defensive works along the river reached a critical stage after the American Declaration of Independence. On July 5, 1776, the Continental Congress purchased a site for a fort in Billingsport (Paulsboro), New Jersey. General George Washington (1732-99) asked Col. Thaddeus Kosciuszko (1746-1817), a highly skilled French-trained Polish/Lithuanian military engineer to design the fort, and the Continental Congress hired French military engineer Philippe DuCoudray (1738-77) to build it as an anchor for a chain of frames of large iron-tipped logs known as chevaux-de-frise to be spread across the river channels to prevent British warships coming upriver to attack Philadelphia. Congress also authorized construction of Fort Mercer on a high bluff known as Red Bank, Gloucester County, New Jersey.

The British attack on Philadelphia in late summer and fall of 1777 forced completion and garrisoning of the three Delaware River forts. Fort Billings, defended by local militia, was the first to fall to the British Army, then British naval vessels breached the chevaux-de-frise and slowly moved upriver toward the Mud Island (Fort Mifflin) and Red Bank (Fort Mercer) fortifications. British naval bombardment of Fort Island, reportedly the heaviest cannon fire of the Revolutionary War, reduced the Mud Fort (Fort Mifflin) to rubble. Forts Mercer and Mifflin were abandoned on November 15, and the British Army occupied Philadelphia.

The Revolutionary War marked the last time that forts in the Philadelphia region defended against an enemy force. Nevertheless, fortifications became important while Philadelphia served from 1790 until 1800 as the national capital. President Washington and his secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton (1757-1804), pressed for rebuilding Fort Mifflin and constructing river defenses, particularly with the growing threat of French and British naval incursions in the Delaware during the wars of the French Revolution. The federal government hired civil engineer Major Pierre Charles L’Enfant (1754-1825) to redesign Fort Mifflin and military engineer Anne-Louis de Tousard (1749-1817) to build the bastion. Tousard used government funds to buy material from Philadelphia merchants and hire local German, Irish, and English carpenters and bricklayers. African American slaves, many owned by Tousard, supplied the necessary labor. The fort was named Fort Mifflin in 1795 after Washington’s wartime adjutant general, Thomas Mifflin (1744-1800) of Philadelphia.

The Influence of Naval Arms

Work ceased on Fort Mifflin when the national capital left Philadelphia in 1800 for the Potomac River. Some construction resumed during the War of 1812, but Jeffersonian Republicans preferred to spend money on several temporary batteries of twenty-four-pounder cannon on islands in the Delaware River and use small gunboats to protect the city. Moreover, it seemed that the region should be defended with a fort farther downriver because Fort Mifflin stood too close to Philadelphia to provide adequate defense against increasingly long-range naval armament. The U.S. government began to look at sites near New Castle, Delaware, and Pea Patch Island, a large island in the middle of the Delaware River channel where the river met the bay. Work began on a Pea Patch Island fort soon after the War of 1812. Fire destroyed the partially built fort in 1831, but construction resumed in 1833 on a large stone fortification called Fort Delaware.

Defense of the region became necessary once again with the advent of the Civil War. After the Confederate capture of Fort Sumter in the Charleston, South Carolina, harbor in 1861, the U.S. and Pennsylvania governments demanded the arming of Fort Delaware. They worried that a nearby secessionist movement in the state of Delaware and southern counties of New Jersey threatened the security of the cities of Philadelphia, Chester, and Wilmington, which were rapidly emerging as centers of munitions manufacturing, gun casting, and ironclad shipbuilding. The railroad system carrying troops and material south to meet the rebel forces also passed through these cities. Rumored construction of a huge Confederate Navy ironclad warship particularly disturbed the region, and Fort Delaware needed to mount heavy smoothbore guns and floating mines to stop enemy ironclads from attacking Philadelphia. The federal government began to build a great ten-gun battery on the Delaware City riverfront (Fort DuPont) to protect Pea Patch Island. Fort Delaware and to a lesser extent Fort Mifflin served as prisoner-of-war camps throughout the Civil War. Fort Delaware held more than 30,000 Confederate prisoners and local Southern sympathizers in the extremely unhealthy, disease-ridden Pea Patch Island facility.

The last decades of the nineteenth century became the golden age of American coastal fort building as the United States entered into imperial rivalries with Germany, Russia, England, France, Japan, and particularly Spain, which seemed a threat to American interests in Cuba and the Philippine Islands. As the federal government moved to modernize and strengthen American seacoast defenses, the Philadelphia region gained additional fortification in 1896 with construction of a battery on Finn’s Point, Pennsville, Salem County, New Jersey. Named Fort Mott after New Jersey Civil War and National Guard commander Brigadier General Gershom Mott (1882-84), the new fort created a defensive triangle with Forts Delaware and DuPont to stop any enemy fleet before it could reach the great manufacturing centers upriver at Wilmington, Chester, and Philadelphia.

World Wars Bring Heavier Artillery

Delaware Valley forts played no fighting role during the Spanish-American War, but U.S. entry into the First World War in 1917 brought the prospect of a greater need for defending the region as it continued to be a center for naval and merchant shipbuilding, munitions making, and other war goods. Moreover, the region became a mobilization nexus for troops to be shipped to the European fronts. Forts Mott and DuPont were garrisoned by artillery units. Fort DuPont built more barracks, a hospital, and warehouses to train and equip draftees and house troops and material destined to fight in the Great War. However, the region faced no real threat from enemy forces other than sabotage of defense industries by German agents in New Jersey.

The threat to the region was greater by the time of the Second World War, when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 raised the possibility of long-distance aerial attack. Older, obsolete forts gained new purposes as sites for anti-aircraft batteries, including Fort Mifflin, manned by the first African American Coast Artillery unit. It soon became apparent, though, that the greatest threat to the region during the Second World War came from powerful German U-boats that torpedoed merchant ships and oil tankers off the Jersey and Delaware coasts and lurked just off the Delaware Bay and capes to intercept ships coming out of the Delaware Bay. In response, the United States moved all Delaware River and bay defenses to the seacoast, erecting Fort Miles on Cape Henlopen, near Lewes, Delaware. Fort Miles featured giant, long-range sixteen-inch guns and 90mm anti-aircraft batteries. Round concrete observation and fire-control towers were constructed along the Jersey coast as far north as Sandy Hook and down the Delaware coast to Ocean City, Maryland.

Locating coastal defenses ever farther away from Philadelphia and the Delaware River during the Second World War attested to the increasing spatial dimensions of modern warfare and long-range capabilities of new weapons. It suggested as well the increasing obsolescence of the Greater Philadelphia region’s historic forts. All Delaware River forts were declared war surplus after the Second World War and remaining guns or other military material were removed. Forts Mott, DuPont, and Delaware were given to New Jersey and Delaware and became parts of historic districts and state park systems. Fort DuPont retained a National Guard armory. Fort Mifflin was eventually obtained by the city of Philadelphia and supported by a private Fort Mifflin Society to preserve one of the most historic forts in American history. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers retained a presence on site. None of the early seventeenth-century forts remained, but plaques and monuments marked the original sites of Forts Elfsborg, Billings, Mercer, Casimir, and Christina. The surviving structures and monuments and plaques served as reminders of the central role forts played in the earliest history of the Greater Philadelphia area.

Jeffery M. Dorwart, Professor Emeritus of History, Rutgers University, is the author of histories of the Philadelphia Navy Yard; Fort Mifflin of Philadelphia; Naval Air Station Wildwood; Camden and Cape May Counties, New Jersey; Office of Naval Intelligence; Ferdinand Eberstadt and James Forrestal. He also is the co-author of Elizabeth Haddon Estaugh: Building of the Quaker Community of Haddonfield, New Jersey, 1701-1762 (Historical Society of Haddonfield, 2013). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University