Gospel Music (African American)

Essay

Long an important center of African American musical life, Philadelphia played a key role in the development of Black gospel music. One of the seminal figures in developing the gospel style, Charles Albert Tindley (1851-1933), moved to Philadelphia during the Great Migration of the early twentieth century and became a well-known gospel songwriter. As the region’s African American population grew and Black churches flourished, Philadelphia served as home base for many of the music’s biggest stars who settled in the city during the mid-twentieth century “golden age” of gospel.

Gospel music emerged from urban African American churches in the early twentieth century, growing out of longstanding sacred Black music traditions. In colonial Philadelphia, African Americans sang sacred songs from their African homelands as well as European-derived psalms and hymns that they infused with African elements. The music became more formalized in the city’s first Black churches in the 1790s, particularly Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded in 1794 by Richard Allen (1760-1831). In 1801 Allen published a hymnal for his congregation titled A Collection of Spiritual Songs and Hymns Selected From Various Authors by Richard Allen, African Minister, the first American hymnal compiled for a Black congregation. Allen later issued expanded editions of the hymnal, which included primarily traditional Protestant hymns along with some he wrote himself.C

While gospel music first developed in urban Black churches in the North, its roots lay in the rural South. Prior to the Civil War, the harsh conditions of slavery in the South produced two major African American vocal traditions: the blues and the Negro spiritual—the former secular, the latter sacred. Spirituals, the great body of African American religious folk songs, served as the foundation for gospel.

Following the Civil War, African Americans migrating from the South brought their musical traditions to northern cities, where the urban environment gave rise to a new kind of worship music, the gospel song. In contrast to spirituals, which were improvisatory folk songs passed down orally, gospel songs were composed, formally structured tunes that incorporated elements of popular music and blues. Their lyrics reflected the new realities of urban Black life.

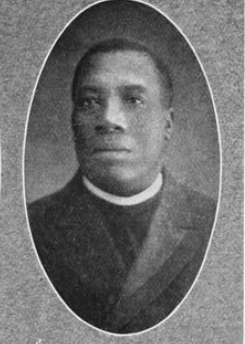

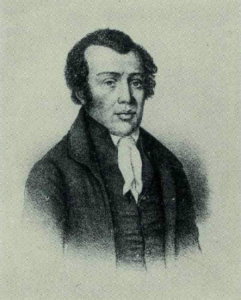

Charles Albert Tindley

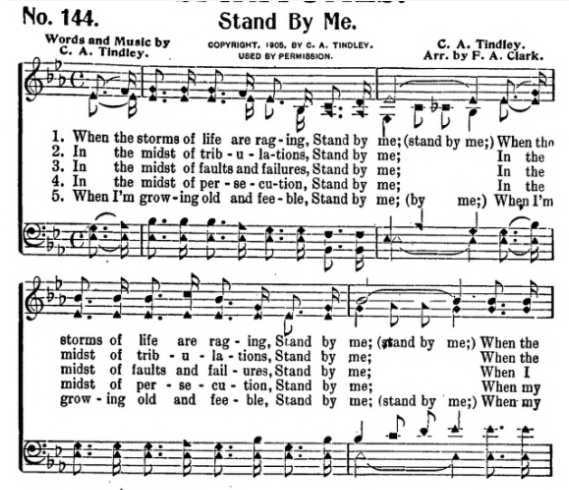

One of the creators of the gospel style, Charles Albert Tindley, moved to Philadelphia during the increasing wave of African American migration from the South at the turn of the twentieth century. Born into a slave family in Maryland and largely self-taught, Tindley became pastor of Bainbridge Street Methodist Episcopal Church (later renamed Calvary Methodist Episcopal Church) in South Philadelphia in 1902. Under his leadership, the congregation expanded significantly and in 1906 moved to its longtime location at Broad and Fitzwater Streets (where it was later renamed Tindley Temple). Tindley wrote gospel hymns, which he began publishing in 1901, the first such songs in the new style to be published. He later issued several gospel hymn collections, published by companies he helped to establish. Through preaching and singing, songwriting, publishing, and radio broadcasts, Tindley became an important figure in gospel music in Philadelphia and beyond. Several of his hymns became gospel standards, including “I’ll Overcome Someday,” which served as the inspiration for the well-known civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome.” Six of his hymns appeared in Gospel Pearls, a collection published in 1921 that was the first hymnal geared toward African American congregations to use the word gospel in the title.

Tindley sometimes has been called the “Father of Gospel Music,” but most historians give this title to Thomas Dorsey (1899-1993), the Chicago-based pianist and songwriter who originally worked in blues before turning to gospel in the early 1930s. Following in Tindley’s footsteps, Dorsey became a prolific gospel songwriter and promoter. An astute businessman as well as musician, he successfully marketed his songs, founded gospel choirs and conventions, and promoted the career of Mahalia Jackson (1911-72), the most famous gospel singer of the twentieth century. Dorsey and other gospel songwriters of the period, most of whom acknowledged Tindley’s influence, helped to usher in the “golden age” of gospel in the 1940s and 1950s, a time when Black congregations across the nation sang gospel music in their worship services and gospel recording artists and performers enjoyed great popularity.

Several distinct musical styles developed within Black gospel. More-traditional Baptist and African Methodist Episcopal congregations generally took a reserved approach. Their performances, while spirited, retained traditional song forms and harmonies and they rendered the songs in a dignified manner. Conversely, in Pentecostal or “holiness” churches, the music was highly charged and improvisatory, with exuberant shouting, hand clapping, and dancing. The Church of God in Christ, a denomination founded in the 1890s, became the chief home of the Pentecostal style. The repertoire of these churches varied, from centuries-old Protestant hymns, to Negro spirituals, to the gospel songs of Tindley, Dorsey, and others. The use of instruments also varied. Some congregations and performers sang a cappella, eschewing instruments as too secular. Others employed instrumental accompaniment, from just a guitar or tambourine to a full band.

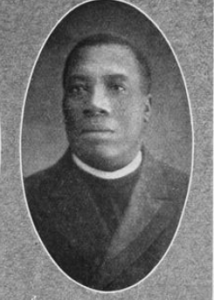

One of Philadelphia’s preeminent churches in the Pentecostal style emerged under the leadership of Ozro Thurston Jones (1891-1972), who moved from Arkansas to Philadelphia in 1925 to assume the pastorship of Holy Temple, a small Church of God in Christ congregation located in West Philadelphia. Holy Temple was originally located at Fifty-Seventh and Vine Streets before moving to Sixtieth and Callowhill Streets in 1935. For a time, the congregation included Elizabeth Dabney (c.1890-1967), a Virginia native who became a leading figure in the Church of God in Christ. She later helped her husband, a singing preacher, establish another prominent Church of God in Christ congregation, Garden of Prayer, in North Philadelphia. Gertrude Ward (1901-81), who moved to Philadelphia from her native South Carolina around 1920, attended the lively services at both Holy Temple and Garden of Prayer regularly, bringing her daughters Clara (1924-73) and Willarene (Willa, 1920-2012). The three later formed the nucleus of the Ward Singers—also known at various times as the Famous Ward Singers and Clara Ward and the Ward Singers—one of the most popular gospel groups of all time.

Singers Drawn to Philadelphia

By the mid-twentieth century, gospel emanated from the numerous churches in the growing Black neighborhoods of South, North, and West Philadelphia, as well as other cities in the region with significant African American populations. Some of the biggest names in gospel music moved to Philadelphia from the South in this period, including the nationally popular male quartets the Dixie Hummingbirds and the Sensational Nightingales. Soon after settling in the city in 1942, the Dixie Hummingbirds secured a daily program on radio station WCAU, laying the groundwork for a long, successful career. In the mid-1940s, Hummingbirds singer Ira Tucker (1925-2008) began staging gospel shows at the Metropolitan Opera House at Broad and Poplar Streets in North Philadelphia. Featuring his own group and other local and national gospel acts, these very successful shows made “the Met” an important gospel venue.

Philadelphia became known especially for its female gospel groups, including the Ward Singers, Davis Sisters, Stars of Faith, and Angelic Gospel Singers. Of these, the Ward Singers achieved greatest success. Performing in elaborate gowns and hairstyles, they took gospel into nightclubs and jazz festivals, which enhanced their popularity but alienated more-conservative gospel adherents. Marion Williams (1927-94) moved to Philadelphia from Florida in 1947 to join the Ward Singers and sang with them for eleven years before breaking away to form the Stars of Faith and later embarking on a solo career. Considered one of the greatest gospel singers of all time, Williams was honored by the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 1993. Mary Johnson Davis (1899-1982), an influential singer and group leader who moved in the 1950s from her native Pittsburgh to Philadelphia, maintained an active performing career and, with her friend Gertrude Ward, nurtured gospel talent in the area.

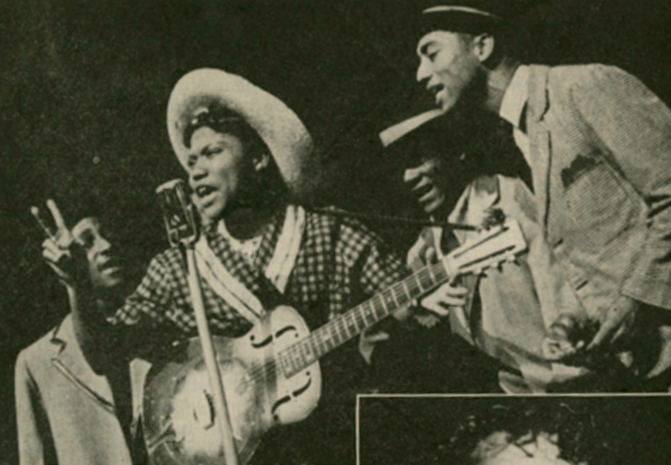

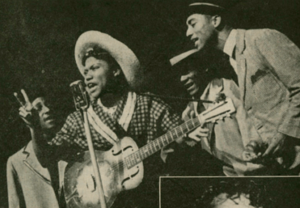

Singer/guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe (1915-73), perhaps the most successful—and unusual—female gospel artist of the period, moved to Philadelphia in 1957 after years of touring and living in other cities. Major gospel artists routinely received tempting offers to cross over to the more lucrative secular world of jazz, rhythm and blues, and popular music. While a number of prominent gospel singers refused to abandon sacred music, many did make the transition, to the consternation of their more traditional audiences. Uniquely, Tharpe moved back and forth between secular and sacred music several times in the course of her career, enjoying great success in both realms. Tharpe also developed a distinctive virtuoso guitar style, earning her the title “Godmother of Rock and Roll.”

Changes in society, musical tastes, and the music business in the 1960s signaled an end to the golden age of gospel, as well as other Black music styles. While traditional gospel remained popular, a new “contemporary” gospel style began to emerge, incorporating elements of modern popular music and often featuring elaborate musical arrangements and sophisticated recording techniques. Gospel music, both contemporary and traditional, remained an active, thriving tradition into the early twenty-first century in the Philadelphia area. It formed an integral part of the services of Black churches throughout the region and gospel artists continued to enjoy the support of loyal audiences who listened to local gospel radio stations and attended concerts at churches and major venues such as the Robin Hood Dell and Temple University’s Liacouras Center.

Jack McCarthy is an archivist and historian who specializes in three areas of Philadelphia history: music, business and industry, and Northeast Philadelphia. He regularly writes, lectures, and gives tours on these subjects. His book In the Cradle of Industry and Liberty: A History of Manufacturing in Philadelphia was published in 2016 and he curated the 2017–18 exhibit “Risk & Reward: Entrepreneurship and the Making of Philadelphia” for the Abraham Lincoln Foundation of the Union League of Philadelphia. He serves as consulting archivist for the Philadelphia Orchestra and Mann Music Center and directs a project for Jazz Bridge entitled Documenting & Interpreting the Philly Jazz Legacy, funded by the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Gospel Roots of Rock and Soul (WXPN)

- Clara Ward and the Ward Singers (Philadelphia Music Alliance)

- The Dixie Hummingbirds (Philadelphia Music Alliance)

- Tindley Temple (United Methodist Videos via YouTube)

- Gospel Pearls (HathiTrust.org)

- Sister Rosetta Tharpe (Philadelphia Music Alliance)

- Sister Rosetta Tharpe (All That Philly Jazz)

- Amazing Grace, sung by Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Lottie Henry and the Rosettes (Library of Congress)

- Marion Williams (Philadelphia Music Alliance)