Great Awakenings

By Hans Leaman

Essay

The Philadelphia region played a major role in the three major religious “awakenings” that shaped American religion and popular culture in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Religious revivals were common experiences encouraged by evangelical Protestant churches as ways to convert people to religion or to renew their faith. Often termed “great awakenings” for their emotional effects in stirring spiritual reflection and then excitement, they were usually carefully managed events that involved powerful preaching, hymn singing and music, staging for effect, and mass gathering of people. The diverse range of Protestant groups in the Philadelphia region made it a fertile ground for cross-denominational collaborations that, for many people involved, signaled an “awakening” from staid religious practices, and the founding of large nondenominational publishing houses in Philadelphia provided a means to extend such revivals through the publication of religious tracts, newspapers, and other printed material to other parts of the nation.

The “First Great Awakening”

Because of its high level of religious and linguistic diversity, the Philadelphia region experienced a wide variety of forms that Protestant revival could take in the first “Great Awakening” of the 1730s and 1740s. When English-speaking evangelical preachers came through Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey, their advocacy of “heartfelt” religion merged neatly with the Pietist emphases that many German, Swedish, and Dutch settlers had brought from Europe after their struggles with Lutheran and Reformed church leadership there. Both evangelical and Pietist believers emphasized that individuals can experience the joy of “true conversion” by humbly yielding to the promptings of the Holy Spirit. By featuring many personal testimonies to the transformative grace of God, the itinerant preachers’ meetings tended to cut through denominational, class, and gender lines and lay bare the common condition of all people. Throughout the mid-eighteenth century, most Philadelphia-area churches grappled intensely with the populist implications of this evangelical preaching. When theological precision mattered less than a man’s heartfelt account of his cleansing from sin, clerical authority based on education-based distinctions came under threat.

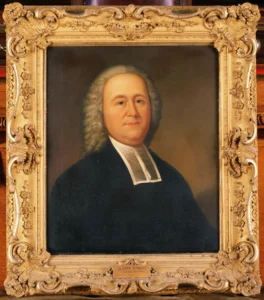

Early challenges to religious norms in the mid-Atlantic colonies arrived with the immigration of Theodorus Frelinghuysen (c. 1691-1747), a Dutch Reformed missionary, to New Jersey and William Tennent (1673-1746), an Edinburgh-educated Presbyterian clergyman, to Pennsylvania. While Frelinghuysen cultivated a Pietist devotional life among the settlers of the Raritan Valley, Tennent set up an academy near Warminster around 1735—the first college in the colony. Dubbed the “Log College” after its humble meetinghouse, it produced a number of revivalist preachers prepared to criticize religious complacency among the Presbyterian churches. Most notable among them were Tennent’s own sons, Gilbert (1703-64) and William Jr. (1705-77), who later became founding trustees of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University). Gilbert Tennent’s 1740 tract, The Dangers of an Unconverted Ministry, issued an opening shot against a Presbyterian clergy more concerned with the prerogatives of their offices, in the Tennents’ view, than experiencing a personal encounter with the grace of God. Presbyterian supporters of the Tennents’ emphasis on conversion became known as the “New Side” in Pennsylvania—akin to the “New Lights” among the Congregationalists in New England who supported Jonathan Edwards (1703-58) and the revivalist preaching of itinerants there. The Presbyterian Synod of Philadelphia, holding up the “Old Side,” pushed the New Side ministers into the revivalist-leaning Synod of New York. The schism illustrated that the awakening could unify as well as fragment churches, depending on members’ emphasis on expressive individual piety or dependable order for authority and worship.

The Tennents and Frelinghuysen found a great boost to their cause when the English evangelist George Whitefield (1714-70) arrived in Pennsylvania in fall 1739 on his second tour up the Atlantic Seaboard. New Side Philadelphians joined “low church” Protestants in thronging to his sermons. Philadelphians did not tire of Whitefield’s preaching during the visits he made over the next twenty years. After Whitefield’s first stay, they raised funds to build a meeting hall at Fourth and Arch Streets to host his sermons—the largest edifice in the city at the time.

The awakening also became a publishing phenomenon for Philadelphia’s printing houses, as the population became eager readers of theological and devotional texts. When Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) published collections of Whitefield’s sermons and journals, demand well outpaced his printing. Germantown printer Christoph Sauer (1695-1758) soon followed with German translations of the evangelist’s sermons. Philadelphia’s newspapermen were happy to print the animated commentaries that Whitefield’s dramatic preaching style provoked. The controversy made good business, pointing to religion’s status as a matter of general public concern.

(Wikimedia)

The awakenings extended to the region’s Native Americans. Among the various German Pietist sectarians who had settled north and west of the city, Moravians usually led cross-confessional worship meetings and they became the most successful of European religious groups in forging trustful relationships with the Native tribes. Their unique forms of affective piety, with prominent feminine metaphors for divinity, were reflected in Natives’ own appropriations of Christianity. Until the Seven Years’ War, Mahican, Lenape, and Shawnee converts lived side-by-side with Moravians in a settlement in the Lehigh Valley. Through the efforts of Presbyterian missionary David Brainerd (1718-47), Lenape converts also set up a “praying town” in Cranberry, New Jersey, where their leaders replicated revivalist themes of prophetic preaching, personal confession, and the power of the Holy Spirit.

The “Second Great Awakening”

The Second Great Awakening is typically associated with “camp meeting” revivals in the 1820s and 1830s on the Appalachian frontier and the “Burned-Over District” of upstate New York. But a new era of religious renewal and organizational realignment had already begun in the Philadelphia region in the 1780s and 1790s. Circuit-riding Methodist preachers made significant inroads among the population during this time. The ministry of Francis Asbury (1745-1816) in the Delmarva Peninsula made it the most concentrated area of American Methodism in British North America and launched him into a position of spiritual authority that he used to organize pastoral care throughout the new nation. The Second Great Awakening emanated from a surge of young men who devoted themselves to pastoral ministry and evangelism, regardless of academic training.

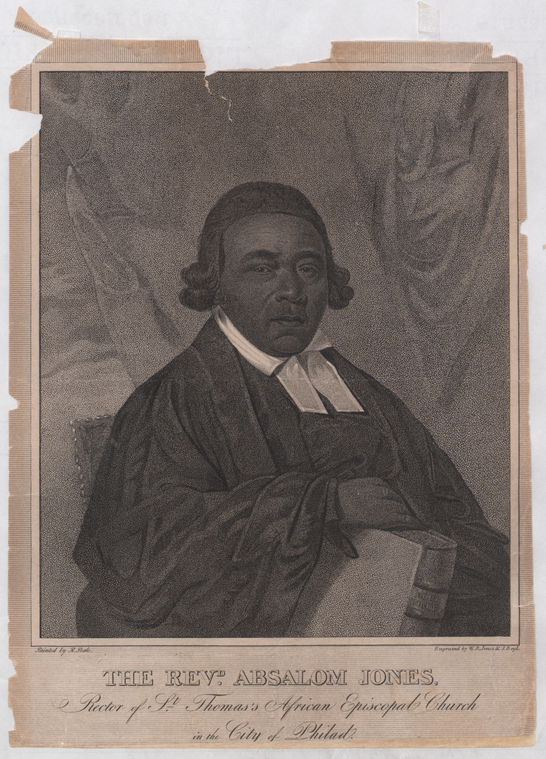

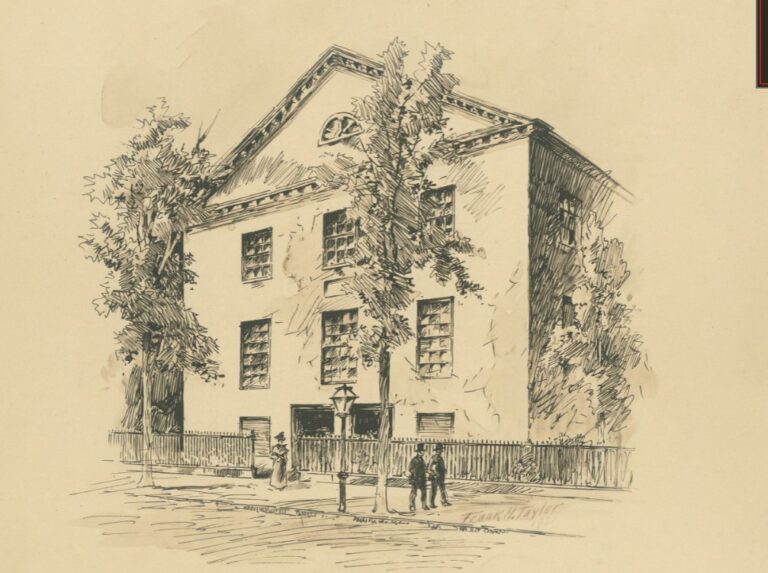

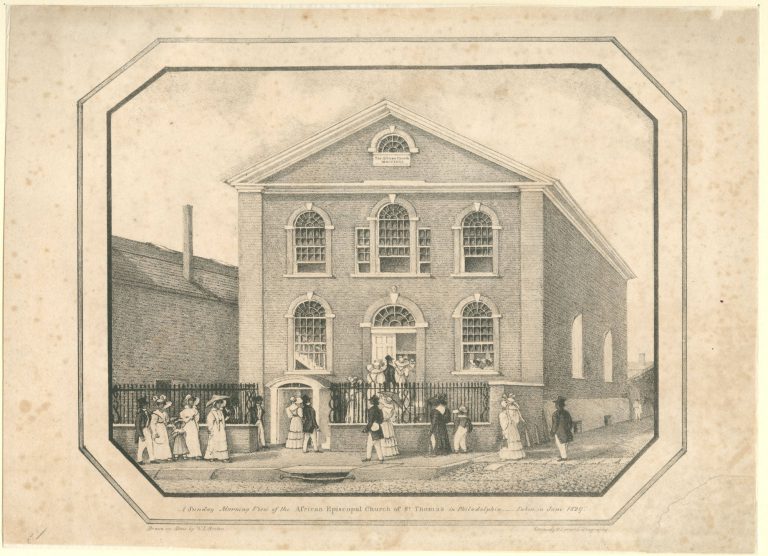

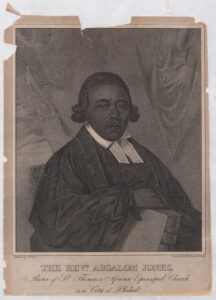

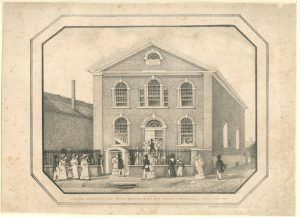

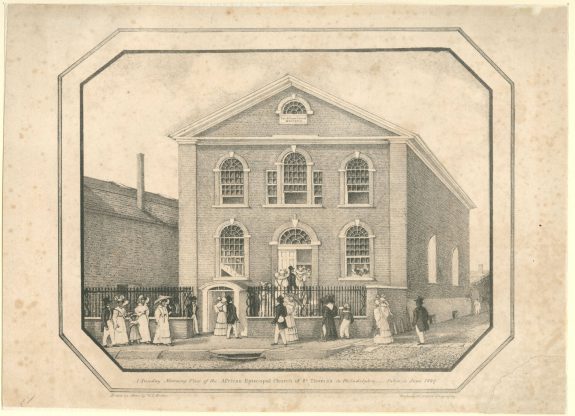

Many free Black residents of Philadelphia, as well as enslaved Black people in Delaware and New Jersey, were attracted to Methodist spirituality. Among them was Richard Allen (1760-1831), who was able to purchase his freedom after his owner experienced a religious conversion and became morally “convicted” that slaveholding was wrong. Allen became a compelling Methodist preacher, traveling throughout the Mid-Atlantic states. He also began preaching frequently at St. George’s Methodist Church and evangelizing Black people in Philadelphia. But as fluid revivals solidified into church routine, racial segregation also became routine in the church. Allen responded by organizing a new Methodist church named Bethel, and his associate, Absalom Jones (1746-1818), formed the St. Thomas African Episcopal Church. Almost thirty years later, in 1816, Allen led seventeen congregations to form the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church. The church and its auxiliary societies were among the few national organizations in which Black men and women had the opportunity to exercise leadership, empowering them with a sense of ownership, independence, and participation in church life.

Philadelphia’s role as a center for social reform in the antebellum era made it the setting for the rise of important interdenominational mission and education societies. The Sunday School movement, begun in England in the 1780s, found its prime American model when a group of Philadelphia pastors and merchants founded the First Day Society in 1791. The society paid local schoolmasters to teach boys and girls, as well as illiterate men and women, to read and write while using the Bible as the textbook. In 1817, a new generation of Philadelphia businessmen founded the Sunday and Adult School Union, this time organizing a cadre of volunteer teachers to spread out through the poorer parts of the city with their literacy skills and evangelical mission. Within one year, the union had opened forty-three Sunday schools in the city and was instructing 5,970 pupils. By 1824, the society had expanded nationally, hiring missionaries who started Sunday schools in both urban and rural areas, as well as Native American reservations. Changing its name to the American Sunday School Union, it acted as a major publisher of Sunday school and Vacation Bible School materials throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Its missionaries became active advocates for African Americans’ and Native people’s voting and educational rights.

The Awakening took on more immediate political significance through its implications for slavery. Philadelphia’s evangelicals, taking their cues from the successful campaign of William Wilberforce (1759-1833) to end the slave trade in Britain, joined with Quakers to try to purge the sin of slavery. Many itinerant preachers, who stressed the equality of all men before God, sought to persuade white people that their faith entailed emancipating their slaves and supporting emancipation elsewhere. In 1833, abolitionists gathered in Philadelphia to organize the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) and the Philadelphia Female Antislavery Society (PFASS), calling for immediate, rather than gradual, abolition. While William Lloyd Garrison (1805-79), an evangelical Baptist at the time, led the AASS, the leaders of the PFASS, such as Lucretia Mott (1793-1880), came largely from the Hicksite Quaker movement. The Hicksites, formed in the 1820s, emphasized that Quaker business and consumer relationships should not be contaminated with associations to enslaved labor. Such heightened interests in antislavery work, however, sometimes encountered resistance from Philadelphia-area religious leaders concerned about politicizing the church to the detriment of other evangelical work.

The “Third Great Awakening”

Philadelphia-area religious leaders pioneered the mass-marketed prayer meetings and tent revivals that characterized the “Third Great Awakening” of the late 1850s, providing a model for successful evangelistic services that continued to influence American religious life into the twentieth century. This third revival began against the backdrop of the Bank of Pennsylvania’s collapse on September 25, 1857. The bank’s failure, amid rapidly declining valuations of railroad companies, reverberated on Wall Street, where the stock market crashed fifteen days later. Over the prior year, the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) had been sponsoring a noontime prayer meeting at a church in New York’s financial district. In the unsteady autumn days of 1857, it became a place where unchurched businessmen began to throng.

Through the YMCA network, the idea to hold noonday prayer meetings traveled quickly to Philadelphia, where the fledgling local chapter was led by prominent businessman George Hay Stuart (1816-90) and a young retail clerk named John Wanamaker (1838-1922). In November 1857, they first held prayers in the Methodist meetinghouse originally built for Whitefield, and in 1858 they moved to Jayne’s Hall in the heart of the financial district. Wanamaker also organized a Sunday school in a volunteer firemen’s hall and boosted interest in both meetings by taking out advertisements in the city newspapers under the banner: “Jesus is Coming!” By March the papers were reporting on a “Religious Awakening,” and Wanamaker needed to organize more sites for noonday prayer meetings around the city’s commercial center and wharves. Even the telegraph companies lent their support by offering to send “revival messages” and prayer requests free of charge during the noon hour. Civic leaders were particularly pleased about reports of spiritual and moral reform among the city’s fire companies, which were previously known to be a source of drunkenness and street fighting.

Likely the most consequential of the Philadelphia prayer meeting converts was Hannah Whitall Smith (1832-1911). Describing herself as a Quaker-born skeptic of Christianity in her autobiography, Smith initially viewed the noonday prayer meetings as “only another effort of a dying-out superstition to bolster up its cause.” But while grieving the death of her young daughter, she attended a prayer meeting. There, she recalled, “somehow an inner eye seemed to be opened in my soul, and I seemed to see that after all God was a fact—the bottom fact of all facts. … God was making Himself manifest as an actual existence, and my soul leaped up in an irresistible cry to know Him.” Smith went on become a leader within the Holiness movement, which generated many of the religious revivals and controversies of the late nineteenth century. She traveled throughout North America and Europe, emphasizing the possibility of “entire sanctification” and the “higher life,” and wrote the best-selling book The Christian’s Secret of a Happy Life (1875).

The Methodist-leaning branch of the Holiness movement had an anchor in Philadelphia after the success of two camp revivals in the region in the 1860s. In 1867, an estimated ten thousand people gathered for a camp meeting in Vineland, New Jersey, where participants founded the National Camp Meeting Association for the Promotion of Holiness. The second meeting, in 1868, attracted twenty-five thousand people to a farm outside Manheim, Pennsylvania. The Camp Meeting Association chose Philadelphia as its headquarters, establishing an influential missionary board and a publishing house for its many tracts while planning camp meetings around the nation well into the twentieth century.

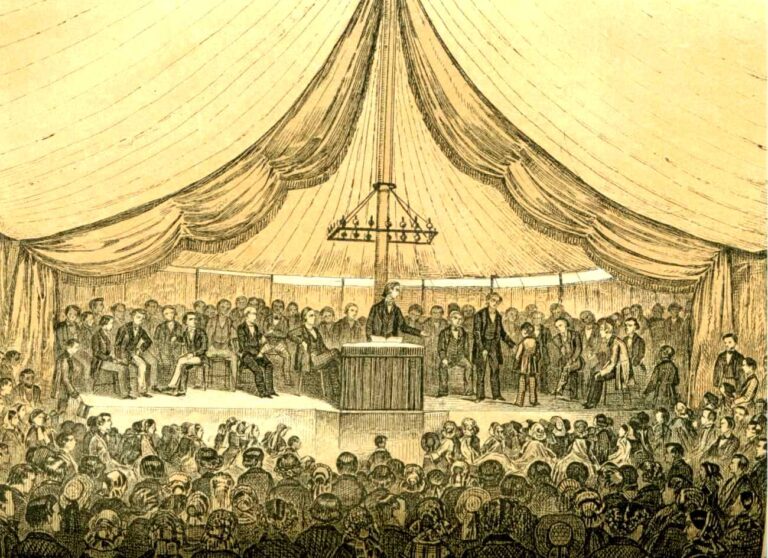

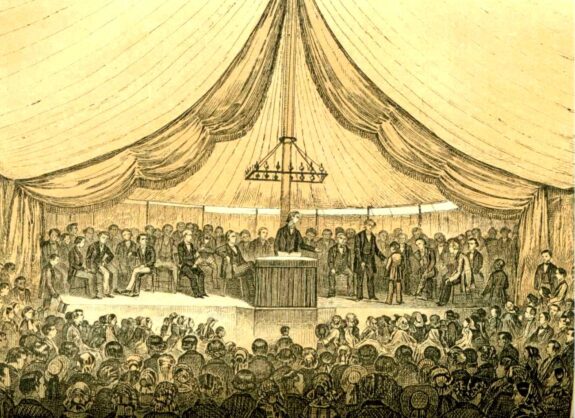

Leaders of Philadelphia’s 1858 prayer meetings also pioneered the “tent revival,” which became a mainstay of American religious life for more than a century, into the era of evangelist Billy Graham (1918-2018). In spring 1858, Wanamaker approved the purchase of a circus tent capable of seating two thousand people. Dubbing it, appropriately, “The Union Tabernacle” or the “Moveable Tent-Church,” the YMCA moved it from neighborhood to neighborhood, holding services day and night for several weeks at a time. The idea for the tent came from Edwin McKean Long (1827-94), a Presbyterian missionary based in Norristown who had been evangelizing the rural German-speaking population in southeastern Pennsylvania. The casual, festival-like atmosphere of the tent proved attractive to working-class and immigrant residents who might have otherwise viewed themselves as too poorly dressed to attend formal church services or the prayer meetings in the business district. By the time the tent was decommissioned in 1861, the YMCA estimated that between 150,000 and 170,000 people had attended services inside the tent. Fifteen years later Stuart and Wanamaker—by then the owner of the city’s best-known department store—used their marketing acumen to make the revival meetings of Dwight L. Moody (1837-99) a major regional event. Over the course of nine weeks in the winter of 1875-76 more than one million people attended services inside the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Grand Freight Depot, many traveling from rural towns now linked to the center city by regional rail lines.

The large camp and tent meetings proved to be models for evangelism throughout the United States in the industrial era. Most notable among them was the Billy Sunday (1862-1935) campaign in Philadelphia in 1915, an event that received such admiring coverage from the local press that Sunday once quipped that he would point towards Philadelphia when God called him to account for his life: “I gave them your message, Lord, I gave it to them the best way I could and as I understood it. You go get the files of the Philadelphia papers.” It was a comment that Whitefield could have also made 175 years earlier.

Since individuals and single congregations in a large city like Philadelphia experience religious conversion and revival every day, there is an element of artificiality involved in designating specific time periods as “great awakenings.” Still, the designation can be useful to focus attention on moments when increased collaborations among ministers and laypeople across denominational lines create public forums for mass preaching and prayer outside of congregational services; build new organizations for instructing the unchurched; and challenge established authorities whom they perceive to be impeding spiritual and moral reform. The Philadelphia region experienced each of these dynamics during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and many organizations that Philadelphians created during these moments of awakening proved to have national significance.

Hans Leaman (Ph.D. Yale University; J.D. Yale Law School) is Academic Dean and Associate Professor of History at Sattler College in Boston, Massachusetts. He is originally from Bird-in-Hand, Pennsylvania, in Lancaster County. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2026.