Hotels and Motels

Essay

As one of the busiest and most influential port cities in colonial and later independent America, Philadelphia became an early leader in hotel development and continued to elevate industry standards throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Hotels presented travelers with a desirable alternative to staying in private residences, and luxury hotels became signifiers of a city’s economic and social health. In the early decades of the twentieth century, the hospitality industry came to be dominated by motels, which accommodated families traveling by automobiles by providing basic amenities with popular entertainment options. Architecturally, hotels and motels responded to changing leisure preferences, new construction techniques, and shifting patterns of urbanization.

The earliest hotels in Philadelphia were influenced by the well-established practices of colonial-era tavern hospitality. However, while taverns provided basic lodging, hotels elevated standards of extravagance and cleanliness and catered to a variety of travelers, from single businessmen to couples and families. Although luxury accommodations began to emerge in the 1820s, more modest hotels continued to serve travelers and were frequently affiliated with the industries that built them, for example Philadelphia’s coffeehouses and oil cloth manufactories. Early hotels that accommodated working-class visitors shared buildings with at times several other businesses, including stage and boat offices. Lower-class establishments were typically owned and operated by a middle-class family and included a bar room, parlor, kitchen, and bedrooms shared by multiple visitors. In Philadelphia, these simple hotels clustered closest to the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers.

Hotels catering to middle-class guests offered more refined accommodations for lengthier stays and included a lobby, dining rooms, and possibly private, but more likely communal, bathrooms. Improving upon the middle-class model, upper-class hotels offered luxury rooms for writing, smoking, playing billiards, and enjoying nature on rooftop gardens. Luxury hotels also provided entertainment in the form of shopping for the most up-to-date technologies and extravagant merchandise. Middle- and upper-class establishments typically offered two accommodation arrangements: the American and the European plans. While the former charged a fixed rate per day that paid for everything, the latter charged only for lodging.

Perhaps the most renowned early luxury hotel in Philadelphia was the United States Hotel (1828) on Chestnut Street. Although popular and well-visited by celebrities such as Charles Dickens (1812–70), the hotel was quickly surpassed by more technologically updated establishments. The structure was sold to the Bank of Pennsylvania and demolished only thirty years after opening. Nonetheless, Chestnut and Market Streets became popular locations for the majority of middle- and upper-class hotels, with the most elite establishments concentrating around the 700 and 800 blocks of Chestnut. Luxury hotels commonly had important businesses and institutions, such as banks and city offices, as neighbors, confirming the establishments’ centrality not only spatially but also economically and politically.

Nineteenth Century Luxury Hotels

During the middle of the nineteenth century, many of Philadelphia’s luxury hotels, such as the Girard House (1852) and La Pierre (1853), were designed to compete with equivalent establishments in New York City. The Continental Hotel (1860, demolished 1923–24) on Chestnut Street, built on the site of a former museum and circus, was the most revolutionary. Designed by John McArthur, Jr. (1823-90), who later became the architect of Philadelphia’s city hall, the “monster”–scale establishment had six floors with seven hundred rooms that could accommodate up to twelve hundred guests. The elaborate and richly ornamented entrance, completed by Frank Furness (1839–1913) in 1876 in palazzo style, made the hotel one of the most significant architectural sites in the city. The establishment was also notable for its new technologies, such as bell wires and speaking tubes, and steam powered special-purpose machinery, such as a passenger elevator, kitchen equipment, and laundry service. Systems of gas lighting, central heating, air ventilation, and interior plumbing were equally impressive and set a standard for other comparable establishments.

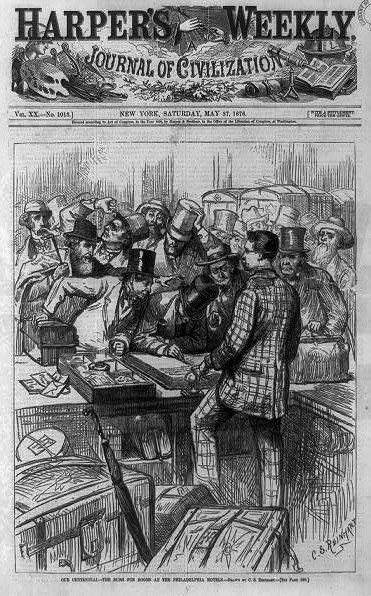

The Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, held in 1876 at Fairmount Park, further spurred the construction of hotels to accommodate large groups of visitors. Six hotels were built at or near the Centennial Grounds: Grand Exposition Hotel, Trans-Continental, United States, Atlas Hotel, Elm Avenue Hotel, and the Globe. The Globe, constructed opposite the entrance to the grounds, contained one thousand rooms to house three to five thousand guests for five dollars a day, up to two dollars more than comparative alternatives. All hotels built for the exposition were demolished soon after its conclusion, except for the United States Hotel, which survived until the 1970s on the west side of Forty-Second Street.

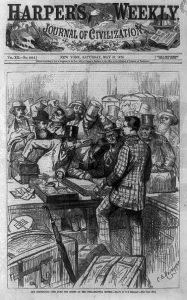

Although the Civil Rights Act of 1875 declared that African Americans were entitled to equal treatment in public accommodations, they were commonly discriminated against and refused service together with other ostracized groups, including Jews. Several of Philadelphia’s hotels were involved in legal cases for violating the law. The Bingham House Hotel (1812) at Eleventh and Market Streets received attention as the first violator when Reverend Fields Cook (1817-97) was denied a room on the basis of his skin color in 1876. Cook took the hotel to court and won, setting a historic precedent. Although African Americans were not always allowed to stay in hotels as guests, their presence was nonetheless continuous as they filled service positions, especially during the white labor shortage brought on by World War I. Their treatment as guests finally improved after World War II as the United States sought to enhance its international reputation by better honoring its claims to the ideals of freedom and equality.

Early Twentieth Century Grand Hotels

The turn of the twentieth century brought important advancements such as iron and later steel construction, innovations in lighting, ventilation, and efficient elevators, all of which made tall hotel buildings feasible. The Divine Lorraine Hotel (1892-03) on North Broad Street was designed by Willis G. Hale (1848-1907), a prominent local architect of luxurious Victorian mansions in Northwest Philadelphia, as a luxury apartment complex but became a hotel after its purchase in 1900 by the Metropolitan Hotel Company. The ten-story building was constructed using a steel frame, hollow brick floors, and brick, stone, and terra cotta exterior walls. Father Divine (1877–1965) acquired the hotel in 1948 and turned it into the first mixed-race hotel in the nation. As North Philadelphia shifted from a prosperous to poverty-stricken area, Divine used his prominence in the area to preach on behalf of equality, desegregation, and anti-lynching legislation.

The Bellevue-Stratford Hotel (1904) at 200 S. Broad Street similarly employed the most advanced construction techniques, using a steel frame for its nineteen stories. Designed by G.W. and W.D. Hewitt (1878–1907), a successful Philadelphia firm specializing in ecclesiastic and residential design, the structure showcased a French Renaissance style. The establishment featured 1,090 guest rooms, an elaborate ballroom, lighting fixtures designed by Thomas Edison (1847-1931), roof gardens open year-round, and even “flush toilets,” among other amenities. The hotel was widely considered to be the most extravagant in the country if not the world, a status reflected in the hotel’s nickname, the Grand Dame of Broad Street. Like other luxury establishments, the hotel also hosted conventions, including prominent social organizations such as the Clover and the Five-O’Clock clubs and other dining groups. Later, the hotel gained notoriety in association with the 1976 convention of the American Legion, during which an outbreak that became known as Legionnaires’ Disease killed twenty-nine convention guests and sickened another 182. The Bellevue-Stratford Hotel was owned and managed by the Capitol Hotel Company of Washington, D.C., which also possessed a chain of luxury hotels connecting Washington, Wilmington, Philadelphia, and New York. This form of nationally coordinated management set a new standard for hotels.

Regional and Resort Hotels

Other parts of the region also attracted substantial hotel investment throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Camden, New Jersey, became a particularly attractive enclave for those aspiring to escape Philadelphia’s religious Blue Laws of 1794, which restricted myriad activities, from sports to the selling of alcohol. Throughout the nineteenth century, Camden’s hotels were intimately connected to the ferry business and thus located close to the Delaware River. For example, the West Jersey Hotel (1850) at Delaware Avenue and Market Street, funded by the West Jersey Ferry Company and designed by Stephen Decatur Button (1813–97) and Joseph C. Hoxie (1814–70), featured metal-frame masonry construction, porches, and a cupola. The establishment closed in 1953 with the discontinuation of ferry service between Camden and Philadelphia.

Hotels also became fixtures in resort towns on the New Jersey shore, which developed rapidly with the construction of ports, roads, and later the Camden-Atlantic City Railway (1852–54), which brought scores of visitors from Philadelphia, Trenton, and Camden. At Cape Island (Cape May), the nation’s first seaside resort town, investors from Philadelphia and New Jersey built the area’s first grand hotel, the Mount Vernon Hotel (1853), near Cape Island Creek. Although never fully completed, the U-shaped structure with raised towers accommodated twenty-one hundred guests in palatial quarters, offering fountains, gardens, stables and carriage houses, tenpin alleys, and pistol galleries. The hotel’s immense dining hall featured more than forty gas-burning chandeliers, which illuminated over 750 people enjoying fanciful meals at any given time. Advertisements for the hotel in local and international newspapers also noted its 125 miles of gas and water pipes, which would have been sufficient to power a moderately sized town. Two fires destroyed the first generation of hotel buildings and only one example survived, the Baltimore Hotel (1867) built on Hughes Street.

In Atlantic City, which formally opened in 1880 and quickly grew to become a major resort destination for celebrities and wealthy Philadelphia residents, one of the most impressive “signature” Atlantic City hotels was the Marlborough-Blenheim Hotel (1902-06, demolished in 1978) at 1900 Pacific Avenue. The structure, the first in the city to be built using reinforced concrete, was designed by Will Price (1861-1916) in the Queen Anne style with Moorish detailing, a stark contrast to other classically-inspired hotels, and featured detailed sculptures of sea horses, seashells, crabs, and seaweed. The architecture suggested that the hotel was a place of sensual pleasure, adventure, extravagance, and fantasy based on pervasive stereotypes of the East and the Orient. Atlantic City suffered a decline in tourism in the mid-twentieth century as a result of increased access to air travel to other vacation destinations and changing leisure patterns. However, with the passing of the 1976 Casino Gambling Referendum, Atlantic City successfully rebranded itself as a tourist site for many different types of entertainment, including gambling.

Hotels in the Post-War Period

Although the Great Depression destroyed much of the hotel business, the outbreak of World War II revitalized the economy and also changed patterns of leisure. Rather than individual luxury hotels, chain establishments and budget hotels came to dominate the hospitality landscape. Chain hotels, the earliest of which were Howard Johnson and Marriott with roots in the restaurant business, offered stability to potential owners fearful of competition. Indeed, chain headquarters equipped their branches with already existing business expertise, technology, equipment, and marketing, while guests enjoyed the consistency of their experience. Budget hotels, which allowed guests to pay only for lodging without additional amenities such as food, television, or telephone, also became a popular option. A number of hotel chains, such as Marriott, Hilton, Sheraton, Holiday Inn, and others located in Philadelphia, and many came to be viewed by city officials as effective instruments for economic redevelopment and urban renewal. For example, the twenty-seven-story Sheraton at Penn Center (1957, demolished in the late 1980s), designed by Perry, Shaw, Hepburn and Dean, was built to include one thousand luxury rooms in the cause of redeveloping the area west of City Hall. Other chain establishments soon followed, including Hilton’s Doubletree in Center City. Midcentury chain hotels shared many visual qualities, including angular form, exposed concrete exteriors, and expansive glass walls.

Midcentury Motels of Greater Philadelphia

Motels emerged in the early twentieth century as an affordable accommodation for a growing middle class with access to automobiles. The new lodging type usually included two twin beds (to better accommodate families), a parking lot, independent access to the room, and a pool. Motels proliferated as a result of the national system of interstate and defense highways begun in 1956, which provided easy access to travel and exploration of America’s cultural and national heritage. Numerous motels were founded near highway exits, thus providing convenient and quick rest stops. The Philadelphia area, as a popular destination for many tourists seeking its attractions related to colonial and American Revolutionary history, served as a hub for many independent and chain motel establishments.

One of the most popular motel chains in the area was the George Washington Lodge, established in 1940 by Philadelphia’s Hankin family. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the Hankins built motels along the newly opened Delaware River Extension of the Pennsylvania Turnpike (1955). Located next to turnpike exits, the lodges offered modern amenities, including indoor and outdoor pools, individually controlled heating and air conditioning, television, and cocktail lounges. The Willow Grove lodge (1963) also included a convention center. Perhaps one of the most visited motels in Philadelphia was the Airport Motel at the Philadelphia International Airport, opened in the 1950s as part of a broader modernization effort. Although rather modest in size with only sixty-seven units before expanding to 150, it included a swimming pool, free television and radios in every room, and access to a “courtesy wagon” shuttle connecting passengers to airport terminals, dining, and other services.

A few motels also opened within Philadelphia’s city limits, although the majority were demolished to make way for denser high-end development. Philadelphia Marriott Motor Hotel (1960s), a 750-room resort complex on City Avenue off the Schuylkill Expressway, featured conference space, indoor-outdoor pools, ten restaurants and lounges, an ice-skating rink, and mini-golf courses. In the Fairmount neighborhood, the Franklin Motor Inn (1959), later Best Western Hotel, was built on land previously occupied by a warehouse complex. The Y-shaped structure was constructed on concrete pillars and included a pool parallel to the parking lot. Due to its central location, many performers from the famous Uptown Theater stayed at the inn after their shows, and according to a 1994 article in the Philadelphia Tribune, Martin Luther King resided at this favored motel on his final visit to the city. The Best Western was demolished in 2014 and replaced by an upscale mixed-use development.

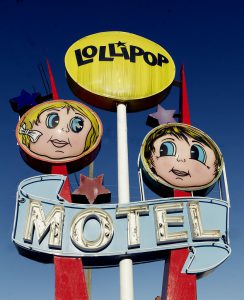

Motels also proliferated in resort towns. In particular, the Wildwoods on the New Jersey shore was a critical region for motel development, remaining into the twenty-first century one of the best-preserved collections of such establishments. After the completion of the Garden State Parkway (1955), the Wildwoods became a popular vacation destination for working- and middle-class families. To attract a modern and youthful clientele, motel owners employed futuristic motifs similar to establishments in Miami Beach and Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Hotels in the Twenty-First Century

Although numerous grand hotels were demolished, especially during the 1950-70s era of urban renewal, remaining structures were commonly repurposed as luxury apartments. For example, after sixteen years of abandonment, the Divine Lorraine Hotel was transformed into luxury apartments in 2017. The $44 million renovation spearheaded by developer Eric Blumenfeld accommodated various functions, including residential units, retail space, and a restaurant on the first floor. The flexible functions of hotels also enabled preservation of distinctive office buildings that had become obsolete for their original purposes. The PSFS Building (1932), which became the Loews Philadelphia Hotel in 2000, was designed by William Lescaze (1896-1969) and George Howe (1886-1955) as the first International Style skyscraper in the United States. However, by the 1980s, businesses were attracted to more modern office spaces and the structure was auctioned to a developer. It was then remodeled by Bower Lewis Thrower Architects (1961–) and preservation consultants starting in 1998 for a hotel to complement the Pennsylvania Convention Center (1993). While the T-shaped tower lent itself well to accommodating hotel rooms, the conversion necessitated the construction of an additional structure for a ballroom and meeting spaces, and the rehabilitation of the original facade.

The evolution of hotel and motel industries paralleled urbanization and trade patterns and responded to the growing popular interest in consumerism, technological innovation, and entertainment. Due to their mission of serving travelers’ contemporary needs, hotels and motels became some of the most rapidly disappearing historic resources in metropolitan regions, commonly demolished to make way for more technologically advanced establishments or other forms of high-density development. Although much of the means of hospitality has changed, the ends of comforting visitors to the the city and region remained, a theme modern promoters of the region exploited to the hilt in describing Philadelphia as “the place that loves you back.”

Vyta Baselice is a Ph.D. student in American Studies/Historic Preservation at the George Washington University, where she studies the intersecting histories of architecture, urbanism, materials, labor, and race. Her dissertation, tentatively titled “Modernizing Magic: Portland Cement and the Material Construction of America,” employs critical theory and ethnographic methodologies to investigate the production and consumption of concrete, and its material effects on built environments and communities. She also holds a master’s degree in architectural history from University College London and a bachelor’s degree in studio arts/architecture from Wesleyan University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- 2010 sets new record for Philadelphia hotels (WHYY, February 19, 2011)

- Philly offers incentives for hotel development (WHYY, July 13, 2011)

- Philly officials hopeful about future of blighted Divine Lorraine (WHYY, October 3, 2012)

- Philadelphia hotels set occupancy record for 2015 (WHYY, December 23, 2015)

- Welcome to Philadelphia-ish: DNC a boon for suburban hotels (WHYY, July 23, 2016)

- Activists question public subsidies used for for North Broad hotel project (PlanPhilly via WHYY, June 12, 2017)

- High-rise hotel coming to site of former Midtown II diner in Center City (PlanPhilly via WHYY, February 20, 2019)

Links

- The Grand Dame of Broad Street (99% Invisible)

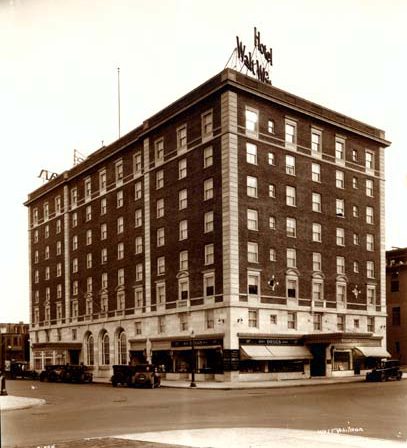

- Staying in Philadelphia: The Hotel Stenton and Hotel Walton (ThePhillyHistory Blog)

- George Washington Motor Lodges: Would George Have Slept Here? (Phila PA Chronicles)

- Echoes of an Extravagant Past: The Ben Franklin House’s Continental History (Curbed Philly)

- The Definitive Guide to Philadelphia’s Historic Hotels (Curbed Philly)

- PhilaPlace: Bingham House Hotel: A Great Transformation (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Step Inside an Old Gothic Hotel of the Atlantic City Boardwalk (Curbed)

- Broad Street’s Original Divine Hotel (HiddenCity Philadelphia)