Infectious Diseases and Epidemics

Essay

Despite Philadelphia’s prominence, throughout its history, as a center for medical education and care, the region has experienced numerous epidemics of infectious disease. British America’s largest city in the eighteenth century, Philadelphia suffered dreadful outbreaks of smallpox and yellow fever, while the nineteenth century brought an exotic new disease—cholera—that killed hundreds. By the early twentieth century, though rates of death from infectious disease remained high by modern standards, scientific advances began to limit their power. Nevertheless, epidemics of influenza, polio, and HIV/AIDS killed thousands through the turn of the twenty-first century even as diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease accounted for an increased share of deaths in the region.

Eighteenth-century Philadelphia was a crossroads of the Atlantic world. Decades before Philadelphia’s founding, the Lenni Lenape suffered near extinction from diseases brought by Swedish and Dutch colonials who built posts along the Delaware River. Philadelphia enjoyed a lower mortality rate than major European cities because of its relative isolation and generally better standard of living, but infectious disease claimed lives daily, and epidemics occurred every year. The region faced threats from three major sources of infection: contamination of food and water with typhoid and other intestinal pathogens; airborne pathogens such as smallpox and measles; and insect vectors carrying diseases, especially malaria and yellow fever, though dengue also circulated in the city.

Smallpox was among the most feared of the infectious diseases. Outbreaks occurred in Philadelphia every year and Philadelphia was probably the only place in the thirteen colonies where smallpox was endemic. The city’s relatively large size enabled the virus to find a continual supply of susceptible individuals. Survivors often bore large, pitted scars and became blind. During the Revolution, smallpox exploded into a general North American epidemic. Philadelphia, occupied by the British, was host to thousands of American prisoners of war, hundreds of whom died of smallpox in indescribably miserable conditions.

While smallpox captured the imagination with its high death rate and gross manifestations on victims’ bodies, less obvious infections claimed even more lives. Eighteenth-century Philadelphians drank water contaminated with fecal matter, which resulted in endemic typhoid, dysentery, and other intestinal diseases. Infants and young children, who were especially susceptible to dehydration, died in large numbers. The young, in particular, also faced threats from scarlet fever, whooping cough, measles, and diphtheria, which was especially dreaded for its ghastly symptoms. In the most virulent cases, a leathery membrane covered large portions of the tonsils and pharynx and killed through slow asphyxiation.

Mosquito-Borne Illnesses

Mosquitos found the region, with its many wetlands, an attractive breeding ground. Though its cold winters discouraged most tropical species from breeding, malaria sickened residents every summer, though most cases were milder than in the southern colonies where the Anopheles mosquito thrived. Dengue, referred to as “break bone” fever because of the excruciating pains that shot through the limbs and backs of sufferers, was also present in the city; the first major epidemic occurred in 1780. The most acute mosquito-borne illness, however, was yellow fever, which ravaged the city sporadically throughout the eighteenth century. The worst epidemic occurred in 1793, brought by ships arriving from the West Indies with infected tropical mosquitoes. By the onset of the first frosts in October, which killed off the mosquitoes, 10 to 15 percent of the city—between four and five thousand people—had died. The epidemic prompted a mass exodus of the city by those who could afford to leave, while those left behind often relied on African American citizens to render assistance and bury the dead.

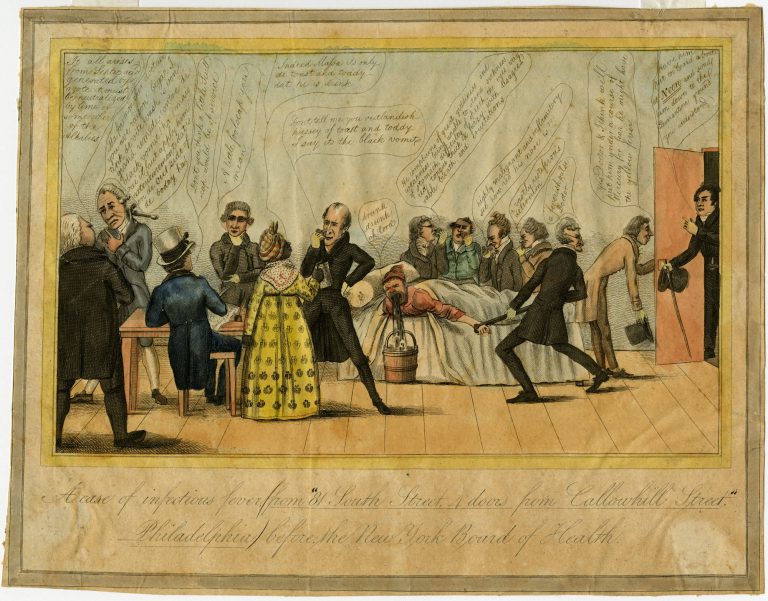

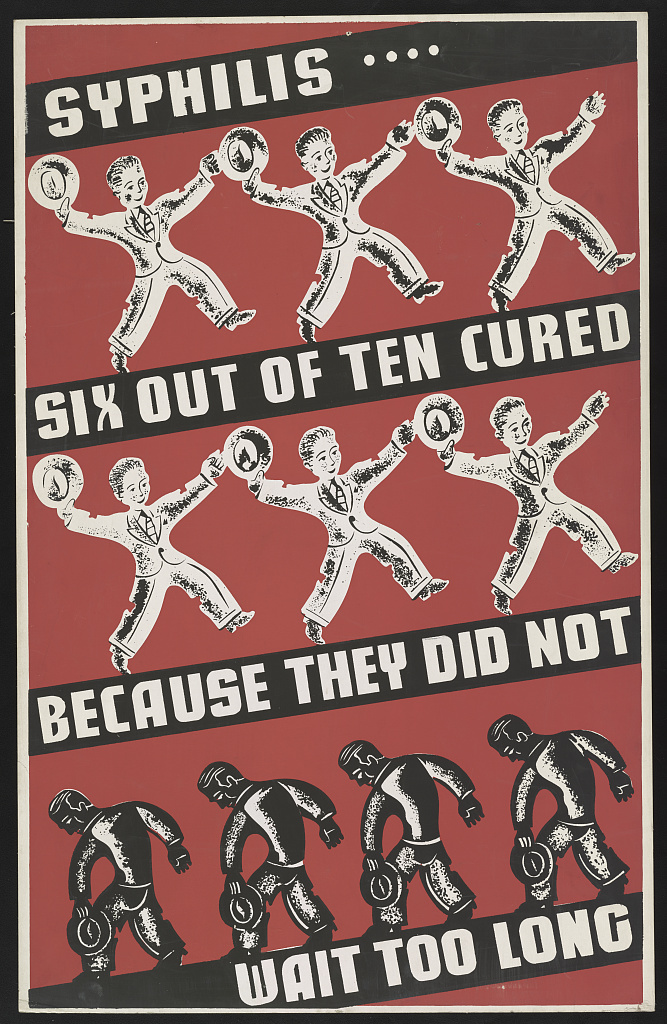

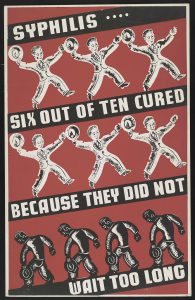

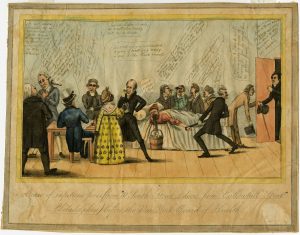

Philadelphia’s high mortality rate from infectious disease during the colonial era revealed a lack of effective treatments. Physicians and surgeons understood a great deal about human anatomy by the middle of the eighteenth century and were able to suture wounds, set fractures, remove decayed teeth, and attend births. But doctors never suspected the causative agents of infectious disease were microscopic organisms. Standard responses to sickness included bleeding; application of caustic plasters to the skin to provoke blistering, which physicians believed would draw out poisons; and induction of vomiting with ipecac or diarrhea with calomel to purge the body. Such interventions often did more to hasten death than speed recovery. To ease pain, quiet a persistent cough, or stem diarrhea, doctors might use opium or laudanum, a tincture of opium and alcohol. For syphilis, which was common in Philadelphia, doctors prescribed doses of mercury high enough to cause symptoms, consistent with heavy-metal poisoning, such as uncontrollable salivation and loosened teeth. Physicians also prescribed less onerous therapies such as dietary and rest regimes.

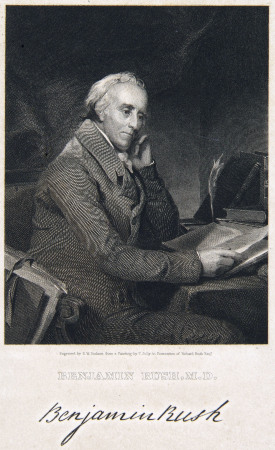

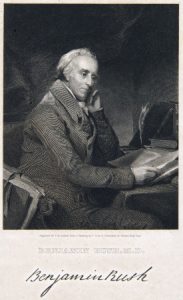

The most impressive weapon against disease was smallpox inoculation, famously championed by Benjamin Franklin (1706–90) after the death of his beloved son in 1736 from the disease. Philadelphia boasted several hospitals, most importantly the Pennsylvania Hospital, the Almshouse (later Philadelphia General Hospital), and the Lazaretto, as well as a growing cadre of physicians, most famously Benjamin Rush (1746–1813), who taught at the nation’s first medical school, at the College of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania), founded in 1765. Two dozen of the city’s leading physicians founded the College of the Physicians of Philadelphia, dedicated to the advancement of medical practice, in 1787.

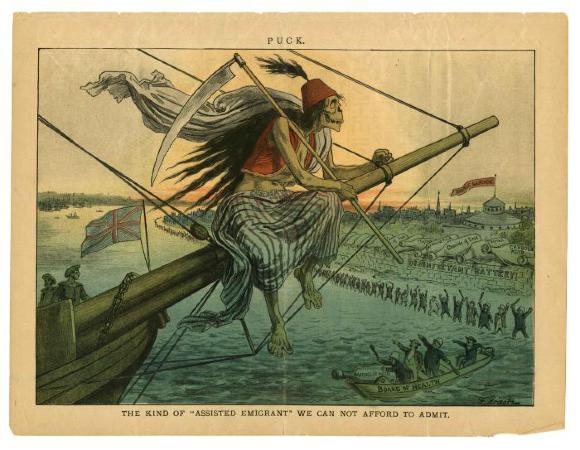

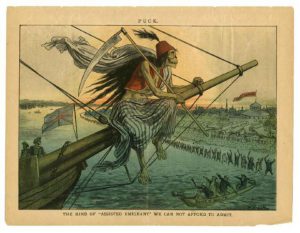

The population of Philadelphia exploded in the nineteenth century. As Philadelphia grew, it drained prodigious quantities of water from surrounding wetlands and diverted or obliterated numerous streams and ponds, decreasing mosquito breeding grounds. The press of people, however, further fouled water supplies. Cholera, a waterborne disease that originated in the Ganges Delta and caused a series of global pandemics, first entered the city in 1832 and killed hundreds. Repeated waves of cholera prompted greater attention to public health in Europe and America and ushered in new thinking about sewage and contagion. Typhus, a highly lethal disease spread by body lice, made its last appearance in Philadelphia in 1893, while smallpox, which state health authorities believed entered the city again with troops returning from the Spanish-American War, caused hundreds of deaths in Philadelphia during the first few years of the twentieth century before vaccination once again brought it under control. Of all infectious diseases, tuberculosis remained the “captain of death,” caused thousands of deaths in the region annually, and motivated the founding of hospitals, clinics, dispensaries, and research organizations.

Scientific Advances Ease Epidemics

Even as infectious disease killed thousands every year, scientific advances offered hope. The bacterial revolution between the 1850s and 1880s, which yielded growing evidence that microbes caused infectious disease, prompted Philadelphia to build the Philadelphia Municipal Hospital for Contagious Disease at Twenty-Second and Lehigh Streets in 1865 to isolate the sick and limit the spread of disease. By the mid-1890s, diphtheria antitoxin began to rescue victims, especially children, from the brink of death. The experiments of Benjamin Franklin Royer (1870-1961), head of the city’s contagious disease hospital, improved the effectiveness of the antitoxin regimen. Royer concluded that physicians should administer massive doses of antitoxin immediately when they suspected diphtheria, even before laboratory confirmation of the disease. Physicians across the country heeded Royer’s recommendations.

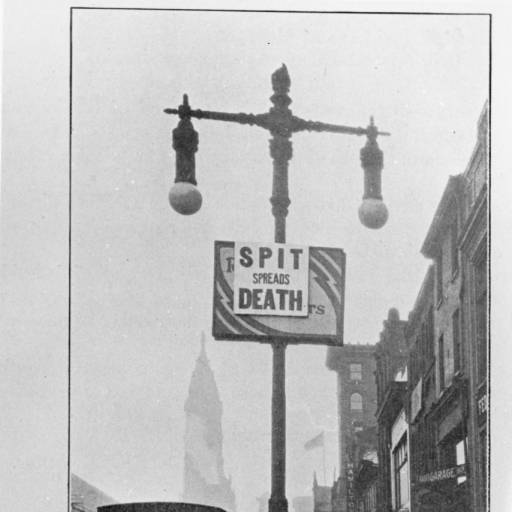

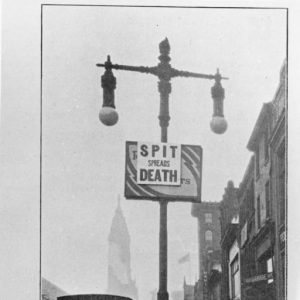

By World War I, Philadelphia filtered and chlorinated its water supply and watched as mortality from waterborne disease shrank to low background levels. Insect-vectored diseases, too, no longer posed a serious threat. Though most infectious diseases could not yet be cured, recognition of the importance of patient isolation, quarantine, cleanliness, and hygiene, along with increased access to hospitals and doctors all combined to reduce deaths from contagious disease.

Still, in 1916, Philadelphia’s first major outbreak of polio sickened hundreds and paralyzed or weakened scores. Even more terrible than this specter of paralyzed and dying children was the influenza epidemic that raged across the world and emerged in Philadelphia in September 1918, the city’s first major epidemic since cholera, killing between thirteen thousand and nineteenth thousand people by March 1919. Philadelphia experienced the worst urban outbreak in the nation because the first appearance of the virus in the city coincided with a war bonds parade; the large crowds in attendance permitted the virus to infect thousands in one day, and tens of thousands within the next week. The large number of rapid deaths overwhelmed city services, with corpses languishing in apartments and mass burials the result.

Like the rest of the nation, however, Philadelphia entered the 1920s relatively free of infectious disease. Deaths from what are now vaccine-preventable diseases occurred at a much higher rate than they would a century later, but were a rarity compared to the rates experienced just a generation previous. The drop in mortality resulted mainly from public health measures that limited exposure to serious infectious disease, as well as from improved medical care. In the late 1930s, the first class of antibiotics—sulfa drugs—became available. A decade later, the introduction of penicillin, along with the rapid development of other antibiotics, led to the marked diminishment of bacterial infections, while the rapid introduction of vaccinations for diphtheria, mumps, whooping cough (pertussis), measles, polio, influenza, and tetanus further reduced sickness and mortality from infectious diseases. With the exception of polio and the influenza epidemics in 1957 and 1968, infectious disease ceased to be an important cause of death on the region’s component of mid-to-late-twentieth century mortality rolls.

Legionnaires’ Disease, 1976

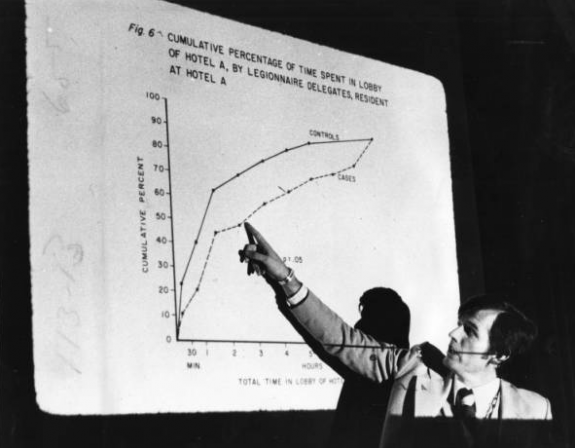

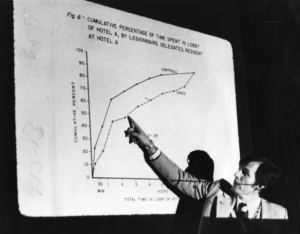

The hiatus from outbreaks ended, however, in 1976, when attendees of a convention of the American Legion in Philadelphia complained of weakness, fever, and shortness of breath. In little more than a week, more than two hundred convention-goers sickened and thirty-two died. The pathogen, a species of bacteria never linked to human illness, was named Legionnaires’ disease and forever linked to Philadelphia.

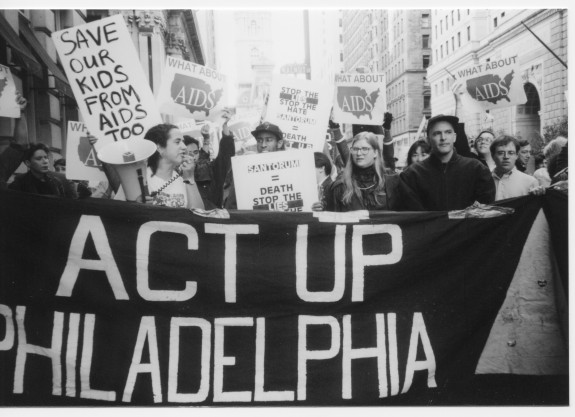

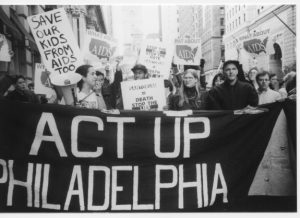

As the Legionnaires’ outbreak splashed across the headlines, another infectious killer stalked the city; by the mid- to late 1970s, the human immunodeficiency virus began its infiltration of Philadelphia, especially among the city’s intravenous drug users and gay men. By 1980, heterosexuals, too, especially hemophiliacs and those under age thirty, came into increasingly frequent contact with the virus. Deaths must have occurred, but because they were few and occurred in marginalized populations with limited access to medical care, they were missed. By September 1981, however, Philadelphia physicians diagnosed patients whose symptoms were consistent with those seen in the first reported cases in Los Angeles and New York a few months earlier. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, Philadelphia fought a rising tide of illness and deaths. Until the advent of retroviral treatment in 1996, Philadelphia relied on two classic principles of public health, isolation and prevention, to slow the virus’s destruction.

With the exception of HIV, infectious disease—though it always posed a threat—failed to produce a major, high-mortality outbreak, let alone a citywide epidemic. One national study of mortality from infectious disease, applicable to Philadelphia, found that between 1900 and 1996, mortality from infectious disease decreased from 797 deaths per 100,000 of the population in 1900 to only 36 per 100,000 in 1980. The AIDS epidemic and increased deaths from influenza and pneumonia among the elderly increased the rate to 59 per 100,000 by 1996, but this was still less than 10 percent of the rate a century earlier. As deaths from infectious disease declined, cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s claimed a greater percentage of lives and became the major killers in the region.

Founded during the early modern era of medicine, Philadelphia and the surrounding region partook in and contributed to the sweeping changes in our understanding of disease during the nineteenth century—and remained on the cutting edge of research and treatment into the twenty-first century. Few major episodes in American medicine failed to touch the region and its people, while the work of the area’s physicians, nurses, engineers, and researchers improved the lives of people across the globe.

James Higgins is a lecturer in American history at the University of Houston–Victoria. He specializes in the history of medicine, especially as it pertains to Pennsylvania. His manuscript, which analyzes four urban outbreaks in Pennsylvania during the 1918–19 influenza pandemic, is with the University of Rochester Press. He has offered a dozen conference papers and several articles, invited lectures, and book chapters. (Author information current at time of publication).

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Real-life disease trackers are on the job (WHYY, October 4, 2011)

- 30 years into AIDS epidemic advocates say financial resources are diminishing (WHYY, December 1, 2011)

- Delaware health leaders warn of mosquito-borne disease (WHYY, July 22, 2014)

- Seventh-graders mix history, literature in study of Philadelphia's 1793 yellow fever epidemic (WHYY, March 4, 2015)

- University employee tests positive for Legionnaires' disease (WHYY, July 30 2015)

- In wake of alarming HIV forecast, Philadelphia intensifies new approach to curb epidemic (WHYY, March 23, 2016)

- Preservation of the Lazaretto, America's oldest surviving quarantine center, finally gets underway (WHYY, October 31, 2016)

Links

- Philadelphia Under Seige: The Yellow Fever of 1793 (Pennsylvania Center for the Book, Pennsylvania State University)

- The Yellow Fever Epidemic in Philadelphia (Harvard University Open Collections)

- What the Doctor Ordered: Dr. Benjamin Rush Responds to Yellow Fever (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- History of the Pennsylvania Hospital (University of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: The College of Physicians (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- 1918: Death on the Home Front (Philly History Blog)

- Lazaretto Quarantine Station Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- PhilaPlace: The Fairmount Water Works — Disease and the City’s Water Supply (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Kill the Rats! (Philly History Blog)

- “The Philly Killer:” 1976’s Legionnaires’ Disease (Pennsylvania Center for the Book, Pennsylvania State University)

- Bacteria And The Bellevue: The Birthplace Of Legionnaires’ Disease (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- City of Philadelphia AIDS Research and Data (Phila.gov)