Jewelers Row

Essay

Jewelers Row in Center City Philadelphia emerged in the 1880s and over time became home to more than two hundred jewelry retailers, wholesalers, and craftsmen. Many of these businesses were owned by the same families for generations. By the twenty-first century, Jewelers Row had become regarded as the oldest diamond district in the United States, second in size only to the jewelry district in New York City. Located within the East Center City Commercial Historic District, Jewelers Row embodied Philadelphia’s commercial legacy, linking small-scale, family-owned manufacturing businesses with the city’s well-established financial institutions and a retail industry synonymous with quality merchandise.

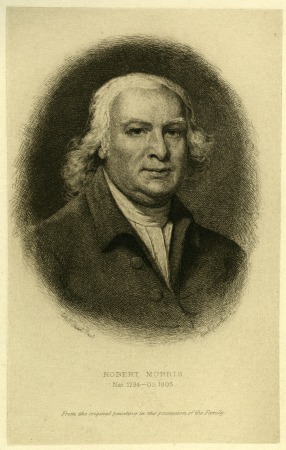

Situated in the heart of the original city plan for Philadelphia, on Sansom Street between Seventh and Eighth Streets and on Eighth Street between Chestnut and Walnut Streets, Jewelers Row reflected the architectural and developmental history of the city. These blocks were originally laid out by William Penn (1644-1718) and his surveyor general, Thomas Holme (1624-95). Following Penn’s death in 1718, his son Thomas Penn (1702-75) sold the land in 1726 to Isaac Norris Sr. (1671-1735), a prominent merchant and statesman. The property remained in the Norris family for much of the eighteenth century, until its sale in 1791 to merchant and financier Robert Morris (1734-1806). In 1794, Morris began construction of a mansion, designed by the French-born architect and civil engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant (1754-1825), on his newly acquired Chestnut Street lot. However, between the expenses incurred during the American Revolution and a series of failed investments in land speculation, Morris fell into bankruptcy, and his unfinished mansion became known as “Morris’s Folly.”

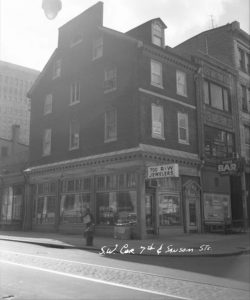

After the city government confiscated the land to pay Morris’s debts, in 1798 the block of Walnut Street from Seventh to Eighth Streets was purchased in a sheriff’s sale by the Quaker philanthropist and real estate developer William Sansom (1763-1840). He tore down the mansion and bisected the property with an eponymous east-west street. He contracted with Benjamin Latrobe (1764-1820) to construct speculative housing on the north side of Walnut Street, while the Scottish architect Thomas Carstairs (1759?-1830) was hired to construct housing on the south side of the newly developed Sansom Street. Between 1800 and 1802, Carstairs proceeded to build a block-long series of twenty-two identical Georgian-style row houses known as Carstairs Row, modeled after earlier patterns of row houses constructed in the squares of London, Bath, and Dublin. To attract tenants to this relatively undeveloped area of the city, Sansom paved the street at his own expense.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, increasing industrial and commercial development, spanning an area from Walnut Street in the south to Arch Street in the north, spurred interest in creating new residential districts. Following the consolidation of the city with Philadelphia County in 1854, the city’s wealthier residents moved westward to the more fashionable Rittenhouse Square and new neighborhoods across the Schuylkill River in West Philadelphia. The row houses they left behind in older and increasingly working-class and ethnic neighborhoods became available for commercial uses. The Chestnut and Market neighborhoods became major intersections for horse car, omnibus, and later electric trolley routes from West Philadelphia and Rittenhouse, linking wealthy Philadelphians to the city’s retail and financial institutions.

Before it became a jewelry district in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the 700 block of Sansom Street was the center of a thriving engraving trade, which benefited from its proximity to an established printing industry, including many publishing firms on Sansom Street or nearby on Chestnut Street. The engraving business, with its high level of technical expertise and precision, formed a natural relationship with jewelry and watchmaking crafters and suppliers, who used a similar set of skills and tools. Over time, independent engravers continued to prosper due to the booming publishing industry, but they did not increase in number. Meanwhile, scores of diamond wholesalers, setters, crafters, lapidaries, and similar luxury industries moved onto the Row, bolstered by several waves of Eastern European and Jewish immigrants who settled in Philadelphia between the 1880s and early 1900s. For example, about a dozen engravers plied their trade on the 700 block of Sansom between 1879 and 1908. At the same time, the number of jewelry and diamond sellers and manufacturers exploded from five to more than seventy-five and eventually surpassed two hundred establishments by 1930.

As the jewelry industry flourished, architectural alterations changed the look of the Row, with out-of-fashion Georgian exteriors replaced by in-vogue Victorian styles. More businesses relocated from elsewhere in the city, resulting in the Philadelphia jewelry industry becoming increasingly centered upon the Row. Although prominent jewelry retailers such as Biddle and Co. continued to operate elsewhere, in the early twentieth century more than 50 percent of diamond dealers and more than 80 percent of diamond setters and cutters worked on the Row. Dubbed Jewelers Row in commercial advertisements and local media by at least the late 1910s, the area’s reputation as the locus of Philadelphia jewelry-making was further cemented over the next several decades, culminating in the construction of the Art Deco Jewelry Trades Building on the west end of the 700 block of Sansom Street in 1929.

Unlike other local industries, such as styled-textile manufacturing, a combination of factors made Jewelers Row well suited to survive through periods of economic distress and market volatility. Despite cyclical periods of stagnation and contraction, skilled jewelry craftsmen enjoyed a path to proprietorship that was relatively easy and more economical when compared to other industries that relied on rapid technological advances to thrive. At the same time, unlike larger markets such as New York City, Philadelphia’s smaller size allowed the luxury industry to better combat over-competition or product oversaturation. Being structurally and functionally divided among final goods makers, component suppliers, and ancillary specialists also benefited Philadelphia jewelers, as it both prevented assimilation by larger predatory entities and avoided disruption during periods of labor activism, while the relatively localized market limited interregional competition. Moreover, Philadelphia’s reputation as a thriving and fertile marketplace facilitated the rise of jewelry wholesalers on the Row who redistributed seasonally styled goods to both smaller shops and larger retail outlets. Finally, the presence of established family-owned firms and a deeply rooted Jewish community ensured a strong sense of loyalty among customers who prized Jewelers Row for its imaginative designs and quality craftsmanship.

Once established as Jewelers Row, the various traders and artisans fought to uphold the district’s reputation while also competing with larger regionalized retailers. Throughout the early twentieth century, merchants feared losing business to outside the Row. The Sansom Street Business Men’s Association formed in 1913 to advance the interests of local shopkeepers and even employed detectives to deter crime. These concerns became increasingly strident over the latter half of the century as suburbanization resulted in a decrease in commercial traffic to Center City businesses. Particularly detrimental to downtown business districts such as Jewelers Row, new shopping malls on the periphery offered many of the amenities and services that had previously attracted consumers to the downtown, but without the burdensome commute. To combat this, local jewelers leveraged their district’s storied heritage, forming the Jewelers Row Association in 1986 as a cooperative effort to compete with suburban jewelry retailers by enhancing the visibility, reputation for quality, and aesthetic appeal of the Sansom Street properties.

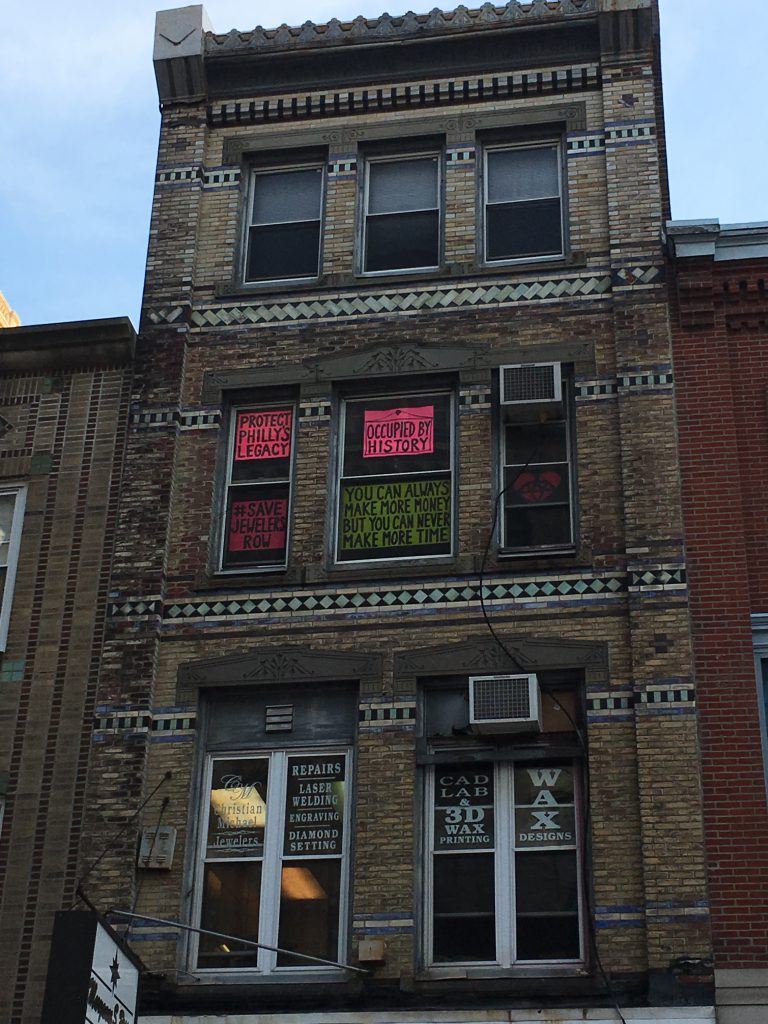

In 2016, Jewelers Row became the focus of public attention when a proposed redevelopment of part of the 700 block of Sansom Street by Toll Brothers sought to demolish and replace several of the buildings with a high-rise condominium. Some of the local businesses and historic preservationists resisted the plan, which developers argued would revitalize the area by attracting new, middle-class residents and also bring much-needed revenue to the city through property taxes. Opponents fought to protect the architectural heritage of the block by nominating three of the five buildings proposed for demolition (704 and 706-708 Sansom Street) to be designated as historic structures by the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places, joining several other addresses on the Row that already possessed landmark status. The battle reflected the complex identity of Jewelers Row itself: a mix of old-world craftsmanship, family-owned businesses, and architectural history, combined with modern concerns of urban decentralization, changing demographics, and privatized development in a city looking to the future while at the same time seeking to preserve the legacy of its past.

Lance R. Eisenhower is a doctoral student in American history at Lehigh University and holds an M.A. in history from Villanova University. He is a Lecturer of History at Montgomery County Community College. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Demo plans for Philadelphia's Jewelers Row losing sparkle (WHYY, August 20, 2016)

- Past mistake: Preservationists hope city will learn from Jewelers' Row threat (PlanPhilly, August 23, 2016)

- Frustration, opposition from Jewelers’ Row at community meeting on Toll Bros. plan (PlanPhilly, August 24, 2016)

- Support for preservation-minded solutions at Jewelers' Row (PlanPhilly, September 28, 2016)

- Committee supports designation of two threatened Jewelers' Row buildings (PlanPhilly, October 21, 2016)

- Renderings of Jewelers' Row tower presented to Washington Square West (PlanPhilly, January 24, 2017)

- Demolition permits issued for Jewelers' Row buildings (PlanPhilly, November 9, 2016)

Links

- Community Meeting Reveals Widespread Indignation With Jewelers Row Demolition (Hidden City)

- On Jewelers Row, Tracing The Origins of 702-710 Sansom Street (Hidden City)

- On Jewelers Row, Oral History Project Goes Beyond The Bench Work (Hidden City)

- Kenney “Frustrated” With Jewelers Row Preservation Saga (Hidden City)

- Committee Recommends Jewelers Row Buildings For Designation (Hidden City)

- Permit And Postponement Put Jewelers Row In Urgent Jeopardy (Hidden City)

- Toll Bros. Render Grim Future For Historic Properties On Jewelers Row (Hidden City)

- Jewelers Row Attraction Details (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Carstairs Row (Philadelpia History Blog)