Lancaster Avenue

Essay

Extending through West Philadelphia into Philadelphia’s western suburbs, Lancaster Avenue has defined a corridor for commerce and community development from the colonial era to the twenty-first century. Named for its destination city more than sixty-five miles away from its origin near Thirty-Second and Market Streets in Philadelphia, the road also memorializes the important commercial, social, and political interactions between Philadelphia and Lancaster during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Pennsylvania founder William Penn (1644-1718) authorized a road extending west from his port city to the interior in 1697, but like many colonial-era roads at that time it remained little more than a tramped-over expansion of earlier Indian trails that traversed the region. Impetus for improving the road gained strength as settlers, primarily Germans, moved into the far reaches of Chester County near the Susquehanna River—the area designated as Lancaster County in 1729. In addition to moving agricultural goods to market, during the eighteenth century the roadway became known as the “Great Wagon Road” as it enabled thousands of migrants to move into the backcountry of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina.

A Commercial Lifeline

The Philadelphia-Lancaster Road supported increasing ties between Philadelphia and the new county seat town of Lancaster. Founded in 1729, Lancaster originated as a proprietorship of prominent Philadelphia lawyer Andrew Hamilton (c. 1676-1741), who then served as Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly, and his son James (1710-83), also a lawyer and future lieutenant governor of Pennsylvania. The elder Hamilton laid out Lancaster in the image of Philadelphia, with a central square for public buildings and a grid plan of streets. The new town site had an unusual location away from major waterways, but it benefited from the Philadelphia-Lancaster Road, which as King Street ran straight through the middle of town. As Lancaster grew, its merchants ordered goods from Philadelphia and formed partnerships with Philadelphia enterprises; the merchandise hauled by wagon to Lancaster served not only the townspeople but also nearby communities in Pennsylvania and the population spreading into the southern backcountry. As a market town, Lancaster served as a point of exchange for the agricultural production of an extensive hinterland. People, freight, crops, and animals all moved on the Philadelphia-Lancaster Road between the interior and Pennsylvania’s major port in Philadelphia. The road also made Lancaster a natural choice for refugees from Philadelphia during the British Occupation of 1777-78, and it facilitated the movement of the Continental Congress to temporary quarters in nearby York.

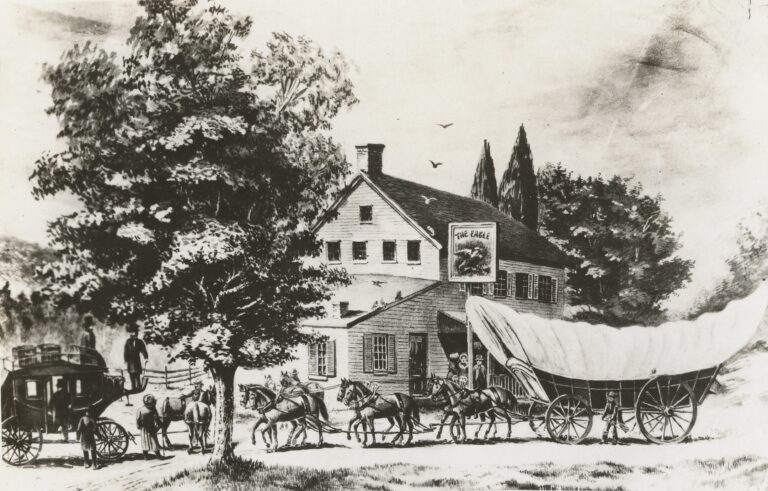

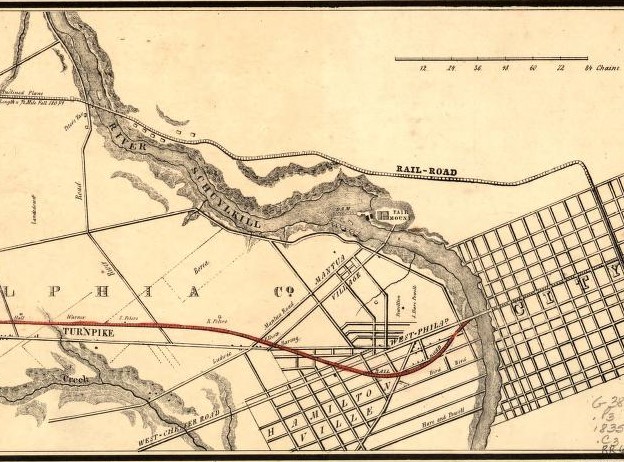

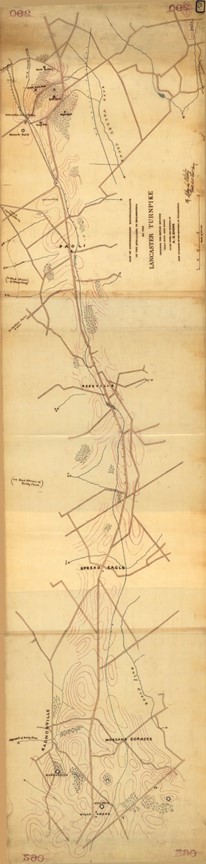

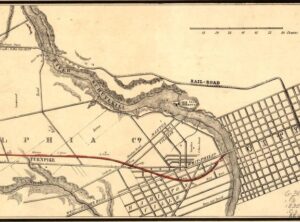

In 1795, the Philadelphia-Lancaster Road became the first turnpike in the United States, which led to improvements such as crushed-stone pavement, widening and straightening, and improved drainage for all-weather travel. Inns and taverns opened at close intervals along the improved route, and stagecoach services contributed to the growth of towns between Philadelphia and Lancaster, including Downingtown and Coatesville in Chester County. For Philadelphia, Lancaster Pike—together with Market Street, Baltimore Pike, and Darby Road—enabled trade and travel from the Pennsylvania hinterland to the ferries and bridges that crossed the Schuylkill River into the city. (Prior to the Consolidation Act of 1854, the city limits did not extend west of the Schuylkill.)

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Lancaster Avenue evolved as a commercial spine for adjacent neighborhoods in West Philadelphia and towns in the city’s western suburbs. Transportation helped to spur new development. During the 1830s, the Philadelphia and Columbia Railway ran parallel to the Lancaster Pike; after acquisition by the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1850, this “Main Line” became a corridor for development of suburban estates for the wealthy. (More modest homes closest to Lancaster Pike accommodated business proprietors and staff for the estates.) Within West Philadelphia, horse-drawn omnibuses for commuters began to travel Lancaster Pike in 1858 with the founding of the Hestonville, Mantua, and Fairmount Horse Car Passenger Railway. The horse cars enabled commuting between central Philadelphia and developing neighborhoods such as Powelton, Mantua, and Hestonville (at Lancaster and Fifty-Second Street). Lancaster Pike in West Philadelphia became lined with two- and three-story brick buildings, most of them commercial enterprises.

Hospitals, Churches, Schools

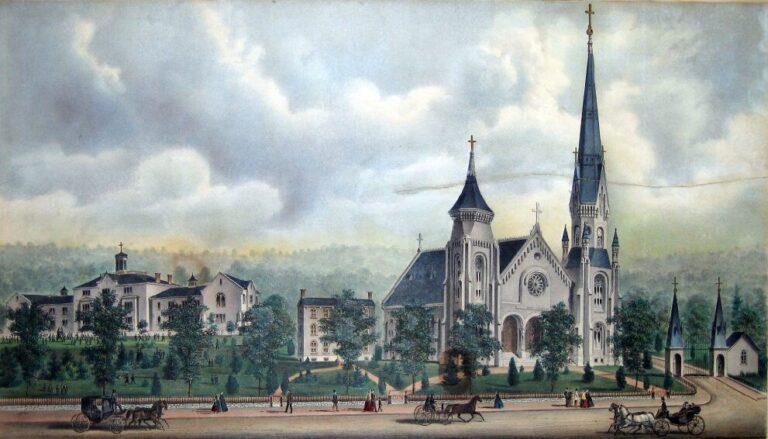

Transportation also made Lancaster Pike a prime location for institutions and organizations founded during the nineteenth century, among them the Rush Hospital for Consumption, the Presbyterian Hospital, the Blind Women’s Home, and the Industrial Home for the Working Blind. Religious institutions included a Hicksite Quaker Meeting House and a cluster of Gothic-revival churches in Overbrook, which developed in the 1890s adjacent to the city’s western boundary. In the suburbs, colleges and universities with Lancaster Pike (or Avenue) addresses included Haverford College, founded by Quakers as a men’s college in 1833, and Villanova University, founded for Roman Catholic men in 1842.

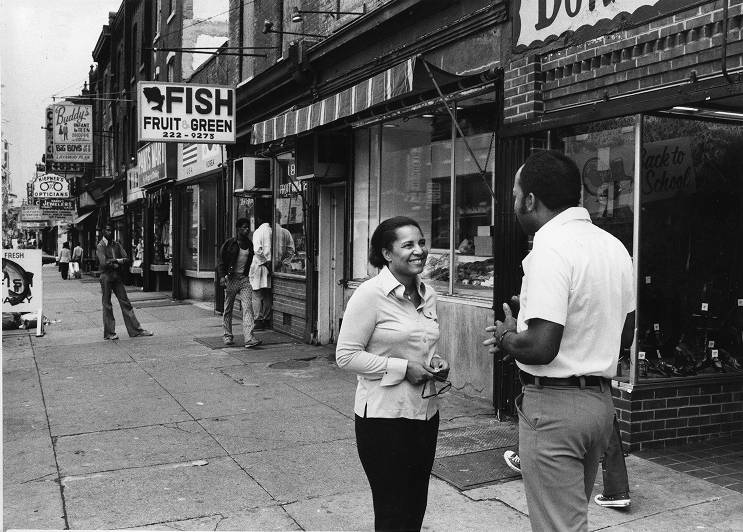

In the early twentieth century, Lancaster Avenue within Philadelphia became an important center for African American commerce as the Great Migration from the South added to the Black population of West Philadelphia. Shoppers could patronize Black-owned and white-owned furniture stores, markets, pharmacies, and more. Amid the business activity, Black Muslims established a presence on Lancaster Avenue during the 1950s and 1960s, and Muhammad’s Temple of Islam #12 relocated from North Philadelphia to 4218 Lancaster Avenue in 1957. The temple’s teachers and administrators included Malcolm X (1925-65) and Imam Warith Deen (Wallace D.) Muhammed (1933-2008). Lancaster Avenue’s centrality for Black Philadelphians led to a visit by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-68), who spoke at a massive rally at Fortieth Street and Lancaster Avenue in 1965 during his Freedom Now campaign.

The road between Philadelphia and Lancaster gained additional attention and significance in 1913, when it became part of the coast-to-coast Lincoln Highway (later designated U.S. 30). But as a commercial corridor, Lancaster Avenue reflected the fortunes of adjacent neighborhoods. In West Philadelphia, decline and disinvestment on the avenue can be traced to practices of the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), which created long-lasting stigmas of racial, ethnic, and class inequality with its 1937 maps of neighborhood characteristics. The HOLC included Lancaster Avenue between Thirty-Second and Thirty-Seventh Street in a zone north of Market Street deemed “hazardous” (redlined) on the basis of obsolete properties, the “concentration of Negroes and Italians,” and the large number of families on relief during the Great Depression. The designation contributed to the area’s decline by branding it a bad risk for mortgage lenders. Neighborhoods farther west fared better in the HOLC surveys, but only Overbrook adjacent to the western city limit received the highest ranking of “best.” There, the surveyors found a restricted neighborhood with no immigrants or African Americans; they predicted desirability for the next ten to fifteen years but noted part of the area as “threatened with Italian expansion.”

Urban Renewal Zones

The HOLC judgments set the stage for later urban renewal demolitions and, by the twenty-first century, redevelopment projects and plans. During the 1950s and 1960s, three urban renewal zones included portions of Lancaster Avenue in Philadelphia: one for the northward expansion of Drexel University (overlaying Lancaster Avenue between Thirty-Third and Thirty-Fourth Streets); another to create the University City Science Center and University City High School (with Lancaster Avenue as its northern boundary between Thirty-Fourth and Thirty-Eighth Streets); and a third for construction of public housing (impacting Lancaster Avenue between Forty-Fourth and Fifty-Second Streets). Demolitions and displacements contributed to a decline in population that drained economic vitality from many Lancaster Avenue businesses, leaving many buildings from more prosperous times vacant and deteriorating.

From the 1960s through the 2020s, attention to redeveloping Lancaster Avenue and nearby neighborhoods arose from adjacent communities, city planning agencies, private developers, and universities. Turning away from the urban renewal strategies of demolition, community-engaged planning led to revitalization projects such as murals reflecting community history, street-cleaning, façade improvements, and initiatives to attract new businesses. Attention to public spaces included a monument at Fortieth and Lancaster Avenue to commemorate the speech given there by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Although far less active than its height in the early twentieth century, Lancaster Avenue retained a core of small businesses, especially between Fortieth and Forty-Second Streets. To the southeast, at Thirty-Sixth Street, a partnership including Drexel University anchored the eastern segment of the avenue with a building for life science companies called UCity Square, opened in 2023. The university’s expansion and private developers’ interest in building market-rate housing for students grew to the point that neighbors in Powelton mobilized to protect historic buildings; they included most of Lancaster Avenue between Thirty-Fourth and Fortieth Street in their nomination of the Powelton Village Historic District, which was added to the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places in 2022.

Although much changed from its origins as an Indian trail and dirt road between Philadelphia and Lancaster, Lancaster Avenue (or Lancaster Pike) remained the roadway’s local street name in Philadelphia and the western suburbs. In the early twenty-first century, a diagonal walkway through the campus of Drexel University marked the point of origin for the historic highway, which reached westward through businesses and rowhouses in West Philadelphia, into the western suburbs and countryside, to reach its destination city of Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Charlene Mires is Professor Emerita of History at Rutgers University-Camden and formerly Editor-in-Chief of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2024, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- Lancaster Avenue

- Lancaster Avenue Business Association

- Lancaster Avenue Project

- Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Road (ExplorePAhistory.com)

- Powelton Village Historic District

- Ardmore: The Main Street of the Main Line

- Lower Lancaster Revitalization Plan (PDF)

- U.S. 30 (Lancaster Avenue) Corridor Study: Creating Linkages and Connecting Communities (PDF, Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission)

- Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor