Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

By Mabel Rosenheck | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

In 1805, a group of artists and elite Philadelphians founded the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts as the first institution in the United States to operate as both an art museum and an art school. Throughout its history, the academy maintained two distinct reputations. On the one hand, it was a collecting and exhibiting institution that maintained a conservative emphasis on eighteenth and nineteenth century American art. On the other, it was a school where students and faculty were just as likely to work in newer, more innovative styles. By the twenty-first century, these two aspects of the institution came together in new ways as the academy’s Victorian-era building on Broad Street housed dramatic exhibitions of modernist and contemporary art that highlighted work by women and people of color alongside its well-known canonical masterpieces and lesser-known acquisitions. This approach revealed a collection that—like the institution as a whole—had in fact long been more dynamic than it seemed.

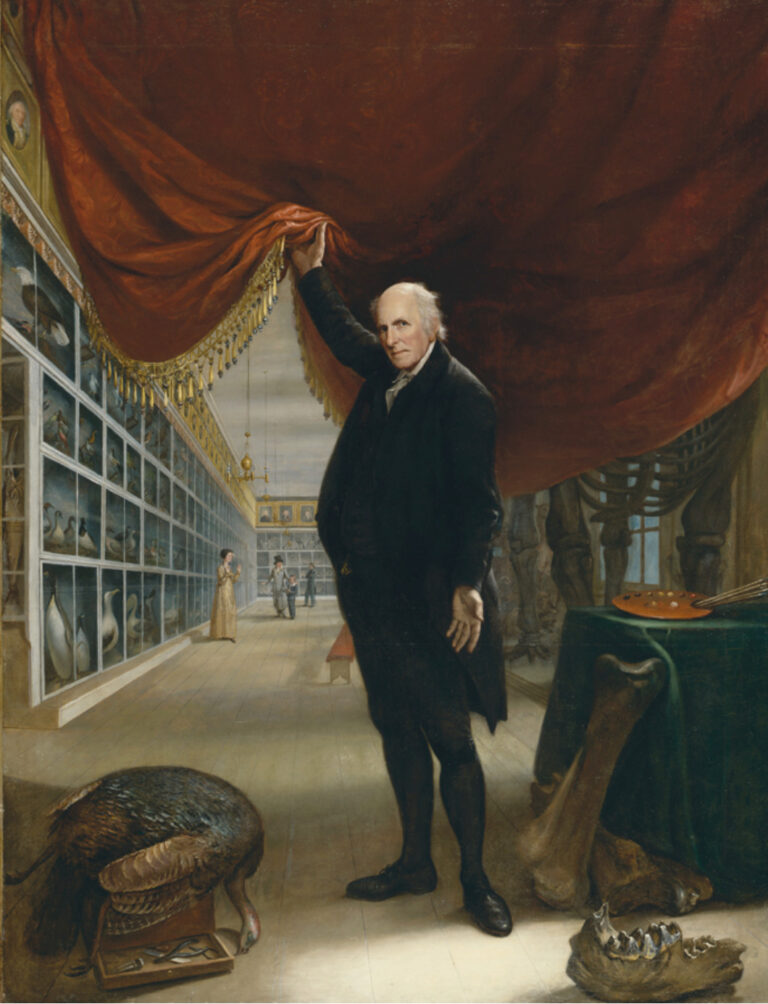

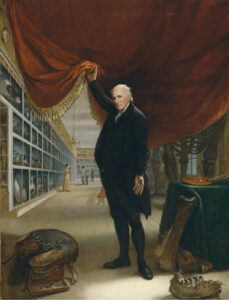

The founding of the academy followed the short-lived Columbianum, a fine art institution created in 1794 by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) as a place for artists, owned by artists, where they could learn painting and drawing technique and could exhibit and sell their work. Due to infighting, the Columbianum only lasted a year. At stake was the administration and funding of the organization as well as the very worthiness of art and art patronage in the New Republic. A decade later when Peale and others founded the academy, the needs for training and patronage that Peale identified were still unmet. Together with Peale, the academy’s 112 founding subscribers included two other artists—his son Rembrandt Peale (1778-1860) and sculptor William Rush (1756-1833)—and a larger group of elite professionals. The artists wanted the new organization to serve as an educational institution and exhibition space. The rest were at least as interested in using the museum to display emerging American taste.

Like the Columbianum, the academy emerged amid a debate over the place of art in the New Republic. Some were concerned that art and an art market would be a force for moral corruption stemming from ostentatious wealth and materialism. Peale, however, was one among many of the academy’s founders who argued that art could foster civic virtue and construct a national identity through portraits of great American men and great American landscapes. Still, noble as their stated interests were, the academy’s founders, especially those who were not artists themselves, also employed art as a display of wealth, using taste to demonstrate the refined identity of America and their personal elite status.

Memberships Began at $50

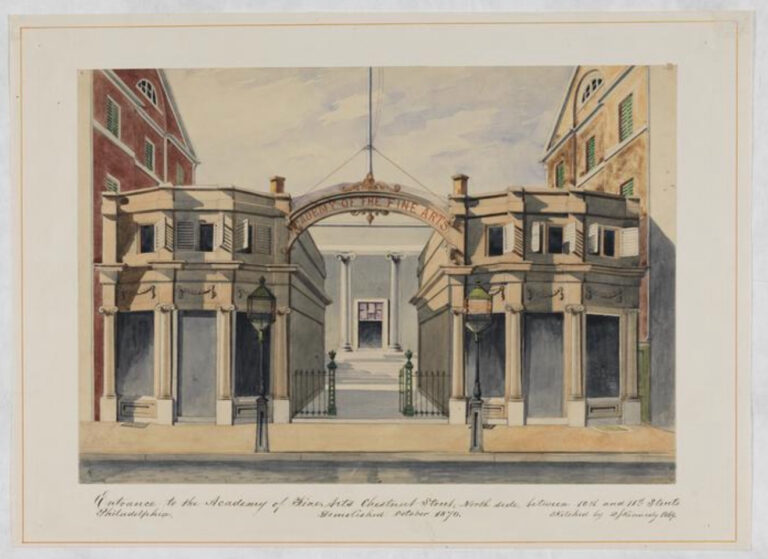

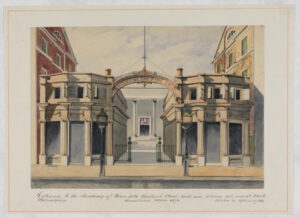

The academy, which first resided in a neoclassical building on Chestnut Street between Tenth and Eleventh, was originally funded by patrons and members who were stockholders in the institution. Membership granted votes for decision-making as well as access to the collections, and they began at $50. The high price indicates that the academy initially served as a social club as much as a training ground for artists. In 1810, however, a group of Philadelphia artists formed the Society of Artists of the United States and pushed for the academy to realize Peale’s original goals alongside those of the stockholders. As a result, in 1811 the academy began annual exhibitions to showcase work to buyers, and the following year created the Pennsylvania Academicians—artists who were granted the privileges of stockholders without having to pay the fee.

The collections began with copies and casts of European masterworks. At the time, no museums or even private individuals in the United States owned the original works, so copies served to connect artists and elites with European traditions and to legitimate Americans as part of a lineage of Western art. For over a century—even after that kind of training fell out of fashion—the casts remained central to the academy’s curriculum which focused on the anatomy of the human form and the technique necessary for realist drawing and painting. As the academy collected casts, it also acquired work that used the techniques being taught. This included portraits of prominent Americans like George Washington in the Landsdowne Portrait painted by Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828), a portrait of artist Benjamin West (1738-1820) painted by Thomas Sully (1783-1872), and others painted by—or of—various members of the Peale family. The early collections also included epic history paintings like The Dead Man Restored to Life by Touching the Bones of the Prophet Elisha by Washington Allston (1779-1843) and Death on a Pale Horse by West. These dramatic, narrative works were put on display in part to attract the attention of the paying public.

While some instruction began after the challenge by the Society of Artists, a formal curriculum did not emerge until 1856. By this point, life drawing had become as important as drawing from the casts, and it quickly became controversial, particularly in the education of women. Women had trained at the academy from its inception, but they were only permitted to draw from the casts if a fig leaf covered the genitalia, and they were not permitted to take life classes at all. In 1860, Eliza Haldeman (1843-1910) and Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) began independent sessions where female students modeled for one another, and by 1879, they forced the academy to allow live models in their classes. Nevertheless, in 1886 when Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) removed the loin cloth from a male model while teaching a women’s class, the action was viewed as a violation of norms of moral respectability and led to his dismissal from the academy. If the curriculum that Eakins promoted challenged norms of Victorian propriety, it also reflected emerging aspects of modern life. For Eakins, the body was at once a work of art, a scientific subject, and a feat of engineering. Modern technology was further engaged by Eakins while at the academy in his pioneering use of photography to represent and study the body.

New Building, Modern Design

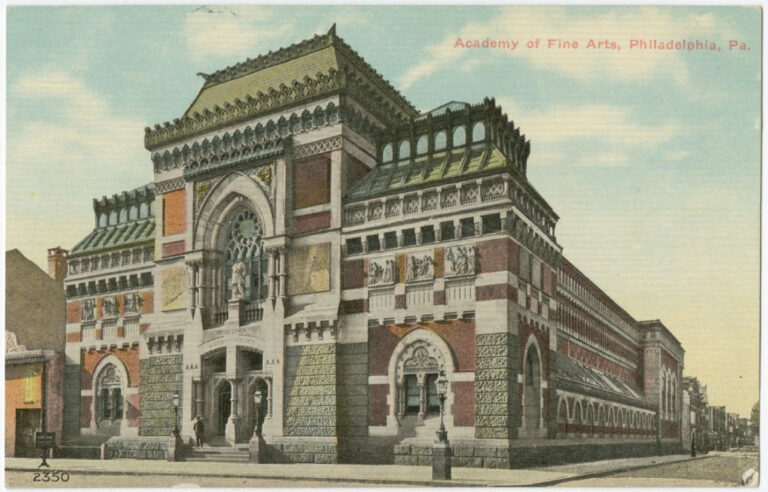

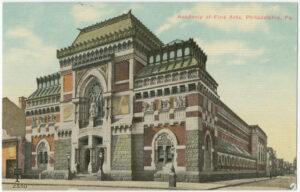

Feats of modern technology and engineering were equally pivotal to the academy’s new building that opened in 1876 on Broad Street, which was fast developing into a cultural and commercial corridor in anticipation of the City Hall soon to be constructed on Penn (Center) Square. The academy’s original buildings on Chestnut Street from 1805 and 1845 were neoclassical temples that referenced the monumental architecture of the Greeks and Romans. The new building, designed by Frank Furness (1839-1912) and George Hewitt (1841-1916), looked forward not back. Supported by academy board members Fairman Rogers (1833-1900), an engineer, and Matthew Baird (1817-77), owner of Baldwin Locomotive Works, the Furness-Hewitt design used new structural techniques and modern materials in an architectural statement that reflected the city’s industrial innovations. Its eclectic styles included Gothic, Greek, Middle Eastern, and other influences, but its most dramatic expression of modernity was the Cherry Street facade where an exposed steel truss bisected brick patterns. In the facade as well as in the building—which positioned galleries on the second floor and lecture rooms and studios on the first floor, each with appropriate natural light sources—form followed function.

In contrast to the modern building, in the late nineteenth century, the museum continued to collect American art by traditional, canonical white male artists like the Peales, although by no means was it dedicated to those artists exclusively. Indeed, as a school it continued to educate and collect the work of women like Haldeman, Cassatt, and Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942), who studied at the academy and then returned to teach in 1895 as the first full-time female faculty member.

African Americans also had a presence at the academy throughout its history. In 1834, Robert Douglass Jr. (1809-87) became the first African American artist to exhibit in an annual exhibition. Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937) studied with Eakins from 1879 to 1885, and several more African American men and women—including architect Julian Abele (1881-1950) and others who were influenced by or were part of the Harlem Renaissance—followed. The academy was by no means a sanctuary from racism, but its function as a museum and a school—with scholarships funded by the city—sometimes enabled unique access to the mainstream art world for those who were otherwise excluded.

American Impressionism Flourishes

Turn-of-the-century American Impressionism flourished at the Academy with Beaux, William Merritt Chase (1849-1916), and Thomas Anshutz (1851-1912) on the faculty and eventually in the collections. The style’s concern with technique and the very nature of painting coincided with the Academy’s longstanding academic approach to art, but its subject matter—dominated by natural landscapes—contradicted the machine age industrialism of Eakins’ concept of engineered bodies and the 1876 building. Artists of the Ashcan School, which focused on the coarser facets of modern life and the urban underclass, also trained at the academy in this time period, but the subject matter that characterized their later success departed from the middle-class subjects and serene scenery they learned to paint in Philadelphia.

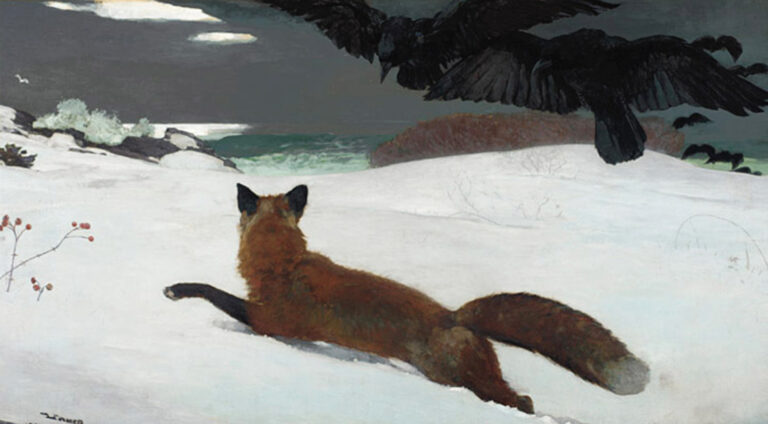

Annual exhibitions continued, and while they sometimes showcased innovative works that the academy sometimes collected, overall the institution’s direction reflected the tastes of a conservative board that continued acquiring and donating American art from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. However as managing director from 1893 to 1905, Harrison S. Morris (1856-1948) made groundbreaking acquisitions like Fox Hunt by Winslow Homer (1836-1910), Nicodemus by Henry Ossawa Tanner, and Cat Boats: Newport by Childe Hassam (1859-1935). At the same time, modernists like Charles Demuth (1883-1935) and abstract painters like Stuart Davis (1892-1964) emerged from academy classrooms in the first years of the twentieth century. As curator Sylvia Yount (b. 1955) noted: “Sometimes, in spite of itself, the academy has cultivated the more progressive impulses of its student body.”

In the following decades, the academy’s profile declined, in part because of its dedication to a traditional academic curriculum and traditional collections. In contrast, loan shows in the 1920s displayed avant-garde work, but the 1923 exhibition of the collection of Albert Barnes (1872-1951) was ill-received. The academy added a joint Bachelor of Fine Arts degree with the University of Pennsylvania in 1929 and a program in illustration in the 1930s, but art schools based wholly at universities dominated the field.

A New Institutional Self-Awareness

In the 1950s and especially in the 1970s, the academy began to explore its own history in new ways. While the 1973 exhibit “The Pennsylvania Academy and Its Women, 1850-1920” and the building’s 1976 restoration reflected a new institutional self-awareness, other groups challenged the academy for its continued traditionalism. After World War II and into the 1970s, the numbers of African American students grew. Louis Sloan (1932-2008) and Barkley Hendricks (1945-2017) both attended, then returned as faculty, and eventually earned retrospective exhibits. However, in 1971 black students and white faculty members publicly critiqued the whiteness of the academy. At graduation, the students protested, unapologetically denouncing the racism of this institution that demanded conformity to white norms of academic artistic tradition. Civil rights legislation, affirmative action, and financial aid from the city benefited African American artists at the academy, but still they struggled against the strictures of a conservative institution and a racist art world.

In 1969, the annual exhibitions ended. Over the years, the annuals, which mixed new and established artists, were a source of some of the academy’s most striking and innovative acquisitions including Fox Hunt, Nicodemus, and John Brown Going to His Hanging by Horace Pippin (1888-1946), which was shown in 1942 and purchased in 1943. Operating costs, among other factors, ended the annuals, but a shift in 1968 to an invitation-only selection process also signaled a departure from the inclusively artist-driven approach to the exhibitions that dated back to the institution’s earliest days. Into the late twentieth century, the academy was still showcasing student work in Annual Student Exhibitions, and it was also hailing former students by offering more and larger exhibits of alumni who had gone on to further success, but the openness of the annuals was missing. The academy also trended into individual blockbuster exhibits such as “To Be Modern: American Encounters with Cézanne and Company” in 1995 and “American Sublime” in 2002 that brought dramatic but temporary increases in attendance through very familiar artists.

The academy grew by adding a Master of Fine Arts degree in 1992, by purchasing the adjacent Hamilton Building in the early 2000s, and later by creating Lenfest Plaza on Cherry Street between the two buildings and installing public art there by Claes Oldenberg (b. 1929) and others. At the same time, its collecting became not only more active, but also newly proactive. In the twenty-first century, among others, it acquired the Sorgenti Collection of Contemporary African-American Art, the Linda Lee Alter Collection of Art by Women, the estate of black sculptor John Rhoden (1918-2001) for which it hired a black female curator, and the collection of African American art assembled by former superintendent of the Philadelphia School District Constance Clayton (b. 1933), much of which was created by black Academy artists. However, just as in the past, the Academy failed to realize these commitments in some ways even as it reoriented itself in others. In 2020, the administration warned students and faculty not to affiliate themselves with the school if they chose to make public statements about the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of the protest over George Floyd’s death. In response, more than a dozen students chose not to show their work in the annual exhibition.

While the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts was sometimes slow in adopting new trends in art education or in contemporary art collecting, its two-hundred-year life as both a museum and a school gave it a distinct history. Although the academy did not historically take an activist stance in relation to the racism and sexism of the art world or society at large, its students and faculty built a legacy of inclusivity. A tension between educating new generations of artists and displaying older ones as models of good taste remained, but galleries that juxtaposed work by leading contemporary African American artists with canonized white men signaled that the academy was a forward-thinking institution invested in the past, but also, at least sometimes, invested in challenges to it.

Mabel Rosenheck is a writer, lecturer, and historian in Philadelphia. She received her Ph.D. in Media and Cultural Studies from Northwestern University and now works at the Wagner Free Institute of Science and elsewhere. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- History of PAFA (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts)

- When Philadelphia's Earth Mother Bit the Dust (PhillyHistory Blog)

- After All These Years: Political, Erotical and Mystical Claes Oldenburg (PhillyHistory Blog)

- PAFA’s Historic Landmark Building: America’s first modern building (Curbed Philadelphia)