Pollution

By Stephen Nepa | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

In its various forms, pollution immeasurably shaped the history and geography of Greater Philadelphia. For nearly four centuries, contamination of the region’s air, land, and water reflected the civic and economic ambitions of people, businesses, and communities. Yet such contamination also compelled individuals, groups, and elected officials to address environmental and public health concerns while at times laying bare cases of discrimination and injustice.

Although Native Americans farmed, hunted, and erected structures in the Delaware Valley prior to European colonization, their methods generated little pollution in the modern sense. With the establishment of Philadelphia in 1682, founder William Penn (1644-1718) hoped to avoid the filthy conditions of European cities by arranging the street plan as a spacious, orderly grid. Despite his intentions, in the early 1700s fetid alleyways developed between major streets. Residents threw garbage directly outdoors, a practice that attracted feral pigs, wild dogs, and vermin. Without paved roads, foot and carriage traffic soiled the air with dust, or, depending on the weather, mud made travel impossible. Such conditions prompted Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) to call for trash collection and street paving. Performed by servants and slaves, garbage collection began in 1757, with trash hauled downstream and dumped directly into the Delaware River. Street paving commenced in 1762. Initially using brick, it largely depended upon property owners, who after contributing funds, were reimbursed by the colonial assembly.

Early industry and commerce posed threats to the environment across the region. In Wilmington, Delaware, waste from textile shops, papermakers, and flour mills polluted stretches of the Brandywine River. Philadelphia’s butchers, slaughterhouses, and breweries discharged carcasses and runoff into Dock Creek, a tributary of the Delaware River that became the city’s de facto trash dump. Petitions argued for moving tanneries, which lined the creek, to the hinterlands. Backyard privies held human waste as well as household debris. Working after dark, collectors transferred the “night soil” to holding pits outside of town for use in fertilizer. But in heavy rains, privies flooded into gutters, eventually reaching Dock Creek. In 1763, the tainted creek sparked Philadelphia’s first environmental laws, imposing fines for illegal dumping and inadequate storage of refuse. Regulations also targeted unburied animal remains, littering in public spaces and squares, and obstructive signage. Hoping to minimize noise and uncleanliness, some residents in 1773 opposed extending High Street’s crowded market stalls westward. When their lawsuit failed to materialize, they vandalized a nearby lime house in protest. New Jersey banned the burning of oyster shells to create “quicklime,” a material used in mortar. Burning shells generated a thick, acrid smoke and the law, passed in 1775, was one of the region’s first air pollution measures. During the American Revolution, fines for violating Philadelphia’s pollution laws increased eightfold due to wartime inflation.

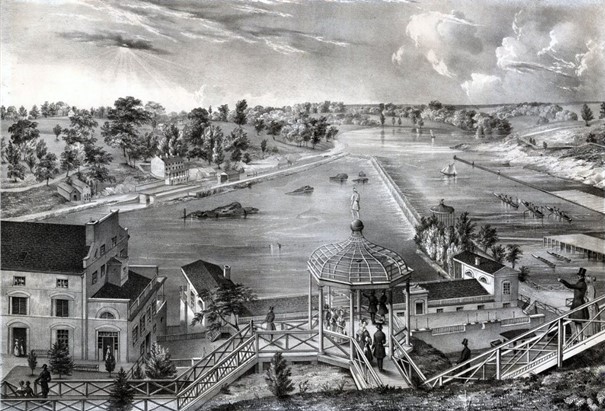

Pollution received heightened attention after independence. By 1784, Dock Creek had been covered to its mouth at the Delaware River, although underground it continued to serve as the city’s principal storm sewer. A major crisis came with Philadelphia’s 1793 yellow fever epidemic, which killed more than four thousand people. Many theories suggested the disease emanated from contaminated streets, foul privies, or in the judgment of Dr. Benjamin Rush (1746-1813), rotting cargo in the city’s port. In response, Mayor Matthew Clarkson (1733-1800) ordered the cleanup of market stalls and streets. Still others believed dirty water led to the fever’s spread. Prior to his death, Franklin bequeathed to Philadelphia funds for constructing a municipal water system. Designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764-1820), the first waterworks commenced operation in 1801. Using steam technology, the system delivered clean water to homes and businesses, reducing the need for private wells. Despite these innovations, leading intellectuals such as Rush and Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) openly questioned the need for and the health of urban environments. And since colonial times, the region’s affluent classes tended to own country houses, providing respite from increasingly toxic cities and their civic obligations to address such toxicity.

Toll of Expanding Industries

With expanding industries and transportation networks in the 1800s came new forms of pollution. To blunt the effects of water contamination, Philadelphia in the 1820s began acquiring private estates along the Schuylkill River for the establishment of Fairmount Park; in subsequent decades, the park’s boundaries grew to maintain a buffer between the growing industrial city and its wooded hinterlands. Effluent from coal-heaving in Manayunk, gunpowder making in Wilmington, and iron founding in Philadelphia entered creeks and rivers. Ferry passengers and operators routinely threw their waste overboard. Trains, running at street level, contended with pedestrian and equestrian traffic, which led to extreme congestion. Locomotives emitted noxious black smoke and were prone to explosion. In 1838, Philadelphia banned them from all streets, necessitating the construction of train stations beyond city limits. Meanwhile thousands of work horses augmented travel and transport. On average, each animal generated twenty pounds of manure and several gallons of urine per day, and cities found it difficult to secure the resources needed to keep pace with cleanup. Adding to water pollution were the refineries built along the Schuylkill River adjacent to Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park after the discovery of oil in 1859 at Titusville, Pennsylvania. The first, the Belmont Petroleum refinery, opened in 1865 just upriver from the Fairmount Waterworks. The refinery contained underground storage tanks and a waste pipe running directly into the river. In 1870, to curb toxic runoff, the city purchased Belmont’s land, prompting its relocation downriver to Point Breeze; the parcel later was merged into Fairmount Park. In addition, a new law required all refining activities be positioned south of the waterworks to prevent future contamination.

Following the Civil War, with rapid population growth and industrialization, contaminated water ranked among the region’s most serious problems. By 1880, nearly thirty thousand tons of privy waste was collected annually in Philadelphia. Although flush toilets had come into use, early models were connected to privies, which overwhelmed municipal systems. Raw sewage, along with coal ash (from homes and businesses), industrial runoff, and household items was deposited directly into the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers. Wilmington’s Brandywine River, the city’s main water source, also was heavily polluted. Outbreaks of cholera and typhoid fever occurred in the 1880s, prompting the building of reservoirs, a modern sewer system in 1890, and in 1909, Wilmington’s first water purification plant. Philadelphia’s City Council in 1900 approved funding for a municipal filtration system, which nearly eradicated typhoid.

Disease epidemics were especially worrisome in crowded neighborhoods populated by European immigrants and migrating African Americans. Seeking to improve public health and combat poverty, charitable Philadelphians such as Theodore Starr (1841-84), Susan Parrish Wharton (1852-1928), Hannah Fox (1858-1933), and Helen Parrish (1859-1942) helped form the Octavia Hill Association, which, influenced by British settlement programs, spearheaded housing reform in south Philadelphia. Fearing a cholera outbreak in the same vicinity, the city launched an asphalt paving campaign in 1893. With workhorses plying the streets, sanitary officials, concerned with maladies spread by manure dust, lobbied for asphalt citywide; compared with block paving, asphalt cost less and proved easier to clean. Personal hygiene and pollution became intertwined when in 1897, Philadelphia’s Women’s Protective Health Association posted signs throughout the city warning of the dangers of public spitting, which many believed transmitted disease. In 1905, Dr. Lawrence Flick (1856-1938), a Jefferson Medical College graduate who made strides curing tuberculosis, further condemned the practice in On Spitting, a pamphlet he distributed to grocery stores, taverns, and passersby.

Persistent Water Contamination

Despite earlier efforts to combat it, water pollution continued to pose significant problems near the turn of the twentieth century. Philadelphia’s North American in 1899 bemoaned the contamination of Frankford’s Little Tacony Creek and called for its conversion into a sewer line, a process not completed until the 1930s. Although some municipalities had banned releasing sewage into waterways, many continued to do so. Human waste was blamed for typhoid outbreaks in Trenton, New Jersey, and for high mortality rates among the poor, whose dwellings lacked flush toilets or indoor plumbing; in 1913 alone, eighteen hundred Philadelphia children succumbed to gastrointestinal ailments, with many linked to sewage-contaminated water. The following year, fears of bubonic plague launched the Philadelphia’s Bureau of Health “kill the rats” campaign. The city offered advice on trapping and pledged five cents for those captured alive and two cents for those dead. “Rat patrol” agents walked the docks, setting traps and a receiving station, erected on the Race Street Pier, took in more than five thousand specimens by January 1915. Concerns also mounted over worsening air quality due to coal burning, factory emissions, and the hundreds of trains operating in the region. In 1902, the Philadelphia Inquirer lamented the city’s “intolerable smoke nuisance,” comparing its sooty atmosphere to that of London. Across the river, Camden’s City Council in 1910 heard petitions against the Pennsylvania Railroad, whom citizens accused of “befogging” downtown with locomotive smoke. Automobile emissions in the early twentieth century added to the region’s already bad air, prompting Philadelphia journalist Christopher Morley (1890-1957) to describe in 1919 a “haze that is part atmospheric and part gasoline vapor.”

As the middle of the twentieth century approached, the Delaware River’s sections at Philadelphia were some of the country’s most contaminated. From the city south to Marcus Hook, Pennsylvania, the river effectively was a dead zone. Fish kills were common, and in summer months bacteria caused oxygen levels in the river to plummet. Pilots received warnings about the river’s odors as they flew overhead while some ship captains, due to the smell, refused to dock. Chemical production in Wilmington and Newport, Delaware, led portions of the Brandywine and Christina Rivers to suffer similar fates. Although Philadelphia began upgrading its sewage treatment system in 1947, manufacturing waste continued to flow freely into rivers and creeks. By 1950, Philadelphia contained two-thirds of the region’s industry, the majority in chemicals, metals, paper products, petroleum refining, and plastics. The remaining share was spread among smaller industrial cities along the Delaware River: Wilmington, Delaware; Chester, Pennsylvania; and Camden and Trenton, New Jersey. At the time, no legislation required factories to limit waterborne pollutants and without air monitors in use, atmospheric contamination also faced little scrutiny. During his mayoral tenure, Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974) targeted Philadelphia’s open trash dumps, eventually forcing them to close in 1957. Incinerators then handled solid waste, emitting hazardous fly ash particles. The area’s largest, on the Delaware River at Philadelphia’s Spring Garden Street, by 1960 processed six hundred tons of garbage per day. In 1961, Pennsylvania Governor David L. Lawrence (1889-1966), who as mayor of Pittsburgh had combated his city’s notorious air pollution, convinced President John F. Kennedy (1917-63) to create the Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC), the country’s first federal river compact to address pollution. Yet funding and action proved difficult. One million pounds of waste entered the river every day in 1964, with 60 percent coming from sewage treatment plants.

Concerns over pollution reached a national crescendo in the 1970s, as many Americans embraced environmentalism and the federal government enacted laws for resource and wilderness protection. At the local level, the health of the Delaware River and solid waste disposal remained intractable problems. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) declared the river “unfishable” in 1973, citing the disappearance of once-plentiful shad and striped bass populations.

Clean Water Act of 1972

Although sewage treatment plants had yet to meet standards mandated by the DRBC, the Clean Water Act of 1972 imposed federal restrictions on wastewater and pollutants. In addition, the region’s widespread loss of factory jobs, while leaving behind contaminated properties, over time minimized industrial discharge into the river. By the early 1980s, local fishermen reported improved conditions and greater visibility. Although Philadelphia’s trash incinerators complied with federal emissions standards, lawsuits, beginning in 1971 and accusing the city of air polluting, forced their closure. Until the mid-1980s, New Jersey stood as the primary recipient of Philadelphia’s trash. By then, a number of regional landfills, such as Lipari in Pitman, New Jersey, and Tybout’s Corner in Wilmington had been shuttered and declared Superfund sites. The struggle to rid itself of garbage earned the city the unflattering nickname “Filth-adelphia,” a source of national embarrassment.

By the 1990s, the environmental justice movement bore significant fruit in greater Philadelphia. Whether addressing mesothelioma among former asbestos workers in Ambler, Pennsylvania; residential proximity to oil refineries in southwest Philadelphia and railyards in Camden; or excessive jet engine noise in Tinicum, Pennsylvania, several communities challenged the parallels between racial and class discrimination and pollution. This became especially evident in Chester, which in 1996 the New York Times labeled “the waste-processing capital of Pennsylvania.” Already polluted by decades of steelmaking, shipbuilding, and heavy manufacturing, the impoverished, black-majority city’s waste plants handled all of Chester County’s trash and 85 percent of its sewage. While surrounded by affluent suburban towns, the EPA declared the city had the state’s highest infant mortality rate while the Center for Disease Control (CDC) found excessive lead levels in more than half of the city’s children. Lead poisoning, from tainted water, soil, or household paints, also threatened low-income families in North Philadelphia, Bridesburg, and Kensington. In Camden, New Jersey’s most impoverished large city, officials beginning in the 2010s spent nearly $5 million annually to remediate illegal dumping sites while groups such as South Camden Citizens in Action brought lawsuits against smelting, cement grinding, and gasoline station operations that threatened the environmental health of the Central Waterfront neighborhood. The city’s Covanta Energy Recovery Center, a massive incineration plant adjacent to Newtown Creek, discharged more than 350 pounds of lead into the air each year; as of 2019, the center processed more than one thousand pounds of solid refuse each day.

Greater Philadelphia confronted myriad sources of pollution in the early twenty-first century. Many cities contained Superfund sites in various stages of remediation and brownfields in need of development, with notable successes at Wilmington’s Justison Landing, Trenton’s Waterfront Park, and Philadelphia’s Reading Viaduct Rail Park. Yet the region continued to witness dangerous cases of pollution. In 2012, a Conrail freight train derailment in Paulsboro, New Jersey, caused thousands of pounds of vinyl chloride to spill into the air, leading to eye and lung ailments among residents. Five years later, the notorious “El Campamento,” an illegal squatter camp populated by victims of Philadelphia’s opioid crisis, was forcibly cleared from a Conrail-owned underpass in Kensington. Nearby residents had long complained of human waste, discarded syringes, and debris littering the area. That same year, greater Philadelphia ranked as the second-worst Northeastern metropolitan area (behind Washington, D.C.) for smog contamination. And in June 2019, a massive explosion and fire at the Philadelphia Energy Solution (PES) Oil Refinery terrified nearby residents with worry over airborne pollutants.

As one of the largest metropolitan areas in the country, greater Philadelphia continued to cope with pollution and its many sources. Although attempts to monitor and limit contamination began during the colonial period and intensified with subsequent generations, the region continually confronted threats to the air, land, and water.

Stephen Nepa teaches history at Temple University, Pennsylvania State University-Abington, Rowan University, and Moore College of Art and Design. He is a contributing author to numerous books and journals, and regularly appears in the Emmy Award-winning documentary series Philadelphia: The Great Experiment. His current research explores food and drink at the 1876 Centennial Exposition. He received his M.A. from the University of Nevada and his Ph.D. from Temple University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Why racial disparities in asthma are an urban planning issue (WHYY, May 21, 2019)

- Philly hits a ‘crossroads’ of environmental justice at ex-PES oil refinery (WHYY, January 14, 2022)

- The death of the Delaware River (WHYY, January 15, 2019)

- Exhibition traces a 200-year history of water pollution in Philadelphia (WHYY, September 11, 2021)

- Unexpected upside to coronavirus shutdown? Cleaner air. (WHYY, March 18, 2020)

- Timeline: The Delaware River and the Clean Water Act (WHYY, January 15, 2019)

- EPA takes up environmental justice complaint against Philly’s permit for SEPTA power plant in Nicetown (WHYY, July 19, 2021)

Links

- Back When We Burned Trash On The Delaware River (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- A Crude Awakening: Explosion On The Schuylkill Brings Philly’s History Of Oil Refineries Into Focus (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The Delaware River Revival (UD Water Resources Center)

- Be Thankful You Don't Live in Pre-Flush Philly (Philadelphia Water Department)

- The Watering of Philadelphia (Pennsylvania Heritage)