Postal Services

Essay

Philadelphia played a significant role in establishing and innovating postal services in the British colonies in North America and across the expanding United States. In Philadelphia, actions by the Second Continental Congress, the Constitutional Convention, and the U.S. Congress made mail delivery a function of American government. Important innovations occurred during the postmasterships of Philadelphians Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) and John Wanamaker (1838-1932). As delivery of mail extended across the continent with riders on horseback and drivers of stagecoaches, and later by steamboats, railroads, airplanes, and motor vehicles, the Philadelphia region’s reach extended across an increasingly complex and far-flung network of communication.

The region’s earliest known mail carriers were indigenous Lenape runners, whom Dutch colonizers hired in the mid-seventeenth century to carry letters between settlements on the lower Delaware River (later Delaware) and the island of Manhattan. Lenape mail-runners became fewer as English colonizers displaced the Dutch and set up post offices, where private couriers could pick up and deliver mail. William Penn (1644-1718) established a post office in Philadelphia in 1683 to facilitate mail between the Falls of Delaware (Trenton, New Jersey) and Maryland. After 1691, when the Crown established a private monopoly post office to serve all English colonies in America, absentee owner Thomas Neale (1641-99) appointed New Jersey Governor Andrew Hamilton (?-1703) to head the enterprise. Post offices established in Burlington (1693) and Perth Amboy (1692), New Jersey, enabled mail between Philadelphia and New York, and weekly deliveries served major towns in the middle colonies and New England.

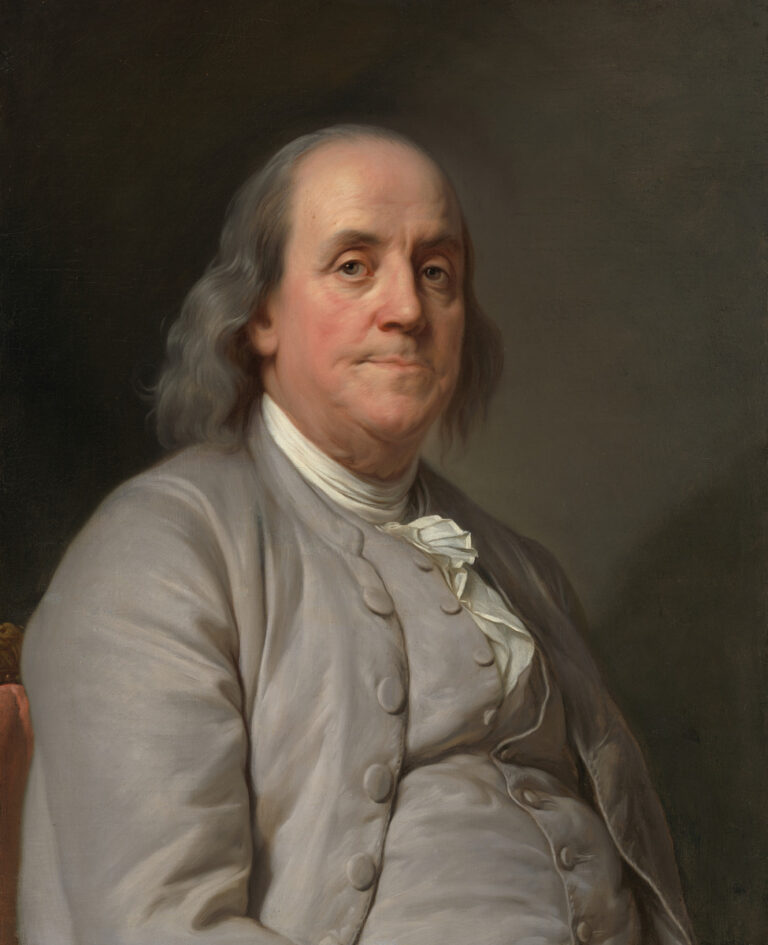

Benjamin Franklin entered postal service history in 1737, after control of postal services reverted to the British government. Appointed local postmaster for Philadelphia, Franklin ran the post office with his wife, Deborah (1707-74), from his successful print shop on High (Market) Street near Second Street. Newspaper publishers like Franklin often served as postmasters, which gave them advantages for circulating their publications and gaining access to news. But Franklin’s interest in the mail also aligned with his other expanding intercolonial activities, such as scientific exchanges among members of the American Philosophical Society (which he founded in 1743). In 1753, Franklin successfully lobbied to be appointed postmaster general for the colonies, a position he held jointly with his friend and fellow printer William Hunter (?-1761), the postmaster of Williamsburg, Virginia.

Innovations to Speed the Mail

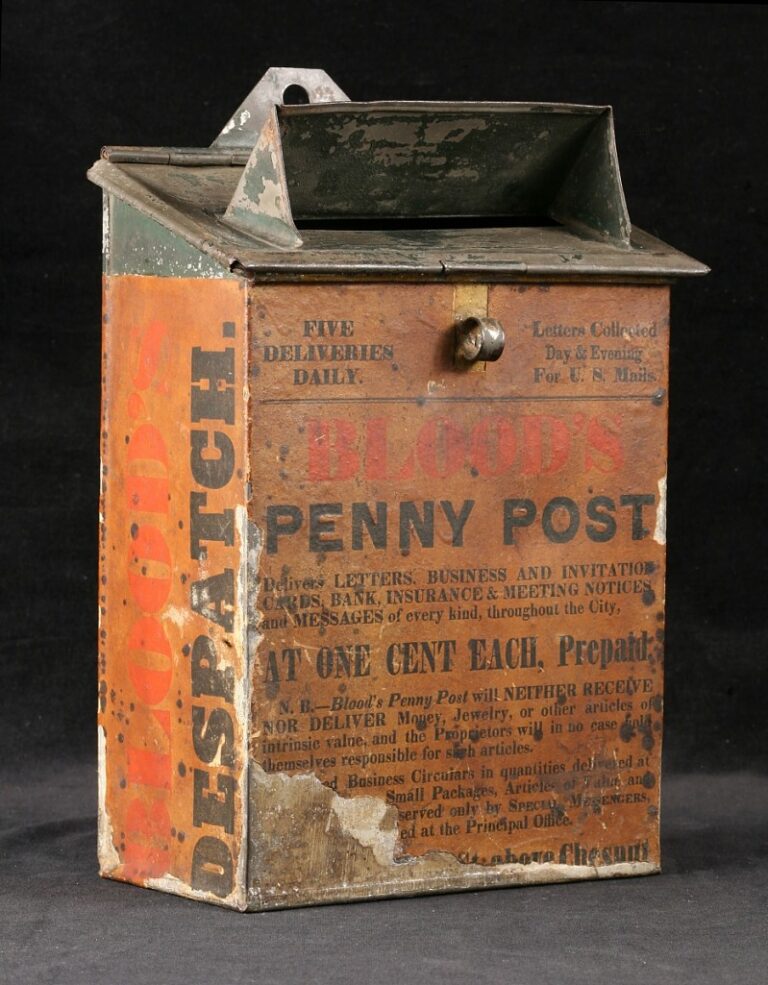

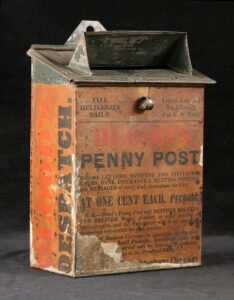

Franklin retained his royal appointment until his sympathies with the rebellion brewing in the British North American colonies led to his dismissal in 1774. Although he spent long periods of time in England, where he served as agent for Pennsylvania and other British colonies, Franklin has been credited with introducing innovations that enabled faster, more reliable communication along the Atlantic seaboard. The number of post offices between Philadelphia and New York expanded to seven, and the speed of delivery between the two port cities increased with the addition of nighttime post riders. Franklin inspected post offices throughout the northern colonies and surveyed new routes to reorganize the system. American post roads (the routes for carrying mail) extended south to Florida and north to Maine and parts of Canada. Franklin also instituted new accounting methods, and for the first time the American postal service turned a profit. The innovation of the “penny post” allowed recipients to pay for their mail to be home-delivered from the post office.

Franklin’s reputation led to his appointment by the Second Continental Congress as the first postmaster of the new United States. By November 1776, however, he turned the work over to his son-in-law, Richard Bache (1737-1811), who served until 1782. Mail delivery remained a power of government under the Articles of Confederation and in Article I of the U.S. Constitution, heeding arguments by Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush (1746-1813) and others that a postal system would serve the vital purpose of uniting a growing, informed citizenry. As the new nation came to fruition, new post roads connected Philadelphia westward as far as Pittsburgh. While Philadelphia served as the nation’s capital during the 1790s, Congress passed the Postal Act of 1792, which set special low rates for mailing newspapers, a boost for the circulation of local papers covering the federal government but also a benefit for countryside editors who reprinted news from exchange papers they received. The 1792 law also prohibited public officials from conducting surveillance of mail and gave Congress authority to designate postal routes, an important power for shaping the nation’s further expansion.

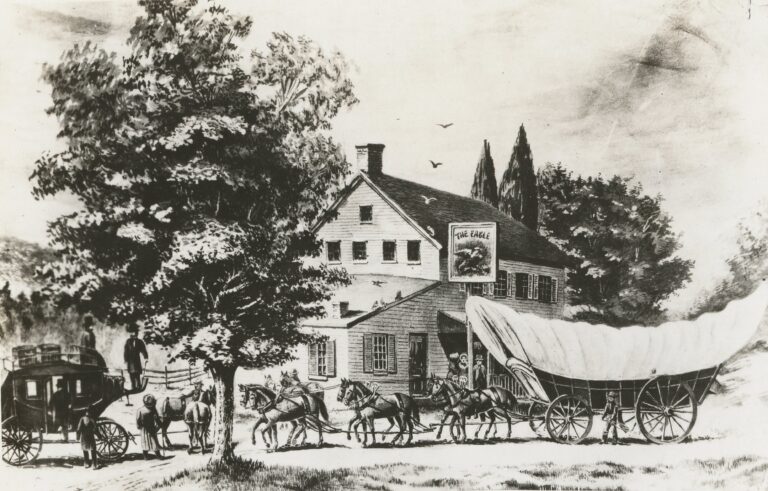

Administration of the postal service moved to Washington, D.C., with the rest of the federal government in 1800, but Philadelphia and the surrounding region continued to benefit from expansion of the system. Innovations in transportation added to the reach and speed of mail. The government contracted with stagecoaches to carry mail as early as 1785, and stagecoach “express routes” continued into the early nineteenth century. Stagecoach operator James Reeside (1789?-1842), based in Philadelphia starting in 1820, instituted a line of speedy, flashy red coaches between Philadelphia and New York and then expanded to Pittsburgh and beyond to become the largest mail contractor in the country. Steamboats also moved mail to the South and West, and a greater leap of speed came with railroads beginning in the 1830s. Early contracts for railroad transportation of mail included a route between Philadelphia and West Chester in 1832 and between Philadelphia and Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania, in 1836; in New Jersey, the Camden and Amboy Railroad began to carry mail in 1834. Over the next four decades, postal service spanned the continent by overland stagecoaches and pony express riders, and finally with completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869.

Wanamaker Introduces Commemorative Stamps

Nationwide postal service required a vast federal bureaucracy, which created equally vast opportunities for political patronage. Philadelphia’s next noteworthy postmaster general, department store innovator John Wanamaker, gained the position in 1889 as a reward for fund-raising for President Benjamin Harrison (1833-1901). Wanamaker brought his flair for modern marketing to the task, for example introducing commemorative stamps, which became wildly popular. He also proposed parcel post and rural free delivery, although these services did not come to fruition until after his term. Wanamaker’s religious convictions shaped some of his actions, for example ending deliveries on Sundays and banning lottery tickets from the mail.

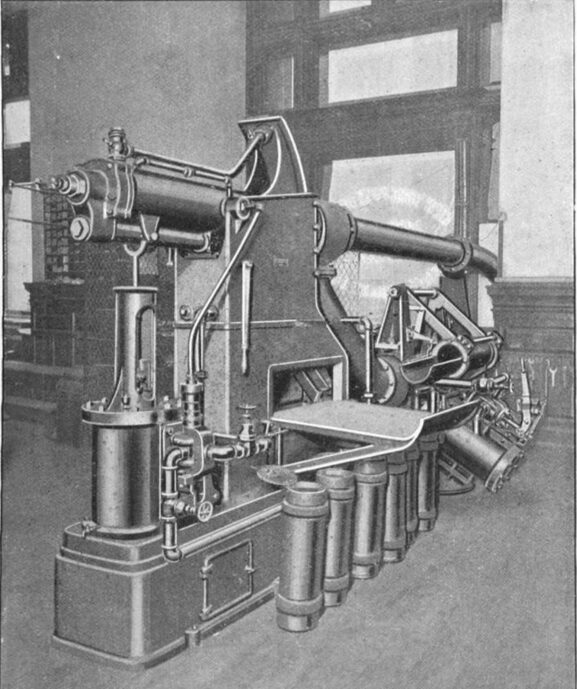

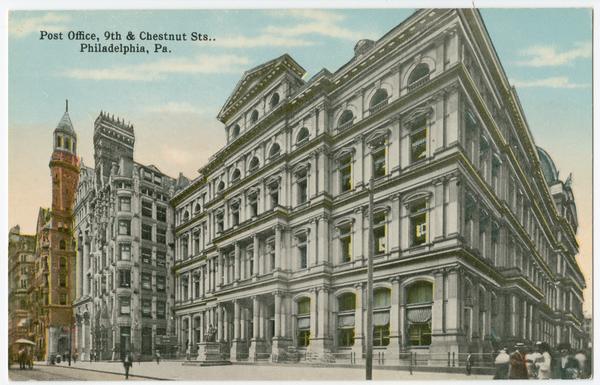

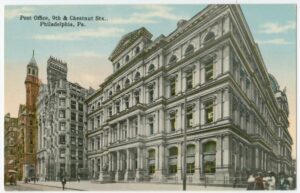

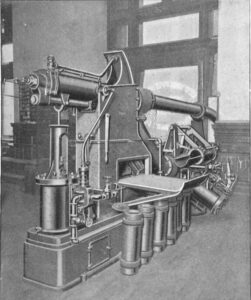

As in his department stores, Wanamaker sought to deploy modern technologies. With Philadelphia as one of the trial cities, Wanamaker introduced pneumatic tubes to speed mail between urban post office locations. The system involved six-inch pipes buried underground, with canisters full of mail hurtling through the pipes at high speed by force of air pressure. Wanamaker inaugurated Philadelphia’s first tube in 1893 by sending a Bible wrapped in an American flag from a substation near Fourth and Chestnut Streets to the main post office then located at Ninth and Chestnut. The delivery took sixty-two seconds. Philadelphia’s tube system subsequently expanded to more than nineteen miles connecting the main post office with business locations like the Bourse, other substations, and the city’s primary railroad stations. Congress perennially questioned post office expenditures on the tube systems, however, and government-funded tubes ceased operation in Philadelphia and elsewhere in 1918.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, postal delivery innovations turned to the air, with Philadelphia playing a literally pivotal role due to its location between Washington, D.C., and New York City. Federal postal authorities chose a site in Bustleton, Northeast Philadelphia, for an airfield where planes carrying mail simultaneously from New York and Washington would land and hand off their mail bags to fresh planes and pilots for the rest of the route. Experienced Army pilots carried out the experimental service between May and August 1918, often successfully but occasionally getting lost in fog or emergency-landing in Maryland or New Jersey farmland. The Post Office Department then took over the service and by 1919 extended airmail delivery across the continent, initially with a series of short connecting flights reaching from New York to San Francisco (stopping not in Philadelphia, but in central Pennsylvania in Bellefonte, Centre County). Transatlantic airmail began in 1939, but again originating from New York.

Largely out of the national spotlight for the rest of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the Philadelphia region’s mail delivery benefited and suffered from continuing changes in technology and management of the nation’s vast postal network. Capacity and speed increased with automated sorting and zip codes (introduced in 1963), and trucks and airplanes moved more of the mail as railroads declined. Motorized routes served the expanding suburbs. But mounting debts and inefficiencies plagued the system, leading to the Postal Reorganization Act of 1970, which ended the federal Post Office Department and transferred its functions to the United States Postal Service, a government-owned corporation. By the early twenty-first century, the system continued to struggle as electronic communication drastically cut the volume of physical mail and private carriers like UPS competed effectively to deliver packages. Cost-cutting measures led to closures of many local post offices in communities across the region. Mail-sorting operations in Philadelphia moved in 2006 from the main post office at Thirtieth and Market Streets (opened in 1935) to a new facility near Philadelphia International Airport, shedding about six hundred jobs in the process.

Regardless of continuing changes in technology and mail habits, Philadelphia maintained at least one distinctive place in the nation’s mail service: the place where stamps are affixed to the corners of envelopes. Symbols of Philadelphia appeared on postage stamps beginning with the first American stamps issued in 1847, which depicted Benjamin Franklin as well as George Washington. Over the years, Americans attached numerous stamp-sized renderings of the Declaration of Independence, Independence Hall, and even the LOVE statue to their mail. In 2007, when the Postal Service issued the first “forever” stamp without a printed postage rate, the stamp bore a picture of the Liberty Bell. Chosen for its apparent timelessness as a national symbol, the iconic bell also connected the latest postal service innovation with Philadelphia and its longstanding role in mail delivery in the United States.

Charlene Mires is Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden and editor-in-chief of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2024, Rutgers University.