Sesquicentennial International Exposition (1926)

Essay

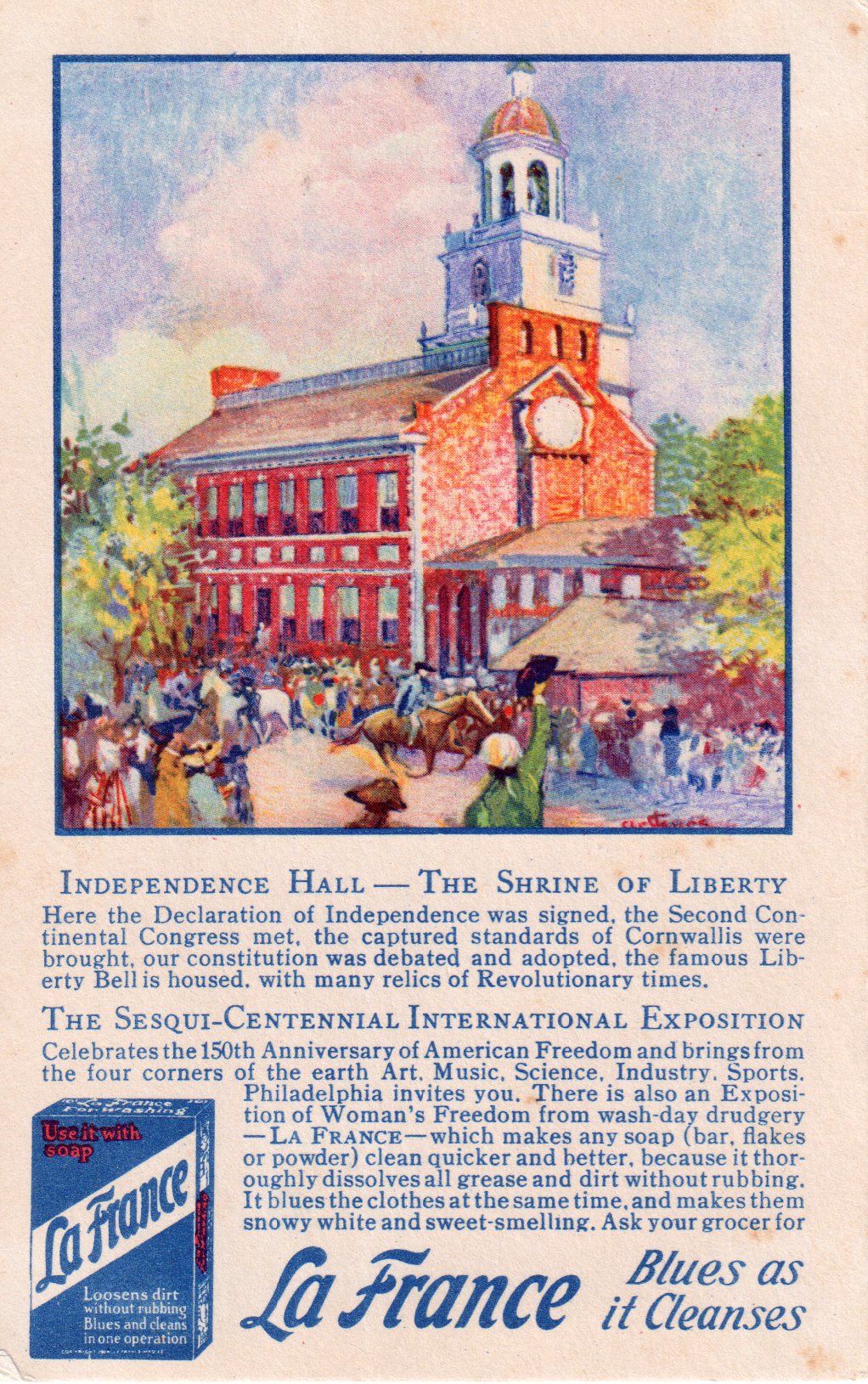

In 1926, Philadelphia hosted the Sesquicentennial International Exposition, a world’s fair, to commemorate the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Although it opened to great fanfare, the exposition failed to attract enough visitors to cover its costs. The fair organization went into receivership in 1927 and its assets were sold at auction.

The idea to commemorate the signing of the Declaration of Independence by holding a world’s fair originated in 1916 with John Wanamaker (1838-1922), owner of Wanamaker’s department stores and lone survivor of the 1876 Centennial Exposition’s Finance Committee, who called upon Philadelphia to host an industrial and commercial exposition that would fittingly mark the birth of the United States. World War I temporarily derailed planning, but in 1920, Mayor J. Hampton Moore (1864-1950) and a group of leading citizens took up the effort; they incorporated the Sesquicentennial Exhibition Association (SCEA) in 1921.

Planning for the fair suffered, however, from struggles for control of the SCEA and from SCEA members’ divergent visions of what the exposition should emphasize. Should it celebrate commerce or should it stress progress in the arts, science, and education? Mayor Moore and the Chamber of Commerce, headed by Alba B. Johnson (1858-1935), favored the commercial vision. For them the fair was a business opportunity, a chance to use Philadelphia’s historic legacy to attract visitors (and their dollars) to the city. Championing the opposing view was Edward W. Bok (1863-1930), editor of Ladies Home Journal and son-in-law of Cyrus H. K. Curtis (1850-1933), Philadelphia publishing magnate. An immigrant who had made good in America, Bok sought to enhance the reputation of his adopted city. He wanted to broaden the appeal of the fair both nationally and internationally by avoiding crass commercialism and by emphasizing Philadelphia’s role in American history.

Hoover Offered Directorship

Bok tried to wrest control of the SCEA from Moore in 1922 by offering to pay out of his own pocket a $50,000 annual salary for up to five years for a Director General of the fair. Bok had a specific candidate in mind: Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover (1874-1964), who had called publically for the fair’s organizers to subordinate its commercial aspects to its idealistic ones. Hoover turned down the job, however. Bok then extended the offer to Charles M. Schwab (1862-1939) of Bethlehem Steel, who also declined. The search for a Director General was put on hold, but Bok continued to push for a more high-minded affair, even suggesting the fair be renamed “The Liberty Fair for World Peace and Progress.”

Planning also was hampered by a lack of public enthusiasm. Attempts to get city residents to fund the exposition by buying shares in the SCEA were unsuccessful. Residents also actively protested the original proposed site for the fair in Fairmount Park. Worried that taxes would be increased for an enterprise that would only benefit real estate and commercial interests, they argued that Philadelphia needed housing and new infrastructure, not an international party. Church leaders warned the fair would attract criminals and other undesirables. Labor feared higher prices resulting from increased numbers of visitors to the city. Because unemployment was low, they saw no need for temporary jobs, which they believed would attract people from out of the city and add to competition for jobs after the fair. Management feared higher wages and losing workers to jobs at the fair ground.

Opposition coalesced in the Anti-Sesquicentennial League. Even Mayor Moore, who resigned as SCEA president in May 1922 in part because of his clash with Bok and in part because he realized that public support for the enterprise was thin, came out publicly against the fair by the end of 1923.

By the time W. Freeland Kendrick (1873-1953) became mayor in 1924, little planning for the fair had been accomplished. Kendrick, a member of the Republican political organization headed by William Vare (1867-1934), took charge of the SCEA. He abandoned the Fairmount Park site and relocated the fair on previously undeveloped land in Boss Vare’s backyard in South Philadelphia just above the Navy Yard at League Island. Vare and his associates cared little about the vision for the fair. Instead, they focused on the profits they would earn from city contracts and increased property values. The swampy land was drained and filled in (with dirt excavated from the North Broad Street subway project), and construction began on the exposition’s buildings in the fall of 1925.

Fair Ran From May 31 to Nov. 30

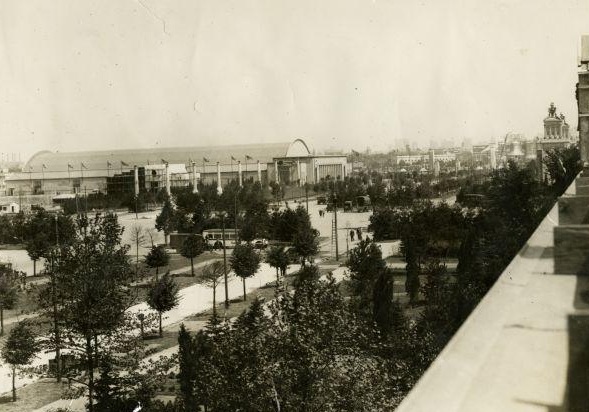

The fair opened on May 31, 1926, and ran through November 30, in South Philadelphia between the Naval Yard and Packer Avenue, and between Tenth and Twenty-Third Streets. On hand to participate in the opening ceremonies with Mayor Kendrick were Secretary of Commerce Hoover and Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg (1856-1937). Unfortunately for early fair goers, the fair was open, but it was not quite finished. Several buildings remained under construction until late July, nearly two months into a six-month run.

When construction was complete the fair offered an impressive collection of buildings. Five large “palaces,” or exhibition halls, provided acres of indoor exhibition space, and pavilions represented thirty-one states, four territories, and nine foreign nations. The city built the permanent, horse-shoe-shaped Municipal Stadium (renamed John F. Kennedy Stadium in 1964 and torn down in 1992), measuring 710 by 1020 feet, on the fair grounds. It became the site of a recurrent patriotic pageant called “Freedom,” large outdoor religious services, and various sporting events (including the championship boxing match between Gene Tunney and Jack Dempsey on September 23 attended by 125,000 people in the pouring rain). A re-creation of colonial Philadelphia’s High Street featuring more than twenty buildings was another highlight. Fair-goers also found a Forum of the Founders consisting of thirteen pylons, each thirty-nine feet high, representing the original colonies. The Sesquicentennial had a ten thousand-seat auditorium, an emergency hospital, a fire station, and its own working Post Office.

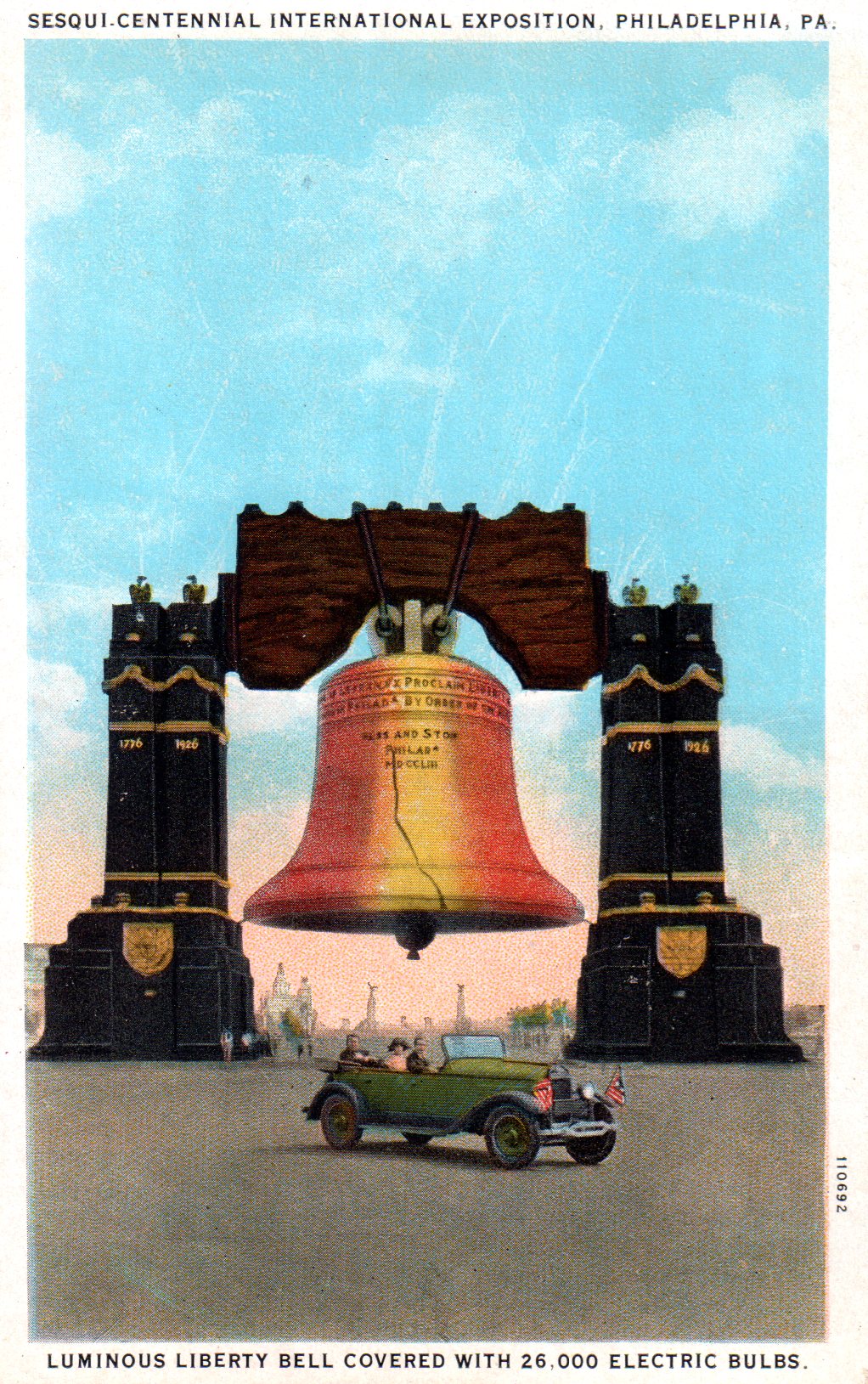

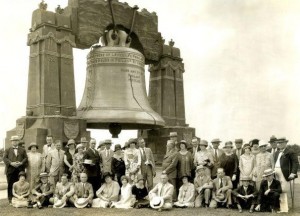

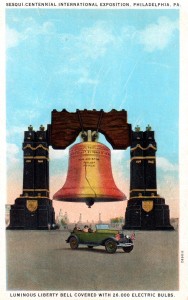

Straddling Broad Street just above the fair’s entrance on Packer Avenue was an eighty-foot-high replica of the Liberty Bell with 26,000 fifteen-watt light bulbs, part of an elaborate lighting scheme for the fair. The exhibition halls, each painted a different pastel shade, were lit at night with mechanically rotating lights. Stadium lighting allowed various sports to be played at night. On June 6, construction began on a 175-foot tall Tower of Light that was designed to cast a beam of light seventy miles. Unfortunately for visitors, fair organizers ran out of money before the tower was completed.

Disappointing Attendance

In spite of the fact that fifty million people lived in the region within 500 miles of the fairgrounds, thus prompting predictions that thirty million people would visit the exposition, only 4,622,211 people actually paid to attend (of 6.4 million total attendees). Attendance figures were so bad by the end of June that the organizers decided to violate the city’s 132-year old Blue Laws and open on Sunday. The act allowed people who worked six days a week to attend, but it angered the city’s Sabbatarians, still a force in 1926. Poor attendance prompted fair organizers to keep the grounds open for the month of December to give concessionaires a chance to sell remaining stock.

There were several reasons for the fair’s failure. The bickering among its organizers and public opposition was compounded by bad word-of-mouth advertising that stemmed from the ongoing construction when it opened, and bad weather—it rained 107 of the 184 days the fair was open. Some scholars suggest that mass availability of automobiles and motion pictures after World War I relegated all world’s fairs to obsolescence (a notion challenged by later successful fairs). Whatever the reason, after the fair closed, four hundred creditors presented bills totaling $5.8 million. It took until May 1929 for the city to pay off the Sesquicentennial’s tab.

Freed for development after the fair, the grounds of the Sesquicentennial International Exposition became Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) Park, Marconi Plaza, the Packer Park neighborhood, and the sports complex. Following the great success of the Centennial Exhibition in 1876, the Sesquicentennial of 1926 proved to be a disappointment. The city initiated planning of another fair for the Bicentennial in 1976, but it refused to host another exposition without funding from the federal government.

Martin W. Wilson is Associate Professor of History at East Stroudsburg University. This essay draws upon his research on the history of tourism in Philadelphia between 1926 and 1976. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Mapping the Sesquicentennial (PhillyHistory.org)

- A Royal Visit to the Sesquicentennial (PhillyHistory.org)

- Cowgirls and Calf Roping at the Sesquicentennial (PhillyHistory.org)

- A Classical, Paper-Mâché Gas Station at the Sesquicentennial (PhillyHistory.org)

- Pageantry at the Sesquicentennial (PhillyHistory.org)