Sports Cards

Essay

Sports card collecting, a classic American hobby, has strong ties to Philadelphia. Its history can be traced through Philadelphia firms such as the American Caramel Company, Fleer Corporation, and Bowman Gum Company. Those three, all pioneers and innovators in the sports card industry, helped to build collecting as a popular hobby.

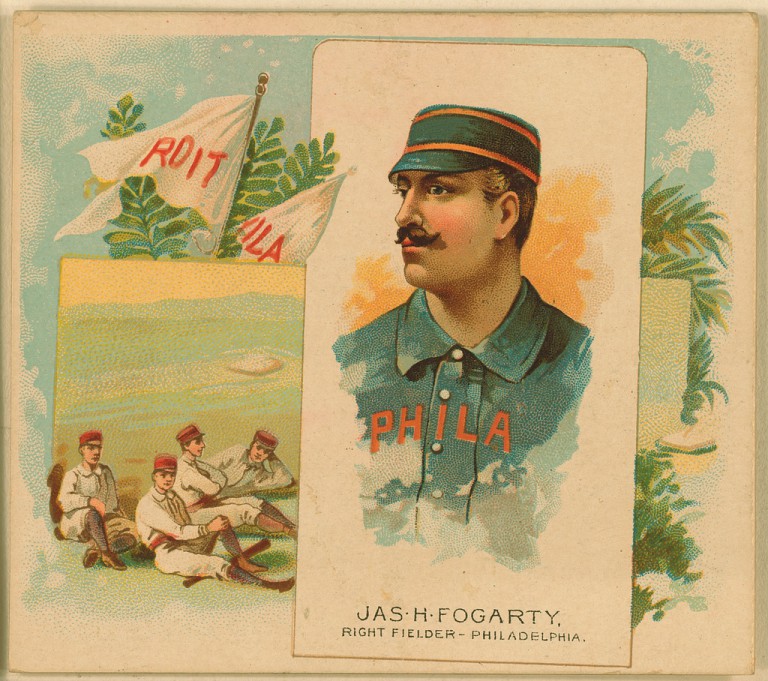

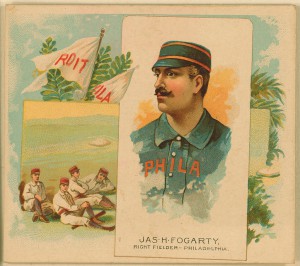

Sports cards developed from the cardboard originally used by tobacco companies as pack stiffeners to protect cigarettes from bending and breaking. Companies quickly learned that placing images on the cardboard might attract additional customers. By the late 1880s, starlets, boxers, and flags became popular features on sets of cigarette cards. Sports stars, particularly baseball players, emerged as the main subjects as they appeared increasingly across a variety of sets.

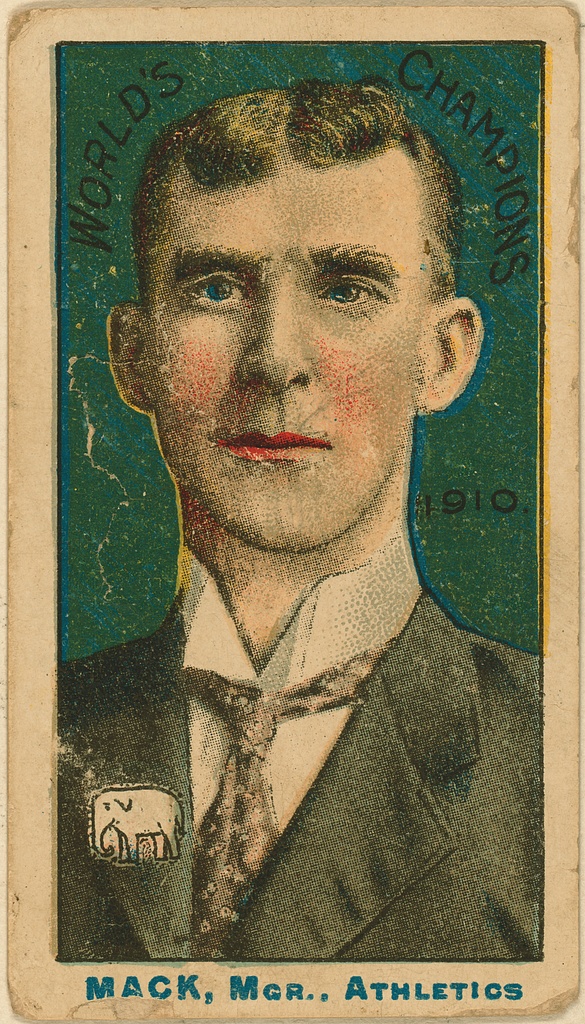

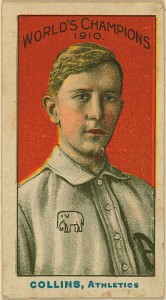

In the early twentieth century, companies in many industries began to entice customers by issuing sports cards with their products. Production of sports cards in Philadelphia began in 1908 when American Caramel Company, founded in 1898, included them as inserts in boxes of caramels. The company started by producing a small set of thirty-three local baseball players, with one card placed in each candy box, and the next year expanded to at least 106 different players from a variety of teams on at least 120 different cards. American Caramel also printed a prize fighter set of twenty boxers and in 1910 added “Teddy’s Trophies” showing thirty types of animals hunted in Africa by Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919). The company continued to produce sports cards, with interruptions during World War I and for a five-year period in the 1920s, until it closed in 1928 in the face of increasing competition among caramel makers.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Philadelphia companies pioneered the practice of packaging sports cards with chewing gum. Fleer Corporation, founded in Philadelphia in 1888 and located in Olney by the 1930s, introduced a set of 120 cards featuring baseball players and other athletes in 1923 but then stopped production. The cards were not popular enough to boost business. Although the company found greater success after one of its accountants, Walter Diemer (1904-98), invented a recipe for bubble gum (marketed as Dubble Bubble), Fleer went out of the sports card industry. Philadelphia gained another card producer in 1939, when Gum Inc., located in Germantown, produced a set of 250 cards featuring black-and-white photographs of baseball players to promote its new brand, Play Ball. It became the first widely circulating major national sport card set. The company issued the Play Ball set again in 1940 and 1941 but then stopped due to war rationing.

When sports card production resumed after World War II, the cards became at least as important to companies as the chewing gum. Gum Inc., renamed the Bowman Gum Company, resumed issuing sports cards in 1948 with the first set to exclusively feature basketball, one of the first football sets, as well as baseball and show business stars cards. Over the next two years, Bowman introduced color to its baseball and football cards. Through 1955, Bowman was the only large national football card producer.

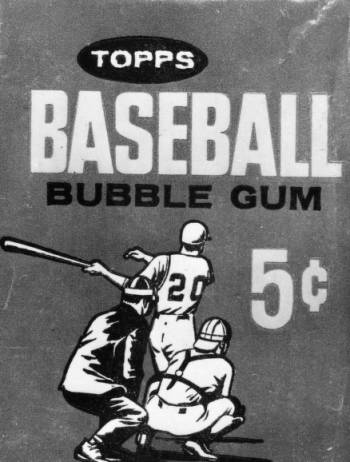

Intense competition for Bowman and subsequent Philadelphia card-makers emerged in 1953, when the Brooklyn-based Topps Gum Company started placing baseball cards with stunning images and detailed information in its best-selling Bazooka Bubble Gum. Bowman sued Topps over infringement of its exclusive contracts with most baseball players and won a precedent-setting ruling that athletes and all celebrities have a “right of publicity.” However, between legal fees and compensation for players, the hobby of card collecting was not big enough to support two card makers. After the 1955 season, Topps bought out Bowman. The Philadelphia plant closed, but the Bowman name continued into the twenty-first century as a popular Topps brand.

With Bowman gone, Fleer reentered the sports card industry. Its chief competitor continued to be Topps, which by 1959 had signed exclusive contracts with every baseball player except aging star Ted Williams (1918-2002). Taking the only baseball option that remained, Fleer created an entire eighty-card set featuring only Williams. From 1960 to 1963, Fleer turned to former stars to produce sets of Baseball Greats, but after that discontinued baseball cards. The firm also had a disadvantage in football, offering American Football League cards while Topps covered the more established and dominate National Football League. Fleer also printed basketball cards for the 1961-62 season, but basketball card sales had always been well behind baseball and football. Forays into cloth “cards” and stickers during the 1960s and 1970s also failed to gain a following among collectors.

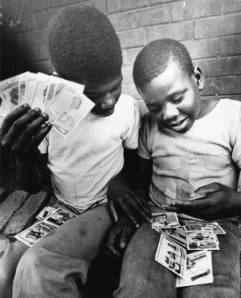

Fleer and Topps also battled in the courts. In 1975 Fleer sued Topps and the Major League Baseball Players Association, accusing Topps of violating antitrust laws by monopolizing the card industry. The case was decided in favor of Fleer in 1980, but then Topps took Fleer to court and won the right to be solely allowed to sell cards with confectionary products. Fleer, the creator of bubble gum, was no longer allowed to sell it alongside baseball cards. It was during this time that sports card collecting as a child or adult’s hobby took off in a major way.

During the early 1980s, Fleer continued as second only to Topps as a producer of sports cards. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Fleer endured multiple ownership changes while the hobby of card collecting also weathered changes and decline. Fleer produced hockey cards until 1996-97 and again from 2001 to 2003 as well as cards for baseball and football. But between the dwindling number of hobbyists and major competition from the dominant Topps and Upper Deck, no room remained for Fleer. The firm declared bankruptcy in 2005, and later that same year Upper Deck bought the brand and name rights. Upper Deck continued the Fleer name as a brand for a variety of sports cards until 2009.

Pursuing innovation and opportunity, Philadelphia companies created not only new products but also a hobby for generations of young sports card collectors. The importance of Philadelphia’s many card producers continued to be evident in the first decades of the twenty-first century in the form of reminiscent “heritage” cards and auctions bringing high prices for the original cards.

Matthew B. Tormey is a political science student at Westfield State University in Massachusetts. For his research into baseball card history he has received a prize from the Pioneer Institute and been published in the American Numismatic Association’s The Numismatist. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History