Thrift

Essay

Philadelphia became a national center for the thrift movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a high concentration of progressive individuals and institutions promoted values of frugality, industry, and stewardship as a means for poor and working-class people to improve their circumstances. Espoused by white middle-class society, the thrift movement declined when the economic roller-coaster of the twentieth century brought an end to the savings banks and school savings banks at the core of assisting individuals in living thrifty lives.

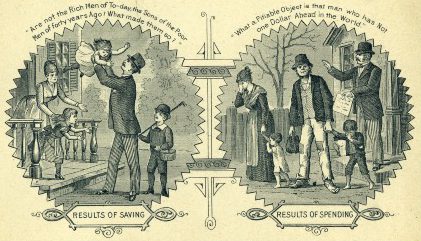

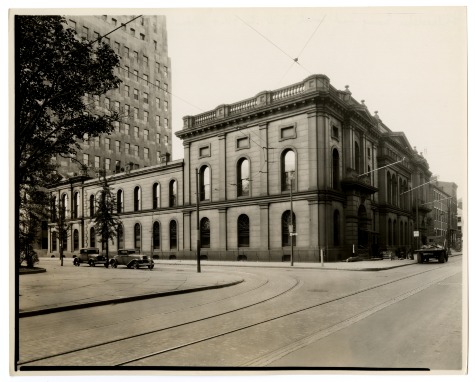

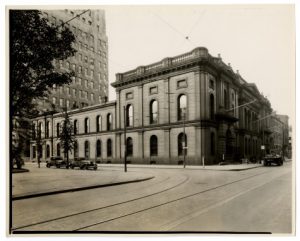

The ethic of “thrift” originated in Europe during the late eighteenth century. Closely aligned with values later called “the Protestant work ethic,” thrift emphasized hard work and strict money saving practices. Private and municipal savings banks were founded throughout Europe. By 1816, Philadelphia had its first saving bank, the Philadelphia Saving Fund Society (PSFS). Along with other savings banks established during the nineteenth century, the Saving Fund Society encouraged individuals to save money for mortgages and retirement and provided a form of economic insurance in case of debilitating illness or the death of a family’s primary wage-earner. This form of institutional savings became popular in the Philadelphia region, where three other savings fund societies formed by 1853, and in other Northeastern states, where nearly six hundred savings banks were in operation by 1930.

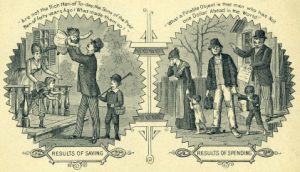

The existence of this type of institution did not guarantee, of course, that people would have the skills or desire to save—or be thrifty. For some, habits could be difficult to change so that saving became a priority over spending money on other luxuries, such as games, alcohol, or tobacco. Some did not trust institutions with their small amounts of hard-earned cash. To inculcate a culture of hard work and frugality, progressive thinkers turned to schools. The Quaker activist Priscilla Wakefield (1750-1832) was the first to organize “frugality banks” for women and children in England during the 1790s. With roots throughout Europe, the idea of teaching children to save through special bank programs was introduced to the United States in the 1880s by John H. Thiry (1822-1911), who then inspired the practice in the Philadelphia area when he spoke to at the American Economic Association hosted by the University of Pennsylvania in 1888.

Sara Louisa Oberhotzer, Zealot of Thrift

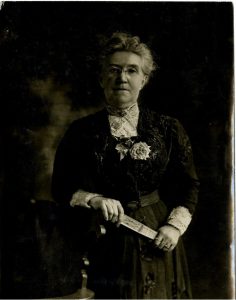

Reformer Sara Louisa Oberholtzer (1841-1930) heard Thiry’s speech and seized upon the concept of thrift. Born into the Chester County Vickers family, she had been weaned on the abolition movement and graduated to temperance, which stressed not only temperance in drink, but also in gaming, the use of tobacco, and dietary habits. The concept of economic temperance as a method to improve the lot of the poor appealed to Oberholtzer, who convinced the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) to take up the cause. As WCTU letterhead later proclaimed, “The inculcation of thrift insures wiser living and decreases pauperism, intemperance, and crime.”

In 1889, Oberholtzer established the first School Savings Banks in Pennsylvania, mainly in towns around Philadelphia, such as Norristown, Phoenixville, Chester, and Pottstown, though there also was one as far away as Wilkes-Barre. Students brought coins to school and “deposited” them with teachers. The schools then transferred their savings into accounts at local banks, under the children’s names. In 1890, Oberholtzer became the national superintendent of the WCTU’s Schools Saving Bank Committee. The same year, fifty schools in Pennsylvania joined as the movement spread to thirty-one cities across the eastern United States.

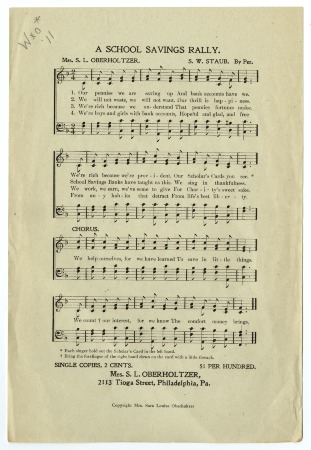

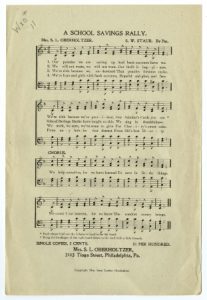

A master marketer, Oberholtzer published articles, books, and pamphlets, including Thrift Tidings, a periodical which ran from 1907 through 1923, and How to Institute School Savings Banks (1913), which sold over fifty thousand copies. She created forms, gathered statistics, and even wrote the School Savings Rally song, complete with accompanying hand motions. At the height of the School Savings Banks movement in the late 1920s, one of every six school students in the country participated in a school-based bank. A school-based essay contest organized by the American Society for Thrift in 1913 received over one hundred thousand entries and was won by a girl from Pennsylvania.

Part of the movement’s success came from its collaboration with educators. The National Education Association established a committee on thrift in 1915 to develop curriculum. In 1917, the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce published Thrift: A Short Text Book for Elementary Schools of Philadelphia. The book was meant for children, probably at the secondary level, but the introduction for teachers reminded adults that forming good saving habits would “make for the success or failure of the city’s enterprises in a decade or two.” The five chapters for the students presented examples of good children who did chores and shopped wisely and, as one chapter title reminded them, to fight against a human desire to “want what we want when we want it.”

Oberholtzer’s ability to garner support from the banking community also contributed to the movement’s success. During the 1910s, the American Banking Association encouraged its members to support the school savings program. In Philadelphia, the venerable PSFS bank took up the cause and continued the program even after school savings banks nationally declined during the Great Depression and World War II from a high of 15,000 in the late 1920s to only 3,500 in 1947. Changes in the banking industry began to impact school savings bank programs. During a last gasp in the 1960s, PSFS in Philadelphia gathered deposits from students, helped them set up school bank branches, and sponsored art contests with the winning entries on display in bank lobbies. The closing of the bank once in the vanguard of the national thrift movement, beginning with a merger in 1982 and culminating in the sale of its assets to Mellon Financial in 1992, ended the systematic incorporation of thrift into local school curriculums, a trend nationwide.

Born during the rise of a cash economy and consumerism in the Atlantic World, the early proponents of the thrift movement desired to help people navigate changing circumstances, but they also imposed their own values about the proper use of money. When Thiry and Oberholtzer introduced school savings banks in the late nineteenth century, they consciously or subconsciously supported efforts to Americanize immigrants, who often lived near poverty in urban areas, into white middle-class society. Changes in the late twentieth century in global economic systems made some institutions of saving obsolete; the subsequent bursting of the tech bubble and recession of 2008 illustrated to many social critics, however, the continued need for teaching thrift.

Beth A. Twiss Houting is the Senior Director of Programs and Services at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. She holds a B.A. in History from Pennsylvania State University and an M.A. from the University of Delaware in the Winterthur Program in Early American Culture with a Certificate in Museum Studies. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Stories from the Archives: The Thrift Movement with Beth A. Twiss Houting (Historical Society of Pennsylvania on youtube.com)

- Teaching Thrift (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- What Chester County native was an ardent supporter of school savings bank? (Historical Society of Pennsylvania Blog Post)

- Women’s Christian Temperance Union History (WCTU.org)

- Philadelphia Saving Fund Society Historical Marker (explorepahistory.com)

- Poet Sarah Louisa Oberholtzer, circa 1882. (explorepahistory.com)