Trade Unions (1820s and 1830s)

Essay

As industrialization began changing the nature of work and society in the United States during the 1820s and 1830s, workers concerned with their low wages, long hours, and the growing power of employers organized to fight for what they believed to be the true ideals of the republic. During this period, Philadelphia workers organized trade unions and supported one of the most spectacular and successful labor demonstrations in the antebellum period, the General Strike of 1835. Although short-lived, their actions had a lasting impact on not only Philadelphia but also the nation.

In the latter half of the 1820s social and economic changes within the United States created a degree of anxiety among free male workers. Questions arose over the direction of the nation, including whether the country had veered away from its founders’ true intentions. Numerous reform organizations attempted to address these concerns, including labor organizations. By the summer of 1827, journeymen in Philadelphia formed the Mechanics’ Union of Trade Associations (MUTA), which became the nation’s first citywide coalition of local unions. The guiding force for MUTA was the belief that the growing power and corruption of business owners and entrepreneurs was increasingly destroying the fabric of the republic. One of the association’s most pressing issues was the movement for a ten-hour work day.

In 1828 MUTA members formed a political organization, the Working Men’s Party, to fight for workers’ rights. The “Workies” polled well in Philadelphia in 1828 and 1829, but internal strife, conservative attacks, and political co-optation by city Democrats who made “workingman issues,” such as debtor relief and militia reform, part of their party platform, brought an end to the political organization by 1831. Its demise left the labor movement in Philadelphia weak, and the collapse of party politics left a bitter taste in the mouths of labor leaders.

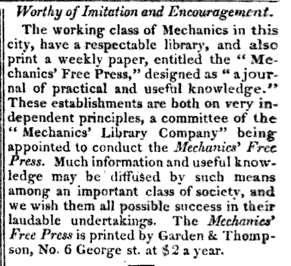

Also in 1827, cordwainer William Heighton (1800-73) began publishing the Mechanics Free Press, one of the nation’s first labor papers, though it lasted just three years. Still, the labor movement of Philadelphia continued to use trade presses throughout the next decade to give voice to the plight of the workingman, focusing on such issues as debtor relief, militia reform, and public education reform.

Conditions Deteriorate

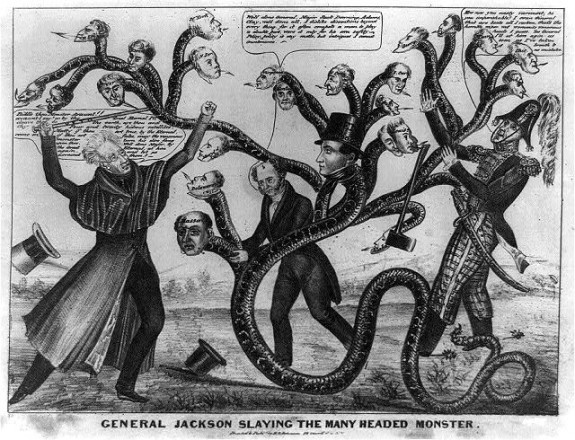

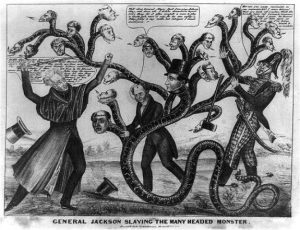

Conditions for American laborers continued to deteriorate in the first years of the 1830s. A war on the Second Bank of the United States waged by President Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) brought a deluge of paper money into the market, issued by a score of state banks, which led to massive inflation. In workplaces, division of labor and increased shop rules and regulations implemented by employers reduced both job security and autonomy to an all-time low. The combination of these forces brought resurgence to trade unionism. Veteran MUTA leaders, such as cordwainer William English, rebuilt Philadelphia’s trade organizations in 1833 by founding the Trades’ Union of Pennsylvania in August, followed by the Mechanic’s Union of Philadelphia in November.

In April 1834, after workers from nine trades in New York City combined to create a General Trades’ Union, labor leaders of Philadelphia organized the parallel General Trades’ Union (GTU) of the City and County of Philadelphia. Structured loosely like the federal government, the organization consisted of five executive officers elected semiannually and a bicameral legislature. Each affiliate union selected delegates to the GTU and had proportionate representation within the assembly, which met weekly and voted on admission of prospective affiliates. Determined not to follow the path of the earlier Working Men’s Party, the GTU steered clear from politics and instead focused on workshop grievances, especially the ten-hour day.

The era’s most impressive and successful general strike followed in 1835. In late May coal heavers at the Schuylkill docks walked off their jobs to protest long hours. Determined to prevent strike-breakers from unloading cargo, nearly three hundred coal heavers paraded on June 3. They were soon joined by cordwainers, carpenters, and other laborers throughout the city who eventually entered and filled the Merchants’ Exchange at Third and Walnut Streets. By the end of the week, more than twenty trades and nearly twenty thousand workers (estimated) were striking, inspired in part by the increasing trade unionism of the city and also by the “Ten-Hour Circular” published by Boston carpenter Seth Luther (1795-1863) during the earlier Boston Carpenters’ Strike.

Led by artisans, such as hand loom weaver John Ferral, workers paraded through the streets of the city accompanied by fife and drum corps and held rallies in Independence Square. They carried banners emblazed with the words “From 6 to 6, ten hours work and two hours for meals.” By June 10 the general strike had essentially shut down the city. Within days, the Common Council announced that workers employed by the city would be granted a ten-hour day. Master carpenters and employing cordwainers soon followed suit. By the end of the month, the ten-hour day, and in many cases increased wages, were granted to workers throughout Philadelphia. In the wake of the strike, interest in trade unionism increased and membership in the GTU soared from roughly two thousand in seventeen affiliates to nearly ten thousand from fifty affiliates.

Solidarity Rises, Then Falls

Trade union solidarity within Philadelphia carried over into 1836. Numerous strikes by such groups as bookbinders and hand loom weavers received guidance and economic support from the GTU. The Philadelphia GTU also became the first trades union in the nation to admit unskilled workers. This occurred in the spring of 1836 when Schuylkill dockers went on strike against coal merchants, who denied them a wage increase. The merchants ultimately won support from Mayor John Swift (1790-1873), who had twelve of the strikers arrested and set their bail at an exceedingly high $2,500. The GTU quickly supported the dockers, admitted them into the organization, and twice paid for their defense in court. The courts ultimately acquitted the workers on charges of breach of peace and conspiracy in restraint of trade.

By the latter half of 1836 the GTU, and trade unionism as whole, began to experience the internal divisiveness that tends to disrupt burgeoning movements. Conflicts over cooperative production, or worker-owned shops, and jurisdictional disputes among affiliates weakened the unity of the GTU. However, the organization’s demise came with the economic Panic of 1837. Trades unions throughout the city lost ground as inflation and unemployment quickened. As unemployment increased workers took whatever jobs that became available; and a staggering number of affiliate trade unions resigned from the GTU Assembly. By 1838, as many of these affiliate unions transitioned into becoming benevolent societies, the main body of the GTU had disappeared, and ultimately the organization dissolved.

Although relatively brief in duration, the labor movement that began in 1827 and climaxed with the General Strike of 1835 brought dramatic long-term changes to the city of Philadelphia. Demands made by laborers during this period raised wider interest in working and living conditions throughout the city, sparked labor presses, and impacted city, state, and national legislation, including the end of imprisonment for debt, Pennsylvania’s Free School Act of 1834, and Ten-Hour Executive Order of 1840 issued by President Martin Van Buren (1782-1862). The General Strike of 1835 and the Philadelphia GTU constituted one of most democratic, yet radical, movements of the Jacksonian Era.

Patrick Grubbs is a Ph.D. candidate at Lehigh University who is writing his dissertation entitled “The Duty of the State: Policing the State of Pennsylvania from the Coal and Iron Police to the Establishment of the Pennsylvania State Police Force, 1866–1905.” He has been employed at Northampton Community College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, since 2009 and has taught Pennsylvania history there since 2011. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Verizon workers strike in Philadelphia (WHYY, August 8, 2011)

- Thousands of Philly janitors may go on strike (WHYY, October 18, 2011)

- Dockworkers' strike could shut 14 East Coast ports (WHYY, August 30, 2012)

- Assessing impact of SEPTA strike on outlying suburbs (WHYY, June 13, 2014)

- Select PHL airport workers strike for money and respect (WHYY, November 19, 2015)

- Union: Strike possible this fall at Pennsylvania's state-owned universities (WHYY, August 12, 2016)

Links

- The formation of the Workingmen's Party of the United States: proceedings of the Union Congress, held at Philadelphia, July 19-22, 1876 (Archive.org)

- General Strike! An American Tradition (pdf, University of Michigan)

- Mechanics' Union of Trade Associations Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Chant of the Coal Heavers: “From Six to Six” (PhillyHistory blog)