Anglican Church (Church of England)

Essay

The Anglican Church came to Philadelphia under the terms of the 1681 Pennsylvania charter, which welcomed all who “acknowledge one almighty God.” In 1695, thirty-nine Anglicans formed Philadelphia’s Christ Church, the first Anglican congregation in Pennsylvania, and requested a minister from the bishop of London, who oversaw the Church of England in the colonies. Members of Christ Church, Philadelphia, joined several Swedish Lutheran churches as the only non-Quaker places of worship in the colony. Facing the dominant Quaker power and the region’s ethnic and religious heterogeneity, Anglicans embraced religious pluralism and a diversity of theological views by their ministers. Anglicans, especially in Philadelphia, vigorously participated in colonial society and commerce, as well as the political debates surrounding the American Revolution (1775-1783). While Anglicans faced unique challenges during this conflict, persons who shifted allegiance to the new state played a pivotal role in the formation of an American Episcopal Church independent from Great Britain.

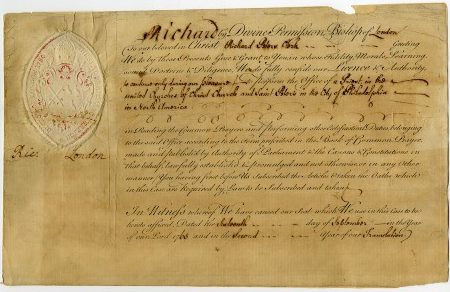

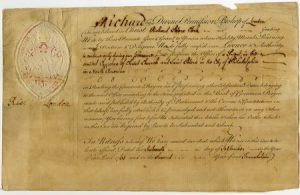

The seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Anglican Church was characterized by its status as a state church, its episcopal governance, and its adherence to the Book of Common Prayer, which contained vital theology and forms of worship that distinguished Anglicans from those outside the church, termed “dissenters.” Early Anglicans optimistically dreamed of recreating the Church of England in the colonies, but only the prayer book existed in Pennsylvania, and colonists looked to the distant bishop of London for guidance and oversight.

Through the 1690s Anglicans in the region complained about Quaker principles and doctrines, including pacifism, refusal to swear oaths, and resistance to most forms of entertainment, and saw Quaker control of the Pennsylvania colony as a threat to orderly society. Their leaders petitioned to turn Pennsylvania into a royal colony and for the appointment of a bishop, and worked to bring “heathen” Quakers back into the true church. By 1695 members of Christ Church Philadelphia erected a small brick church at Second Street and High Street and soon secured a salary from the Privy Council for a minister and schoolmaster. The London-based Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG), founded in 1701, also provided material and financial support to colonial ministers and churches across the colonies. Unlike in colonies where the Anglican Church was established as the state church and local churches were supported by parish taxes, Pennsylvania’s Anglican churches relied on the generosity their members.

Within ten years of Christ Church’s establishment, Anglicans formed congregations in the Pennsylvania settlements of Oxford, Perkiomen, Great Valley, Radnor, Whitemarsh, Marcus Hook, Concord, and Chester. Church officers, vestrymen, and annually elected wardens oversaw church finances and outreach, especially the distribution of moneys to the poor. While eastern New Jersey proved more receptive to Anglicanism, congregations formed in nearby Burlington, Hopewell, and Salem. Churches in New Castle and other communities in Pennsylvania’s lower three counties along the Delaware also operated within the orbit of the region’s oldest Anglican church. Despite these successes, Anglicans failed to convert many Quakers or undermine the Quaker proprietors, and by 1715, Anglicans were forced to acknowledge the legitimacy of other denominations. This enabled them to compete and occasionally cooperate with other religious denominations and sects without the animus that characterized Anglican-dissenter relations elsewhere in the American colonies.

Outnumbered Anglicans

Ethnic and religious diversity often posed a challenge to Anglican outreach; across the region, Anglicans remained outnumbered by dissenters. A lack of missionaries fluent in the language left predominantly Welsh-speaking Anglicans at Trinity Church in Oxford and St. David’s in Radnor with no regular minister until the 1730s. One missionary expressed fear that a Welsh Presbyterian minister would draw congregants from these churches. Anglican cooperation with Swedish Lutherans, whom they viewed as fellow representatives of the “true” apostolic church, was a notable exception. Ministers supplied each other’s pulpits, and several Swedes received Anglican orders or stipends from the SPG to preach in Pennsylvania. However, as a rule, churches remained understaffed and faced near-constant financial uncertainty because of their reliance on donations from individual congregants. By the 1770s seven SPG missionaries served some 1,500 Anglicans in nineteen congregations across Pennsylvania outside of Philadelphia, visiting congregations at least once a month. In their absence, lay members led services from the prayer book.

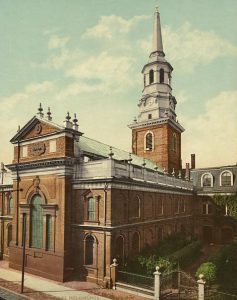

In contrast to rural churches, Philadelphia’s Anglican community grew in pace with the city. Beginning in 1727, members of Christ Church began construction on an ornate new structure modeled on famed English architect Christopher Wren’s Georgian designs, with a brick exterior, the first Palladian window in the colonies, and a steeple, completed in 1753, which contrasted with the modesty of other religious buildings in the Quaker city. Still requiring more space, Anglicans sponsored the construction of a second church, St. Peter’s, which opened on Third Street and Pine in 1761 on land donated by Thomas Penn (1702-1774) and Richard Penn (1706-1771), who had inherited the Pennsylvania proprietorship from their father William Penn (1644-1718) and publicly converted from Quakerism to Anglicanism. To prevent competition between congregations, Christ Church and St. Peter’s remained organizationally united and served by the same ministers until 1832. Architecture, material culture, and music all distinguished Anglicanism from other denominations. Organists at The United Churches, James Bremner (?-1780) and Francis Hopkinson (1737-1791), were the region’s preeminent musicians. Both churches have retained many eighteenth-century features, including box pews, organ cases, and communion silver and a walnut baptismal font, purportedly used by William Penn before his conversion to Quakerism.

Through the mid-eighteenth century Anglican churches struggled with the growing influence of evangelical theology. Lack of oversight also allowed for internal conflicts between clergy and members of the laity, which were mediated by the bishop of London. After the bishop sided with Philadelphia clergymen who opposed the elevation of evangelical SPG missionary William McClenachan (c. 1710-1766) to the United Churches, over a hundred individuals broke away to form St. Paul’s Church, which used the “liturgy, rites, ceremonies, doctrines, and true principles of the Church of England” but allowed the selection of ministers by the congregation without input from the bishop of London. This schism between St. Paul’s and the United Churches ended in 1773 when St. Paul’s asked the bishop to ordain their minister so they could rejoin their sister churches. By the 1770s Anglicans comprised 18 percent of the population of Philadelphia, or approximately 2,500 persons, divided between three congregations. While Pennsylvania Anglicans never gained a resident bishop, their experiences with religious pluralism and diverse theology prompted them to adopt compromises and share power within local churches and the church hierarchy in England.

Elites and Members of Moderate Means

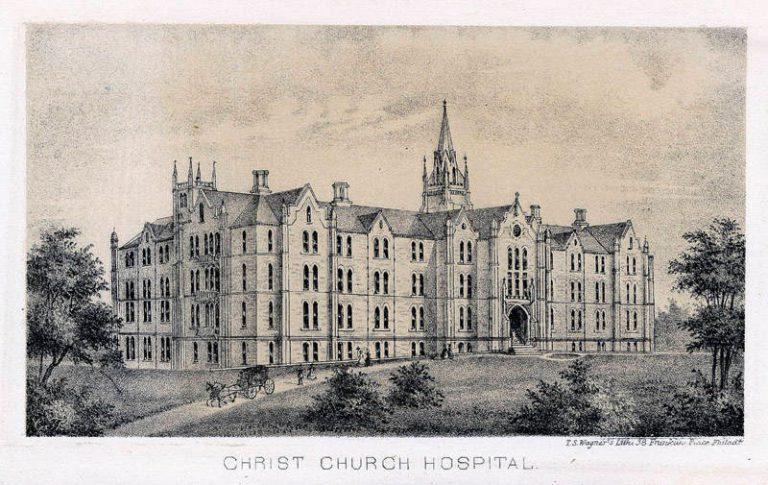

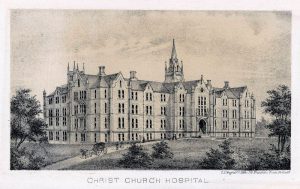

Philadelphia Anglicans represented a cross-section of the city. Leading churchmen participated in voluntary associations, such as the American Philosophical Society, the Library Company, and the Freemasons. Four-fifths of the trustees of the Charity School and Academy, which became the College (and later University) of Pennsylvania, were Anglican, including Richard Peters (1704-1776), who served in numerous posts in the colonial government until 1762, when he retired to become rector of Christ Church. Alongside colonial elites and persons of moderate means, who purchased pews and served as elected leaders, close to a third of congregants numbered among the city’s poorest, and Christ Church routinely provided poor relief to needy persons, especially widows. In 1772, Dr. John Kearsley (1684-1772) founded the Christ Church Hospital (later renamed the Kearsley House), an almshouse that provided for widows and spinsters in their old age.

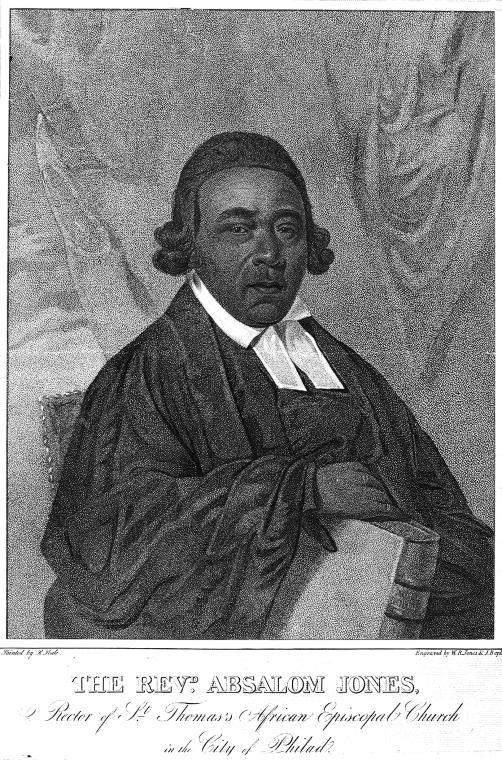

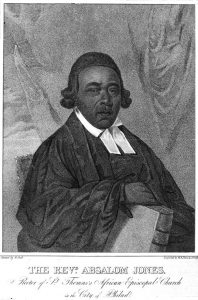

The church also made limited efforts to convert persons of color. In 1746, the SPG provided a stipend for an assistant minister to catechize free and enslaved African Americans. Ten years later, the London-based Bray Associates helped open a school in Philadelphia dedicated to providing religious and practical education to enslaved children. More than 250 free and enslaved African Americans were baptized and over forty couples married at Christ Church and St. Peter’s before 1776. Absalom Jones (1747-1818), who married a fellow slave at Christ Church in 1770, played a major role in the city’s growing free Black community and in 1792 helped found the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, where he was eventually ordained as the first African-American priest in the Protestant Episcopal Church.

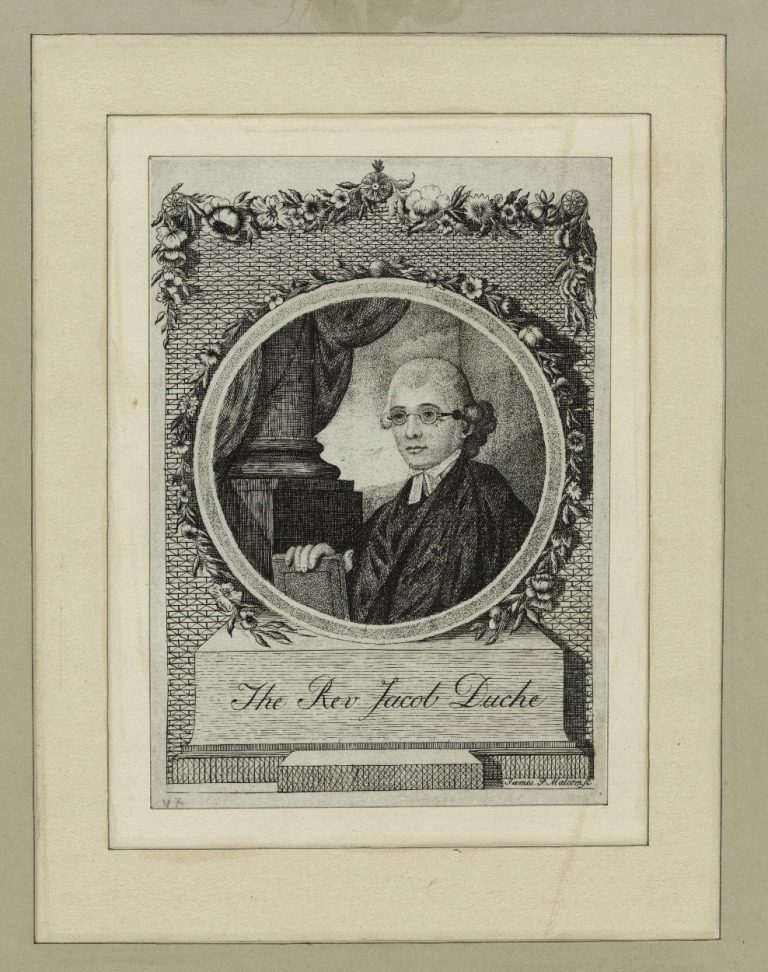

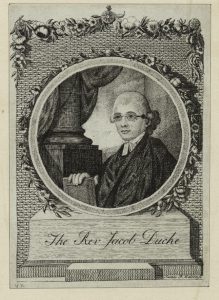

Although lay Anglicans were involved in the political and economic debates of the 1760s and early 1770s, clergymen stayed largely apart from events until September 7, 1774, when Samuel Adams of Massachusetts solicited Christ Church’s Reverend Jacob Duché (1737/8-1798) to open the First Continental Congress in prayer and serve as its chaplain. Adams’s choice of Duché was a deliberate attempt to court the favor of Anglican delegates from influential southern colonies. When war broke out the following April, Philadelphia’s Anglican clergymen remained supportive of the patriot cause. In a June 1775 letter to the bishop of London, they justified their efforts to effect a peaceful and mutually advantageous outcome and remain in good standing with their congregations.

Congress’s Declaration of Independence forced Anglican clergymen to choose whether to disregard their former oaths of loyalty to the crown or close their churches. At a July 4, 1776, meeting, Duché and the vestry decided it “necessary for the peace and well being of the churches” to replace prayers in the liturgy for the king with prayers for Congress. Duché was arrested by the British when they entered the city in October 1777. Accused of treason, he recanted and tried to convince George Washington to sidestep the Congress and sue for peace before fleeing to England. With the exception of the United Church’s assistant minister, William White (1748-1836), who shifted his allegiance to the new country, Philadelphia’s other clergymen similarly fled as loyalists.

Outside of Philadelphia, Anglican clergymen had difficulty maintaining public worship. In September 1776, the Reverend Daniel Batwell of York insisted on reading prayers for the king and was arrested and eventually exiled. The Reverend Thomas Barton (1730-1780) of Lancaster similarly refused to omit prayers and ministered privately to congregants until 1779, when Pennsylvania authorities accused him of “being very instrumental in the poisoning the minds of his parishioners.” Deported to British lines, Barton died before he could depart for England. William Currie (1709-1793) and George Craig (?-1783) who together served five rural congregations, made out better than most. Shuttering their churches, they avoided comparable harassment.

Divided Loyalties

While the majority of Anglican ministers chose exile rather than conforming to revolutionary demands, Anglican laity were divided into loyalists, neutrals, moderate revolutionaries, patriots in favor of radical changes, and persons who underwent changes of heart over the course of the conflict. In Philadelphia, the removal of neutral and loyalist church members who accompanied the British to New York in late 1778 left ardent revolutionaries in control of the United Churches vestry, which remained the lone functioning congregation in Pennsylvania.

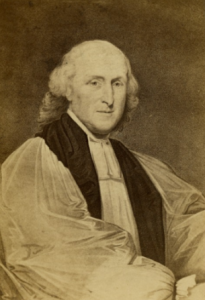

As the war continued, William White led efforts to revive neglected congregations, which after 1784 were organized within the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania. In 1785, the diocese included Philadelphia’s three churches and six rural churches. That year, White helped found the Episcopal Academy in Philadelphia. Originally an all-boys school, it prepared students for the ministry and admission to Pennsylvania College, providing free education for persons with limited means.

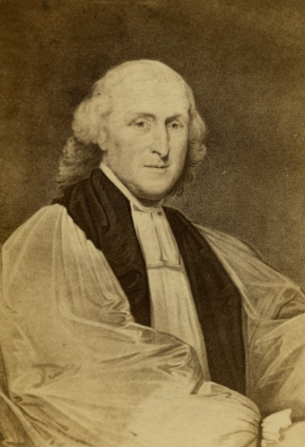

The 1783 peace settlement between the United States and Great Britain prompted renewed debate over the formation of an American Protestant Episcopal Church. In an August 1782 pamphlet titled The Case of the Episcopal Churches in the United States Considered, White proposed modifications to the Book of Common Prayer and altering the episcopal structure of governance to reflect both lay and ecclesiastical representation. Over the next years, deputies to the Pennsylvania Diocese routinely gathered to discuss joining with other Episcopalians, and White helped chart a middle path between the low-church South, which wanted lay control and no bishops, and vocal New England clergy, who catered to ex-loyalists and wanted clerical control and strong bishops. In 1787, White and James Provoost (1742-1815) of New York traveled to England, where they were consecrated as bishops. Finally, in 1789, clerical and lay representatives from nine state dioceses met in Philadelphia and, agreeing on liturgy and governance, created the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America. Because the region’s religious diversity had forced Anglicans to compromise with competitors and operate without state support and limited oversight, Pennsylvania Anglicans were uniquely equipped to operate independent of Great Britain and lead efforts to sever ties with the Church of England.

Ross A. Newton received a Ph.D in History from Northeastern University. His current book manuscript explores Anglicans in colonial and revolutionary Boston, Massachusetts, and their connections within the larger British Atlantic World. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- First Prayer of the Continental Congress by Rev. Jacob Duché (Office of the Chaplain, U.S. House of Representatives)

- Historic Christ Church

- St. Peter's Church

- Historic Philadelphia Tour: William White House (USHistory.org)

- William White Sermons and Documents (Project Canterbury)

- Bishop White House (Independence National Historical Park)

- Religion and the American Revolution (Library of Congress)