Telephones

By Lucy Davis

Essay

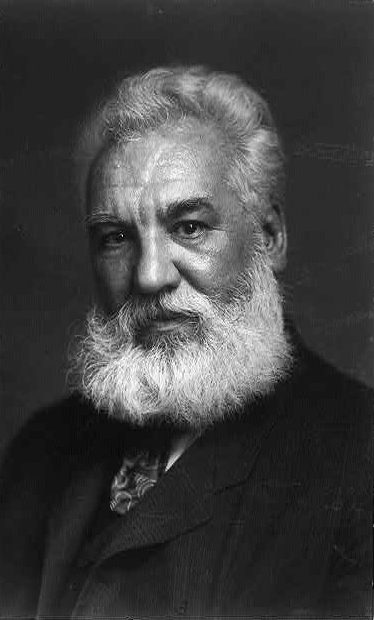

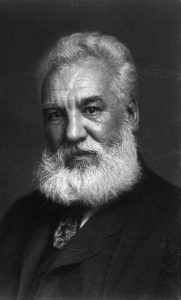

The telephone revolutionized communications by allowing messages to be transmitted instantly to nearly anywhere in the world. Following the public debut of the device at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876, Philadelphia became home to many of telephony’s milestones and a center of telephone innovation, promoted by pioneers and supporters including inventor Alexander Graham Bell (1847-1922) and retail magnate John Wanamaker (1838-1922). The city continued to serve a unique role in telecommunications through the twentieth century with the introduction of the first wireless telephone and the first computer-regulated commercial wireless system.

Before the telephone, long- distance messages could only be rapidly transmitted by telegraph. Invented in 1844 by Samuel Morse (1791-1872), telegraphs used converted messages into Morse Code, which represented letters with a series of short and long taps, conveyed on a transmitting device. Telegraphs became wildly popular, especially with businesses because they provided a written record when the messages were transcribed onto paper. But telegraph technology was not without problems. In addition to requiring operators to be fluent in Morse Code to quickly transcribe messages, only one message could be sent over a single wire at a time. This flaw could delay urgent messages, and several inventors in the latter half of the nineteenth century sought a solution.

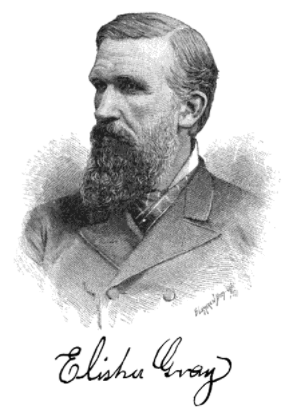

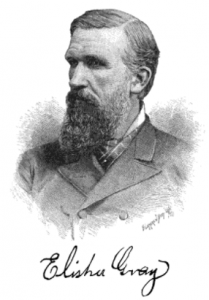

Among the inventors seeking to improve the telegraph, Elisha Gray (1835-1901), an Ohio-based electrical engineer, also discovered a method of transmitting voice over wire using a liquid transmitter. On February 14, 1876, Gray filed a caveat (a legal notice of intent to patent) for his device. Coincidentally, just hours before, Scottish-born teacher for the deaf Alexander Graham Bell (1847-1922) filed a patent for a remarkably similar invention.

Patent Wars

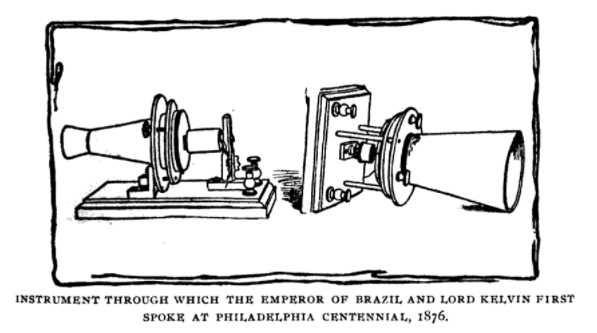

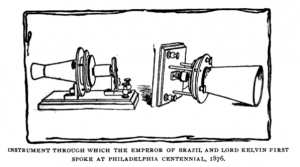

Bell’s invention made its public debut at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, where prototypes were installed at opposite ends of Machinery Hall. After much adjustment, Bell demonstrated the device by reciting lines from Hamlet. Among the many to be amazed by this new technology, Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil (1825-91) reportedly exclaimed, “My God! It talks!” Less impressed was Elisha Gray, who took Bell and his assistants to court over purported patent violations. No technology similar to the liquid transmitter used in Bell’s functioning prototype existed in his notes until March 1876, after Gray filed his caveat. Nonetheless, Bell was awarded the patent and continued to improve on his new device and protect it from would-be competitors.

Philadelphia gained its first private telephone line for practical use in 1877, when Thomas E. Cornish (1838-1924), an electronics supply dealer, founded the Telephone Company of Philadelphia at the request of Pennsylvania Railroad president Thomas A. Scott (1823-1881), who wanted a telephone line installed directly between his home and office. The company and the line were both quickly purchased by Bell. The renamed Bell Telephone Company of Philadelphia established its first headquarters at Fourth and Chestnut Streets.

The first fully functioning switchboard was installed at 1111 Chestnut Street that same year. By then, the telephone was sufficiently developed to allow intercity phone calls, the first of which was made between Philadelphia and New York City. Even more extraordinary, the sound transmitted was not speech but music. Listeners in New York’s Steinway Hall heard pianist Frederick Boscowitz performing in the Philadelphia headquarters of Western Union at Tenth and Chestnut Streets.

The relationship between Bell and Western Union quickly soured, however. Shortly after Bell filed his patents, he had offered them for $100,000 to Western Union, which held a monopoly on telegraph transmission in the United States. Western Union declined, failing to see the commercial viability of such a device. When Bell’s invention proved popular and Bell was unwilling to sell, Western Union hired Thomas Edison (1847-1931) to circumvent Bell’s patent by making slight adjustments to the telephone. Bell sued Western Union for patent infringement, and in 1879 Western Union conceded the patent rights to Bell, creating a monopoly on the telephone industry that lasted for more than a decade.

Early Adopters

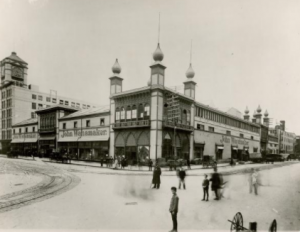

Retail magnate John Wanamaker, a prominent early adopter of the telephone, had a telephone installed in his “Grand Depot” at Thirteenth and Chestnut Streets as early as 1879. By 1906, the store had a telephone ordering system, the first of its kind to allow customers to call in orders. Wanamaker’s system distinguished itself from competitors by allowing customers to order items from the New York City Wanamaker’s store and have then delivered to the Philadelphia location. The service was initially only available to residents of Philadelphia and its suburbs. On December 30, 1911, a special long- distance telephone device allowed customers in the New York Wanamaker’s store to hear the grand opening ceremonies for the new Philadelphia store, including a performance of the “Triumphal March” from the opera Aida on the famed Wanamaker Organ.

Other early adopters of the telephone included businessmen, physicians, and druggists, who valued the instantaneous nature of telephone transactions. But home and personal use remained low until well into the twentieth century. Many people failed to see the purpose in using the device for social calls, and most advertisements were directed toward business owners. In Philadelphia, Bell began with only fifteen customers in 1877 and had only 3,300 in 1890. But the practical use of the telephone soon proved it indispensable. By 1917, there were 175,000 Bell Telephone subscribers and 450,000 miles of telephone wire in Philadelphia.

Bell’s patent on his telephone system ended in 1894, and competitors quickly emerged. In 1900, a U.S. Representative from Pennsylvania, Robert H. Foerderer (1860-1903), founded the Keystone Telephone Company, launching a rivalry that spanned nearly fifty years. Keystone never approached Bell in size, but it used this to its advantage in marketing its service to consumers. Keystone operated only seven telephone exchanges at its peak and could assign one number to each exchange. As a result, Keystone telephone numbers were only five digits long, one for the exchange and four for the extension, as opposed to the more common seven digit numbers used by Bell. Print advertisements highlighted this feature, billing Keystone’s as “the fastest telephone in Philadelphia.” Keystone telephones were manufactured with exchange numbers printed on their rotary dials to further facilitate speedy dialing.

Bell and Keystone competed for the market across the Delaware River as well. In 1902, the Eastern Telephone and Telegraph Company completed a cable under the Delaware River connecting its lines to Keystone’s system in Philadelphia. Keystone later bought out Eastern as well as a number of smaller communications companies. The first interstate automatic telephone exchange was introduced in Philadelphia in 1943, but this service was not extended to South Jersey customers. Philadelphians wishing to reach Camden residents from Keystone lines were still instructed to speak to operators at manual exchanges.

The two companies continued to compete fiercely, even building exchanges across the street from one another, until Bell bought Keystone in 1944. Keystone service ended on September 17, 1945. At the time, Philadelphia was the only major American city with two competing telephone service companies. In the Wilmington, Delaware, area, service originally provided by the Atlantic & Delaware Telegraph Company was purchased by Diamond State Telephone Company, a subsidiary of Bell. Bell again effectively created a monopoly on telecommunications in the United States that which remained in place until January 1, 1984, when the Bell System was broken into seven “Baby Bell” companies. Philadelphia customers came under the control of Bell Atlantic, which merged with Connecticut-based GTE Corporation in 2000 to form Verizon Communications.

The Dawn of Wireless Telephony

Philadelphia was home to some of the early milestones of mobile telephony. In 1919, W. W. MacFarlane of Elkins Park, Montgomery County, invented a portable wireless telephone in his home workshop. Weighing twelve pounds and with a range of just one-quarter mile, the device was hardly practical and just barely portable. Nevertheless, MacFarlane’s invention generated interest among hobbyists when he demonstrated it by taking reporters for a ride in his automobile, then calling his wife at home.

MacFarlane envisioned that mobile telephony would soon be in use on railroads. It would be another fifty years, however, before this prediction came true. In January 1969, the first commercial cellular radio system was designed by Bell Systems for Penn Central Railroad’s high-speed Metroliner service between New York City and Washington, D.C. The system was managed by a computerized control center located in Philadelphia’s Thirtieth Street Station.

The first consumer mobile phone did not enter the market until 1983, when Motorola released its DynaTAC, colloquially known as the “brick phone.” As with telephone service in its early days, the mobile phone was initially successful only amongst business owners and professionals, but eventually became almost universal. In 2015, a Pew Research Center survey found that 92 percent of U.S. adults owned a cellular telephone. Philadelphia continued to play an important role in telecommunications in the twenty-first century. Although Bell left the city in 1997, Philadelphia became the home of Comcast, one of the largest providers of telephone landlines. Once a novelty, the telephone became an almost indispensable technology for both business and social communication. The telephone companies that called the region home helped the Philadelphia area become a center for telecommunications businesses and innovation.

Lucy Davis is a research and digital publishing assistant for The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publishing.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- NJ's Bell labs says it can shrink those wireless phone antennas (WHYY, March 2, 2011)

- 'Icing' your phone could save a life (WHYY, January 13, 2014)

- Is your phone giving you the flu? (WHYY, January 16, 2014)

- In Philly, 'bat phone' helps unemployed connect with understaffed office (WHYY, April 20, 2017)

Links

- Wired City (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Alexander Graham Bell's Large Box Telephone (Smithsonian Institute)

- Alexander Graham Bell Experimental Telephone (Smithsonian Institute)

- Wyoming Central Office of Bell Telephone Nomination (pdf, National Register of Historic Place)

- Telephone & Light Patent Drawings (National Archive)

- A North Philly Building's Direct Connection to the Past (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Dial Up for the Latest Election News (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The Invention of the Telephone Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)