Shoemakers and Shoemaking

Essay

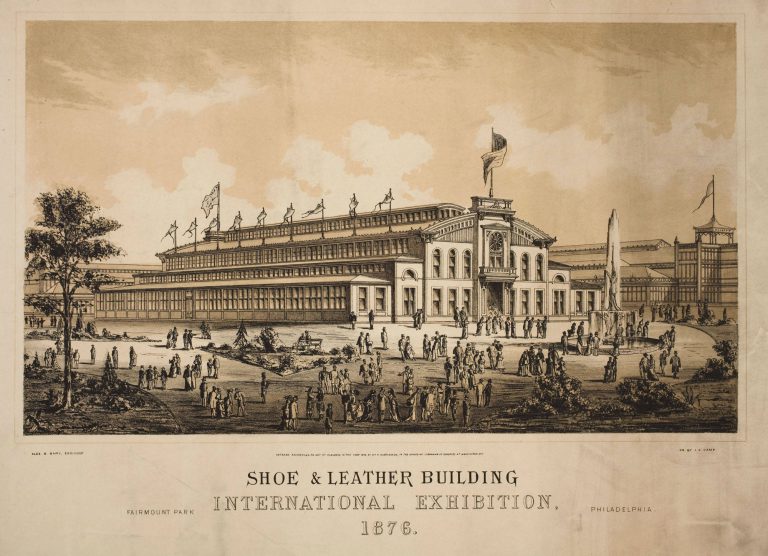

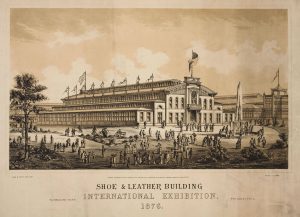

One of Philadelphia’s oldest occupations, shoemaking grew in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to become one of the city’s leading industries. During that period shoemakers in Philadelphia also became some of the leading figures in the city’s, and the nation’s, burgeoning labor movement. The methods and institutions that these leaders used throughout the nineteenth century made Philadelphia one of the nation’s most active labor centers, laying the foundation for labor organizing for years to come.

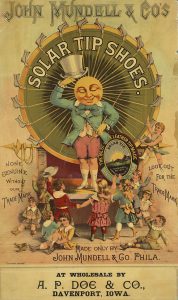

Known also as cordwainers, a term from the Middle Ages used to describe someone who worked with Spanish leather made at Cordova, Philadelphia shoemakers grew from only a handful in the 1680s to over three hundred by 1774. Demand rose in response to the preference among colonists not to rely on the arrival of European goods as their primary source for footwear. The trade continued to expand throughout the eighteenth century, and by the early 1770s Philadelphia became a center for shoemaking, not only for neighboring colonies, but also for the West Indies.

This reliance on domestic production brought increased social status to Philadelphia’s cordwainers, a position they fought hard to protect throughout the eighteenth century. Faced with outside competition, in 1718 master cordwainers and tailors presented a joint petition to the Common Council of Philadelphia, seeking to protect their crafts within the city. While the Council failed to sanction what would have constituted a guild, cordwainers succeeded in creating such a de facto status for themselves in 1760 with the establishment of the Cordwainers’ Fire Company. Firefighting was the organization’s primary objective, but its limited membership and benefits, limited to thirty craftsmen who had served a regular apprenticeship, and the special fund created to assist in the apprehension of runaway apprentices, served as a way to insulate and concentrate the master cordwainer community.

Shoemaking continued to be one of Philadelphia’s most populous and lucrative trades throughout the eighteenth century. The craft not only contained the largest number of apprentices of any trade throughout the city, but also made up one the largest units during the 1788 Grand Federal Procession, with over three hundred participants. Due in part to expanding markets and building from ideals that began with their fire company, in 1789 master cordwainers formed a society designed to regulate their business and to protect their craft. The main objective was to prevent shoemakers within the city from advertising their prices in pamphlets or newspapers or selling their goods at public markets. The collective interest of master cordwainers now carried beyond the Revolutionary era as they sought to control competition in the market and to prevent the underselling of goods.

The Master-Journeyman Relationship

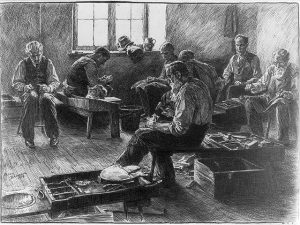

Traditionally the relationship between the master, who owned the shops, oversaw production, and trained their workers and journeymen, graduated apprentices who labored for wages under nominal supervision with the aspiration of obtaining master status, was one of mutual obligation and respect. Contention between masters and journeymen was not overtly apparent by the early 1790s. For example, in 1791 when a pair of outsiders set up shop in Philadelphia, advertised their prices in city newspapers, and attempted to undersell established cordwainers, both masters and journeymen fought their presence. However, while the masters and journeymen both challenged underselling, which affected both profits and wages, they did so as separate entities, showing early signs of dissension within the craft.

That dissension increased throughout the 1790s as journeymen societies grew within the craft. Once master artisans moved away from the workbench and sought markets outside of Philadelphia, journeymen saw their chances of reaching master status dwindling. Increasingly they viewed their goals within the craft as different from those of the masters.

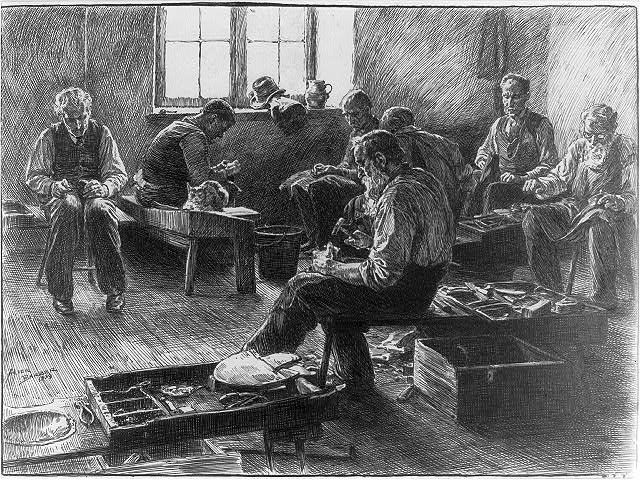

It was during this period that the shoemaking process began to change. No longer was the product produced by a lone artisan. Mechanization did not impact the shoe industry until the mid-nineteenth-century, but increasingly owners used division of labor and outwork, sending parts of the shoe to be manufactured at home in an effort to increase the pace of production. Master shoemakers, such as John Bedford, began to produce for the larger market, instead of the community and aspired to gain increasing profits, not just competence. Bedford originally owned a small shop located at the corner of Gratzmere and Second Street. As his business grew, he moved his shop to the corner of Ingles and Second Street. Ultimately, he obtained a patent ironbound shoe store and warehouse at Market Street near Ninth Street and began to take orders for boots and shoes in the South. However, when Bedford returned from Charleston with an order of over $4,000, journeymen laid down their tools as they demanded a wage increase for the products to be produced for export. This strike not only halted production, but ultimately forced Bedford to default on a number of orders.

As journeymen societies grew throughout the 1790s they were increasingly successful at gaining wage increases and preventing ”scab workers,” those who agreed to work for lower wages, from entering the trade. In 1799 more than one hundred journeymen walked out when master cordwainers attempted to reduce their wages. The journeymen returned to their benches quickly, however, after an agreement between the two parties reduced the rate deduction to half its original size. Calm existed between the two groups for a half decade but their next clash proved to be one of the most significant moments in nineteenth-century labor history.

A Demand for Higher Wages

In the fall of 1805 journeymen laborers demanded a wage increase not only for export goods, especially those produced for southern markets, but also for the production of expensive boots, which took longer to make. The master cordwainers quickly rejected their petitions. The nearly seven-week strike that followed proved unsuccessful for journeymen shoemakers, as they were ultimately forced to return to their benches at the previous rate. The strike officially came to an end when master cordwainers, including John Bedford, tired of the constant dissension within their craft, took the issue to court. In November 1805 eight journeymen shoemakers were indicted by a Philadelphia grand jury on charges of combining and conspiring to raise wages.

The trial that began the following spring, known as The Commonwealth v. George Pullis, proved to be one of the most influential labor trials in the nineteenth-century. Master cordwainers argued that journeymen societies had formed illegal combinations designed to exact wage increases from employers. More importantly, they argued that the presence of these institutions was a threat to the social and economic stability not only of the city, but also of Pennsylvania as a whole. Due in large part to the presence of Federalist Judge Moses Levy (1757-1826), who proved sympathetic to the master cordwainers, the eight journeymen were ultimately found guilty of illegal combination and conspiracy and were each fined eight dollars. This court case ultimately established a precedent that outlawed collective action by laborers, such as labor unions, and was cited in similar cases throughout the industrial Northeast over the next thirty-five years. The precedent was not overturned until 1842.

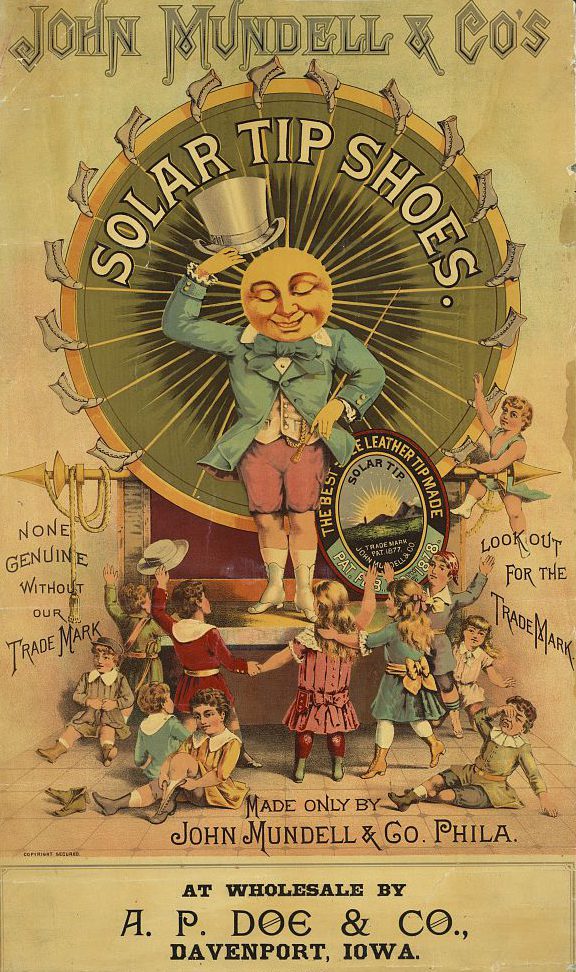

Throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century, shoemaking continued to be one of the most populous professions within the city, while it also provided some of most influential labor leaders in Philadelphia’s history. As the link between master artisans and journeymen devolved into a relationship between business owners and wage earners, conflict within the trade revived. In 1827, cordwainer William Heighton (1800-73) began publishing the Mechanics’ Free Press, one of the nation’s first labor papers, and helped establish the Mechanics’ Union of Trade Associations (MUTA). In 1828 MUTA leaders, including cordwainer William English, formed a political organization known as the Working Men’s Party to fight for workers’ rights. English continued his work on behalf of Philadelphia laborers by founding the Trades’ Union of Pennsylvania and Mechanic’s Union of Philadelphia in August and November 1833, respectively.

Labor Momentum Ebbs Then Grows

From the Panic of 1837 through the end of the Civil War, labor movements throughout the city and nation lost momentum. Economic depression, nativist politics, and the secession crisis distracted many laborers from the fight for workers’ rights. However, during the last four decades of the nineteenth century shoemakers once again led Philadelphia’s labor movement.

Primary in that stage of organizing was shoemaker Thomas Phillips (1833–1916), who arrived in Philadelphia in 1852 and immediately became active in the city’s labor movement. Throughout the 1850s and 1860s Phillips took the lead in organizing the city’s shoemakers, pushing for an eight-hour day and the establishment of cooperatives. In 1869 he helped establish the Philadelphia lodge of the Knights of St. Crispin, a craft union that began in Milwaukee in 1867. In the early 1870s he became the first shoemaker to join the Knights of Labor and established Local Assembly 64 of that order, the first assembly of shoemakers in Philadelphia. In the late 1880s a rift developed between shoemakers and the Knights of Labor when it refused to support an 1887 strike. The following year Phillips orchestrated the shoemakers’ exit from the organization, becoming the same year the first general president of the newly created Boot and Shoe Workers’ International Labor Union, an affiliate of the American Federation of Labor. Phillips grew disgruntled with the lack of support he received as general president, including the organization’s unwillingness to pay his expenses for trips required by the union, and he left the labor movement altogether in 1890.

Shoemaking had one of the longest and most active histories of any trade within the city of Philadelphia. While the trade itself flourished throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the labor strife and the labor leaders that emerged from the trade proved to have a lasting impact on this period of Philadelphia’s labor history. From the conspiracy trial of 1806 through the end of the nineteenth century, shoemakers led the fight for workers’ rights, not only in the city, but throughout the nation.

Patrick Grubbs is a Ph.D. candidate at Lehigh University who is writing his dissertation entitled “The Duty of the State: Policing the State of Pennsylvania from the Coal and Iron Police to the Establishment of the Pennsylvania State Police Force, 1866–1905.” He has been employed at Northampton Community College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, since 2009 and has taught Pennsylvania history there since 2011. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University