Clocks and Clockmakers

Essay

Clockmaking in colonial and early republican Philadelphia and its environs was considered an intellectual profession requiring great artisanal skill and scientific knowledge. Among rural communities surrounding the city, the mathematical precision and mechanical intricacy of the profession put it at a superior rank to the crafts of blacksmithing and carpentry. Clockmakers like David Rittenhouse (1732-96) and Edward Duffield (1720-1801) garnered respect comparable to the likes of political leaders Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) and Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826). The combination of science and craftsmanship made the design, assemblage, and manufacture of clocks a first profession for many scientists and statesmen of distinction.

Before 1750 the majority of clockmakers in the colonies were trained in England. However, Pennsylvania in particular became noted for the influence of German designs on its clock production. Although English Quakers dominated Philadelphia, William Penn’s “holy experiment” attracted tens of thousands of settlers from Germany, Switzerland, and Ireland. These immigrants included many skilled artisans from northern Europe, including clockmakers, making Pennsylvania a prime site for producing high-quality clocks.

One of the earliest clocks to make its way to the Philadelphia region was the “Dial of Ahaz,” named after the King of Judah who supposedly invented the sundial in the eighth century B.C.E. The Ahaz sundial was made by Christopher Schissler (ca. 1531-1608) in Germany in 1578 and arrived some time before 1700 with a mystical religious group known as the Pietists or the Hermits of the Ridge. This group, dissatisfied with Protestant and Catholic ritual and led by Johannes Kelpius (1667-1708), came to Pennsylvania in 1694 and settled in Germantown. The group’s interests in mathematics and the astronomy used to calculate the time of the millennium made them prime candidates for clockmaking.

The Eminent Christopher Witt

An entire school of clockmakers trained under another Pietist, Christopher Witt (1675-1765), who arrived in Germantown in 1704 and began making clocks as early as 1706. It is believed that Witt gave the Dial of Ahaz to Benjamin Franklin as a gift. Witt went on to apprentice another important clockmaker in the German tradition, Christopher Sauer (1695-1758). A brass dial, tall-case clock made by Sauer around 1735 became the earliest American-made clock in the collections of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

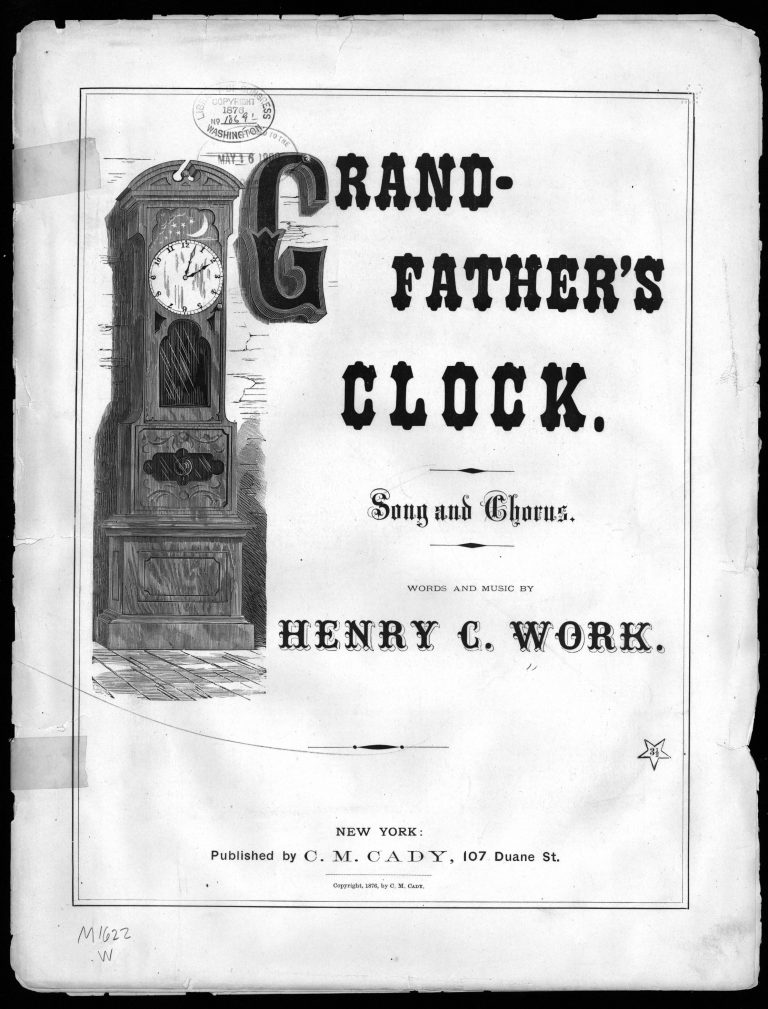

Pennsylvania clock production was set apart from New England by the high quality and individual construction of the tall case clock, a design that consisted of parts often made separately in England, France, and America. These included a case, dial, and mechanism and required collaborative work among cabinetmakers, iron founders, engravers, braziers, ornamental painters, and mathematicians. The weight-and-pendulum design housed in a tall case became known as a “grandfather clock,” the name of which can be traced to a Philadelphia songwriter. In 1876, Henry Clay Work (1832-84) wrote these lyrics: “My grandfather’s clock was too tall for the shelf so it stood twenty years on the floor.” In Pennsylvania, clocks were a symbol of family and stability, often passed down as important heirlooms through generations.

Businesses and government relied on clocks to facilitate meeting times and to regulate working hours. As business and trade increased, the variability of watches necessitated the construction of a public clock. The first of these in Philadelphia was housed in the old courthouse built in 1710 at Market and Second Streets. Made by English clockmaker Peter Stretch (1670-1746), the device told time aurally by ringing a bell.

As the city grew and the center of town shifted farther west, Philadelphia needed a new public clock. According to legend, Benjamin Franklin asked his friend Edward Duffield to make a clock for public display after growing tired of being constantly stopped by workmen on the street wishing to know the time. At this time, personal watches were still a luxury item. Duffield’s clock hung outside his shop at Second and Arch Streets from the 1740s until the Revolutionary War. In 1753, a new public clock was installed at the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall). The clock faces on the building’s east and west gable ends were made by Peter Stretch’s son, Thomas (1697-1765). It was not until 1828 that a clock designed and constructed by Isaiah Lukens (1779-1846) and Joseph Saxton (1799-1873) was installed in a new tower, built to replace the long-demolished original.

David Rittenhouse

When David Rittenhouse moved from Germantown to Philadelphia in 1770, clock making continued to be his chief source of income. Rittenhouse made approximately seventy-five clocks in his lifetime and, in a distinctly Pennsylvania tradition, each was unique. Thomas Jefferson described one Rittenhouse orrery, a mechanical model of the solar system, as “a machine far surpassing in ingenuity of contrivance, accuracy, and utility, anything of the kind ever before constructed. …He has indeed made a world, but by imitation approached nearer its Maker than many man who has lived from the creation to this day.” The orrery’s clockwork mechanism represented a view of an orderly, clockwork universe, something essential to the values and ideals of the new republic.

By the 1820s clocks ceased to be a luxury item and became so common that they were considered just another piece of household furniture. Around 1835, the Pennsylvania tall clock began to be supplanted by the cheaper, mass-produced New England shelf clock. Consequently, the definition of “clockmaker” began to shift. Various individuals who had no part in the final construction of a clock and who had no knowledge of its mechanisms could separately manufacture individual parts. Under this division of labor, a clockmaker referred primarily to a tradesman who polished a clock’s teeth and steel parts and adjusted the mechanism to maintain accurate timekeeping.

While mass production of clocks flourished in New England, Philadelphia, New Jersey, and Delaware remained known for a tradition of artisanal clocks of the highest quality and individual character. In Delaware, between 1740 and 1840, forty-five clock and cabinetmakers had establishments in Wilmington alone. In New Jersey, notable clockmakers included Isaac Brokaw (1746-1826) in Elizabethtown and Aaron Dodd Crane (1804-1860) in Newark. Brokaw was known for his handcrafted clock pieces, down to the hand hammering of brass dials. Crane published several patents for improving clock mechanisms and the market for his clocks extended as far as New York and Boston. These tall case clocks illustrated and reflected the diverse and collaborate nature of the wider Philadelphia region’s artisanal and scientific communities.

Influence of Mass Production

With the proliferations of mass-produced clocks and smaller, inexpensive watches at the beginning of the twentieth century, artisanal clock production slowed. However, public clocks continued to play an important role in shaping the landscape of Philadelphia. The synchronization of time became necessary to coordinate and regularize the flow of rail travel, leading to the 1893 implementation of Standard Railway Time across the United States. Public clocks in Philadelphia could be seen at its many transportation hubs, including the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Broad Street Station built in 1881. In 1892, a twenty-one-foot Victorian-style clock stood at Broad and Chestnut Streets in front of the ticket office for the Reading and Baltimore & Ohio Railroads. After being moved to Twelfth and Chestnut Streets in 1901, the timepiece was nicknamed “Lover’s Clock” since it was used as a meeting place for couples on dates.

Public clocks dramatically shaped the iconography of Philadelphia’s skyline. The city’s most iconic timepiece, the fifty-ton clock at City Hall, 362 feet above Broad and Market Streets, was the largest and highest in the world when installed and put to service at midnight December 31, 1898. Time could be determined from approximately a mile away, allowing citizens to adjust their home clocks to official Philadelphia time. The 150 incandescent light bulbs that illuminated the clock were originally bright white. By the 1940s, the plate glass of the clock faces were yellowed by sulfurous coal smoke, producing the now-iconic amber glow of the City Hall clock. In 1963, the city officially changed the cleaned bulbs to a tinted yellow color, creating the most recognizable fixture of the Philadelphia skyline. Several blocks north on Broad Street, the four-faced clock atop the Inquirer Building, the tallest building north of City Hall when constructed in 1924, could be seen from miles away. Even after cheap wristwatches and cell phones replaced the need for the manufacture of clocks, the public clocks of Philadelphia continued to define the city’s landscape and iconography.

Michelle Smiley is a Ph.D. candidate in the History of Art at Bryn Mawr College. Her dissertation considers the history of photography and its technological development in the United States. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- The Rittenhouse Orrery at the University of Pennsylvania Library, Philadelphia, PA (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Detail of the Rittenhouse Orrery, University of Pennsylvania library, Philadelphia, PA (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Public Clock Still Keeping Time On Philly’s Streets (At Least Twice A Day) (Hidden City)

- Is Independence Hall Tower in Sync with History? (Philadelphia History Blog)

- Doomsday Cult on the Wissahickon (Hidden City)

- My Grandfather's Clock (Eduteach)