Dogs

Essay

For as long as people have inhabited Philadelphia and the surrounding area, dogs probably have been present, too. As the first domesticated animal, dogs possess a long, complicated past with humans, likely dating back between fifteen thousand and thirty thousand years. Domesticated canids accompanied human migrants to the Americas around 10,000 to 12,000 BCE. Over many millennia, they have served crucial roles in the region as workers and companions, as muses for stories, and in countless other capacities.

Archaeological sites throughout the northeastern United States reveal that Native Americans used dogs in sacrifices, as partners in the hunt, and as spiritual guardians. Early inhabitants of the Delaware Valley, the Lenni Lenape, believed that dogs guarded passage through the heavens and only permitted virtuous souls to join the creator in the afterlife. Burial sites throughout eastern Pennsylvania containing artifacts carved with dog motifs attest to the close link believed to exist between dogs and the spirit world.

European immigrants to the Philadelphia region valued dogs for their utility and labor. Colonists employed greyhounds, bloodhounds, and nondescript mixed breeds to track game. Often these excursions supplied food for the table, but in other instances an emerging gentry utilized packs of hounds to pursue foxes for sport. Other dogs kept vigil over livestock and property. Occasionally, some advocated for the use of mastiffs and other large breeds as weapons of war against native peoples. In 1755, Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) called for Pennsylvania to acquire fifty mastiffs to harass Native Americans allied with the French during the Seven Years’ War (1756-63). (No evidence suggests that Pennsylvania acted upon Franklin’s suggestion.) Dogs also served as beasts of burden, especially among the working class who lacked the resources to invest in horses. Occasionally, entrepreneurs envisioned dogs as engines of industry powering turnspits, churns, or other mechanical devices. At an agricultural exhibition on the Bush Hill estate in Philadelphia in 1822, one enterprising man demonstrated a system in which four dogs on a treadmill generated the requisite energy to power a grist mill.

Growing Affection

In spite of the fact that relationships were often grounded in specific acts of labor and utility, tender feelings and strong connections still flourished between master and dog. The Philadelphia family of Elizabeth Drinker (1735-1807), for example, possessed many dogs through the years, and her diary revealed genuine attachment to the animals. When her “good old Dog, Watch” died in April 1781, she recalled that he had “served us faithfully for upwards of seven years.” Poems and odes praising the steadfast loyalty of watchdogs appeared frequently in journals and illustrated the attachment that people fostered toward their companions. In addition, newspaper advertisements throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries announced rewards for lost dogs of all kinds.

Although dogs proved to be valuable assets for their owners on many levels, their increasing numbers created problems in the city. As early as 1702, a grand jury in Philadelphia complained of “the great damage the Inhabitants of the Citty Do Dayly sustaine by the great loss of their sheepe and Dammage by Reason of the Unnecessary Multitude of Doggs that are needlessly kept in the Cityy.” Even as the United States remained overwhelmingly rural well into the nineteenth century, dogs became an enormous nuisance in cities. Since many owners permitted their pets and livestock to range freely, dogs charged after carriages and knocked down pedestrians. Snarling curs infested markets and their waste blanketed doorsteps and sidewalks. After the sun went down, a chorus of howls often prevented citizens from getting much-needed rest. Perhaps most importantly, the press raised the specter of “mad dogs”—aggressive and unpredictable canines that were ostensibly afflicted with rabies. While rabies (or hydrophobia as it was known at the time) was an extremely rare disease, newspapers amplified its presence by printing graphic accounts of the excruciating deaths of its victims. The threats posed by dogs convinced one correspondent to a Philadelphia newspaper to remark in 1811, “To walk through the city after the close of day has become truly dangerous … it will soon become necessary, for those who would ensure safety, that they go armed.”

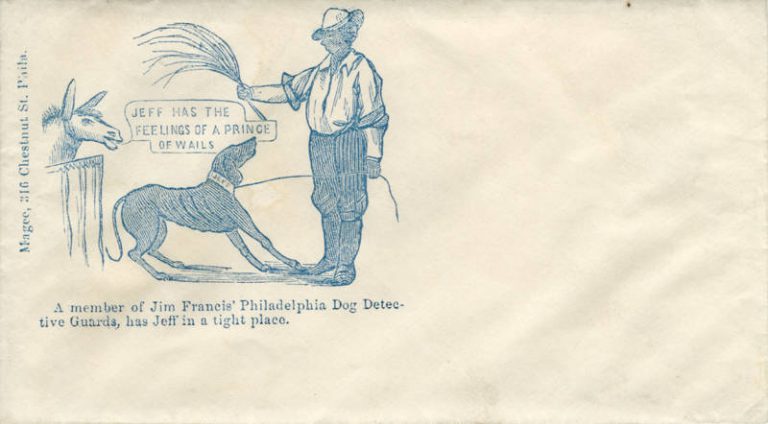

As a result, Philadelphia, like many major cities in the nineteenth century, embarked on a program to regulate the numbers of dogs that roamed the streets. Residents called for heavy taxes on dogs as well as legislation that required roving canines to be equipped with collars and muzzles. Municipal governments implemented ordinances and enlisted dogcatchers to capture strays and destroy the surplus population. Beginning in the 1850s this less-than-desirable job fell to a group of African Americans who became known in the press as the Dog Detectives. Between June and September each year, the Dog Detectives, led by Captain Jim Francis (?-1864), corralled dogs found without muzzles and delivered them to a pound, located for a time on Buttonwood Street between Broad and Thirteenth Streets. There, Francis and his associates clubbed the dogs to death if owners failed to claim their pets and pay the requisite fine within a day or two. Generally, Philadelphians found the work of the dogcatchers barbaric, but newspapers frequently praised their efforts in the name of public health and safety.

Humane Treatment Movement

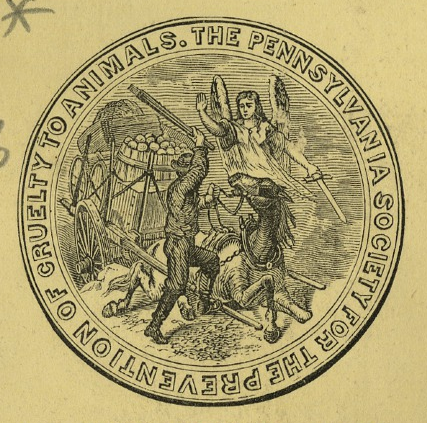

In the middle of the nineteenth century, a growing impulse emerged to view animals as sentient beings worthy of protection from abuse and neglect. Americans cultivated what became known as a domestic ethic of kindness and lobbied for the humane treatment of creatures unable to fend for themselves. In 1867, the Pennsylvania Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (PSPCA) became the second anti-cruelty organization in the nation. Chapters followed in New Jersey in 1868 and Delaware in 1873. The Women’s Branch of the Pennsylvania Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (WPSPCA), founded in 1869, made the treatment of dogs one of its top priorities. Under the guidance of Philadelphia humanitarian Caroline Earle White (1833-1916), the WPSPCA worked to provide shelter and placement in new homes for lost and unwanted strays. For those too sick or old to be adopted, the WSPCA instituted a new method of putting animals to death with the use of carbonic acid gas. The compassion of the women earned the respect of many for removing the cruelty and violence that had been embedded in the process of capturing strays for decades.

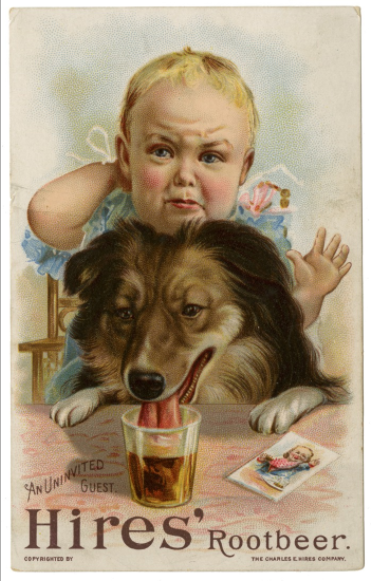

At the same time, changing attitudes toward animals led to increased pet ownership among the middle class. Philadelphia held what was billed as the first extensive dog show in the country at the Centennial Exhibition in September 1876. Fanciers exhibited nearly six hundred canines from diminutive toy black-and-tan terriers to lean Italian greyhounds and massive Newfoundlanders. The emergence of exotic breeds and the dog shows that publicized them increased the popularity of many novel types of dogs and transformed them into commercial objects and status symbols. Throughout the late nineteenth century, once exotic and rare breeds like the spitz, pug, Boston terrier, Scotch collie, and Saint Bernard fell in and out of fashion. With people’s attachment to their dogs reaching new levels, consumers sought out a wide array of products designed for their pets including food, leashes, blankets, and beds.

In the twentieth century dogs became ubiquitous in the role of faithful companions. The animals’ gregarious nature enabled them to insinuate themselves into new niches in a modern, industrialized society. Dogs accompanied their owners into new leisure spaces like the beaches and boardwalks of resort towns. In 1909, for instance, the Philadelphia Inquirer observed the growing numbers of dogs in Atlantic City that had a “playful habit of rushing pell-mell into the water.” Canines also served as mascots to fighting units in wars including one named Philly, a stray mutt that travelled to Europe with Philadelphia soldiers serving in World War I. They also became associated with advertising and mass entertainment as consumer culture made celebrities of dogs like Nipper, the trademarked fox terrier of RCA Victor in Camden, New Jersey, as well as Rin Tin Tin, and Lassie.

Ascent of Guide Dogs

In the twentieth century, dogs assumed two other important duties as they worked with law enforcement and assisted the visually impaired. Prominent Philadelphia native Dorothy Harrison Eustis (1886-1946) played a significant role in training dogs in both tasks. Following World War I, Eustis relocated to the Swiss Alps where she trained German Shepherds as police dogs. However, in 1927, after she published an article in the Saturday Evening Post on a school in Germany that taught dogs to guide blind veterans, readers inundated Eustis with mail asking how they might acquire such useful companions. This intense interest persuaded Eustis to found the Seeing Eye, the nation’s first trainer of guide dogs, in 1929. Within three years, the institute had established its headquarters in Whippany, New Jersey, and it moved to Morristown in 1966. By 2014, the Seeing Eye had placed more than sixteen thousand guide dogs across the United States.

The reliance on canines’ acute senses and sociability accelerated their use as service animals in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century. Canine Partners for Life, founded in 1989 in Cochranville, Pennsylvania, pioneered the use of dogs in alerting their human partners to a variety of medical conditions including diabetes, seizures, and cardiac arrest. In addition, dogs assumed therapeutic roles for some individuals, relieving anxiety and helping their owners to cope with the stresses of everyday life. Yet these new uses for dogs blurred the line between pet and worker as when Canine Partners for Life had to sue to recover one of its service dogs from a deceased owner’s family in 2016.

With an estimated 350,000 dogs in the city in 2015, Philadelphians have continued the longstanding trend of keeping dogs for companionship and pleasure rather than for their practical utility. The shared emotional bond has encouraged humans to see dogs as friends and family, and consequently owners have insisted upon amenities and access for their pets unheard of in the past. Within the city and its surrounding region dog parks have sprouted up where canines can frolic and socialize off leash. In New Jersey, resort towns such as Wildwood have reserved stretches of beaches for dogs and their owners to enjoy the ocean.

At the same time dogs have come to occupy a cherished place in the home, they have also become emblematic of the rampant consumerism of the twenty-first century. In 2016 alone, Americans spent more than $66 billion dollars on their pets. New businesses such as bakeries, dog-walking services, and pet-friendly vacation planners have catered to the inseparable bonds between some humans and their canine companions. With its origins dating back to 1879, the popularity of the Kennel Club of Philadelphia’s dog show attained new heights as its television broadcast became a Thanksgiving tradition in 2002, annually showcasing some of the most fashionable breeds for viewers. More troubling, though, has been the proliferation of puppy mills breeding dogs in crowded and unsanitary conditions to fulfill intense demand. State legislation, including New Jersey’s Pet Purchase Protection Act enacted in 2015, has cracked down on problematic breeders, requiring pet stores to deal only with reputable operations and disclose breeder information to consumers.

The relationship between dogs and people has evolved over millennia. While many of the former roles that dogs assumed in human lives have long since become obsolete, new ones have emerged to illustrate the connection between the species remains alive and well.

Jonathan Hall is an environmental historian, specializing in the history of animals in the nineteenth century. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Montana. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Dog Days of Philadelphia (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Incident On Wissahickon White Trail, Or, An Open Letter To Dog People (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Pennsylvania Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (University of Pennsylvania Libraries)

- Dog Regulations and Best Practices (City of Philadelphia)