Pharmaceutical Industry

Essay

Philadelphia played a key role in the birth of the American pharmaceutical industry in the early nineteenth century, and the region remained a major pharmaceutical center into the early twenty-first century. Home since the colonial period to many of America’s leading scientific, educational, and medical institutions, Philadelphia was well-positioned to support the emergence of a pharmaceutical industry. The nation’s first drug mill was established in Philadelphia in the 1810s, and the city hosted a significant concentration of drug makers over the years, as well as related industries such as chemical manufacturing and supporting institutions such as research universities and hospitals.

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, doctors and pharmacists generally made their own medicines, grinding and mixing materials into powders and extracts themselves. Most medicines were imported from England, however, until the War of 1812 interrupted the supply and spurred domestic drug manufacturing. It was at this point that the American pharmaceutical industry began in earnest. Several Philadelphia pharmacists and chemists branched into small-scale drug manufacturing, and some of these evolved into wholesalers or larger manufacturers.

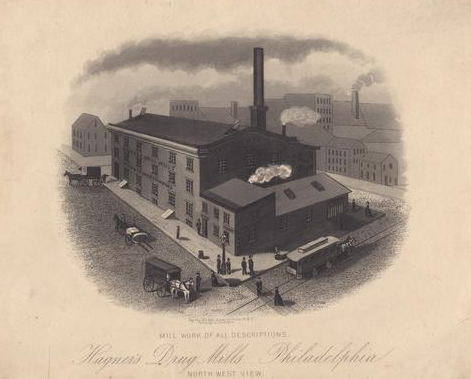

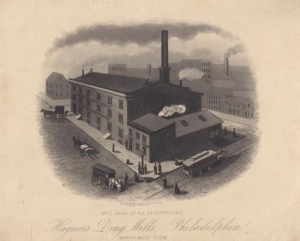

Philadelphia’s first large-scale drug manufacturer was not a pharmacist or chemist, but mill owner Charles Hagner, who in 1812 used his water-powered mill in East Falls to grind several tons of cream of tartar into powder for a local druggist. Hagner’s milling process accomplished in one day what would have taken months by the traditional mortar and pestle method, a feat that generated great interest in the nation’s emerging drug industry. Hagner thereafter focused on grinding materials for medicines, establishing America’s first drug mill at his East Falls location. In 1820 he moved his business to Manayunk, and in 1839 he built a large steam-powered plant in Northern Liberties.

Dozens of Manufacturers Arise

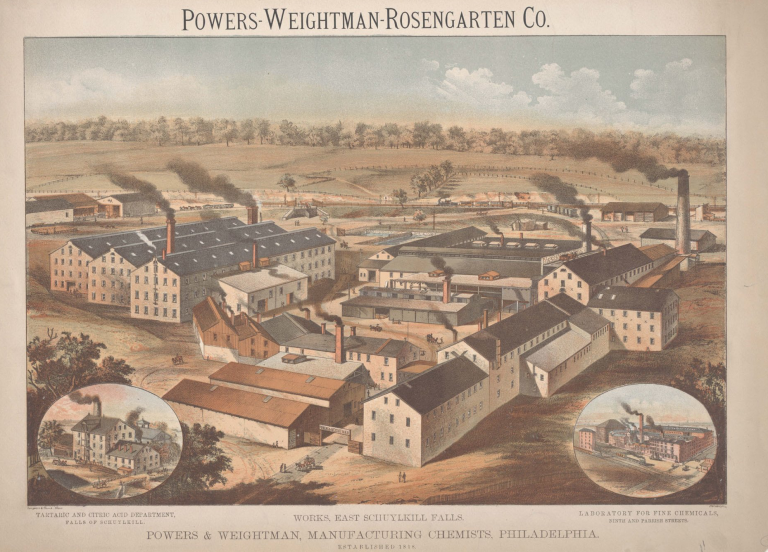

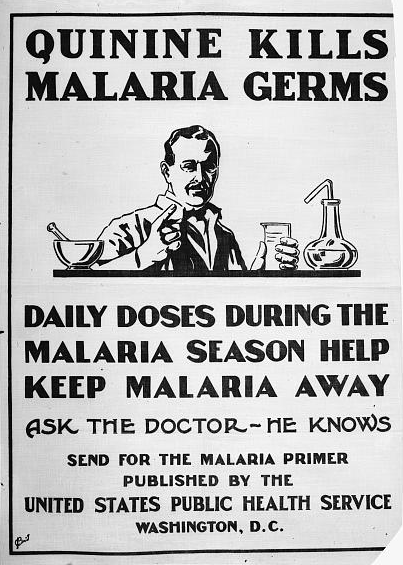

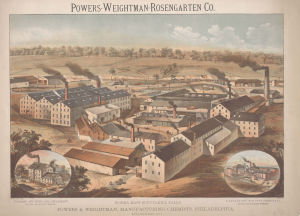

The antebellum period saw the establishment of dozens of pharmaceutical and chemical manufacturers in Philadelphia, fostered by the city’s strong medical, scientific, and educational communities. Powers & Weightman, founded in 1818 by English immigrants, and Rosengarten & Sons, founded in 1822 by a German immigrant, became two of the world’s largest manufacturers of quinine in the nineteenth century. Advertising themselves as “manufacturing chemists,” the two companies made a wide variety of chemicals and medicines before merging in the early twentieth century. John Smith & Company, founded in 1830 by John Smith (d. 1845), and John Wyeth & Brother, founded in 1860 by brothers John (1834–1907) and Frank Wyeth (1836–1913), were two other drug companies established by pharmacists in antebellum Philadelphia. Both began as small-scale operations and grew into pharmaceutical giants. Following various mergers and acquisitions over the years, both remained active in the Philadelphia area in the early twenty-first century.

Robert Shoemaker (1817–96) was yet another early nineteenth-century Philadelphia pharmacist turned drug maker. Shoemaker took over a local pharmacy in 1837 and shortly thereafter began developing glycerin. In 1846 he became the nation’s first commercial manufacturer of the drug. In 1856 William Warner opened a drug store in Philadelphia, where he developed a process for coating medicine tablets with sugar to improve their taste. Warner later gave up his retail business to focus on manufacturing medicines. His company eventually became Warner-Lambert, a major national pharmaceutical firm.

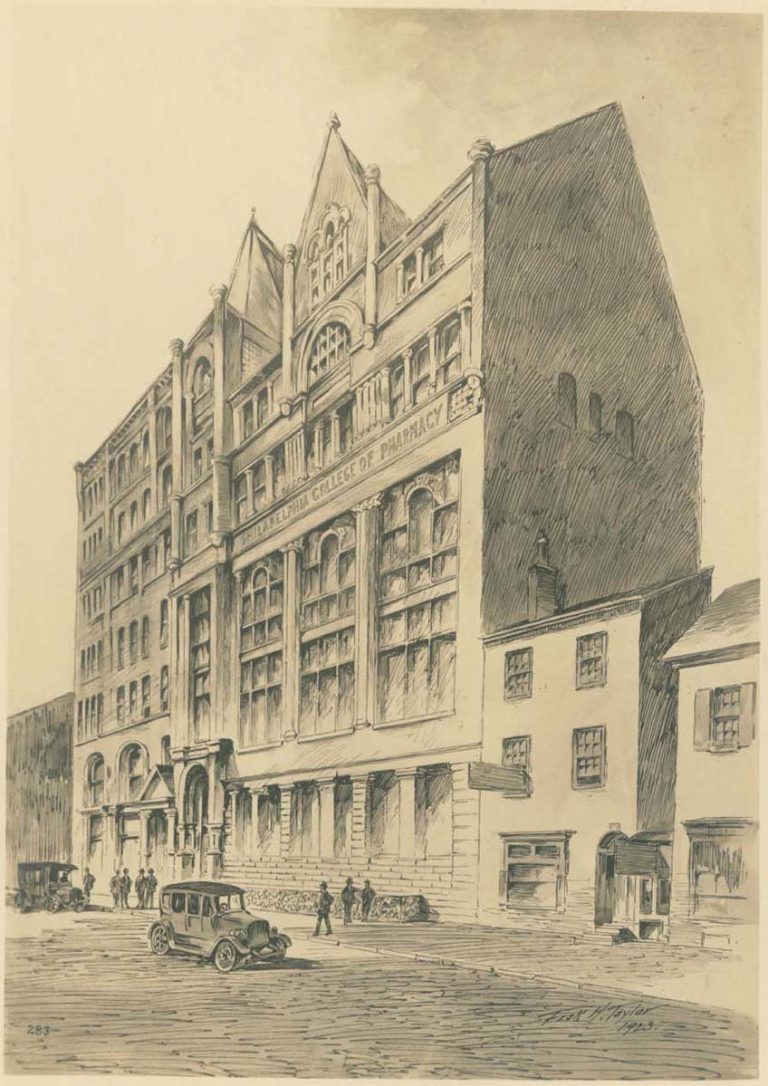

Philadelphia’s status as America’s preeminent early drug manufacturing center was further enhanced by the founding in 1821 of the nation’s first pharmacy college, the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy (PCP), later renamed the University of the Sciences. In addition to training pharmacists, the college’s mission was to “invite a spirit of pharmaceutical investigation and research.” Many of the nation’s leading pharmaceutical executives of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries graduated from PCP.

Philadelphia dominated the American pharmaceutical industry throughout the antebellum period. Forty Philadelphia firms accounted for approximately 30 percent of the total value of the medicines, drugs, and extracts produced in the United States in 1860. Many of these companies benefited significantly from supplying medicines for the Civil War effort and saw considerable growth in the postwar period. In 1872 Wyeth employee Henry Bower (1833–96) developed a rotary tablet machine that allowed for mass production of medicines with precise dosages. The machine greatly expanded Wyeth’s manufacturing capacity and won awards at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia.

Growth of McNeil and Mulford

Local pharmacists continued to branch into drug manufacturing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In 1879 Robert McNeil (1856–1933), a PCP graduate, became proprietor of a drug store in Kensington, from which his son established McNeil Laboratories. The company grew to be one of the region’s major drug makers. Pharmacist Henry Kendall Mulford (1866–1937), also a PCP grad, founded the H. K. Mulford Company in the 1880s from his drug store in downtown Philadelphia. Mulford later focused on making vaccines and in 1895 offered the first commercially available diphtheria antitoxin produced in America. The company built a large plant in Glenolden, Delaware County, which produced several types of vaccines.

Young chemist Albert Barnes (1872–1951) took a job at H. K. Mulford in 1898, but left the following year to form a partnership with another chemist to make a new antiseptic they developed. After the partnership dissolved in 1908, Barnes created the A. C. Barnes Company to manufacture the product. The company was very successful, and Barnes used the wealth he amassed to collect art and establish the world-renowned Barnes Collection.

Philadelphia was also a major center for the production of “patent medicines,” commercially available over-the-counter nostrums that were sold under brand names. Although their effectiveness was often dubious, patent medicines were marketed with colorful, exaggerated claims of their therapeutic qualities and were very popular in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Thomas Dyott (1771–1861), America’s first successful patent medicine manufacturer, made and sold a variety of elixirs and ointments in Philadelphia in the early nineteenth-century. In the 1810s he built a substantial glass works in Kensington to make bottles for his products. At the turn of the twentieth century, Philadelphia was home to two major patent medicine manufacturers, Dr. D. Jayne & Sons and Johnston, Holloway, & Company.

By 1909, there were 174 drug makers in Philadelphia, along with numerous chemical companies and several major research universities and hospitals. The concentration of these industries and institutions made the region a key center for pharmaceutical research and development throughout the twentieth century. In the early 1940s, West Chester, Pennsylvania, chemist G. Raymond Rettew (1903–73) developed a method for mass producing penicillin, based on his work with mushrooms (mushroom growing was a major industry in Chester County). Sponsored by Wyeth (then operating as American Home Products), Rettew’s Chester County Mushroom Laboratories in West Chester became the world’s leading producer of penicillin, which was put to immediate, extensive use during World War II.

Pharmacy College Influence Persists

Graduates of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy continued to play leading roles in the local pharmaceutical industry, particularly in family-run companies. At McNeil Laboratories, Robert McNeil, Jr. (1915–2010), grandson of the company founder, joined the firm after graduating from PCP in 1938. In the 1950s he oversaw development of the pain reliever Tylenol, a very successful medicine that became the company’s signature product. Similarly, at William H. Rorer, Inc., founded in 1910, Gerald F. Rorer (1908–76), son of the founder and a 1931 PCP graduate, took over the family-run drug company, based in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, and transformed it into a major pharmaceutical firm, largely on the strength of its popular antacid, Maalox.

Mergers and acquisitions, common in the pharmaceutical industry from its earliest years, continued over the course of the twentieth century. Powers-Weightman-Rosengarten, formed through the merger of two Philadelphia pharmaceutical giants in 1905, consolidated with Merck & Company in 1927 and moved to northern New Jersey. H. K. Mulford merged with Sharp & Dohme in 1929, which in 1953 was also acquired by Merck & Company. John Smith & Company became Smith, Kline, & French in 1929, and in 2001 merged with English drug maker Glaxo to form GlaxoSmithKline. French multinational firm Rhone-Poulenc acquired Rorer in 1990. Wyeth was acquired in 1932 by American Home Products, parent company to a number of pharmaceutical, home care, and food product manufacturers. American Home Products later divested itself of its non-pharmaceutical companies to focus specifically on drug making and in 2002 adopted the Wyeth name for the entire company. In 2009 Wyeth was acquired by Pfizer, a multinational pharmaceutical company with headquarters in New York City. Nine years earlier, Pfizer had acquired Warner-Lambert.

Increased consolidation among drug makers in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries gave rise to “Big Pharma,” a select group of very large multinational pharmaceutical firms that dominated the industry. The Philadelphia area was home to several of these pharmaceutical giants. Some had originally been founded in the city and remained in the region; others moved to the area later in their development. Of the former, the only company still located within the city itself was GlaxoSmithKline, which in 2013 moved one of its two North American headquarters from Center City to the Navy Yard in South Philadelphia. Both Wyeth and McNeil remained in the area but moved to the suburbs, McNeil to Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, in 1961 after being acquired by Johnson & Johnson in 1959, and Wyeth to various suburban locations before consolidating in Collegeville, Pennsylvania, in 2003.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, Philadelphia stood at the center of a mid-Atlantic pharmaceutical corridor stretching from Delaware to northern New Jersey that included many of the world’s Big Pharma companies. In addition to GlaxoSmithKline, Wyeth, and McNeil, the Philadelphia region was home to Endo Pharmaceuticals in Malvern, Pennsylvania, originally established in 1920, later acquired by DuPont, and spun off as a separate company in 1997; AstraZeneca in Wilmington, Delaware, established in 1999 through a merger of two large English and Swedish pharmaceutical companies; and Teva, an Israeli generic drug maker that established a North American headquarters in Montgomeryville, Pennsylvania, in the early 2000s. Numerous other pharmaceutical companies, large and small, were based in the broader Philadelphia metropolitan area in the early twenty-first century as well. They ranged from traditional drug makers to biotechnology firms to research and development companies, all part of the expansive “Life Sciences” sector that comprised a major part of the regional economy. A 2016 report commissioned by a consortium of local business and industry organizations noted that the sector encompassed 1,200 life sciences companies across the region, employed 48,900 workers, and was responsible for $24.6 billion in output.

From its key role in the creation of the American pharmaceutical industry in the early nineteenth century to its position as home to a number of major drug companies in the early twenty-first, the greater Philadelphia region was an important pharmaceutical center for over two hundred years.

Jack McCarthy is an archivist and historian who specializes in three areas of Philadelphia history: music, business and industry, and Northeast Philadelphia. He regularly writes, lectures, and gives tours on these subjects. His book In the Cradle of Industry and Liberty: A History of Manufacturing in Philadelphia was published in 2016 and he curated the 2017–18 exhibit Risk & Reward: Entrepreneurship and the Making of Philadelphia for the Abraham Lincoln Foundation of the Union League of Philadelphia. He serves as consulting archivist for the Philadelphia Orchestra and Mann Music Center and from 2011–16 directed a major archival project for the Historical Society of Pennsylvania focusing on the collections of the region’s many small historical repositories.

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Greater Philadelphia Region Life Sciences Report (PDF, CEO Council for Growth)

- G. Raymond Rettew Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Philadelphia College of Pharmacy (University of the Sciences)

- Quinine - Top Pharmaceuticals (American Chemical Society)

- Sketch of the Interior of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- The Barnes Foundation