Mayors (Philadelphia)

By Andrew Heath

Essay

The Philadelphia mayoralty, almost as old as the city itself, has changed markedly since its inception. When the post was created in the eighteenth century, citizens put up their own money in order to avoid having to serve. By the early 2000s, in contrast, candidates and supportive political action committees poured millions into mayoral elections. Tracing the office’s transformation offers insights into the social makeup of municipal politics, battles between party regulars and reformers, and long fights over the rightful place of executive authority in city government.

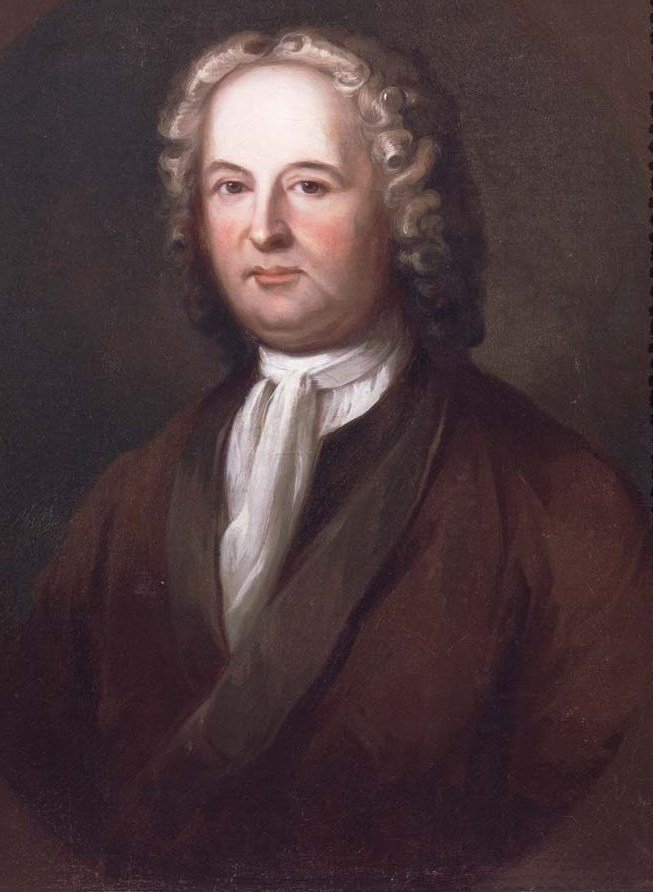

William Penn’s city charter of 1701 granted a measure of self-government to Philadelphia but left little room for energetic activity on the part of the mayor. Mayors served one-year terms and were elected by aldermen, who held their positions for life. The position was not particularly appealing. Although some of the province’s leading men–among them Penn’s colonial secretary James Logan (1674-1751; in office 1722-23)–occupied the mayor’s seat, finding willing volunteers sometimes proved so difficult that the corporation resorted to fining aldermen who refused to serve. In 1747, Anthony Morris even fled the city to avoid the job, and the fines levied on refuseniks boosted the city treasury. Such reluctance to take up the post is understandable. Until the mid-eighteenth century, the mayoralty was unsalaried, yet often involved great personal expense in terms of time and money. The mayor accrued some appointive, regulatory, and judicial powers, but was really first among equals with the aldermen. When the colonial city charter came to an end in 1776 and Philadelphia came under the authority of the state government, the position ceased to exist. Its passing does not seem to have been lamented.

The new city charter of 1789 opened elements of city government to citizens’ control and re-created the role of mayor. Unlike its near contemporary, the federal Constitution, the charter did not establish a clear separation of powers, as the mayor (elected indirectly from the aldermen) retained a seat in Council. In 1796, however, legislators established a clearer division between the branches of municipal government, with the popularly elected councils choosing a mayor from a Board of Aldermen appointed by the governor. The mayor’s appointive powers grew and he retained his judicial role. But councils undermined his executive authority by creating committees to run city services like water and gas.

Lawyers and Merchants

Philadelphia’s mayors in the Early Republic tended to be drawn from the upper ranks of society. Lawyers and merchants were the most frequent occupants of the post, and if few came from the city’s so-called “first families,” they were occasionally of high rank. One example is George Mifflin Dallas (1792-1864; in office 1828-9), who was the son of a secretary of the treasury, and later became vice president of the United States. But Dallas’s subsequent political success marks an exception among mayors of the period. While many citizens who held the office had served on city councils or on one of the municipal trusts, few were career politicians. The relatively weak powers of the mayor provided little of the patronage needed to cultivate political alliances.

Mayors nevertheless played their part in the party conflict of the era. Federalists and American Republicans vied for mayorships in the Early National era; by the mid-1830s Democrats and Whigs fought over the position. Like many offices in Jacksonian America, the mayoralty was opened to direct election, but the 1839 reform did not change the social background of incumbents, who continued to hail from the upper ranks of society. Take for example Richard Vaux (1816-95; in office 1856-8), the son of an eminent Quaker philanthropist, and a man who danced with Queen Victoria at her coronation. But if mayors rarely sprang from the “common men” themselves, they often played their part in the era’s popular politics. John Swift (1790-1873; in office 1832-38, 1839-41, 1845-49), a Whig whose twelve terms straddled the introduction of direct elections, led a mob that dumped abolitionist literature in the Delaware in 1835. Even as late as the Civil War, Mayor Alexander Henry (1823-83; in office 1858-66) appeared in person to calm the crowd.

The Consolidation Act of 1854, which made the boundaries of city and county contiguous, extended the territorial reach of the mayor’s powers but added little to the office’s executive responsibilities. Consolidation swallowed up the independent boroughs and districts that had their own municipal arrangements. Northern Liberties was unusual in having a mayor; most, like Kensington, elected a president from a board of commissioners. Advocates of the new charter had imagined the measure, by annexing fast-growing suburbs, would give Philadelphia’s mayor the stature of a state governor. Yet beyond granting a veto over legislation and extending the term of office to two years, it did little to augment the mayor’s power. To the frustration of several incumbents of the office, the post-consolidation councils reasserted executive control over city departments and left only the police force under the mayor’s direct command.

The Police Force as Political Tool

That police force, however, proved a considerable weapon in the hands of wily mayors. A handful of day constables and night watch had come under the mayor’s control in the Early Republic, but an epidemic of rioting in the 1830s and 1840s spurred the creation of a metropolitan-wide police force in 1850, which by 1854 amounted to several hundred officers. Here was a patronage pot—and a source of election-day muscle—that mayors could exploit. Robert T. Conrad (1810-58; in office 1854-56), the first post-consolidation mayor, appointed his nativist backers to the police, while his successor, the wealthy Democrat Vaux, rewarded his Irish-American supporters likewise. Vaux, who enjoyed joining the force on nightly patrols, set the standard for an activist mayor committed to enforcing the law. But mayors could be selective about the laws they chose to enforce. In 1870, for example, federal troops needed to be called in to protect Black voting rights under the newly ratified Fifteenth Amendment when it became clear the Democratic mayor Daniel M. Fox (1809-90; in office 1869-72) was likely to use his police to block African Americans’ access to the polls.

Aside from the police force, though, the power of post-1854 mayors tended to come less from their stipulated responsibilities under the city charter, and more from Harrisburg-created commissions. The postwar mayor William S. Stokely (1823-1902; in office 1872-81), for instance, used his position as head of the body delegated to erect a new city hall to build a political ring. His ascent indicated that party loyalty now mattered more than social respectability in the race for office. Genteel members of the Republican Union League turned down Stokely—a journeyman confectioner in his youth—for membership.

Stokely’s rise signaled the beginning of eight decades of Republican domination of city hall. Prior to consolidation, the two-square-mile city proper tended to return Whig mayors, while the outlying districts leaned Democratic. Early elections after 1854 proved competitive, but the Civil War and the growing importance of manufacturing to the metropolitan economy meant that by the mid-1870s voters tended to prefer a pro-tariff Republican in the mayor’s seat. The mayor, however, found it hard to translate the prestige of the office into a metropolitan-wide political organization. Executive control in the city was too fragmented, with councils, county officers, and state Republicans each protecting their own patronage pots. With the exception of a figure like Stokely, who had access to the enormous budget of the Public Buildings Commission, mayors tended to be the front men for Republican bosses rather than masters of the machine themselves.

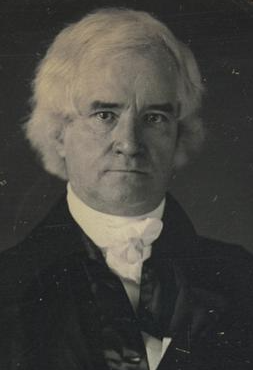

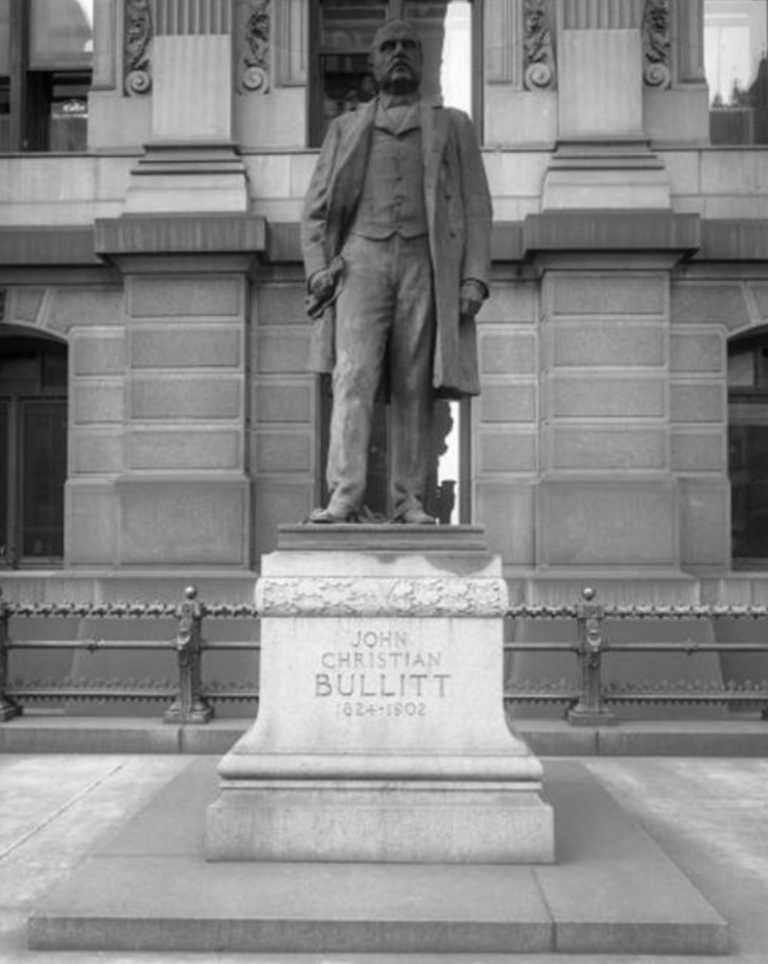

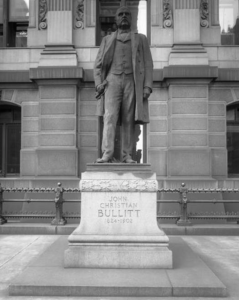

The Bullitt Bill—an 1885 revision to the city charter named after its architect, lawyer John C. Bullitt (1824-1902)—marked an attempt to consolidate executive power in the mayor. It gave the mayor the power to appoint not just a chief of police but also a head of a department of public works. Good government advocates celebrated the reform, which initially appeared to be having the desired effect. The first two officers to wield “chief executive” power after the charter revision were Edwin Fitler (1825-1896; in office 1887-91) and Edwin Stuart (1853-1937; in office 1891-95), men who impressed their contemporaries with honest stewardship. But both had to leave office under the Bullitt Bill after a single four-year term. In a city openly disparaged as “corrupt and contented,” their legacy proved short-lived.

Influence of Reformers

By the early years of the twentieth century Philadelphia politics had settled into a pattern. “Organization” Republican mayors were rarely troubled by a moribund Democratic Party (the leaders of whom were on the Republican payroll), but they did face occasional challenges from bolting reformers, who called for sweeping the Augean stables of city government. Thomas B. Smith (1869-1949; in office 1916-20), who entered politics after making his money in bail bonds and allied with Republican kingmakers the Vare brothers, is representative of the former. He was indicted while in office for his role in the election-day murder of a policemen. Rudolph Blankenberg (1843-1918; in office 1911-1916), a veteran of Gilded Age reform movements, represents the latter; his ardent progressivism sought to supplant patronage with merit as the basis for city appointments, and he expanded city services while cutting costs. But in practice, the stark line between “organization” and reform mayors can be overdrawn. Some, like John Weaver (1861-1928; in office 1903-07) flitted between the two camps for political advantage, and even the ardent reformer Blankenberg had to convince voters that he was a good Republican in principle. No reform party managed to capture the mayoralty for long, and except when the regular Republican Party was divided, reformers tended to be trounced at the polls.

The Republicans’ long dominance of City Hall came to an end after World War II. During the 1930s, the Republican Party had remained ascendant locally even as the New Deal domestic programs of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) swung Philadelphia into the Democratic camp in national elections and Mayor Joseph Hampton Moore (1864-1950; in office 1920-24, 1932-36) blamed the unemployed for their plight during the Great Depression. But under the leadership of two zealous young New Dealers—Joseph Clark (1901-90) and Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974)—the reinvigorated Democrats won control of the mayoralty in 1952. Both Clark and Dilworth served as reforming mayors (the former in office 1952-56; the latter 1956-62), though their more important legacy for Philadelphia may have been the “Home Rule” charter of 1951, which strengthened the mayor’s executive powers, weakened the city councils, and bolstered an independent civil service. Both Clark and Dilworth came from patrician backgrounds, and their tenure hinted at a return to the tradition of upper-class service that had come to an end after the Civil War, but the age of reform they inaugurated did not last. A Democratic machine—based on alliances with organized labor rather than the ward bosses of the old Republican organization—gained control of city hall in the 1960s.

Ethnic politics also began to shape the mayoralty. Dilworth’s successor, the loyal Democrat James Tate (1910-83; in office 1962-72), was the first Irish Catholic to occupy city hall. Tate in turn was succeeded by Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo (1921-91; in office 1972-80), a “big man” Dilworth had initially promoted to court favor with Italian Americans. Rizzo’s popularity among white ethnics extended well beyond South Philadelphia, and amid rising fears of violent crime, he portrayed himself (much like early post-consolidation mayors) as a defender of law and order. To African Americans and white liberals, though, his disregard for civil rights and reputation for sanctioning police brutality made him a hated figure. Rizzo’s attempt to change the Home Rule charter to enable him to run for a third term failed, though he had two more tilts at the office in 1987 and 1991, when he suffered a fatal heart attack at his campaign office.

Since the middle decades of the nineteenth-century white ethnics had helped to determine Philadelphia’s mayoral elections, but in the years that followed Rizzo’s turbulent reign, the path to city hall passed through the African American community, which had grown in political importance due to migration from the South and white flight to the suburbs. With the Republicans now as irrelevant as the Democrats had been in the early twentieth century, Democratic primaries became the real electoral battleground. Wilson Goode (born 1938; in office 1984-92) became the first African American mayor of the city. His administration was marred by the challenge of running a shrinking city with an unsympathetic administration in Washington, and by the catastrophic decision to bomb the West Philadelphia house of the MOVE sect. Divisions among African American political leaders paved the way for the pro-business Democrat Ed Rendell (b. 1944; in office 1992-2000) to succeed Goode, though he was followed by two African Americans, the “organization” Democrat John Street (b. 1943; in office 2000-08), who in contrast to Rendell focused on outlying neighborhoods rather than Center City, and the reformist Michael Nutter (b. 1957; in office 2008-2016). In 2016, the Irish American councilman Jim Kenney (b. 1958) took over from Nutter, and in 2023 voters elected Cherelle Parker (b. 1972) as the first Black woman to become mayor. These twenty-first-century incumbents played a part in a “strong mayor” system that bore little resemblance to the mayoralty of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Andrew Heath is a Lecturer in American History at the University of Sheffield, United Kingdom, and is the author of In Union There Is Strength: Philadelphia in the Age of Urban Consolidation (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Rizzo statue to move in 2 to 3 years, Kenney says (WHYY, August 10, 2018)

- Kenney outlines priorities, vows to work right through the end of his term (WHYY, January 11, 2023)

- Cherelle Parker makes history: Philly elects first Black woman mayor (WHYY, November 7, 2023)

- Mayor Cherelle Parker sworn in, delcares public safety emergency (WHYY, January 2, 2024)

Links

- List of Mayors of Philadelphia (City of Philadelphia Department of Records)

- A City Charter in a Box (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Bullitt Bill - Full Text (HathiTrust)

- Frank Rizzo Mural (Explore PA History)

- Mayors' Correspondence and Files (City of Philadelphia Department of Records)

- Philadelphia City Charter, 1701 (PDF) (Phila.gov)

- The Censor Mayor (PhillyHistory Blog)

- The City Government of Philadelphia - Full Text (1887) (HathiTrust)