Aeronautics and Aerospace Industry

Essay

From the aeronauts of the early republic to the jets, missiles, and rockets of the Cold War era, the growth and development of the aeronautical and aerospace industry in the Philadelphia region has exemplified a gradual shift from amateur pursuits to a more formalized industry and infrastructure. Across several centuries, the city and surrounding suburbs emerged as a hub of experimentation and innovation driven by the interests of prominent Philadelphians, by a favorable geographic locale, and by increasing interaction between industry and government, particularly in the latter half of the twentieth century.

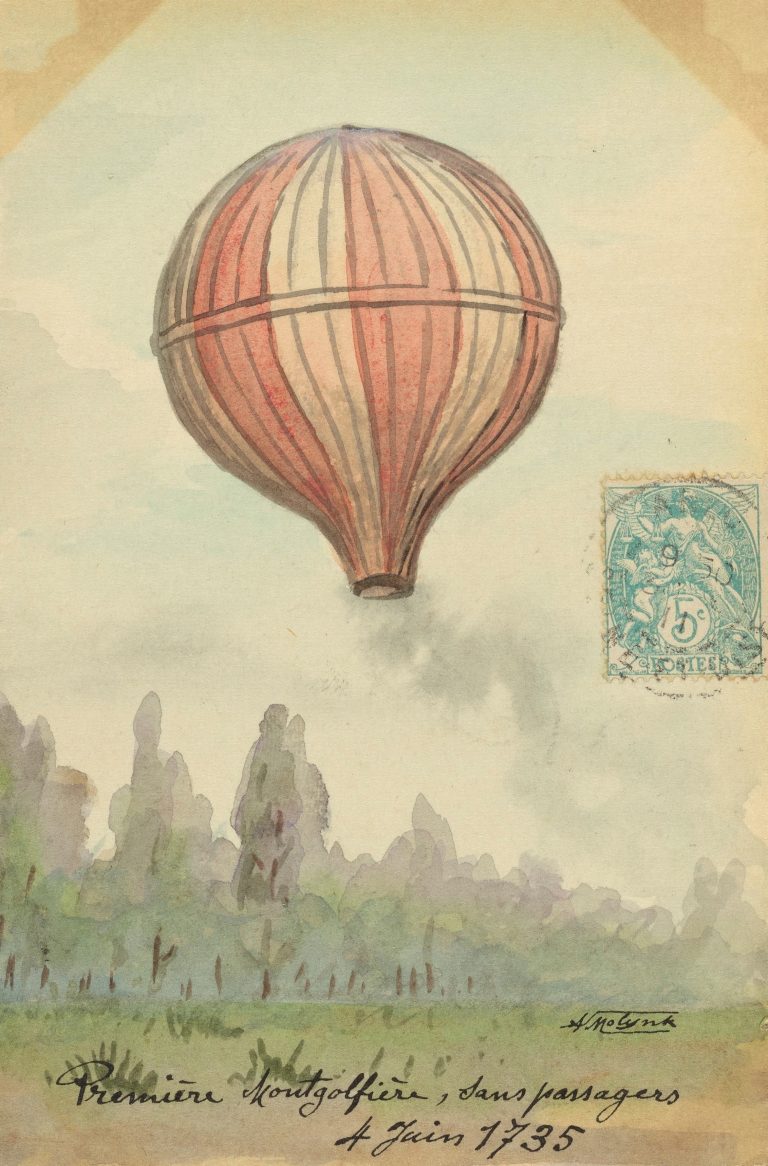

Beginning in the eighteenth century, early explorations in flight primarily followed two distinct avenues: hot-air balloons developed by brothers Joseph-Michel (1740-1810) and Jacques-Étienne (1745-99) Montgolfier in Paris and hydrogen-inflated balloons tested by the Montgolfiers’ contemporary and fellow Frenchman Jacques Alexander Caesar Charles (1746-1823). Serving as ambassador to France from 1778 to 1785, Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) witnessed and reported on such experiments to associates and friends in Philadelphia, stoking American interest in aeronautical flight.

As Philadelphia, then serving as the national capital, emerged as a focal point for ballooning in the new republic, early aeronautical endeavors in the city had mixed success. On May 10, 1784, Dr. John Foulke (1757-96) successfully recorded the first balloon flight in America, a small, unmanned paper test balloon released from the courtyard of the Dutch minister’s residence. Following Foulke’s demonstration, Maryland innkeeper and lawyer Peter Carnes’ (1749-94) ascension in a tethered hot-air balloon at the city prison yard on July 17, 1784, failed spectacularly when a gust of wind knocked Carnes from the balloon before it caught fire and fell to earth. A decade later, the exploits of European balloonist Jean-Pierre Blanchard (1753-1809) renewed Philadelphians’ interest in aeronautics; on January 9, 1793, citizens paid $2 to $5 per ticket to witness Blanchard’s ascent from the Walnut Street Prison yard at Sixth and Walnut Streets, a spectacle sponsored and attended by President George Washington (1732-99).

Ballooning Set the Stage

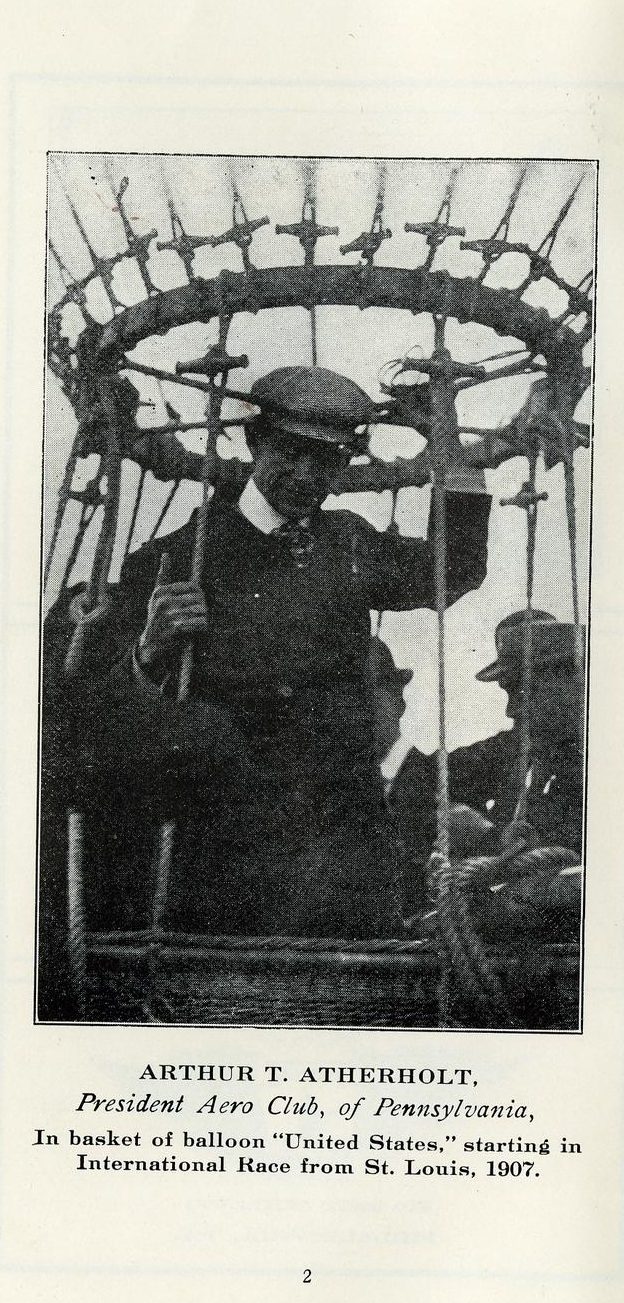

While public enthusiasm for ballooning waxed and waned throughout the nineteenth century, early aeronautics nonetheless fostered a public receptiveness to flying that increased as inventors turned their attentions to the problem of heavier-than-air flight. At the dawn of the twentieth century, interest in fixed-wing aircraft and other flying machines drew together a mix of scientists, engineers, part-time researchers, and enthusiasts to form a growing aeronautical community in the Philadelphia region. Notable among these individuals was George A. Spratt (1870-1934), a medical student from Coatesville, Chester County, Pennsylvania, who channeled his scientific training into the study of aerodynamics and participated in the Wright brothers’ gliding experiments at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in the summer of 1901. Following the Wright brothers’ success in 1903, airplanes, like balloons a century earlier, gripped the public imagination and developed initially as a form of entertainment. Between 1908 and 1915, the Point Breeze racetrack and the Philadelphia Naval Yard at League Island became popular destinations for exhibition flights and air meets sponsored by the Aero Club of Pennsylvania, which formed in December 1909 from the merger of the Aero Club of Philadelphia and the Philadelphia Aviation Society. In addition to exhibition flights, races between airplanes were also a popular attraction; locally, department store chain Gimbel Bros. (Gimbels) sponsored a 1911 contest from New York to Philadelphia that concluded at Belmont Plateau in Fairmount Park.

While the Aero Club of Pennsylvania, as well as aero clubs at local colleges and universities including the University of Pennsylvania, Haverford, and Swarthmore, brought a degree of organization to amateur aviation, American involvement in World War I served as a catalyst for the emergence of a true aeronautical industry in Philadelphia and the nation. As the War Department increasingly recognized the airplane’s potential for scouting, observation, and tactical support of ground troops, ambitious goals of producing 22,625 airplanes and 4,500 aircraft engines led to the construction of government-owned and operated facilities like the Naval Air Station Lakehurst (New Jersey) and the Naval Aircraft Factory at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Established in 1917, the Naval Aircraft Factory quickly became a critical hub for the manufacture of flying boats, seaplanes, motors, and other accessories; by war’s end, the facility boasted over one million square feet of floor space and employed more than 3,600 workers. The region’s contributions to the war effort also included the manufacture of component parts by Philadelphia-based firms like G.E.M. Manufacturing, which specialized in aerial cameras, and the J.G. Brill Company, which produced rough cylinder motor liners at its trolley and rail car plant at Sixty-Second Street and Woodland Avenue, as well as the training of aviators and support personnel at the Essington Aviation Station located on the former site of the Lazaretto quarantine station.

Military Influence Persists

Following the war, the symbiotic relationship between government and the nascent aviation industry remained critical, as military needs continued to influence industrial production and priorities, particularly in Philadelphia. Most significantly, the Naval Aircraft Factory scaled back its workforce to approximately twelve hundred workers and, throughout the 1920s, shifted focus from the production of aircraft to research and development of experimental designs. Initially, private industry followed suit and increasingly focused on the engineering and testing of materials and component parts until federal legislation expanding airmail service contracts for private carriers spurred demand for new and more efficient aircraft. Among others, aviation enthusiast Harold F. Pitcairn (1897-1960) capitalized on the 1925 Kelly Air Mail Act to establish a manufacturing facility for light utility aircraft at his Bryn Athyn airfield under the auspices of Pitcairn Aviation, the passenger service and flying school based in Willow Grove. Renewed demand for military and civil aircraft similarly spurred companies like the Huff-Daland Aero Corporation of Ogdensburg, New York, to establish a new headquarters and production plant along the Delaware River in Bristol, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Notably, the arrival of Huff-Daland in 1926 coincided with the opening of Philadelphia’s first municipal airport, a 111-acre facility located in the Eastwick section of the city, while public interest in the 1927 transatlantic flight by Charles Lindbergh (1902-74) and his subsequent tour, which included stops in Philadelphia and Wilmington, Delaware, likewise spurred a boom in commercial airport construction, including the William Penn Airport on Roosevelt Boulevard and the Philadelphia Aircraft Company’s airfield on Easton Pike near Doylestown.

Throughout the early decades of the twentieth century, Philadelphia’s strategic location along primary east-west and north-south arteries significantly spurred the development and growth of aeronautical infrastructure and industry in the city and surrounding region. Nonetheless, aircraft manufacturing and airfield construction contracted sharply during the Great Depression, as companies once again redirected their focus from aircraft manufacturing to component parts. Amidst this shift, the Edward G. Budd Manufacturing Company of Philadelphia distinguished itself for its innovative use of stainless-steel and a pioneering shot-welding fabrication process used to produce aircraft materials that were stronger and more resistant to corrosion. Similarly, the production of engines, rotary wings, and propellers by companies like Fleetwings Inc. of Bristol and Jacobs Aircraft Engine Company of Pottstown helped to sustain the local aviation industry until demand for new aircraft rebounded in the lead-up to World War II. As the nation mobilized for war, the Naval Aircraft Factory once again stepped up production to meet rising demand and expanded into a wealth of experimental, highly classified projects on pilotless aircraft and guided weapons systems that underscored an ever-growing emphasis on research and development. This shift solidified further in 1943, when the Naval Aircraft Factory was renamed the Naval Air Material Center and the facility’s primary duties divided into two units: the Naval Aircraft Modification Unit, which focused on the conversion of service aircraft and special weapons work, and the Naval Air Experimental Station, which conducted laboratory and materials testing. Technological research and innovation similarly dominated wartime work at the Philadelphia-based Steam Division of the Westinghouse Electric Corporation, which engineered and produced the first operational American turbojet for the U.S. Navy in March 1943.

Cold War and Beyond

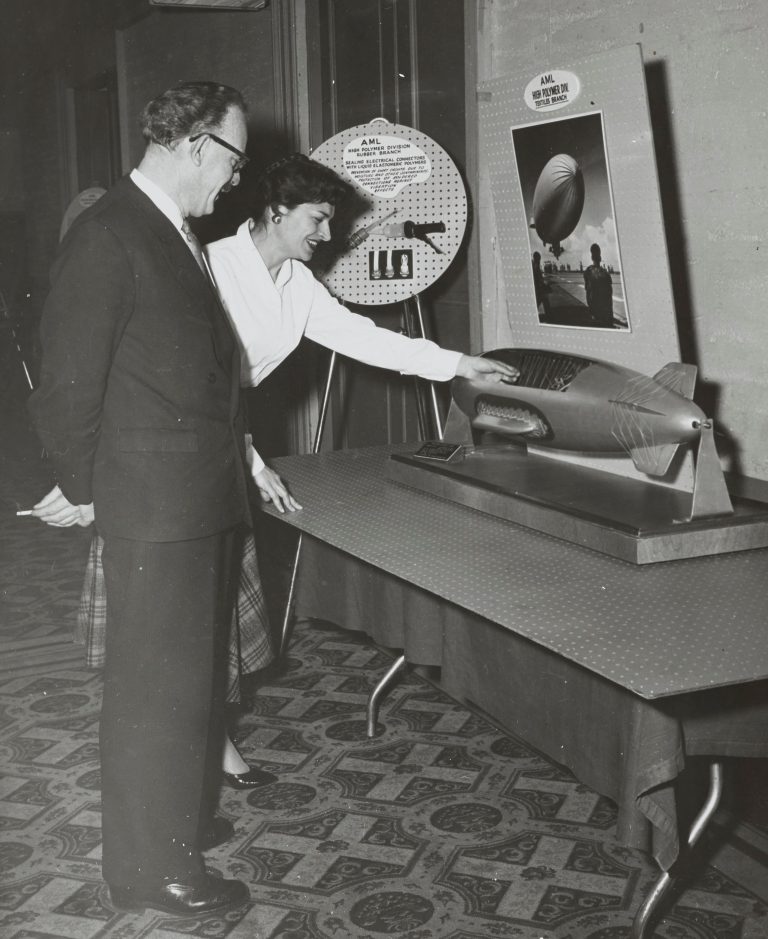

Across the state of Pennsylvania, employment in the aircraft, engines, and parts industries peaked at approximately 45,000 workers in July 1944; from there, employment and production statistics steadily declined into the postwar period, as industries struggled with the effects of demobilization and a market over-saturated with readily available used aircraft. In response, the Naval Air Material Center doubled-down on the research and development of specialty parts and materials, including advanced catapult systems, rocket-powered ejection seats, and improved arresting gear. Similarly, in 1947, the navy’s aircraft plant in Johnsville (Warminster), Bucks County, was converted into the Naval Air Development Station and embarked upon research in aviation electronics, medicine, and unmanned aircraft. Over the next decade, the two facilities evolved further, increasingly focusing on missile and spacecraft technologies and effectively positioning themselves at the forefront of Philadelphia’s burgeoning aerospace industry.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, a number of private corporations across the region joined in these endeavors, including the Boeing Vertol facility in Ridley Park, which specialized in helicopter and rotary wing aircraft; the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) facility in Camden, New Jersey, which developed guided missile and checkout equipment; and General Electric’s Missile and Space Vehicle Department based in Philadelphia, which in 1957 received the company’s first Air Force contract to develop a reentry vehicle for intermediate-range ballistic missiles. In April 1960, General Electric broke ground on a new Space Technology Center in Valley Forge, which became the hub for the company’s Space Division and its work on a range of missile and satellite projects for the remainder of the 1960s and into the 1970s. Despite the growth of private industry in the postwar period, the aerospace industry in Philadelphia arguably reached its apex in Johnsville, which in 1959 became headquarters of the Naval Air Research and Development Activities Command. In this capacity, the facility oversaw the Naval Air Engineering Center’s work on pressure suits used by Project Mercury astronauts, as well as jet and rocket engine research and centrifuge testing to measure the effects of G-force on humans. Several Gemini and Apollo program personnel and astronauts, including John Glenn (1921-2016) and Neil Armstrong (1930-2012), trained at the facility, as well as a number of X-15 space plane pilots.

True to the aerospace industry’s increasing dependence on government contracts and projects, cuts in military spending and the consolidation of facilities toward the end of the Cold War hastened the industry’s decline in the Philadelphia region in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1986, General Electric acquired the RCA Corporation and subsequently sold its entire aerospace division, including the Camden facility, to the Maryland-based Martin Marietta Corporation (later renamed Lockheed Martin) in April 1993. Similarly, the Naval Air Research and Development Activities Command in Johnsville closed in 1996 and many of its buildings were subsequently demolished in 2001, a symbolic end to the long history of the aeronautical and aerospace industry in the Philadelphia region.

Hillary S. Kativa is the Chief Curator of Audiovisual and Digital Collections at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia. In addition to an MLIS from Rutgers University, she holds an M.A. in history from Villanova University and received her B.A. in history and English from Dickinson College. Her research interests include American political history and presidential campaigns, public history, and material culture. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University