Brandywine Valley

Essay

Less than an hour west of the Quaker City lies the Brandywine Valley, for centuries a green and pleasant counterpoint to the dense urbanism that has defined America’s first great metropolis. A region synonymous with gracious living and cultural tourism, the Brandywine Valley has drawn visitors from around the world to enjoy its many public gardens, house museums, and historical attractions. Such tourism has been a longstanding tradition, going back to the nineteenth century, when improved railroad connections made this bucolic area an attractive getaway from crowded Philadelphia, just twenty-three miles away (it was the country’s largest city in 1776 and remained its sixth largest in 2020). In the twenty-first century the fame of the Brandywine Valley continued to grow: a national park, First State National Historical Park, was established there in 2013, preserving 1,100 acres of verdant countryside through which George Washington’s army marched on its way to the Battle of the Brandywine in September 1777, one of the two largest land battles of the American Revolution.

(Library of Congress)

Although a relatively small place geographically, the Brandywine Valley enjoyed an outsized reputation, having often been celebrated by writers and artists, many of them based in Philadelphia (once called “The Athens of America”), who spread its fame widely. Brandywine Creek is only about sixty miles long, less than half the length of Philadelphia’s Schuylkill River, and its watershed of 330 square miles is dwarfed by the Schuylkill’s 1,700 miles. 85 percent of the Brandywine watershed is confined to a single county in Pennsylvania, Chester County. Flowing south, it briefly skirts Delaware County at historic Chadds Ford before reaching its terminus in New Castle County, Delaware.

Only in its last few yards does the Brandywine reach the coastal plain; otherwise, it is the quintessential piedmont stream, rapidly falling over boulders of Wissahickon schist or Brandywine blue rock, at times twisting through rolling agricultural landscapes but then slipping into steep-sided valleys thickly wooded with some of the largest hardwood trees in the northeastern United States. Ecologically, the valley abounds with flora and fauna. This owes to a surprising variety of habitats from freshwater marshes to old-growth forests, and to the region’s felicitous location at the junction of North and South (surveyors Mason and Dixon wintered on the Brandywine during the years they surveyed their famous regional borderline, 1763-67). For example, northeastern plants such as hemlock trees mingle here with southeastern species such as umbrella magnolia.

The Swedes Arrive

Before European settlement, abundant ecological riches made the Brandywine a congenial place for Lenni-Lenape Indians, who hunted game in the hardwood forests or caught shad in the creek, long before dam-building interrupted the migration of fish upriver. The Indians watched in dismay as Swedes arrived in 1638 and built Fort Christina on a gentle rocky outcrop where it could guard the lower reaches of both the Christina River and Brandywine Creek—the first Swedish settlement in the New World. A successful Dutch campaign to seize the fort in 1655 was one of the first military encounters by rival European armies on American soil. The name “Brandywine Creek” is Dutch, of uncertain origin; perhaps it refers to the honey-brown color, similar to brandy, of the stream during one of its frequent floods, in visual contrast to the gray and placid Christina. Other theories abound. Nor is there agreement about whether the Brandywine is a “creek” (the typical usage for centuries) or the more recent “river.”

(Wikimedia Commons)

When William Penn’s Quakers arrived in 1682, Brandywine Creek formed the western boundary of the settled parts of Pennsylvania, with the junction of civilization and wilderness sharply demarcated at “Brumadgam” on the Thomas Holme map of 1687, subsequently Birmingham Township, Chester County. Wilmington, Delaware, was located on a hilltop between the Christina and the Brandywine in 1731, virtually a miniature replica of Philadelphia in layout, and it thrived because of the exceptionally prosperous milling that the Brandywine afforded. With its rapid drop in elevation, this piedmont river was ideally configured for the construction of water-powered mills, as the Swedes had been the first to recognize, establishing a mill-seat in what would become Wilmington’s Brandywine Park, where traces of the ancient dam survived into the twenty-first century.

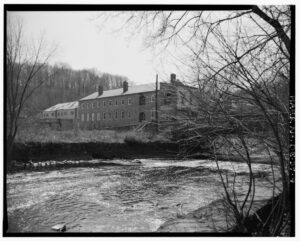

By the late eighteenth century, the Brandywine Valley had become a crucible of the Industrial Revolution in America, with a proliferation of mills (more than 100 on just the Delaware section of the creek by 1793) that used increasingly advanced technology. The main north-south road in early America, linking Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., crossed the Brandywine at Wilmington, where tourists and travelers (among them George Washington) marveled at the fully automated milling technology on display by Market Street Bridge in Brandywine Village, an enclave of expensive Quaker millers’ homes.

Gunpowder and Iron Works

The Brandywine witnessed the American debut of the mechanical production of paper just upstream from Wilmington at Gilpin’s Mill in 1817, triggering a revolution in the production of books, magazines, and newspapers in the young republic. The ability of the fledgling nation to defend itself against menacing European powers was dependent upon the production of gunpowder on the Brandywine by the du Pont family, which arrived in Delaware from France in 1802 in time to supply powder to fight the Barbary pirates at Tripoli (1801-05) and the British in the War of 1812. On the eve of the Civil War, half of the national output of gunpowder came from duPont mills on the Brandywine, including the sturdy stone facilities preserved at Hagley Museum & Library. If industry faded long ago from the Brandywine in Delaware, it continued to thrive upstream at Coatesville, Pennsylvania, where the successor firm to Brandywine Iron Works (1810) remains the oldest steel mill in America. In the twenty-first century, countless local families of Italian and Irish descent could trace their ancestry to the early Brandywine mill workers, some of whose memories were preserved in an ambitious campaign of oral histories undertaken in the 1950s by the Hagley Museum. Millworker housing in dense rows remained a defining characteristic of many neighborhoods in Wilmington.

( Hagley Museum & Library)

(Library of Congress)

With nineteenth-century industry came wealth, as the Brandywine became nationally synonymous with technological revolutions in milling. Just outside Wilmington, handsome estates were built overlooking the stream, and poets and writers sang the praises of the valley, with its appealing mix of water-powered industry, picturesque riparian scenery, and tales of lore from Indian days and the Battle of the Brandywine, where the romantic young Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834) had been wounded. The culmination of these literary efforts was eventually The Brandywine, a book in the popular Rivers of America series (1941) by Wilmington-born critic Henry Seidel Canby (1878-1961), with illustrations by Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009).

But industry also brought pollution of the creek, and by the 1860s there were calls to preserve land along its banks to safeguard the health of Wilmingtonians, who drank the foul-smelling water. Brandywine Park was established in the 1880s, laced with curving roadways that followed, rather imperfectly, a plan provided by the leading landscape architect of the day, Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903). The park was the beginning of a conservation tradition that made the valley a recognized role model in watershed preservation nationwide. Headquartered at Chadds Ford, the Brandywine Conservancy, begun in 1967, expanded to hold more than 500 conservation easements over 12 percent of the watershed.

Preserving the Scenic Valley

As the du Pont family amassed extraordinary wealth—as late as the 1980s, they were one of the richest families in America—they played the key role in preserving the scenic Brandywine Valley against the looming threat of heavy industry, such as that which engulfed the lower Schuylkill, or the piecemeal suburban sprawl that jostled against Darby Creek, fifteen miles north. The Brandywine Conservancy, for example, was the brainchild of a boisterously enthusiastic du Pont descendant, George A. “Frolic” Weymouth (1936-2016). The unspoiled flavor of the region—as seen, for example, from the twelve-mile Brandywine Valley National Scenic Byway designated in 2005—owed much to the du Pont family’s traditional concern with large-scale estate agriculture, their cultivation of a pleasing landscape aesthetic, and the cherishing of historic sites.

Their special passion was gardening. America’s premier French-style formal garden flourished at the Nemours estate (1910) of Alfred I. du Pont (1864-1935), an elaborate homage to his French ancestors. A woodland garden underplanted with colorful azaleas flowed over the hillsides at Winterthur (“March Bank” garden, 1902), home of Henry Francis du Pont (1880-1969), whose collection of American antiques remains unparalleled. Under the creative eye of Pierre S. du Pont (1870-1954), the nation’s largest-ever display garden took shape at Longwood (Main Conservatory, 1921) and later became the flagship cultural attraction of the Brandywine Valley, with more than 1.5 million visitors annually. All these gardens (and associated estates of sprawling size and sumptuous elegance) were funded by industry in places far distant and especially benefited from the windfall profits that the DuPont Company enjoyed from providing gunpowder to the western front in World War I.

As the estates of what contemporaries have nicknamed “Chateau Country” were being laid out and embellished, there simultaneously flourished the Brandywine School of Art, a movement centered on Howard Pyle (1853-1911), the Wilmington-born artist who revolutionized American illustration starting in the 1880s. Pyle moved to Philadelphia to be near the leading publishing houses of the day but eventually returned to the Brandywine Valley, which he regarded as the wellspring of his art, inspiring him deeply with its historical relics, from crumbling colonial houses and mills, to rustic “worm” fences lining dirt roads through the cornfields of the unspoiled countryside, to venerable Old Swedes Church (1698-99) near the Brandywine’s mouth. A teacher at Drexel Institute in Philadelphia, Pyle brought his best students to the Brandywine Valley, founding a summer art school on the Brandywine Battlefield at Chadds Ford. His star student arrived in 1902, N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945), who shared Pyle’s near-religious devotion to the relics of America’s colonial past and settled permanently in Chadds Ford when he began his own, legendary career as the dean of American illustration.

Wyeth Tourism

N.C. Wyeth and other former students of Pyle became known as proponents of the “Brandywine school” of illustration, with a strong emphasis on rural life, the colonial heritage, and meticulously researched historical themes. His son Andrew extended the tradition right up to the twenty-first century, living and painting exclusively on the Brandywine all his life, except for summers in Maine, and developing a brooding, rather bleak style deliberately different from his father’s. The immense fame of Andrew Wyeth continued to draw tourists and plein-air painters to “Wyeth country” in the Brandywine Valley, where the Brandywine River Museum of Art amassed the world’s largest collection of Wyeth paintings, from N. C. right down to Jamie Wyeth (b. 1946), who lived and painted in the area into the twenty-first century.

First State National Historical Park promised to bring ever-more attention to the Brandywine, as an area hailed as “the Most Famous Small River in America.” But the modern Brandywine Valley’s widespread popularity also fed a surge in population growth, with upscale suburban developments peppering the hilltops and threatening to change the rural character of this historic place forever. The warnings of urbanist William H. “Holly” Whyte (1917-99) about the costs of sprawl came to pass in his native valley: traffic clogged twisty colonial roads, scenic viewsheds were violated, and invasive plants proliferated. As Chester County transformed rapidly, one encouraging sign was its open-space program, launched in 1989 and ultimately responsible for setting aside 28 percent of the county’s land. Nonetheless, a worrying symptom of overdevelopment was the markedly increased flooding of the Brandywine, culminating in a record-shattering rise of twenty feet at Chadds Ford following Hurricane Ida in September 2021. The village was inundated beneath brown water, and the Brandywine River Museum of Art suffered damage. The future brings new challenges to this famous valley that has long been loved and celebrated but has proved to be ecologically fragile in the face of modern development pressures.

W. Barksdale Maynard is the author of eight books on American history, art, and architecture, including Buildings of Delaware in the Buildings of the United States series (University of Virginia Press, 2008), The Brandywine: An Intimate Portrait (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014), and Artists of Wyeth Country: Howard Pyle, N. C. Wyeth, and Andrew Wyeth (Temple University Press, 2021). He lives in Wilmington, Delaware. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2023, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- A Pennsylvania Giant: Lukens Steel (PennState Libraries)

- Du Pont: From French Exiles to the Toast of the Brandywine (Library of Congress blog)

- Brandywine Conservancy

- Behind Ida’s destruction along the Brandywine: A 1,000-year downpour, a ‘choke point,’ and a record crest (Philadelphia Inquirer)

- Chester County's Open Space land preservation program (Chester County Planning Commission)