Children’s Aid Society of Pennsylvania

Essay

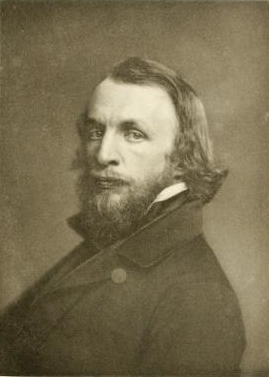

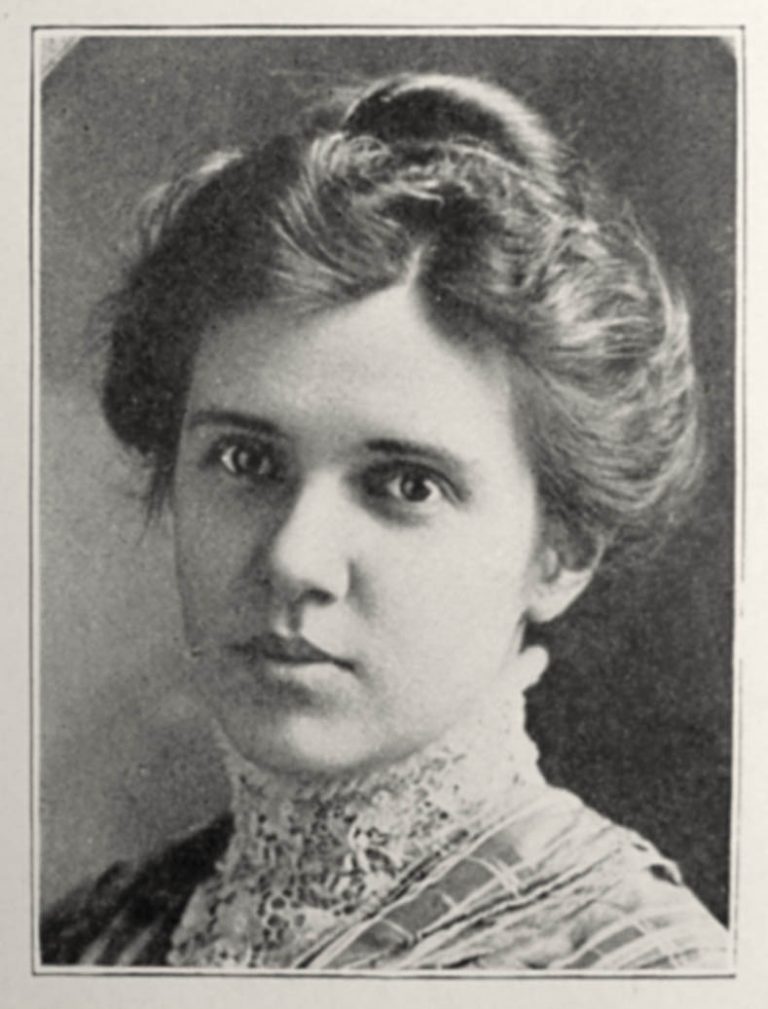

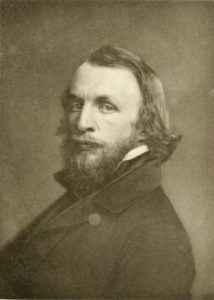

The Children’s Aid Society of Pennsylvania was founded in 1882 by a group of predominantly women volunteers to address social issues plaguing the city of Philadelphia, such as drunkenness, child homelessness, and rampant crime. Child welfare advocate Helen W. Hinckley led the charge, assisted by Cornelia Hancock (1840–1928), who had volunteered as a nurse in the Union army. The society’s primary goal was to support families, especially single or deserted mothers. It encouraged self-reliance by urging parents to contribute to their children’s expenses and by temporarily alleviating the burden of childcare so that they could find work. On occasion, the agency cared for abandoned, delinquent, or orphaned children. The Children’s Aid Society of Pennsylvania drew on the model of the New York Children’s Aid Society, created by Charles Loring Brace (1826–90) in 1853 to address similar concerns.

The nineteenth century experienced a significant increase in urbanization, industrialization, and immigration. The population of Philadelphia tripled between the years 1790 and 1830, and this growth coincided with epidemics of cholera, yellow fever, and typhoid fever, which contributed to an abundance of children who were either orphaned or abandoned. As a result of such upheaval or parental neglect, children often roamed the streets, worked as apprentices through indenture, or faced confinement to almshouses, jails, or insane asylums. The combination of crime and abandoned street children presented serious issues that social welfare advocates such as Hinckley, who had previously served as secretary at the Pennsylvania Homeopathic Hospital for Children, could not ignore. In 1883, she successfully pushed for legislation that prohibited the institutionalization of children in asylums designated primarily for adults. In 1884, the Children’s Aid Society reported that it had cared for 681 children annually, a number that grew steadily over the next fifty years.

The Philadelphia-based organization served children throughout the state until 1889, when the Children’s Aid Society of Western Pennsylvania was organized. Since the Children’s Aid Society could not accommodate all children in the region who were in need of homes and services, volunteer committees created local county branches to respond to this need. Although initially created to address an overflow from the central office, county offices became essential to operations by the 1890s. Before the creation of a centralized bureau in 1921, these local agencies reported between half and two-thirds of the cases to the central office, many of whom were children who had been contracted as indentured workers. By the mid-1930s the Children’s Aid Society reported that it provided care and services for 3,030 children annually from both Philadelphia and its neighboring counties.

The Children’s Aid Society was a pioneer in the professionalization of the field of social work during a period when foundations were established to tackle the root causes of poverty. In the first decade of the twentieth century, the field of social work evolved to include more scientific-based understandings of poverty and child development. In response to these developments, in 1908 the Children’s Aid Society began offering career training to its employees, which eventually grew into the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Work (later the School of Social Policy and Practice). The society itself also became more professional, with several prominent figures serving in managerial capacities. Edwin D. Solenberger (1876–1964), a social service administrator, served as general secretary from 1907 until 1943. John Prentice Murphy (1881–1936), a pioneer in the literature on the models of intervention and outcome assessment, joined the society in 1908. In the 1920s, Dr. Jessie Taft (1882–1960), an expert in the burgeoning field of mental hygiene, became the director of the Child Study Department, which provided mental examinations to incoming children. These advancements contributed to the agency’s mission by providing holistic care and support to children and their families.

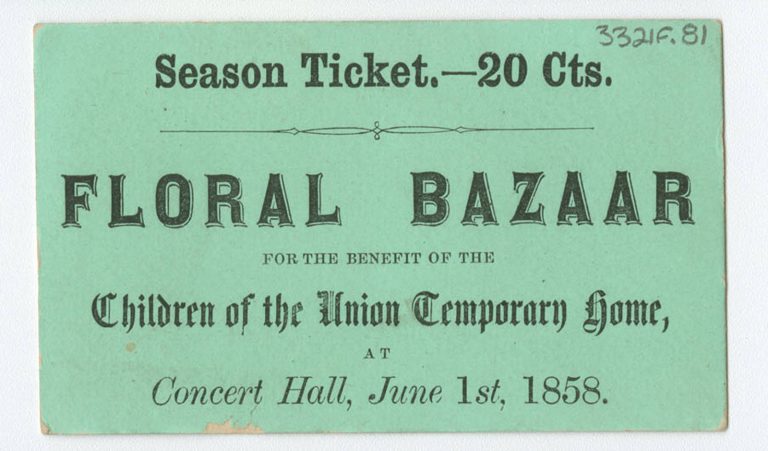

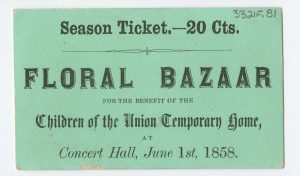

Over the years, several local child welfare agencies merged with the Children’s Aid Society. The Union Temporary Home (1856), an institution that was created specifically for poor white children, officially closed in 1887 due to financial constraints. The Philadelphia Home for Infants (1873), created for children under the age of three, also began struggling financially in the early twentieth century and eventually merged with the Children’s Bureau in 1942. The Children’s Bureau (1907) functioned as a shelter and centralized information bureau to funnel information to the more than sixty agencies that received needy children. During World War II, both the Children’s Bureau and the Children’s Aid Society helped place juvenile refugees from Europe into homes in the Philadelphia area. They merged into one organization in 1944.

From the 1950s through the late 1970s, child welfare services were typically self-contained units that focused on in-home evaluations. From the 1970s onward, local government agencies began operating under federal legislation. Similar in its mission to the Children’s Aid Society, the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act of 1980 aimed to serve children in their own homes, prevent external placement, and facilitate the reunification of families. Despite such reform, the late 1980s and 1990s experienced increases in child neglect and foster placements. In Philadelphia, agencies such as the Philadelphia Task Force for Children at Risk, the Support and Community Outreach Program, and PhillyKids Connection addressed these concerns.

Dedicated to improving and protecting the lives of children, the Children’s Aid Society of Pennsylvania was a pioneer in child welfare and advocacy. In 2008, it merged with the Philadelphia Society for Services to Children and formed Turning Points for Children, an organization dedicated to reducing child abuse and improving the lives of over nine thousand children and their caregivers. Like its predecessor, Turning Points for Children focused on providing holistic family-center programs in the interest of building community relations in the region.

Holly Caldwell received her Ph.D. in history from the University of Delaware, where she wrote her dissertation on the medicalization of deafness and deaf education reform at Mexico’s Escuela Nacional de Sordomudos (National School for Deaf-Mutes). She is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of History at Chestnut Hill College and has also taught at Susquehanna University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- 17 percent of Philly public school kids involved in child welfare, juvenile justice systems (WHYY, June 10, 2014)

- Child welfare services sue over Pa. budget deadlock (WHYY, September 16, 2015)

- Philly group finds new way to couch discussions of plight faced by homeless LGBT youth (WHYY, October 7, 2015)

Links

- "Cobb's Anti-Liquor Words Used in Exhibit," Evening Public Ledger (Library of Congress)

- The Social Welfare History Project (Virginia Commonwealth University)

- U.S. Children's Bureau - Time for a Revival (Philly.com)

- Cornelia Hancock (National Park Service)

- New York Children's Aid Society (Virginia Commonwealth University)

- Charles Loring Brace (Virginia Commonwealth University)