Franklin Institute

Essay

On February 5, 1824, a group of Philadelphians led by Samuel Vaughn Merrick (1801–70) and William Hypolitus Keating (1799–1840) met at the courthouse on Sixth and Chestnut Streets to found the Franklin Institute of the State of Pennsylvania for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts. Seeking to emulate a passion for useful science, in the spirit of Benjamin Franklin (1706–90), institute members promoted mechanic arts in and beyond the city. The institute played a significant role in fostering technological innovation through the late twentieth century. Institute members had a longstanding interest in promoting science education, and the founding of a science museum in 1934 began to reorient the institute as an important local resource for K-12 outreach.

Early members tended to be white male manufacturers and scientists. The institute’s first president, Scottish immigrant James Ronaldson (1768–1841), was the cofounder of the first American type foundry. The institute was immediately popular, and within the first year it needed its own building to accommodate the ever-growing membership. Famed architect John Haviland (1792–1852) designed the institute’s first long-term home, whose construction began June 8, 1825, at 15 S. Seventh Street. Women gained institute membership as early as the 1830s. The institute sponsored a women’s school of design from 1850 to 1853 (later the Moore College of Art and Design). In 1870, Octavius Catto (1839–71) became the first African American member of the Franklin Institute.

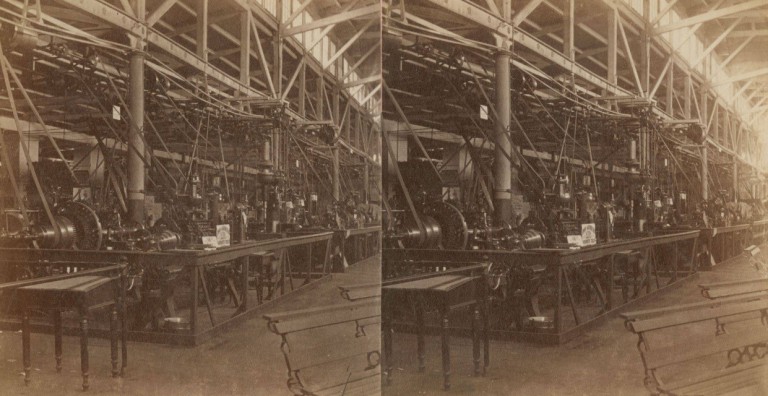

During its first century, the Franklin Institute became an important advocate for scientific research through the sponsorship of various activities and publications. It held its first exhibition in October 1824 honoring American industry at Carpenter’s Hall. Such exhibitions were held annually, and the medals and prizes awarded by the institute became a nineteenth-century standard for appraising the efficacy of a product. Many manufacturers included Franklin Institute awards in their advertising. The first issue of the Journal of the Franklin Institute appeared in 1826, chronicling new discoveries in physics, mechanical engineering, and chemistry. A variety of lecture series taught by professors employed by the institute or by traveling speakers offered practical scientific training to Philadelphia’s young men and women. By the end of the century, the institute’s reputation enabled it to negotiate on behalf of Philadelphia with the U.S. government. For example, in 1869, the Franklin Institute helped petition Congress to hold the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. In 1873 it encouraged the government to undertake a statewide geological survey, later realized as the Second Geological Survey of Pennsylvania and later, in 1886, to establish a state meteorological service in the city.

In 1930, and despite the Great Depression, the Franklin Institute, in conjunction with the Poor Richard Club, began fund-raising to build a science museum. So beloved was the Franklin Institute that they raised $5.1 million in less than two weeks. By 1934, the new museum opened on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, while its first home on Seventh Street was saved from demolition when Atwater Kent purchased the building and gave it to the city for a city history museum. This event marked a gradual shift towards reimagining the institute as an influential center for popular science education. The Parkway site included the Fels Planetarium, the second planetarium to open in the United States. One of the best-known permanent exhibits, the giant walk-through heart, opened in 1954. The family-friendly exhibit allowed visitors of all ages to explore human physiology by physically engaging with the space. Artifacts on long-term display included mechanical curiosities, such as an eighteenth-century Swiss automaton created by Henri Maillardet (1745–1830), and a significant amount of Frankliniana, including a period lightning rod.

The museum expanded in 1990, acquiring an IMAX theater, and again in 2012. In the twenty-first century, the Franklin Institute sponsored a number of successful educational programs including Science Leadership Academy (2006), a science-oriented magnet public high school with an emphasis on laptop-based learning, and the Philadelphia Science Festival (since 2011), an annual nine-day, citywide celebration of science offering activities ranging from family-friendly fun to teacher training. Although not the arbiter of scientific innovation that it was in the nineteenth century, the Franklin Institute continued a tradition of making scientific education accessible to local Philadelphians.

Jessica Linker is a doctoral candidate at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, and the recipient of fellowships from a number of Philadelphia-area institutions, including the Library Company of Philadelphia, the American Philosophical Society, and the McNeil Center for Early American Studies. Her work focuses on American women and scientific practice between 1720 and 1860. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- $10 million gift helps pave way for Franklin Institute expansion (WHYY, October 3, 2011)

- Rare dinosaur find expands Franklin Institute exhibit (WHYY, February 3, 2012)

- Work begins on Franklin Institute expansion to house 'Your Brain' (WHYY, April 5, 2012)

- As the Franklin Institute changes presidents, a look at how the science museum evolves (WHYY, June 27, 2014)

- Jurassic World has blockbuster opening weekend at Philadelphia's Franklin Institute (WHYY, November 29, 2016)