Freedom Train

Essay

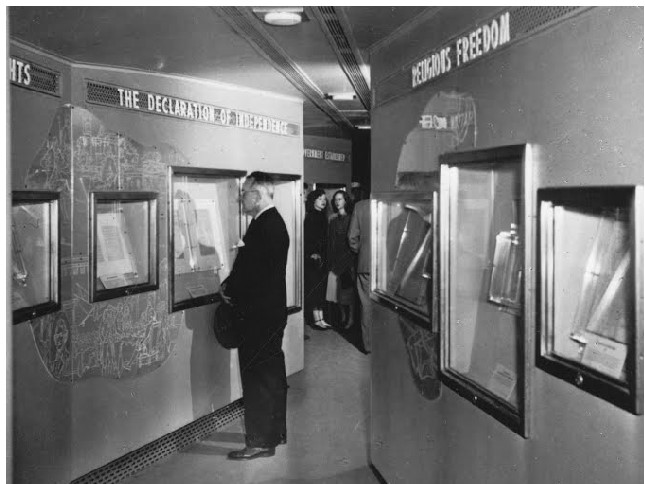

On September 17, 1947, a seven-car train arrived in Philadelphia’s Broad Street Station carrying 130 articles of American history, including documents, prints, pictures, and flags, intended to represent this history’s most important legacy: freedom. After its launch in Philadelphia, the Freedom Train went on a 29,000-mile journey to three hundred communities throughout the United States, reaching 3.5 million “passengers” who boarded the train in addition to over forty million people who attended “Re-Dedication Week” ceremonies at each stop. The Freedom Train served as an early effort to unify the American people against the encroaching threat of communism at the beginning of the Cold War.

The idea for the Freedom Train often has been attributed to Attorney General Tom C. Clark (1899-1977), who sought to devise a plan for civic revitalization to counter any disintegration of unity among Americans after World War II. Clark drew his inspiration from an aide who, after visiting an exhibit at the National Archives that contrasted Nazi documents with the charters of American liberty, was struck with the idea to send this display on tour in a specially fitted railroad car. The idea gained momentum quickly within both the public and private sectors, leading to the incorporation of a nonprofit foundation called the American Heritage Foundation (AHF), which embarked on the project that came to be known as the Freedom Train.

Three of the Freedom Train cars were supplied by the Philadelphia-based Pennsylvania Railroad and outfitted at workshops in Wilmington, Delaware, to display the historic documents. Philadelphia’s Broad Street Station was chosen as the starting point of the train’s journey because of the city’s significance as the site of the drafting and signing of the documents, especially the U.S. Constitution. The train’s departure date, September 17, 1947, coincided with the 160th anniversary of the signing of the Constitution.

Constitution Day and the arrival of the Freedom Train in Philadelphia were celebrated as part of the city’s Re-Dedication Week ceremonies, which consisted of six days of patriotic celebrations and activities, including a veterans day, a religious freedom day, a women’s day, a youth day, and three days for tours of the train. The events supported the Freedom Train’s slogan: “Freedom is Everybody’s Job!” For three days, thousands of people lined the streets of Center City to tour the train and sign their names on a Freedom Pledge Scroll. Notable local and national speakers at the Freedom Train festivities included Tom Clark, future secretary of state John Foster Dulles (1888-1959), Pennsylvania U.S. Senator Edward Martin (1879-1967), and Philadelphia Mayor Bernard Samuel (1880-1954). Clark brought a message from President Harry S. Truman (1884-1972), who emphasized the unique importance of America’s concept of personal liberty. Clark warned a crowd of youth that if Americans “don’t buckle down and work at keeping freedom in good working order, we can lose it.” Dulles’s words were more pointed, emphasizing that the battle for maintaining freedom would be won in American homes, churches, schools, and union halls.

The Freedom Train departed Philadelphia for a stop in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on September 21. More than ten thousand people turned out in threatening weather to tour the train and rededicate themselves to their American heritage in a ceremony led by Atlantic City Mayor Joseph Altman (1892-1969). Many of the attendees were children, who had spent the previous week in school learning about the significance of the rededication. The train also stopped in Wilmington, Delaware, on November 21. A reported average of one thousand people per hour visited the train, while addresses were given by Governor Walter Beacon (1880-1962), Wilmington Mayor Joseph S. Wilson (1888-1967), and Circuit Judge Paul Leahy (1904-66).

Not all Americans were receptive, however. In Philadelphia, members of the Philadelphia Committee for Amnesty to All War Objectors picketed the Freedom Train and distributed leaflets that decried the hypocrisy of displaying the documented guarantees of freedom while at the same time many Americans were being denied their right to conscientious objection. The project’s focus on the nation overshadowed this kind of local conflict, but further contradictions with the freedom message became clear later when the train reached the segregated South. The program largely succeeded in gaining African American participation despite the fact that African Americans were deliberately excluded from its planning. In southern states, the American Heritage Foundation wavered on its policy of prohibiting segregation at the exhibit, canceling stops in some cities that insisted on segregated lines and tours while stopping in others that implemented the same prejudiced policies.

Many viewed the train and the implications of its message with a degree of skepticism. However, at a time when American freedom seemed to be at risk, the Freedom Train embodied the values of the documents that it carried, created in the “cradle of liberty,” Philadelphia.

Matt Trowbridge is a graduate of Rutgers University-Camden (2015) and is pursuing his Master’s in Library and Information Science at Rutgers’ School of Communication and Information. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History