Great Depression

By Roger D. Simon | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

The Great Depression, which lasted from 1929 to 1941, was characterized in both the Philadelphia region and the nation by a severe contraction in all levels of economic activity, massive unemployment, widespread bank failures, and sharp price deflation. Many people lost their life savings and their homes. Untold thousands went hungry; some starved. It led to powerful labor unions, a change in political alignments, and a new conception of the role of government.

The Depression began in Philadelphia even before the stock market crash. In April 1929 city-wide unemployment stood at 10 percent; 30 percent of the jobless had been idle for six months or longer. The textile industry, the city’s largest manufacturing sector, suffered competition from plants elsewhere in the region, particularly Reading, as well as in the South. Although the garment industry did well, seasonal layoffs and low wages characterized both the textile and apparel sectors. Production of knit goods, radios, and motor vehicle parts helped to bolster employment, but as soon as the national economy began to falter, Americans cut back on the purchase of manufactured goods.

From the end of 1929 to the spring of 1933 the national and local economy spiraled downward. The decline was staggering; regional manufacturing output plummeted 45 percent, while factory payrolls fell by 60 percent; retail sales sank by 40 percent. Construction went into free fall, dropping 84 percent. Unemployment rose inexorably. By April 1930, 135,000 Philadelphians were jobless with another 46,000 working only part time. A year later, the number of unemployed approached 250,000, more than a quarter of the workforce. The slide continued until March 1933; by then, only 40 percent of the workforce was employed full time, the rest worked only part time or not at all. Although the entire region was hard hit, the city suffered the worst. In 1930 Philadelphia’s unemployment rate was twice that of Chester and Montgomery counties. Manufacturing workers had higher rates of unemployment than did those in white collar and service occupations. The foreign born and African Americans, because they were concentrated in manufacturing and low skilled jobs, and because of outright discrimination, sustained particularly high levels of joblessness.

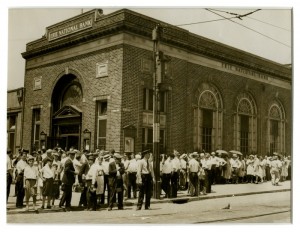

The sinking economy jeopardized an overextended banking sector. As property owners defaulted on mortgages, banks found themselves in trouble. Between 1929 and 1933 more than half of the commercial banks and building and loan associations in Philadelphia failed. Nor were bank failures and foreclosures limited to the cities. In Camden County, banks closed in every single municipality. Since there was no federal deposit insurance before 1933, thousands of people lost their savings. The largest bank failure was that of Bankers Trust Company, which had 100,000 depositors.

Republican Machine Dominated

Government in Philadelphia, as well as most of the region, was firmly in the hands of the Republican Party. An entrenched and corrupt Republican machine completely dominated the city. Party officials and wealthy local elites shared the conservative ideology of President Herbert Hoover and his animus against government intervention and publicly-funded charity. It was this doctrinaire laissez-faire outlook that informed the city’s response to the Depression and to calls for public relief under mayors Harry Mackey (1928-32) and his successor, J. Hampton Moore (1932-36).

The Depression took a devastating toll on the people. With increasing despair, men pounded the pavement in search of any work at all. After exhausting personal savings, the unemployed ran up debts to local store owners, and skipped rent, mortgage, utility, and tax payments. Thousands went hungry. Some turned to begging, petty theft, and scavenging for discarded or spoiled food. Further aggravating conditions, banks foreclosed on delinquent homeowners. Between 1929 and1933, in Philadelphia alone, over 90,000 families lost their homes. Evicted families, when they could, moved in with relatives, whole families cramming into one or two rooms. Some squatted in abandoned houses under appalling conditions. Makeshift homeless encampments sprang up, derisively named Hoovervilles after the president, with the largest in Philadelphia along the east bank of the Schuylkill River near the Museum of Art. Pride and self-esteem melted away.

At first, private charities tried to alleviate the suffering. Soup kitchens and bread lines quickly appeared in churches, missions, empty stores, settlement houses, and fire stations–over eighty in Philadelphia alone. The food was free, but the humiliation of standing in line, advertising one’s need, was a high price to pay. By the fall of 1930, the magnitude of the crisis overwhelmed the efforts of the private charities. Philadelphia had discontinued direct assistance to the needy in 1879. In late 1930 Mayor Harry Mackey appointed a Committee on Unemployment led by prominent banker Horatio Gates Lloyd that coordinated a massive city-wide volunteer relief program which drew national attention. Over the next two years it provided vouchers for food and fuel, hot breakfasts to school children, a homeless shelter for 3,000 men, and organized used clothing drives and work relief projects. The city and state contributed several large grants, but most of the money came from private donations. In June 1932, while aiding 57,000 families, the Gates committee ran out of funds and shut down entirely, laying bare the failure of a voluntary solution. In September, Pennsylvania stepped in and funded a system of countywide relief boards, but during that desperate summer of 1932 there was very little help for anyone. Elsewhere in the region, Wilmington and Camden County made similar efforts. Wilmington was particularly eager to avoid street begging and soup kitchens that might tarnish the city’s image.

From the outset, labor activists called for government action to alleviate suffering. Communists, a small but highly committed group, tried to galvanize the unemployed to action, particularly among the textile workers in the Kensington-Richmond areas. The demands were hardly radical: public works jobs, adequate relief grants, and a halt to evictions. In February 1930, a small group rallied at Philadelphia City Hall which police broke up, sending dozens to the hospital. A second rally at City Hall a week later drew twice the crowd, but remained peaceful. In March, after a strikebreaker killed a worker during a bitter strike against Aberle hosiery mill, the victim’s funeral drew thousands and became the largest protest against conditions yet seen. Over the next two years, labor leaders organized workers in Kensington-Richmond and other neighborhoods hard hit by the Depression. Communist involvement allowed the mayor and newspapers to dismiss the protestors as “reds”; in reality, the Communists attracted few adherents.

Battle of Reyburn Plaza

Meanwhile, increasingly militant workers, particularly in Philadelphia, took aggressive steps to help themselves. In June 1932 over 1,000 textile workers founded the Northeast Unemployed Citizens League which resisted evictions and distributed food to its members while calling for unemployment insurance and old age pensions. In response, a frightened Mayor Moore established a police department “red squad.” In August, 1932, when 1,500 “hunger marchers” rallied for jobs at City Hall, Moore sent the police to disperse the crowd in what came to be known as the “Battle of Reyburn Plaza.” After badly beating the organizer they arrested him for inciting a riot. Although such demonstrations struck panic into the hearts of many elites, the growing ranks of the destitute evidenced little militancy. They were too fatalistic or simply too ashamed to actively clamor for help.

Mayor Moore seemed oblivious to the human crisis. In January 1932, after a drive through hard-hit South Philadelphia, he famously concluded, “No one is starving in Philadelphia,” although people clearly were. In 1935, opposing slum clearance and public housing, he asserted: “this city is too proud to have slums,” despite the abysmal conditions in which many lived. Under his tenure the city contributed nothing to relief of the needy. However, the decline in property values meant a sharp drop in city revenue, and Moore was determined to maintain the city’s credit without raising tax rates. He slashed the city’s payroll, and avoided default, but Philadelphia’s financial situation remained grave throughout the decade, providing an excuse to do little for the impoverished.

The calamity of the Depression and the failure of the Hoover administration to provide either relief or to halt the decline resulted in the beginning of a long-term political realignment in Philadelphia and Camden. At first, the shift affected national more than local elections. In Philadelphia in the 1920s the Democratic Party was so weak and ineffectual that the Republicans were secretly paying the rent on their headquarters. In 1931 and 1932 contractors John B. Kelly and Matthew McCloskey, real estate developer and banker Alfred M. Greenfield, and newspaper publisher David Stern led the effort to build a new Democratic coalition around blue-collar workers, particularly eastern and southern European immigrants and African Americans. In November 1933, because of the popularity of Roosevelt’s New Deal, and possibly because the US Justice department sent federal marshals to monitor the voting, Philadelphia Democrats carried two key city-wide races, electing the city treasurer and S. Davis Wilson as controller. The following year Democrats captured three congressional seats in Philadelphia. George Brunner pursued a similar strategy in Camden and gained several seats on the city commission in 1935.

In 1935, the Democrats in Philadelphia had a chance to capture the mayor’s office for the first time in fifty years. Both Kelly and Wilson sought the Democratic nomination, but when Kelly got the nod, Wilson switched parties and narrowly won as a Republican, although fraudulent vote counting possibly made the difference. Wilson did promise to cooperate with the New Deal. In 1936, Roosevelt carried the city by over 200,000 votes, and Democrats won all seven congressional seats. Roosevelt also swept the other regional cities. In national politics, the shift to the Democratic Party was complete. Never again would a Republican presidential candidate carry Philadelphia, and rarely would the GOP even win a congressional race there. However, while a Democrat was elected to Philadelphia City Council for first time in sixteen years, that was the peak of Democrats’ local prospects in the decade. The Republican machine staggered on until 1951.

Relief and Recovery

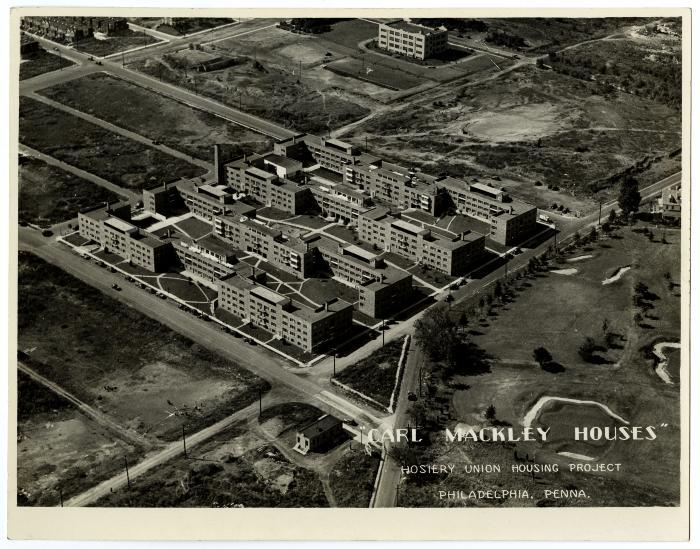

The New Deal, launched by President Franklin D. Roosevelt beginning in March 1933, established programs for relief and economic recovery. Federal aid for the most needy, administered through local agencies, began to flow almost immediately. At its peak, in April 1935, the Philadelphia County Relief Board provided aid to 105,000 families, spending a million dollars a month. In December 1936 the Board still aided 14 percent of the population. By comparison, in the Pennsylvania suburban counties, between 5 and 8 percent were getting aid. In addition, work relief and public works programs employed thousands. The Public Works Administration (PWA) funded projects around the region, notably the innovative Carl Mackley housing project in Philadelphia, the high-speed commuter rail line to Camden, and new high schools in Camden County and Wilmington.

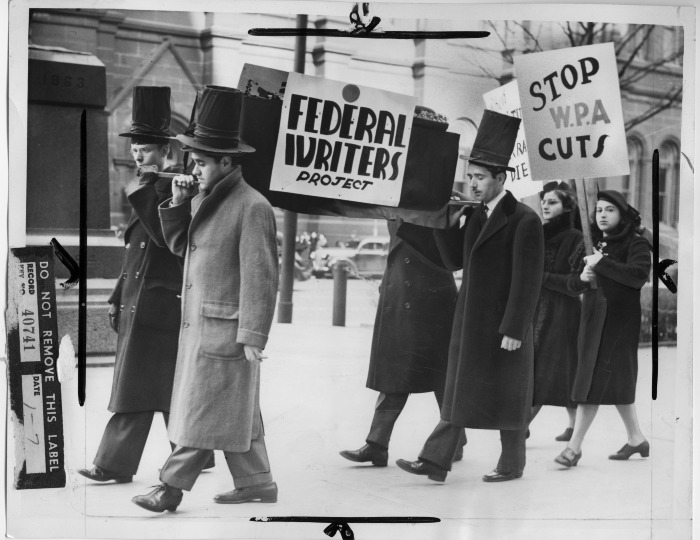

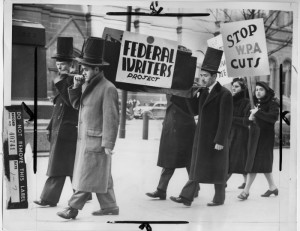

The work relief programs, which required local government contributions, were more contentious. The Civil Works Administration (CWA), which operated in the winter of 1933-34, was followed in 1935 by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). In Philadelphia Mayor Moore and City Council, demonstrating intense Republican antipathy to any federal interference and to Roosevelt’s New Deal especially, opposed cooperating with CWA until the newspapers and businesses exerted pressure on the city to participate. CWA then put 25,000 local people to work. In 1935, Moore, this time with stronger support from the Republican establishment, refused any funds for WPA projects. Consequently, 12,000 city residents worked for WPA on projects in the suburbs. Philadelphia did not participate in WPA until the new mayor, S. Wilson Davis, took office in January 1936; at its peak, later that year, WPA employed 48,000 in the city. In Camden officials were eager for WPA projects.

New Deal work relief and housing programs not only provided employment but altered the landscape of the region’s cities and suburbs. CWA and WPA workers paved streets, improved parks, built or repaired public buildings (such as schools, libraries, police and fire stations), and laid or fixed water, sewer, and gas mains. Musicians and actors gave free concerts and plays. WPA workers offered recreational programs, ran day care centers, taught adult literacy, and catalogued and preserved public records, among numerous other projects. PWA and WPA, in collaboration with the states, built new highways and paved numerous rural roads. To deal with the crisis of foreclosures and to revive the housing industry the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) offered long-term refinancing to homeowners and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) insured loans for new and renovated homes, although residential construction remained far below 1929 levels. Meanwhile, racially discriminatory policies in FHA insurance tightened racial segregation within the cities and between the city and the suburbs.

The New Deal also initiated slum clearance and public housing to provide decent housing for thousands of families. Controversy swirled around finding suitable sites and particularly accommodating housing for African Americans. The site for the Richard Allen Homes, in a dense African American neighborhood of Lower North Philadelphia, revealed the extreme conditions in which so many Black residents lived. Two-thirds of the houses lacked indoor plumbing and about half had no central heat. There as elsewhere public housing units were constructed on a “no-frills” basis with small rooms and no closet doors. The initial tenants, carefully screened, were all the upwardly mobile working poor. All the projects were racially segregated. The Republican establishment never approved of public housing, and when Robert Lamberton became mayor in 1940 the city ceased cooperating with the Housing Authority.

Uneven Social Costs

The social costs of the Great Depression were not spread evenly. No group suffered more during the decade than African Americans. In 1931, Black unemployment in Philadelphia exceeded 40 percent; by 1933 it had reached 50 percent. Comprising 13 percent of the city’s population in 1936 they accounted for 40 percent of those on relief. The figures are similar for the region’s other cities. Because of their desperate plight, Black people were particular beneficiaries of New Deal work relief programs. In Philadelphia, Camden, and Wilmington a small percentage of Black families were also able to benefit from public housing projects opened at the end of the decade.

Until the Great Depression Philadelphia was known as a militantly anti-union city, but as the economy improved factory workers took the initiative to build a strong labor movement. In addition, under the New Deal’s National Industrial Recovery Act (1933-35) and the Wagner National Labor Relations Act, passed in 1935, federal support clearly shifted toward workers. In the summer and fall of 1933, workers joined unions at such firms as the Budd Company, Freihofer’s Bread, Westinghouse Turbine, Atwater-Kent Radio, and, notably, at Philco Radio where they won a strong contract. Across the river gains occurred at major Camden employers Campbell Soup, New York Shipbuilding, and RCA-Victor. Using recreation, picnics, dances, and newspapers, unions built solidarity across skill, gender, racial, and ethnic lines. In 1933 and 1934 workers in several unions experimented with a radical new tactic, turning off their machines and standing or sitting in place inside the factory. They called these actions “pulling a Ghandi” after the great Indian protest leader; later they were known as sit-down strikes. By 1935 Philadelphia union locals claimed 250,000 members.

The biggest union breakthroughs came in 1936 and 1937. Mayor Wilson signaled a new attitude when he appointed a union lawyer as city solicitor and, unlike his predecessors, sympathized with striking workers. He established his own labor board and worked hard to resolve disputes. In 1937, workers at Midvale Steel in the Nicetown section joined the newly formed Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) while others conducted sit-down strikes against Apex Mills and Exide Battery. When the city made no effort to evict the strikers, a strike wave rippled out all across the city as workers finally found their strength in numbers. Unlike earlier in the decade, police did little to protect strikebreakers. Quickly the rejuvenated labor movement had become a major force in the economic and political life of the city.

Under the impetus of New Deal spending and a cautious optimism the national economy slowly improved after 1933, and by 1937 manufacturing output had almost returned to pre-Depression levels. But the recovery was precarious, and in late 1937 output fell sharply and unemployment rose again. Region-wide the manufacturing index fell 23 percent in a year and unemployment quickly shot up, reaching almost 25 percent in the city in early 1938. Late in 1938 the economy began to revive, partly because of heavy federal spending on military preparedness. When New York Shipbuilding started to build warships Camden’s economy picked up. In 1940 the region received 11 percent of all federal military spending, and by December manufacturing output finally surpassed 1929 levels. But the recovery remained uneven. Philadelphia’s unemployment rate still stood at 17 percent, not counting another 2.7 percent employed by WPA. Among African Americans the situation remained much worse: 29 percent sought work while another 6.8 percent relied on WPA. As late as October 1941, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported 160,000 city school children undernourished.

Changing demography

The decade also witnessed important demographic changes. For the first time the population of Philadelphia and Camden fell. The decline was only 1 percent, but in the surrounding counties the population rose as suburbanization accelerated across the region. Although Wilmington grew by 5.5 percent the balance of New Castle County grew even faster. In Philadelphia the African American population rose from 11.3 to 13 percent, a net increase of 31,000, while the identified white population fell by 150,000. In Camden, the Black population rose to 11.9 percent; in Wilmington to 12.7 percent.

The Depression took its toll in many ways, both visible and unseen. The 1930s was a decade of lost opportunities. Along with idle plants were thousands of idle workers. Some middle-aged men who lost their jobs never worked again. Couples delayed marriage, and the birthrate fell. Malnutrition and neglected medical and dental care affected people’s health. The cities became shabbier; broken streetlights and potholes remained unrepaired for years. The percentage of families that owned their homes fell sharply, while those able to hold onto their properties deferred repairs and maintenance. Children did stay in school longer, but primarily because teenagers had few job prospects.

The Great Depression also changed the region in fundamental ways. As people turned to public agencies for relief and jobs, many citizens embraced the idea of a strong federal government to maintain prosperity. A large and powerful organized labor movement arose that provided dignity and economic security for working people. The Republican Party lost its grip on local governance and a competitive two party politics emerged. New Deal spending across the region improved the infrastructure of transportation, parks, recreation, culture, public health, housing, and education. Still, the eventual recovery could not compensate for the years of hunger, cold, and discouragement.

Roger D. Simon is professor of history at Lehigh University. He is the author of Philadelphia: A Brief History (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania Historical Association, 2003). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Reprinted and adapted by permission from Roger D. Simon, “Philadelphia during the Great Depression, 1929-1941,” Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Closed for Business: The Story of Bankers Trust During the Great Depression.

Gallery

Links

- WPA Projects in Philadelphia (The Living New Deal)

- Closed for Business: The Story of Bankers Trust Company During the Great Depression (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- The Human Impact of Bank Failures (Historical Society of Pennsylvania Unit Plan)

- Redlining in Philadelphia (Amy Hillier, University of Pennsylvania)

- The New Deal Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)