Independence National Historical Park

By Charlene Mires | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

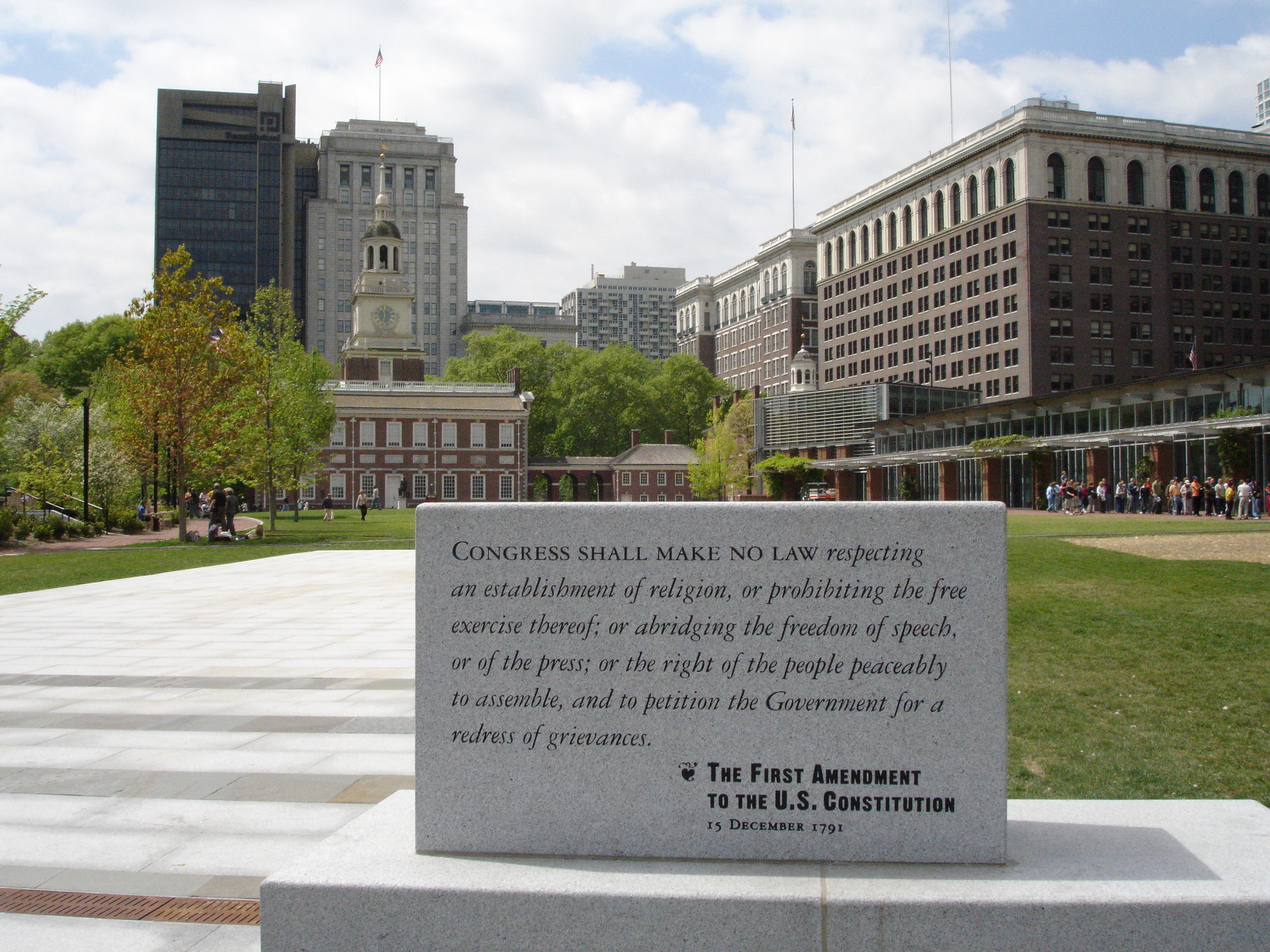

Encompassing fifty-four acres in Center City Philadelphia, Independence National Historical Park preserves and provides access to Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell, and other sites associated with the American Revolution and early American history. Authorized by Congress in 1948 in response to lobbying by Philadelphians, creation of the park transformed an aging commercial district into a series of plazas and landscaped squares and enhanced Philadelphia as a tourist destination.

Proposals to create expanded parks around Independence Hall originated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as Philadelphians, especially architects and members of hereditary societies, became unsettled by the contrast between the eighteenth-century landmark and the modern city. Their desires to safeguard the birthplace of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution increased during the period of patriotism that accompanied World War I and World War II.

In 1942, Judge Edwin O. Lewis, a member of the Sons of the American Revolution, formed the Independence Hall Association, a group dominated by civic-minded professionals who lobbied successfully for creation of a state park (Independence Mall) in the three blocks north of Independence Hall and a national park extending three additional blocks east. Later united as Independence National Historical Park, these six blocks were cleared of all structures not regarded as “historic,” leaving primarily eighteenth-century buildings as well as the Second Bank of the United States, notable for its role in the Bank War between President Andrew Jackson and the bank’s president, Nicholas Biddle.

Park Service Takes Control

When Congress authorized the national park, it defined its purpose as “preserving historic structures and properties associated with the American Revolution and the founding and growth of the United States.” This guided the work of the National Park Service, which took over administration of Independence Hall from the City of Philadelphia in 1951 and embarked on an extensive program of research and restoration.

The patriotism of the Cold War era, combined with the family focus created by the Baby Boom and the popularity of automobile vacationing, brought increasing waves of tourists to Philadelphia to see historic sites. At the same time, the expanded open spaces around Independence Hall attracted local uses, including festivals and celebrations but also demonstrations and dissent. Because of its association with the nation’s founding principles, Independence National Historical Park became a place for demonstrating for civil rights for African Americans, women, and gays and lesbians, and it was a site of sharp conflict between demonstrators and counter-demonstrators during the Vietnam War.

The demands of tourism created change in and around the park. To better serve the steady flow of visitors, in 1973 the National Park Service instituted a policy of guided tours of Independence Hall, ending a longtime local practice of passing informally through the building to touch the Liberty Bell. Because of the bell’s popularity, it was removed from Independence Hall to its own pavilion during the Bicentennial celebration of 1976 and then to the much larger, exhibit-filled Liberty Bell Center in 2003.

Campus of Tourism and Civic Education

For the Bicentennial, the park also gained a modern visitor center at Third and Chestnut Streets; this too was replaced by a larger Independence Visitor Center at Sixth and Market Streets, opened in 2001 and emphasizing not only the nearby historic sites but also visitor destinations throughout the region. The Liberty Bell Center and Independence Visitor Center, together with the National Constitution Center that opened in the northernmost block of the park in 2003, transformed the Cold War-era plazas of Independence Mall into a campus devoted to tourism and civic education.

Additional changes resulted from local activism. In 2002, an article in Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography written by Edward Lawler Jr., a member of the Independence Hall Association, called attention to the history of the long-demolished President’s House and its site at Sixth and Market Streets near the planned Liberty Bell Center. Park management initially resisted the Independence Hall Association’s call to mark the footprint of this site of the Executive Branch under George Washington and John Adams, but Lawler’s article aroused public interest in the presence of slavery in Washington’s household.

Local historians, journalists, and African American groups such as Avenging the Ancestors Coalition and Generations Unlimited joined the pressure on the National Park Service to acknowledge the convergence of liberty and slavery on the doorstep of the Liberty Bell. In 2010, after long struggle, a memorial opened to mark the footprint of the house and inform visitors about the first “White House” and all of its occupants. By that time, new guidelines for interpretation also stressed that in addition to being an important site of the American Revolution, Independence National Historical Park offered opportunities to engage with the promise and paradox of liberty.

Charlene Mires is Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden and author of Independence Hall in American Memory (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University.