Industrial Workers of the World

By Peter Cole

Essay

In the early 1900s thousands in greater Philadelphia belonged to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)—a militant, leftist labor union. Local 8, which organized the city’s longshoremen, was the largest and most powerful IWW branch in the Mid-Atlantic and the IWW’s most racially inclusive branch. Indeed, there might not have been a more egalitarian union anywhere in the nation in the early twentieth century. Known as Wobblies, these early union activists also organized Philadelphians in other industries, especially textiles and metal making.

Founded in 1905, the IWW believed that capitalism was inherently unjust, resulting in the oppression of the great majority (workers) by a tiny, wealthy elite (employers). According to the IWW preamble, these groups “shared nothing in common.” Hence, the Wobblies called for revolutionary changes to create a more just society where everyone could enjoy the fruits of industrialization.

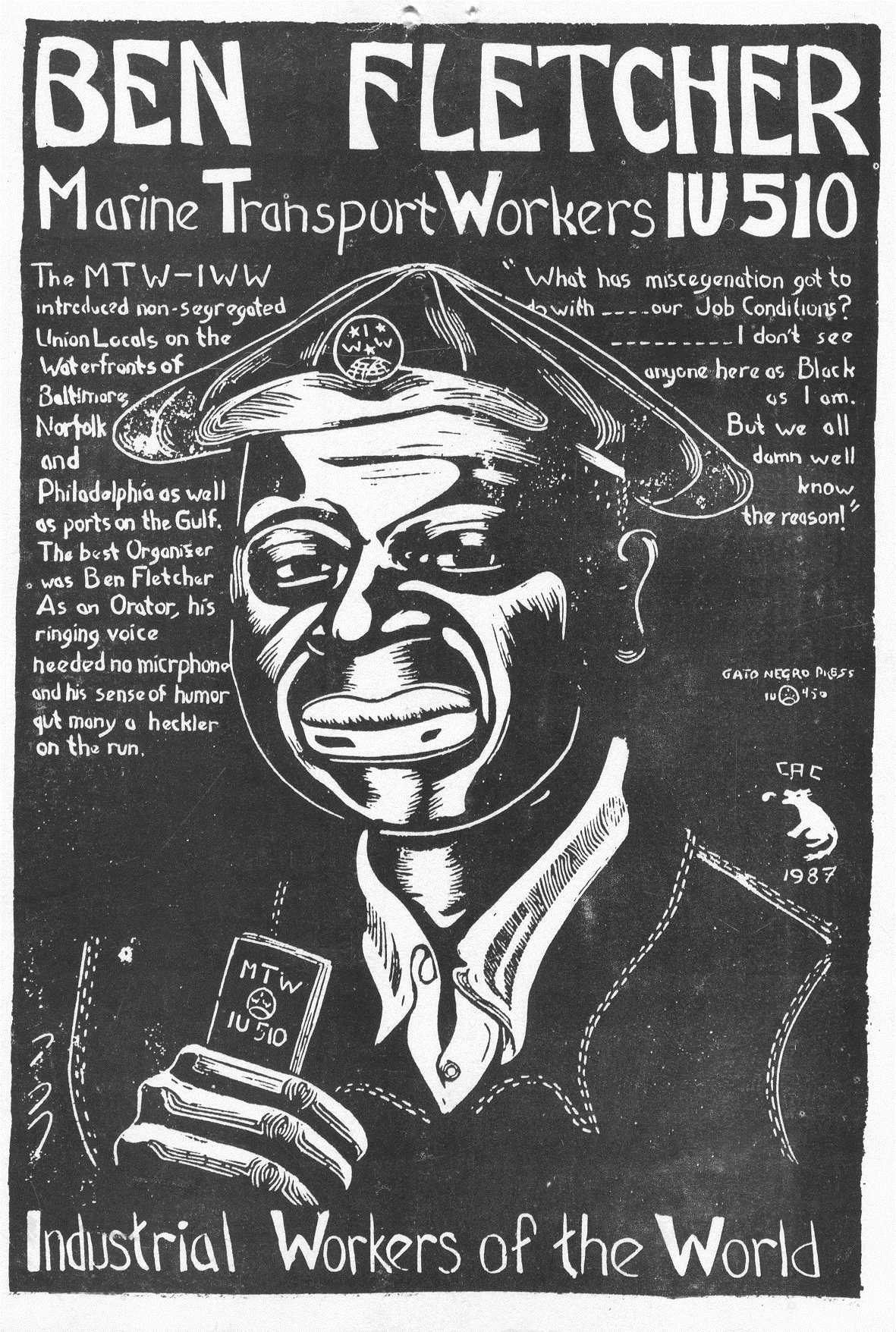

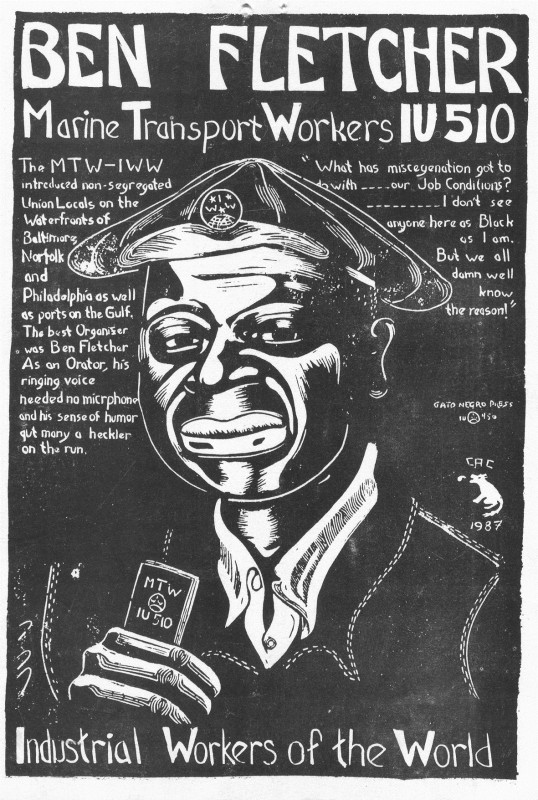

Shortly after its founding, workers in Philadelphia’s largest industry, textiles, started joining the IWW, as did those in textile centers across southeastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey, especially Paterson. Similarly, Philadelphia Wobblies maintained ties to Chester, Camden, and Wilmington. Many renowned Wobblies spoke in Philadelphia, including Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, “Big Bill” Haywood, John Reed, Arturo Giovannitti, and Carlo Tresca. However, the most important leader and greatest speaker was the locally-born African American dockworker, Ben Fletcher (1890-1949).

Thousands of Longshoremen

As one of America’s busiest ports, thousands of longshoremen toiled on both sides of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, loading everything from Baldwin locomotives to Stetson hats and unloading unrefined sugar from Cuba and coal from nearby mines.

Reflecting the city’s diversity, the city’s roughly five thousand longshoremen in 1913 were about one-third African American, a third Irish and Irish American, and a third Europeans, especially Lithuanians and Poles. Employers counted on racism and xenophobia to keep workers from unionizing. However, thousands struck that year and quickly joined Local 8 because it practiced equality by insuring, among other things that a member of every major ethnic group was represented on the negotiating committee.

The IWW’s militant tactics worked. Over the next decade, Local 8 dominated area labor relations because its members proved willing to fight for better conditions. Predictably, the empowered longshoremen experienced intense opposition from employers and the government (including the wartime arrests of Fletcher and other leaders on bogus charges of “espionage and sedition”). Beyond winning raises and improving work conditions, Local 8 also integrated work gangs, gatherings, and leadership posts—all unprecedented.

Employers Resort to Lockout

In 1922 employers taking advantage of postwar America’s worsening labor and race relations, “locked out” Local 8 members and broke their hold. This pushback was part of the first, national “Red Scare,” also signaling a backlash against the growing number of African Americans in the area. Locally and nationally, the IWW went into decline, but its ideals persisted. When the more conservative International Longshoremen’s Association returned unionism along the Delaware River, it had to acknowledge the power of African Americans. Further, the Wobbly commitment to ethnic, gender, and racial inclusion regardless of craft or skill was championed in the 1930s by the Congress of Industrial Organizations.

Although the IWW never was as strong or large in Philadelphia, or elsewhere, after the 1920s, the organization and its ideals lived on, revived by activists across the country in the 1960s and, in Philadelphia, in the 1980s. Indeed, in the last few decades, Wobblies continued to demonstrate impressive passion: to its still-radical commitment to equality across all lines; use of direct action tactics (on the job and in the streets); and brilliant use of language to skewer the status quo in song, posters, and later on the Internet.

In the 1980s, a small but impressively organized community of Wobblies, anarchists, and other leftist radicals established beachheads in West Philadelphia, including squatting in abandoned row-houses, later taking ownership of some and turning them into collectively-owned properties. Local Wobblies also set up a bookstore in West Philadelphia and were active in the Occupy Philly encampment at City Hall in 2011. As in numerous other cities in the US and beyond, Philadelphia’s IWW persisted, still deeply committed to charting a path to a post-capitalist, post-racist world.

Peter Cole is a Professor of History at Western Illinois University in Macomb. His current research compares how longshore workers in Durban, South Africa and the San Francisco Bay area participated in the civil rights and anti-apartheid movements as well as how they responded to radical technological changes in global trade. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History