Opera and Opera Houses

By Jack McCarthy | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Opera has played an important role in Philadelphia arts and entertainment since the mid-eighteenth century. The city has long been a key center for opera and holds several important distinctions in opera history, including being the site of the first serious opera performances in America, birthplace of the first major American opera composer, and home to the nation’s oldest continuously operating opera house.

The term “opera” has been used to denote several types of musical theater in America over the centuries: grand or serious opera, ballad opera, operetta, and even Ethiopian opera, the latter another name for blackface minstrelsy. With some notable exceptions, grand opera—the type of large-scale musical theater production that has generally come to define to the term “opera”—was rarely performed in America until the 1820s.

The most popular form of musical theater in early America was ballad opera. An English form of entertainment that was similar to musical comedy, ballad operas were lighthearted plays with satirical songs and dances inserted, usually performed as “after pieces” following a dramatic play. The Beggar’s Opera, the best-known ballad opera of the eighteenth century, was probably on the bill in the first documented theater performances in Philadelphia, given by a traveling English troupe in January 1749 in a converted warehouse on the Delaware River near Pine Street.

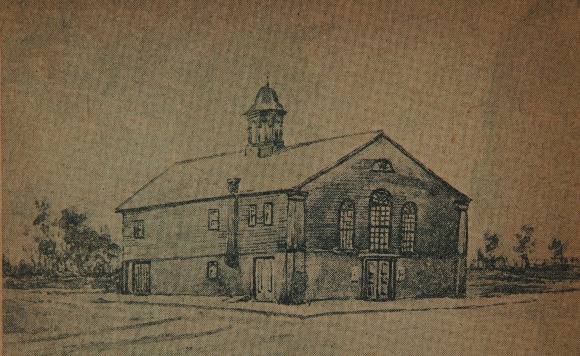

In April 1754, another English theater troupe, the Hallam company, began giving plays and ballad operas in the same warehouse and then in 1759 erected a temporary theater on the southwest corner of Cedar (later South) and Hancock Streets, between Front and Second Streets. In 1766 the Hallam company built the Southwark Theatre, the first permanent theater building in America, on Cedar Street west of Fourth Street (later the southwest corner of South and Leithgow Streets). Cedar Street was then the southern boundary of the city of Philadelphia and the theater was deliberately built on the south side of the street, just outside the city limits and beyond the jurisdiction of conservative Quakers and city officials opposed to theater on moral grounds. The Southwark Theatre was the primary venue for theater and ballad opera in Philadelphia until the mid-1790s.

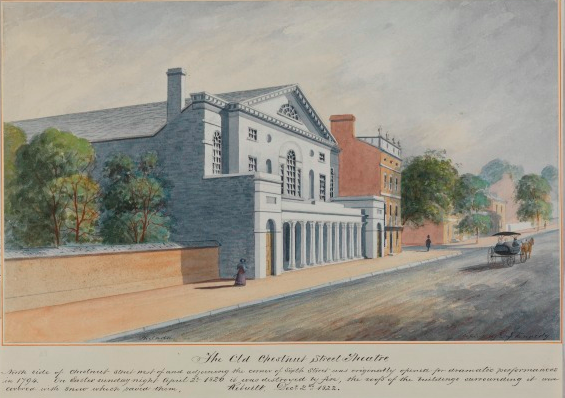

Chestnut Street Theatre

In 1793, two immigrant English impresarios, actor Thomas Wignell (1753–1803) and musician Alexander Reinagle (1756–1809), built the Chestnut Street Theatre on the north side of Chestnut Street west of Sixth Street, although its opening was delayed until the next year after yellow fever struck the city. The nation’s most elaborate theater at the time, the Chestnut Street Theatre became a major center for opera. Ballad operas still predominated in this period, usually productions written in England and adapted for American tastes. Benjamin Carr (1768-1831), an English musician who settled in Philadelphia in 1797 and became a prominent performer, composer, and music publisher, wrote The Archers in 1796, the first musical drama to be written and professionally performed in the United States. Carr and Reinagle were prolific Philadelphia composers whose ballad operas and other compositions were performed frequently in the city in the federal period.

While ballad operas were the usual fare in eighteenth-century Philadelphia, there were occasional musical theater productions of a more serious nature, including performances that represented significant milestones in American opera history. In early 1757 the College of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania) gave several performances of the musical drama The Masque of Alfred by English composer Thomas Arne (1710–78), as adapted and directed by college provost William Smith (1727–1803) and performed by his students in the College Hall at the southwest corner of Fourth and Arch Streets. A dramatic production that integrated acting, music, scenery, and costumes, some historians consider The Masque of Alfred the first presentation of a serious opera in America. One of the student performers, Francis Hopkinson (1737–91), later became a key figure in Philadelphia’s musical life, as well as an important political leader and a signer of the Declaration of Independence. His oratorical work, The Temple of Minerva, was given an elaborate performance in Philadelphia in December 1781 in celebration of America’s alliance with France in the Revolutionary War. Featuring music and dramatic acting to a Hopkinson libretto that was sung throughout (with no spoken dialogue), The Temple of Minerva has been called the first grand opera in America.

Their significance notwithstanding, The Masque of Alfred and The Temple of Minerva were isolated dramatic musical presentations; they were not part of a broader trend toward serious or grand opera, which did not come to Philadelphia on a regular basis until the 1820s. Grand opera, characterized by large casts and orchestras, lavish stage effects, plots based on dramatic or historic themes, and a multi-act libretto sung throughout, originated in Italy in the late sixteenth century and gradually spread to other parts of Europe. Lorenzo Da Ponte (1749–1838), the Italian librettist who wrote the librettos for several of the best-known operas by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91), moved to the United States in 1805 and lived in Philadelphia for a period in the 1810s. Da Ponte lamented the predominance of English ballad opera in the city, and nation, and in later years actively worked to bring grand opera to America.

The earliest attempt at true European grand opera in Philadelphia was the December 1818 production at the Chestnut Street Theatre of The Libertine, an English adaption of Mozart and Da Ponte’s Don Giovanni. Such adaptations—with librettos translated into English—were common in early nineteenth-century America. The Libertine proved very popular in Philadelphia; after the Chestnut Street Theatre burned down in March 1820 and was being rebuilt, The Libertine was performed several times at the Walnut Street Theatre, which was built as a circus at the northeast corner of Ninth and Walnut Streets in 1809 and converted to a theater three years later. Primarily a venue for plays, the Walnut Street Theatre also hosted some grand opera in the nineteenth century.

Musical Fund Hall

In addition to the Walnut and Chestnut Street Theatres (the latter having reopened on the same site in December 1822), several other venues presented opera in antebellum Philadelphia. Musical Fund Hall, built by the Musical Fund Society of Philadelphia in 1824 on Locust Street west of Eighth Street, was primarily a hall for symphonic concerts and recitals, but occasionally presented grand opera, including the American premiere of Mozart’s The Magic Flute in February 1841. Likewise, the Arch Street Theatre, built in 1828 on the north side of Arch Street west of Sixth Street, was mainly a venue for plays, but also hosted opera performances. The National Theatre, which opened on Chestnut Street east of Ninth Street in 1840, and P. T. Barnum’s Museum, which opened two blocks away at the southeast corner of Seventh and Chestnut Streets in 1849, both presented operas for a brief period before burning down, the latter in 1851 and the former in 1854. The Chestnut, Walnut, and Arch Street theaters remained the primary opera venues in Philadelphia for most of the antebellum era.

The operas presented at these theaters in the 1820s through 1850s were a mix of productions by local resident companies and performances by touring troupes from Europe and New Orleans, the latter the first American city in which grand opera gained a foothold. Grand opera gradually replaced ballad opera in popularity in this period, with the latter largely disappearing by midcentury. From 1827 to 1833, John Davis (1773–1839), a French-born New Orleans opera impresario, brought his company to Philadelphia and other northern cities each summer, presenting French opera in French. In the 1830s, Italian troupes, some managed by Da Ponte, began visiting Philadelphia, while local companies began presenting European operas in their original languages. By this time, Philadelphians could hear grand opera at several local venues on a fairly regular basis.

Americans generally looked to Europe for art music in this period, but in 1845 Philadelphia composer William Henry Fry (1811–64) and his brother Joseph (1812–65), a librettist, produced Leonora, the first true grand opera written by an American to be performed. Leonora premiered on June 4, 1845, at the Chestnut Street Theatre and had some fifteen subsequent performances in its initial run. It was produced several times at the Walnut Street Theatre in 1846 and a few times in New York in 1858, but eventually fell out of favor. William Henry Fry, who was also a journalist and music critic, was an outspoken advocate for American music at this time.

Academy of Music Opens, 1857

In the early 1850s local civic and cultural leaders began planning a new world-class opera house for Philadelphia. Construction began in 1855 on the American Academy of Music, as it was originally called, at the southwest corner of Broad and Locust Streets. Later shortened to Academy of Music, the building was modeled on the famed La Scala opera house in Milan, Italy, and when it opened on January 26, 1857, it was the largest and most ornate opera house in the city and one of the finest in the nation. Original plans for an opera training academy to be housed in the building were never realized. The first complete opera performance in the Academy of Music was Il Trovatore by Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) on February 25, 1857, an opera that had its American premiere at the Walnut Street Theatre the previous year. The Academy of Music immediately became the center of opera in Philadelphia, a distinction it never lost, and in the early twenty-first century remained the oldest continuously operating opera house in the United States.

As grand opera grew increasingly popular in the late nineteenth century, new opera houses were built throughout Philadelphia to accommodate the expanding audience. The Chestnut Street Theatre burned down again in 1855 and was replaced by a third theater of that name in 1863, built on the north side of Chestnut Street west of Twelfth Street. Two new opera houses were built in 1870: the Arch Street Opera House on the north side of Arch Street just west of Tenth Street and the Chestnut Street Opera House on the north side of Chestnut Street west of Tenth Street. (Both Arch and Chestnut streets had separate venues called “theatre” and “opera house” at this time.) During this period, additional opera houses opened as opera spread throughout the region. In West Chester, Pennsylvania, Horticultural Hall (built in 1848) became an opera house in 1869. In Wilmington, Delaware, the Masonic Hall and Grand Theater opened in 1871 as a venue for opera and other entertainment. (Later renamed the Grand Opera House, the theater reopened as a performance venue in the 1970s.)

In Philadelphia, North Broad Street became an important corridor for grand opera in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century with the construction of two major opera houses. In 1888 beer brewing magnate John Betz (1831–1908) built the Betz Germania Opera House at the southwest corner of Broad Street and Montgomery Avenue, and in 1908 opera impresario Oscar Hammerstein I (1846–1919) built the huge Philadelphia Opera House at the southwest corner of Broad and Poplar Streets. Both venues initially had resident opera companies, but neither company lasted very long. The Metropolitan Opera of New York City, which had been performing in Philadelphia since the 1880s, took over the Philadelphia Opera House, changed its name to the Metropolitan Opera House, and gave regular performances there from 1910 to 1920, after which it returned to the Academy of Music. In 1931 the Philadelphia Grand Opera Company gave the high-profile American premiere of the modern opera Wozzeck by Austrian composer Alan Berg (1885–1935) in the Metropolitan Opera House, with Philadelphia Orchestra music director Leopold Stokowski (1882–1977) conducting.

Theaters were also built for the various types of vernacular musical theater popular in Philadelphia from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century, such as minstrelsy, vaudeville, burlesque, and ethnic theater. While these “low brow” types of entertainment generally aimed for a different audience than grand opera, their venues were sometimes called “opera houses.” Sanford’s Opera House, later known as the Eleventh Street Opera House, located on the east side of Eleventh Street just below Market Street, was a popular minstrel hall in this period. Sometimes vaudeville houses hosted grand opera as well; the local vaudeville houses of national vaudeville impresario Benjamin Franklin Keith (1846–1914) hosted grand opera on occasion.

The Rise of Operetta

The late nineteenth century saw the rise of operetta, a lighter, simpler form of musical theater that aimed primarily to amuse (as opposed to the loftier aspirations of grand opera). Also known as light or comic opera, operetta occupied a place between grand opera and the more respectable forms of vernacular musical theater. The Operatic Society of Philadelphia, an amateur group that operated from 1906 to 1934, performed mostly operetta, although it also occasionally offered grand opera. The Savoy Company, founded in Philadelphia in 1901 to perform the English operettas of the famed composing team of librettist W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900), remained active in the early twenty-first century as the oldest amateur theater company in the world dedicated solely to Gilbert and Sullivan works.

A number of new Philadelphia grand opera companies formed in the early twentieth century, while outside companies maintained a presence in the city. The Metropolitan Opera of New York City continued its regular weekly performances in Philadelphia and the new Philadelphia Chicago Grand Opera Company split time between the two cities from 1910 to 1914. Both companies used the Metropolitan Opera House. Among the local opera companies established in the first decades of the twentieth century were three different ones called Philadelphia Grand Opera Company (operating at various times from 1916 to 1932), the Pennsylvania Grand Opera Company, Philadelphia Civic Opera Company, and Philadelphia La Scala Opera Company. Many were short-lived groups, lasting from one to six seasons before folding. They performed mostly in the Academy of Music, although some used the Metropolitan Opera House. Many ceased operations during the Great Depression of the 1930s. To fill the void left by their demise, the Philadelphia Orchestra offered a series of ten grand operas in the Academy of Music as part of its 1934–35 concert season.

The mid to late twentieth century was a period of consolidation for Philadelphia opera companies, as well as overall contraction of opera activity in the city. The Metropolitan Opera of New York City discontinued its regular Philadelphia appearances in 1961. Philadelphia La Scala Opera Company (1925–54) and Philadelphia Civic Grand Opera Company (1950-54) merged in 1954 to form the new Philadelphia Grand Opera Company. In 1975 Philadelphia Grand Opera Company merged with Philadelphia Lyric Opera Company (1958–74) to form Opera Company of Philadelphia. Most of these local companies were based in the Academy of Music (the Metropolitan Opera House had become largely inactive as a music venue by the late twentieth century), although another company, Pennsylvania Opera Theatre (1975–93), was based primarily in the Merriam Theatre on South Broad Street (originally built in 1918 as the Schubert Theatre to host Broadway shows) and in the early 1980s presented some operas in the former Arch Street Opera House, which had been renamed the Trocadero.

In 2013 the Opera Company of Philadelphia, the city’s only remaining grand opera company, changed its name to Opera Philadelphia. Based in the Academy of Music, Opera Philadelphia presented both traditional grand opera as well as new operatic works, some commissioned by the company. Curtis Opera Theatre, a program of the Curtis Institute of Music, Philadelphia’s world-renowned music conservatory, also presented grand opera in this period, continuing a Curtis tradition of public opera performance begun in 1929. Both the Curtis Institute and the Academy of Vocal Arts, a vocal training school founded in Philadelphia in 1934, served as premiere training grounds for opera singers in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Changing musical tastes and competition with other types of entertainment forced the majority of Philadelphia’s opera houses to close or be converted to other uses, musical or otherwise. Most were eventually demolished. By the early twenty-first century, only three remained: Academy of Music, Arch Street Opera House/Trocadero, and Metropolitan Opera House. Of these, only the Academy of Music was still an opera house.

From its beginnings in Philadelphia in the mid-eighteenth century, opera grew to be an important part of the city’s cultural life. Its popularity ebbed and flowed as tastes changed over time, but it remained a vital art form. In the early twenty-first century, Philadelphia audiences continued to avail themselves of performances from both the traditional opera repertoire as well as new works in the still evolving genre.

Jack McCarthy is a music historian who regularly writes, lectures, and gives walking tours on Philadelphia music history. A certified archivist, he directed a project for the Historical Society of Pennsylvania focused on the archival collections of the region’s many small historical repositories. He has served as consulting archivist for the Philadelphia Orchestra and the 2014 radio documentary Going Black: The Legacy of Philly Soul Radio and gave several presentations and helped produce the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s 2016 Philadelphia music series “Memories & Melodies.” (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Delaware Valley Opera Company brings Italian opera to Roxborough (WHYY, November 18, 2011)

- At national conference, local opera companies showcase new works (WHYY, June 12, 2012)

- Keeping watch over the flock at the old Metropolitan Opera House (WHYY, November 19, 2012)

- Fusing art with technology - an experiment in developing opera for the 21st Century (WHYY, October 2, 2014)

- Trenton soup kitchen artists embrace opera (WHYY, June 25, 2015)

- Opera Philadelphia's production of 'Yardbird' moves on to Harlem's Apollo (WHYY, December 9, 2015)

- 'Beyond Orientalism' to discuss Opera Philadelphia's modified 'Turandot' and its depictions of Asians (WHYY, September 26, 2016)

- 'Brilliant' debut of two Shakespearean operas in Delaware (WHYY, May 19, 2016)

- OperaDelaware’s Spring Festival has become a valuable tradition (WHYY, May 2, 2017)

- Restored to former glory, The Met opens on North Broad Street (WHYY, December 8, 2018)

Links

- Memories and Melodies: A Journey through Philadelphia's Musical Legacy (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- What Philadelphia neurologist founded The Savoy Company? (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Marian Anderson Historical Society — Keeping Opera Singer’s Music Alive (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Metropolitan Opera House — Oscar Hammerstein's Operatic Ambition in Philadelphia (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Marian Anderson Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Mario Lanza Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Metropolitan Opera House (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The Metropolitan Opera House Revisited (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Something New In America: Serious Opera, 1757 (Hidden City Philadelphia)