Public Transportation

By John Hepp | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

For more than three centuries public transportation has helped both to shape and define the Greater Philadelphia region. Befitting one of the world’s largest cities, Philadelphia and its hinterland have been served by a bewildering array of transportation options, and these vehicles and routes have helped to define the extent of the region.

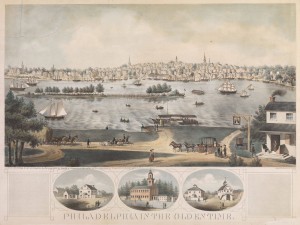

Public transportation – consisting of vehicles that operate on fixed routes used by the public – began in the region in 1688 with a ferry between Philadelphia and what is now Camden, New Jersey. This early line, though not a success, spawned additional ferry service and quickly established a Philadelphia hinterland in New Jersey. It was an early example of land outside Pennsylvania being tied economically and culturally to the city and established a precedent for southern New Jersey to develop in association with Philadelphia.

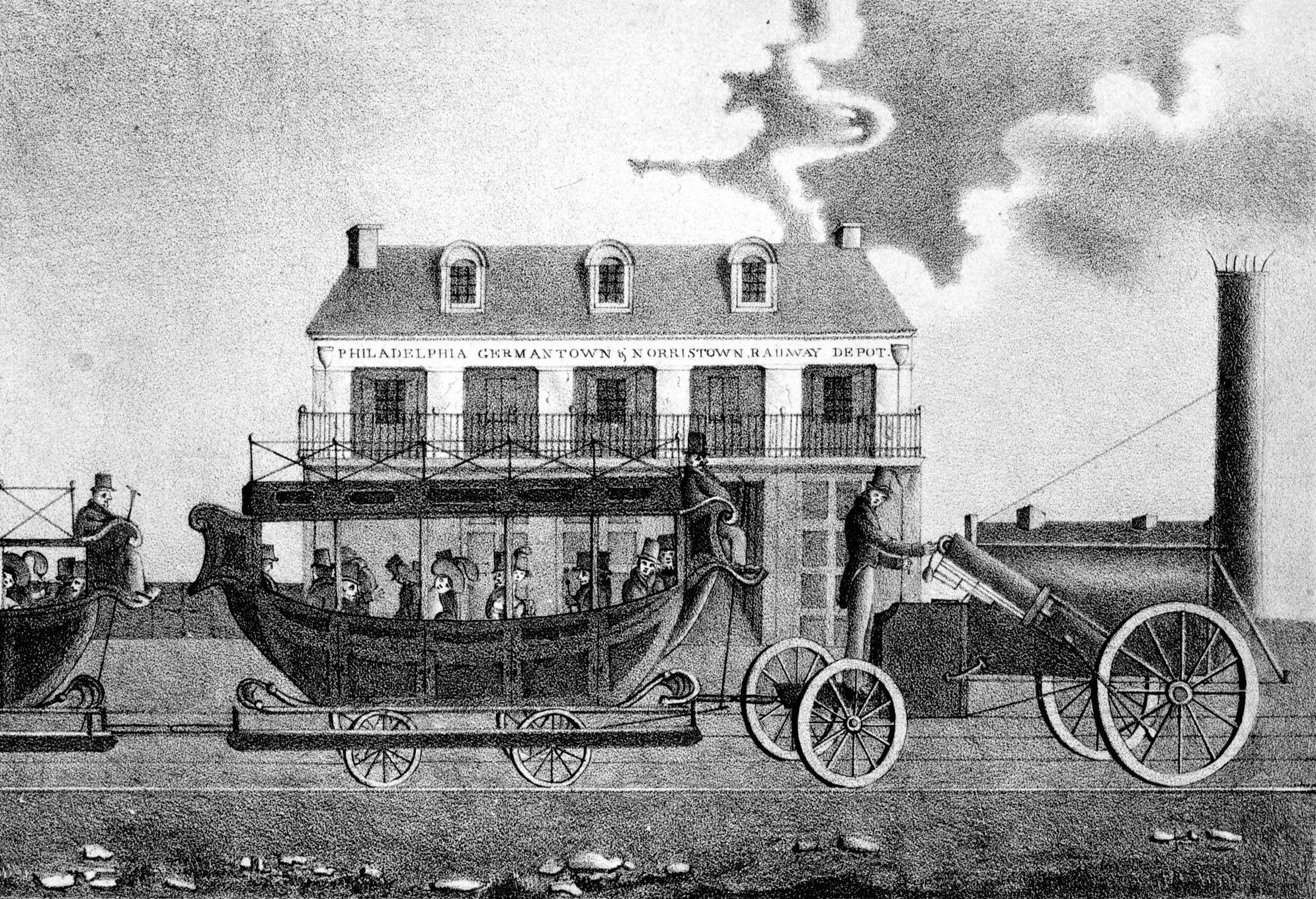

It would be more than one hundred years before local public transportation extended beyond ferries, but during the early nineteenth century an explosion of options developed as the city sought to expand both physically within the region and economically across the region and nation. In December 1831, Philadelphia ceased to be a walking city for those who could afford the fares of the new omnibus service in the city and its immediate suburbs in the county. The next year saw the introduction of commuter trains on the Philadelphia, Germantown & Norristown Rail Road, which allowed the middle classes and above to separate home from work not just within the city but also in portions of Philadelphia County like East Falls, Germantown, and Chestnut Hill, and in neighboring Montgomery County.

Not long after Philadelphia’s political consolidation in 1854, the streetcar, a technological change in public transportation, became the vehicle that allowed the city’s grid to expand throughout the once rural county. On January 20, 1858, the first streetcars in the region began to be operated by the Frankford and Southwark Philadelphia City Passenger Railway Company. These horse-drawn streetcars quickly replaced omnibuses as the streetcars were larger, quicker, and more profitable. Soon the streetcars extended throughout the region to areas previously poorly served by public transportation. Coupled with an expansion in commuter rail service, Philadelphia could justly claim one of the finest transportation systems in country by the time of the nation’s Centennial Exhibition in 1876.

Network of Streetcars and Trains

By the 1880s, middle-class Philadelphians had a more-than-adequate system of horse-drawn streetcars and steam-hauled commuter trains to serve their transportation needs in both the booming metropolis and its expanding hinterland in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. The lines of privately-owned streetcar companies occupied every major (and many minor) streets in Center City and extended southward, westward, and northward from the original urban core along the Delaware River into the adjoining neighborhoods. In addition to these routes centered on the business district, a large number of local lines operated in the other densely populated portions of the city like West Philadelphia.

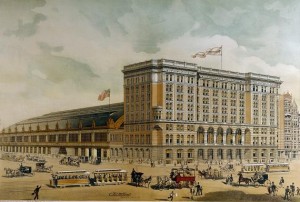

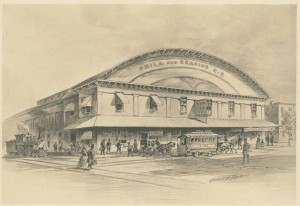

Commuter trains served not only the city but also the larger region. The 1870s and 1880s were a period of transition for the railroads; some lines had quite intensive service while others still had surprisingly few trains. Overall, however, the steam trains were not used by many middle-class Philadelphians for their daily commute in 1880 simply because all of the downtown termini were a long walk or streetcar ride from the business district. By 1893, all three rail systems serving the city relocated their main facilities to Center City, and the daily commute by steam train became more viable for those who could afford the fares. The electric trolley, introduced in the mid-1890s after a brief and unsuccessful flirtation with cable cars, quickly became the typical mode of middle-class transport and eventually served as a symbol of the late-nineteenth century. In just five years, from 1892 to 1897, trolleys replaced all the horse-drawn streetcars and cable cars in the city.

In addition to a reasonably well-to-do ridership, all forms of public transportation in the region had comparatively low entry costs and only moderate regulation, and, through the 1860s, this meant that most providers were small, specialized organizations with just one or a few routes. Railroad and streetcar companies tended to go where their names claimed and not elsewhere. For example, a potential passenger knew the ultimate destination of a West Chester & Philadelphia train. Following the Civil War, however, a period of intense competition between long-distance railroads (such as Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Railroad) brought about consolidation in the railway industry nationally in the 1870s and 1880s. Technological changes, such as cable cars and electric trolleys at approximately the same time, encouraged similar mergers in the streetcar industry. The result was a dramatic transformation from a competitive environment in the 1860s of many small companies to a monopoly streetcar company in the city, known by 1902 as the Philadelphia Rapid Transit (PRT), and only two railroad systems – the Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia & Reading. Combined, by 1900 these two companies provided virtually all passenger rail services for a region that stretched from the Jersey Shore to Harrisburg.

A combination of events in the 1890s began the shift from nineteenth-century public transportation, serving primarily the middle classes and above, to twentieth-century mass transportation aimed at moving as many people as possible. Some of the changes were largely technological: the development of subways and elevated railways and electric streetcars allowed for lower fares. Coupled with these technological changes often were political changes. New franchise agreements allowed for increased government regulation at a time when both politicians and civic boosters envisioned a New Philadelphia in which working-class Philadelphians could live at greater distances from their work. Other changes were economic with political ramifications. Although the organizers of the new monopoly traction company in Philadelphia became quite wealthy, service deteriorated and strikes increased, creating a political consensus that more government planning and regulation was needed in public transportation. The most important change, however, was that rising working-class wages, together with falling or static fares, allowed more people to ride the trolleys and subways more often for work, shopping, and pleasure.

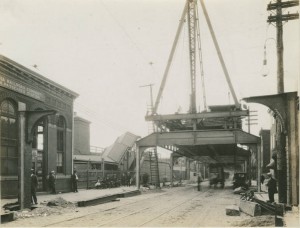

Market Street Subway-Elevated

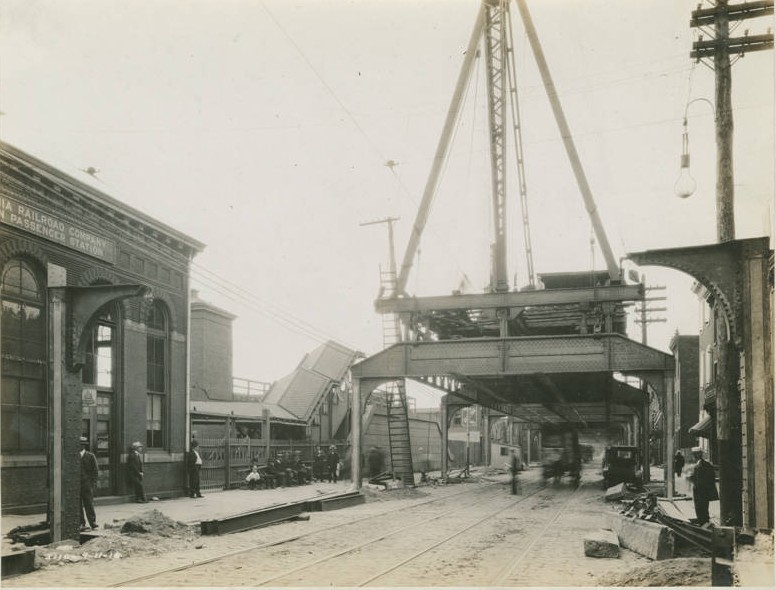

Technological change continued in the early twentieth century. The Market Street Subway-Elevated opened between 1905 and 1908, offering the city its first rapid transit line which, when coupled with suburban trolleys, gave the region its first affordable high-speed system. Because of the financial weakness of the private company that instituted the line, the city took the lead in subway-elevated development over the next few decades, extending the original line to Frankford in 1922 and opening the Broad Street Subway in sections between 1928 and 1932. Although the trolleys and the subway-elevated caused the commuter railroads to lose some riders, the two major companies embarked on an electrification program of their own and between 1906 and 1933 modernized major portions of their commuter rail network.

Another late-nineteenth-century invention, the internal combustion engine, had the greatest effect on public transportation in the region in the twentieth century. By the 1910s, motorized buses began to operate on the streets of the Philadelphia area. The PRT and other transit companies on both sides of the Delaware River initially used buses to supplement trolley routes but by the 1920s, began use buses to replace streetcars. Buses offered transit companies two advantages. First was more operating flexibility, as a bus could detour around an obstacle that would delay a trolley. The other was lower capital costs as buses operated on public highways while trolleys needed privately maintained rails.

In addition to the buses operated by the established, regulated transit companies, a new form of public transportation came to the region: the jitney. Jitneys were unregulated buses operated by private individuals, usually in competition with existing transit companies. The jitneys usually charged lower fares but often only operated during peak hours and on peak routes when they could be assured of heavy ridership. Although jitneys could be found throughout the metropolis, they were extremely popular in New Jersey, perhaps because that state had a particularly good public highway system.

Despite the advent of the automobile, for the first third of the twentieth century most residential development still followed the railroad and trolley lines. Even for the Philadelphians who could afford an automobile, the car remained more of a toy for weekend exploration than a family’s primary means of transport until midcentury.

Depression Hurts Public Transit

The Great Depression had many negative effects on the public transportation of the region. Both railroad systems cut back on their commuter services, and their lines in southern New Jersey to the shore – once fiercely competitive – were merged to create the Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines. Many small suburban trolley lines were abandoned, and other larger systems converted the electric streetcars to buses. In Philadelphia, the PRT declared bankruptcy and emerged in 1940 as the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC). The city’s ambitious rapid transit construction program slowed and then stopped.

Although public transportation ridership rose greatly during World War II, this increase was temporary. At the end of the war, automobile ownership increased and middle-class families left the older sections of the city for the car-friendly Great Northeast and suburbs. By the 1950s, the PTC was owned by National City Lines, a bus-friendly company that continued abandoning streetcar lines, and both the Pennsylvania and Reading railroads were cutting commuter service in response to growing losses.

In reaction to these declines in service, local and state governments became increasingly involved in public transportation starting in the late 1950s. In 1960, the City of Philadelphia began subsidizing service and purchasing equipment for use on commuter rail lines in the city to Chestnut Hill and Manayunk. The South Eastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) began to coordinate and fund all public transportation in Philadelphia and the Pennsylvania suburbs in 1965. SEPTA bought new equipment and built the Center City Commuter Connection in 1984 to link the former Pennsylvania and Reading systems. Similar changes happened in New Jersey, where the state initially funded train and bus services and later took over their operation. Perhaps the region’s most significant change at this time was the construction of the Lindenwold High Speed Line in New Jersey by the Delaware River Port Authority (DRPA). This line opened in 1969 and featured air-conditioned and computer-operated trains. More recently, New Jersey Transit opened the River Line between Trenton and Camden in 2004 and ridership has been well ahead of estimates.

Hubs and Spokes

By the first decades of the twenty-first century, public transportation in the Greater Philadelphia region centered on a few hubs (Trenton and Camden in New Jersey; Wilmington in Delaware; Chester, Norristown and Upper Darby in Pennsylvania; and Center City for the region) with spokes extending throughout the city, suburbs, exurban towns, and countryside. Along these spokes rows of working- and middle-class homes attested to public transportation’s role in shaping the region, and retail and commercial districts remained around lesser transit hubs like Frankford and Upper Darby. Because of its extensive public transportation system, Philadelphia had a lower than average car ownership rate for an American city. “Reverse commuting,” boarding a train or bus in the city to a job in the suburbs, also became increasingly common and new transportation hubs, like Plymouth Meeting and King of Prussia, continued to develop.

Public transportation faces a wide range of challenges from uncertain funding to the need to serve jobs in the suburbs with new hubs and routes. The four major public transportation providers in the region — SEPTA, DRPA, New Jersey Transit and DART First State—will have to adapt to these changes as the region’s transportation needs continue to evolve, as did their predecessors for more than three hundred years.

John Hepp is associate professor of history and co-chair of the Division of Global History and Languages at Wilkes University in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, and he teaches American urban and cultural history with an emphasis on the period 1800 to 1940. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- SEPTA taps hard-won $2.4B transportation funding for first project (WHYY, January 24, 2014)

- SEPTA running weekend service this summer on El, Broad Street Line (WHYY, June 3, 2014)

- Broad Street subway service for night owls begins (WHYY, June 13, 2014)

- No deal: SEPTA Regional Rail workers announce strike (WHYY, June 14, 2014)

- Obama intervenes in SEPTA strike: Service restored by Sunday morning (WHYY, June 14, 2014)

- Drivers, bikers in Philly have the edge on public transit passengers, pedestrians (WHYY, July 11, 2014)

- Students left on corner as Philly district reduces busing service (WHYY, August 18, 2014)

- Turns out a SEPTA predecessor used double-decker buses (WHYY, August 24, 2015)

- Jarrett Walker's philosophy of public transit as means to freedom (WHYY, December 7, 2016)

- SEPTA pulls 40 Market Frankford railcars after cracks discovered (WHYY, February 5, 2017)

- SEPTA transit fares to go up starting July 1st (WHYY, March 17, 2017)

Links

- Advertisement, Philadelphia, Germantown, and Norristown (Hagley Digital Images)

- All Aboard for Philadelphia! (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- The Rise and Fall of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company (Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Fondly, Pennsylvania)

- Chrostwait's Pennsylvania Municipal Law Reporter, Philadelphia Jitney Association, et al. v. Blankenburg, et al. (Google Books)