Textile Manufacturing and Textile Workers

Essay

Textile manufacturing began in Philadelphia soon after the city’s founding in 1682 and grew to be one of its chief industries. By the turn of the twentieth century Philadelphia was one of the world’s greatest textile manufacturing centers, with tens of thousands of workers making a wide range of products. The industry declined dramatically in the late twentieth century, part of a broader deindustrialization of the Philadelphia region at that time.

As early as 1690 three woolen weavers were working in Philadelphia, and in 1691 William Penn (1644–1718) wrote of “very good German linen” being made in Germantown. By the mid-eighteenth century, Philadelphia textile workers were making a variety of products. Andrew Burnaby, an Englishman who visited the city in 1759–60, noted the high quality of thread stockings made in Germantown, that Philadelphia’s Irish settlers made very good linens, and that some wool products had been fabricated in the city. While textile manufacturing increased as Philadelphia’s population grew, it was carried out mostly on a small scale—spinning, weaving, and knitting done primarily by hand in homes and small shops in the colonial period.

The late eighteenth century saw the first attempts at machine-based textile production in factory settings. The April 1775 issue of the Pennsylvania Magazine featured a drawing of a new “Machine for spinning twenty-four threads of cotton or wool at one time.” The magazine noted that the machine, built in Philadelphia by Christopher Tully, was the first one made in America. The United Company of Philadelphia for Promoting American Manufactures, established in 1775, used Tully’s machine in a factory it set up at Ninth and Market Streets and also employed some four hundred local women in hand spinning and weaving. The company’s initiatives were part of an effort by colonial leaders to spur domestic manufacturing in order to compete with England militarily and economically. The United Company ceased operations when the British occupied Philadelphia in September 1777 during the Revolutionary War. One of the members of the company was Samuel Wetherill (1736–1816), an early Philadelphia industrialist who carried on a substantial textile manufacturing business and was a major supplier to the Continental Army. Wetherill later focused on manufacturing chemicals and paint and founded a family-run paint and varnish company that remained in business in Philadelphia into the twentieth century.

Surreptitiously Imported Technology

After the war, Wetherill was active in another Philadelphia organization that sought to undertake large-scale textile manufacturing, the Pennsylvania Society for the Encouragement of Arts and Domestic Manufactures, established in 1787. The society’s chief spokesman was Philadelphia merchant and economist Tench Coxe (1755-1824), an influential advocate for the development of American manufacturing. The society set up a textile factory in 1788 in the same building the United Company had used, but the factory was destroyed by fire in 1790 and not rebuilt. In 1791, Philadelphia merchant William Pollard (d. 1801), an English immigrant, was awarded the first U.S. patent for a machine for “Spinning and Roving Cotton.” His attempt to set up cotton factories in the city was thwarted by the business failures of his financial backers, however. Much of the technology for these initiatives was imported surreptitiously from England, where the Industrial Revolution was already well underway, but where government authorities, in an effort to protect England’s industries from competition, enforced strict rules against machines or workers with mechanical expertise leaving the country.

New England was the early leader in the industrialization of the American textile industry in this period. English immigrant Samuel Slater (1768–1835) established the nation’s first successful textile mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, in 1793, using mechanical expertise he had secretly brought to America from England. Slater developed the “factory system” of textile production in the United States, a system that a group of Massachusetts businessmen adapted and expanded in the early nineteenth century with huge factories in Waltham, Lowell, Fall River, and other parts of the state. Unlike the later textile mills of Philadelphia, which were generally smaller and specialized in a particular type of work, the New England mills were large, fully integrated operations that mass-produced materials and housed all aspects of the manufacturing process.

While eighteenth-century attempts at large-scale mechanized textile manufacturing in Philadelphia were largely unsuccessful, textile mills proliferated in the region in the early nineteenth century. England’s restrictions on the transfer of technology to America were increasingly circumvented, and numerous European immigrants with expertise in textile production settled in the region and set up factories. The invention of the cotton gin in Georgia in 1793 made possible the processing of enormous amounts of raw southern cotton for shipment to Philadelphia mills, while the introduction of steam power and rail transportation in the 1820s and 1830s spurred further expansion of the local textile industry. Industrial communities such as Manayunk and Frankford, which had developed on the strength of their early water-powered mills, became major textile centers in the antebellum period, joining Germantown, which had long been a locus of the hand-frame knitting industry, and the emerging industrial powerhouse of Kensington.

Other textile centers developed throughout the greater Delaware Valley region as well. In the early 1830s the Trenton Delaware Falls Company built a canal in Trenton, New Jersey, to provide water power for a number of that city’s textile mills. In Wilmington, Delaware, in 1831, Joseph Bancroft (1803–74) established Bancroft Mills, which grew to be one of the nation’s largest textile manufacturers. Textile mills operated throughout the region in the early nineteenth century, particularly in towns that grew up along rivers and creeks, where water power fueled industries until the introduction of steam engines in the 1820s and 1830s.

Machinery Propels Textile Industry

The United States at this time was in the midst of the Industrial Revolution. Philadelphia was a key leader in this development, emerging as one of the most highly industrialized cities in the world, with textile manufacture as one its largest industries. An important group of mechanical engineers and inventors developed new manufacturing technologies in a number of industries in this period, particularly in textiles. While hand weaving and home-based textile production continued, machine-based manufacturing in mills became the foundation of Philadelphia’s rapidly expanding textile industry. By the Civil War the city was one the nation’s premier textile centers.

The mechanization of textile manufacture gave rise to serious labor issues. Work that had previously been done by hand in homes and shops was now centralized and automated in large mills that employed hundreds or thousands, such as those of William Logan Fisher (1781-1862) in Germantown and Joseph Ripka (1789-1864) in Manayunk. Both men and women comprised the workforces in these mills; women had always played a significant role in textile production. Working conditions in the mills were often miserable. Employees worked twelve- or fourteen-hour days, six days a week, doing monotonous tasks in unhealthy conditions for low pay. Strikes and other labor actions were common, as were aggressive, sometimes violent responses by mill owners. Child labor was another major issue. Children made up a considerable percentage of the textile workforce and were also subjected to terrible working conditions. There were also conflicts between factories and Philadelphia’s many independent handloom operators, who viewed mechanization as a threat to their livelihood. In the 1830s a group of Kensington handloom weavers tried to burn down a Manayunk mill that had installed new labor-saving machinery.

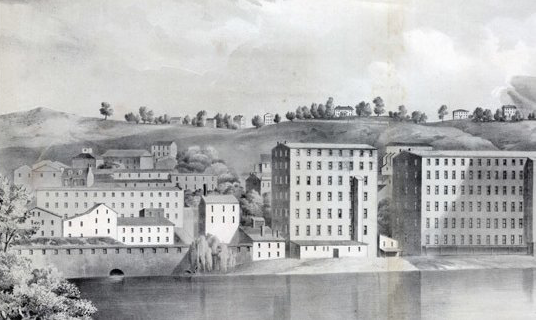

Labor issues notwithstanding, the mid-nineteenth century saw tremendous growth in Philadelphia’s textile industry. This gave rise to a number of local textile family dynasties: the Fisher family with factories in Germantown; the Campbell, Schofield, and Dobson families in East Falls and Manayunk; Ripka’s extended family in Manayunk and along the Pennypack Creek in Northeast Philadelphia; the Bromleys in Kensington and Frankford; the Dolans in North Philadelphia; and others. As titans of the local textile industry, many of these families became part of Philadelphia’s social elite, taking active roles in city business and political affairs. Some of them suffered significantly during the Civil War, when their connections with southern cotton growers were severed by the conflict. While most survived, one who did not was Joseph Ripka, who closed his Manayunk cotton mills during the war and died in 1864.

In 1850, Philadelphia had approximately twelve thousand textile workers. By 1882, it had over sixty thousand, employed by nearly one thousand different firms. Many of these workers were low-skilled immigrants, particularly Irish Catholics who settled in Kensington in large numbers in the mid-nineteenth century and made up a significant percentage of that neighborhood’s mill workers. Religious tensions between Kensington’s Catholic and Protestant textile workers led to Philadelphia’s deadly 1844 nativist riots.

The Appeal of Specialty Companies

While the city had its share of large mills that employed thousands of workers, the real strength of its textile industry was its many small to midsize specialty firms. Textile products made in Philadelphia often went through a multi-site process in which different companies did different types of work. Textile fibers were spun in one factory, woven in another, dyed in a third, and finished in a final one. This interconnected network of smaller, specialized textile firms was a defining characteristic of Philadelphia’s textile industry in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

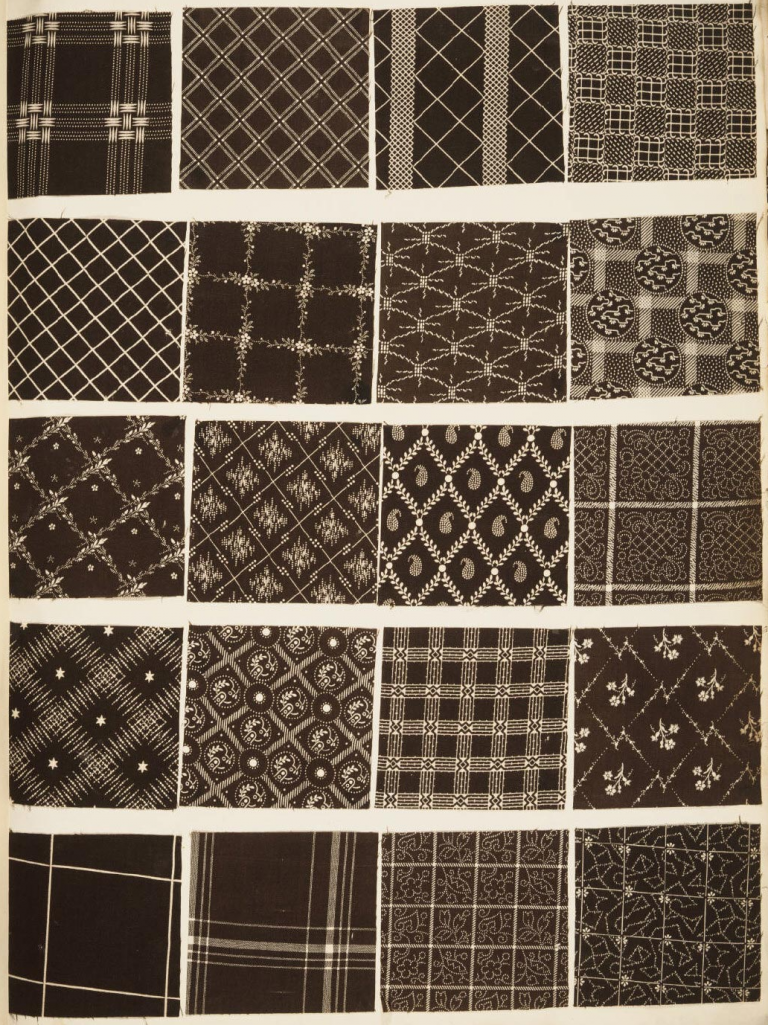

Another key aspect of Philadelphia’s textile industry was the great variety of products it generated. Whereas other major American textile centers usually focused on a single product, Philadelphia’s textile sector produced a wide range of materials. The 1912 book Manufacturing in Philadelphia, 1683–1912, listed among the city’s textile products carpets, cordage, jute, linen goods, nets and seines, cotton goods including small cotton wares, hosiery and knit goods, shoddy (a recycled wool product), silk fabrics, woolen and worsted products, wool pulling and wool scouring, felt goods, wool hats, and fur felt hats.

Of the many areas of the city where these products were made, the largest by far was Kensington, the sprawling industrial neighborhood to the northeast of Center City. Home to hundreds of textile mills, large and small, and a vast, primarily immigrant workforce, Kensington boasted one of the greatest concentrations of textile activity in the world. By 1910 there were four hundred textile firms employing thirty thousand workers in Kensington. Manufacturing in Philadelphia, 1683–1912, noted that from the tower of the Bromley Mill in Kensington there were more textile mills within the range of vision than in any other city in the world.

Labor strife continued in Philadelphia’s textile industry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as mill owners periodically cut wages or work hours in response to changing economic conditions and workers responded with strikes and other actions. The Knights of Labor, which began in Philadelphia in 1869 as a secret society of city garment workers and grew into a huge nationwide labor organization, organized several strikes in Philadelphia in the late nineteenth century. There were major strikes in the early years of the twenty-first century as well, including particularly large strikes in 1903 and 1910. The shifting dynamics of power between labor and management was a key factor shaping Philadelphia’s textile industry in this period.

In 1900, a City of Firsts

This was the heyday of textile manufacturing in Philadelphia. The city was first in the nation in 1900 in total value of products in several textile categories: hosiery and knit goods, carpets and rugs, dyeing and finishing, upholstery materials, and recycled wool. In 1909 this value reached $153 million, greater than any city in the world and more than double that of any other American city. Longtime Philadelphia family textile dynasties such as Dobson and Bromley employed thousands of workers, while hundreds of smaller companies provided specialty services. The Great Depression of the 1930s curtailed the industry significantly and led to the decline of some of the city’s major textile companies, but many survived and several important new ones were established.

While traditional textile manufacturing continued in Philadelphia, firms elsewhere in the region developed new types of materials in the early twentieth century. In 1908 immigrant English businessman Samuel Agar Salvage (1876–1946) founded the American Viscose Corporation to make rayon, a type of artificial silk. In 1911 he built a large plant in Marcus Hook, Delaware County, to make the product. He also built a planned English-style worker community, known as Viscose Village, for his employees. In Wilmington, Delaware, the DuPont Company transformed the textile industry with the introduction of synthetic fibers in the 1930s and 1940s. DuPont-developed products such nylon, Orlon, and later Dacron revolutionized how textiles were made and used in the mid-twentieth century. Some of these products were manufactured in DuPont plants in Delaware, but many were made in company plants in other parts of the nation.

Philadelphia’s textile industry remained strong through the mid-twentieth century, but, like much of the city’s industrial sector, it declined significantly in the post–World War II period. A number of economic and social factors—cheaper labor and energy costs in other parts of the nation or world, competition from producers of lower-cost products, changing urban demographics—led to most Philadelphia textile factories closing or moving out of the city in the latter part of the century. Some stayed local, however; scores of mills transferred operations to surrounding counties, especially in expanding areas of South Jersey.

By the early twenty-first century, Philadelphia’s textile industry was comprised of mostly small niche firms making specialized products for well-defined markets. While overall, the sector operated on a fraction of its massive early twentieth-century scale, about 150 textile manufacturers operated in the city in the mid-2010s. These included firms such as Ehmke Manufacturing Company in Juniata, which made fabric products for the defense industry; Boathouse Sports, also in Juniata, maker of specialized sports apparel; Grip-Flex Corporation in Port Richmond, which made braided cords and uniform trimmings; and Humphrys Textile Products in Kingsessing, makers of industrial tarps and canvas. These and other local companies continued Philadelphia’s longstanding textile manufacturing tradition, a tradition that dated to the late seventeenth century and brought the city international recognition as one of the greatest manufacturing centers in the world.

Jack McCarthy is an archivist and historian who specializes in three areas of Philadelphia history: music, business and industry, and Northeast Philadelphia. He regularly writes, lectures, and gives tours on these subjects. His book In the Cradle of Industry and Liberty: A History of Manufacturing in Philadelphia was published in 2016 and he curated the 2017–18 exhibit Risk & Reward: Entrepreneurship and the Making of Philadelphia for the Abraham Lincoln Foundation of the Union League of Philadelphia. He serves as consulting archivist for the Philadelphia Orchestra and Mann Music Center and from 2011–16 directed a major archival project for the Historical Society of Pennsylvania focusing on the collections of the region’s many small historical repositories. (Author information correct at time of publication.)

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Andrew Burnaby's Travels Through North America (Library of Congress)

- Fabric Row (PhilaPlace)

- Fabric Sample Book - David S. Brown and Company (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Mary Harris "Mother" Jones Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory)

- Mother Jones and the Fight Against Child Labor in Kensington's Textile Mills (Philadelphia History Blog)

- Petition of William Pollard to the Patent Board, 1790 (National Archives)

- Samuel Wetherill Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory)

- Walter Licht Speaks on Philadelphia's Textile Heritage (Mural Arts Philadelphia)