Typhoid Fever and Filtered Water

Essay

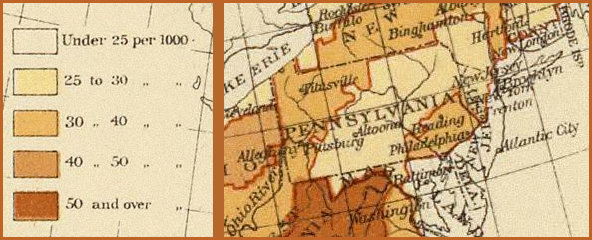

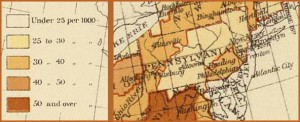

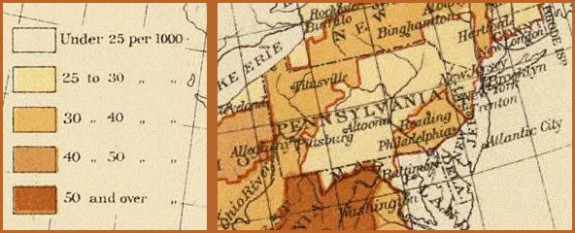

Philadelphia in the late nineteenth century stood shamefully high among large American cities in rates of death from typhoid fever (also known as enteric fever). Caused by a type of Salmonella bacterium, the disease had become common in Philadelphia and other cities with crowded populations, inadequate disposal of human waste, and lack of water treatment. Local outbreaks and the knowledge that they might be prevented by improving the water supply spurred physicians, activists, and organizations to press Philadelphia’s city government to improve water quality with a filtering system. After a decade of delay and fumbling, a massive apparatus installed between 1900 and 1910 largely ended deaths from typhoid fever.

By the last decades of the nineteenth century, the Philadelphia region no longer suffered from massive epidemics of yellow fever, cholera, or smallpox—though the horrific influenza pandemic of 1918 lay in the future. Typhoid fever, meanwhile, had become both endemic (common) and given to outbreaks or local epidemics. Philadelphia endured outbreaks in 1876 (probably relating to the crowds coming to the city for the Centennial Exhibition), 1888-1889, 1899, and 1906–but the disease was always present. During the 1890s, more than 5,400 deaths from typhoid fever occurred. More died from tuberculosis, but the means existed to prevent typhoid. The symptoms of typhoid include high fever, headaches, a subtle rash, vomiting, and sometimes diarrhea; complications such as bowel perforation or hemorrhage can cause death. The microbe spreads through the “fecal-oral” route, meaning contaminated milk, asymptomatic carriers, and most importantly, impure water. Before antibiotics, treatment consisted of a “mild” diet (milk, eggs, beef broth), bed rest, and cold baths, the last much loathed by patients. Surgery could occasionally save patients who had bowel perforations.

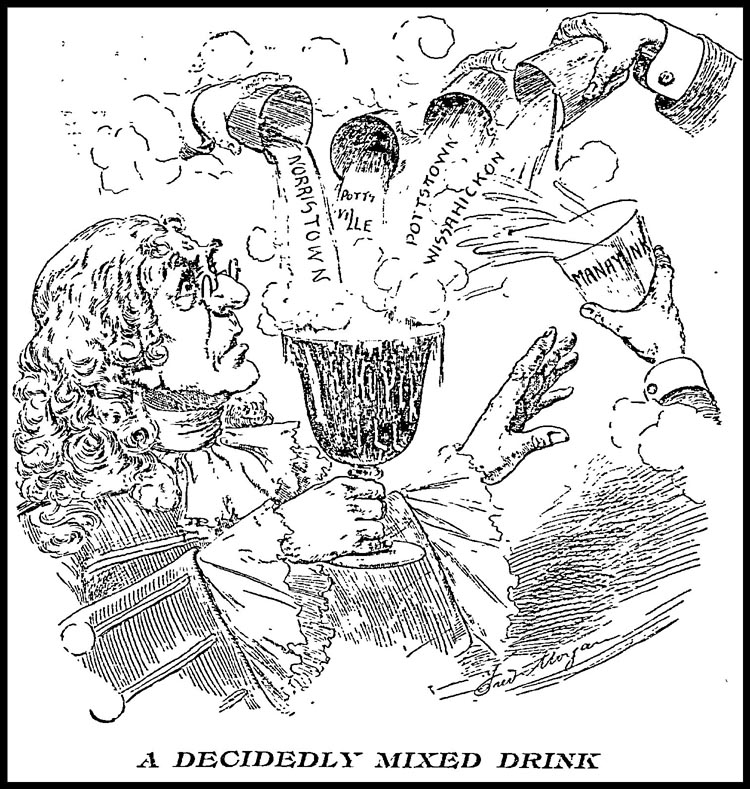

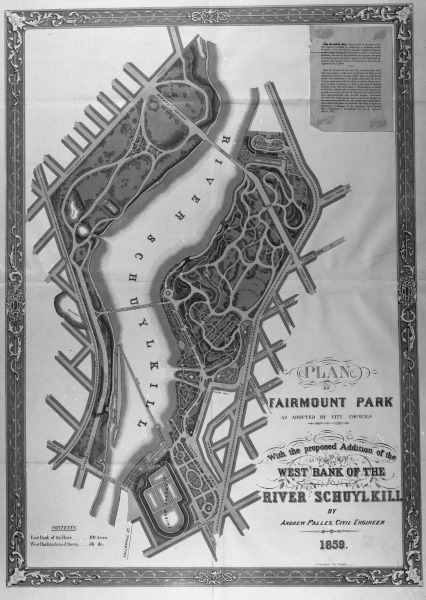

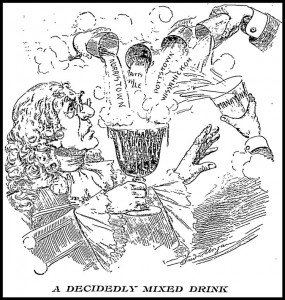

In a time of industrial growth and population increase, typhoid was a regional problem, but no regional framework existed to deal with it. In the nineteenth century, as in the twenty-first, Philadelphia drew its water from the Schuylkill and the Delaware Rivers, into which both the city and upstream districts discharged all manner of industrial and human waste. The creation of Fairmount Park in the nineteenth century lessened the city’s contribution to the Schuylkill’s considerable defilement. But Manayunk within the city and upstream industrial towns such as Norristown, Pottstown, and Reading created pollution “as diversified as the occupation of the people: sewerage, chemical, wool-washing, dye stuff, butcher and brewery refuse–there is almost nothing lacking,” according to the 1883 Annual Report of the Philadelphia Bureau of Water. In addition to the ills and pollution caused by industrial waste, matter added by latrines and flush toilets could disseminate typhoid. A similar situation, though perhaps less dire, befouled the Delaware.

Larger Reservoirs

As one response to this menace, in the 1880s the Bureau of Water built an “interceptor sewer,” a sort of bypass channel that drained waste from Roxborough, Manayunk, and Falls of Schuylkill (East Falls), diverting it from the river. The city also created larger reservoirs to allow water more time to settle, so that gravity could lead to sedimentation of particulate contamination. The rate of deaths from typhoid declined into the early 1890s, but still amounted to a persistent loss of life of young and old Philadelphians, which was generally recognized as preventable. More seemed to be needed. In 1889, influential Germantown physician and author Henry Hartshorne (1823-97) argued for filtration of the water supply in a pamphlet titled Our Water Supply: What it is and What it Should Be, published on behalf of a committee of citizens. Hartshorne cited recent experience in Europe, where cleansing of municipal water through “slow” filters of layers of sand and crushed coal had become an accepted technique. The method had recently been introduced into the United States and became more widely known through an important book published in 1895, The Filtration of Public Water-Supplies, by engineer Allen Hazen (1869-1930).

Into the 1890s, a variety of lay and medical groups in Philadelphia campaigned for clean water and particularly for a system of filters. These included the Women’s Health Protective Association (founded in 1893), the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the Civic Club, and beginning in 1896 a broadly-based Citizens’ Organizations Filtration Committee. The City Councils (then bicameral) took up the issue, but political factionalism, unclear authority to borrow large funds, and an extreme diversity of opinion delayed approval of funding. For example, while some members of Council favored filtration, Thomas Meehan (1826-1901), the “dean of American horticulturists” and a locally prominent Germantown resident, dismissed its value and may have doubted the germ theory of infectious disease. In addition, the chief of the Bureau of Water, a capable engineer named John Cresson Trautwine (1850-1924), deplored the waste of water more than the waste in it, and so persistently urged the metering of water (then not in effect) more than the filtering of it. In addition, several proposals to bring pure water from either the Pine Barrens of New Jersey (suggested in 1891) or from unpolluted realms of the upper Schuylkill (1889, 1897) episodically competed for attention.

A particularly vicious outbreak in 1898-99 (which some alleged related to the movement of soldiers into the city at the time of the Spanish-American War) resulted in 948 deaths in 1899 and finally provoked progress. The City Councils approved the request of Mayor Samuel Ashbridge (1849?-1906) for a $12 million bond issue to build the system of sand filter beds. Construction began in 1901 and 1902 at the reservoirs and pump stations in Roxborough (“upper” and “lower”), West Philadelphia (Belmont), and Torresdale. The end of the decade saw the last filter beds completed, at the Queen Lane location. Numerous photographs made by the city show the enormity of these vast undertakings, probably then the largest municipal projects in Philadelphia’s history. The plan included laying massive pipes interconnecting the several water facilities. The entire effort ended up costing an estimated $26 million to $28 million.

Typhoid Declines

Typhoid fever rates eventually fell by more than 90 percent with the advent of filtered drinking water–which was also, at least sometimes, clear and free of odor, something new to Philadelphians. A serious outbreak occurred in 1906, but it was mainly limited to areas not yet receiving filtered water. In 1909 chlorination was added to further combat water-borne bacteria. In the 1910s and 1920s typhoid immunization came into wide use. Occasional small epidemics still occurred; one in 1911 resulted from a rupture of a large main supplying the Roxborough plant. Until immunization made most of the population resistant to the disease, some outbreaks could be traced to a picnic mishap or other tainted food. Into the 1920s and 1930s, the city’s public health officials rightly or wrongly deemed most cases to have been acquired outside the city, particularly at the New Jersey shore during the summer. Enough cases continued to occur, however, to induce the closing of the popular springs throughout Fairmount Park, though these likely did not spread typhoid to any great extent. By 1935, rarely did a Philadelphian die from typhoid fever.

Steven J. Peitzman is Professor of Medicine at Drexel University College of Medicine. His historical work includes the book A New and Untried Course: Woman’s Medical College and Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1850 – 1998 (Rutgers University Press, 2000) and articles about medicine and medical education in Philadelphia and Germantown. He also has published on the history of his clinical area, kidney disease. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- PhilaPlace: The Fairmount Water Works — Disease and the City’s Water Supply (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Watershed History: Roxborough Water Works (Philadelphia Water Department)

- https://water.phila.gov/blog/watershed-history-roxborough-pumping-station-demolition

- Shawmont Pumping Station Razed (Hidden City Philadelphia)