U.S. Congress (1790-1800)

Essay

During the 1790s, while Philadelphia served as the nation’s temporary capital, the U.S. Congress met problems and threats to the nation that tested the endurance of the Constitution and the republic it framed. Domestic issues of finance, taxation, sectionalism, Indian affairs, and slavery divided the delegates into bitter political camps, and international relations fomented disagreements as well. Partisan politics aside, Congress during this decade forged a government that remained intact, despite expectations to the contrary from the prevailing monarchies overseas.

Many of the members in Congress during the 1790s knew Philadelphia well. The Continental and Confederation congresses had met in the State House from 1775 through 1783, and dozens who had served, including some of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and Constitution, were elected to the First Congress. Delegates to Congress now operated under a new frame of government, with different political realities. They worked with a sense that they were setting precedent for future legislators.

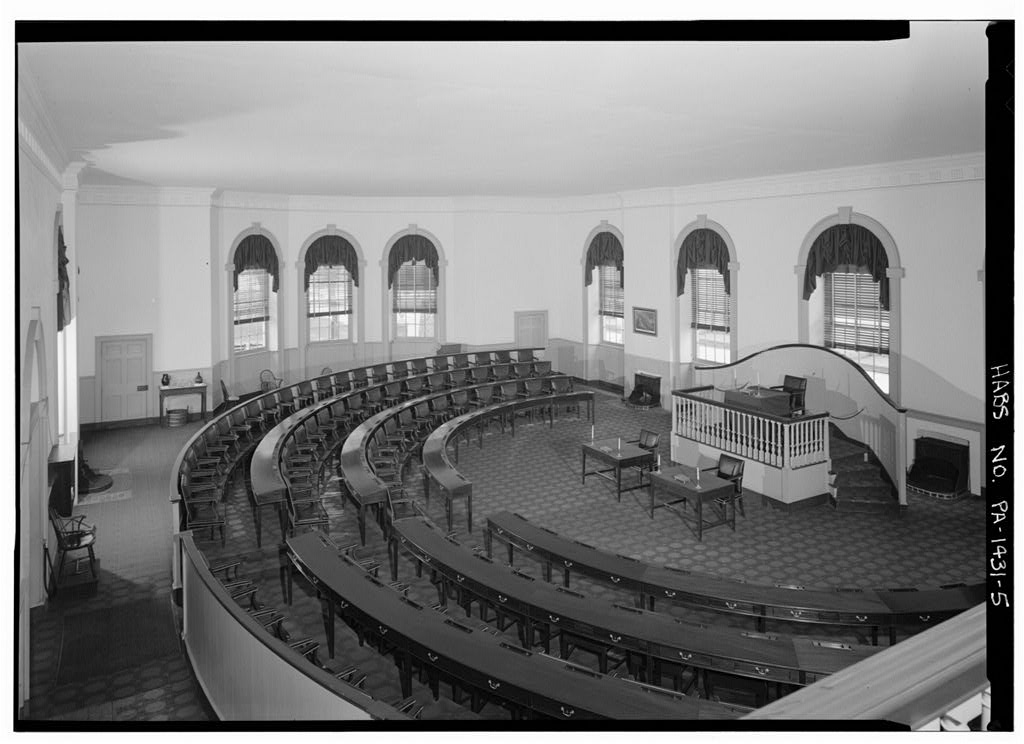

Congress opened its first Philadelphia session in December 1790, after the newly constructed (1787) county courthouse at the corner of Sixth and Chestnut Streets had been renovated to accommodate them. The House of Representatives met in the large first-floor room and the senators met above in the second floor’s southern room, with offices and committee rooms filling the second floor’s northern end. Next door, the Pennsylvania Assembly and governor (provincial executive) worked in the State House, today’s Independence Hall, while the mayor and his court occupied City Hall (1791) on the Fifth Street end. It was a unique time when all three levels of government sat on the State House Square together.

Boomtime in the New Capital

Philadelphia raced to meet the demands of the enormous influx of people from New York who migrated south with Congress. Property owners spiked room and house rentals, sometimes more than doubling the former rates, much to the congressmen’s annoyance. Carpenters rushed to build more accommodations, not just for Congress and the federal government, but for all the many artisans and shopkeepers who followed behind. Congressmen, however, found the city filled with commodities they could send home to grateful families, and many amusements—libraries, theaters, gardens, spas, balls, a museum, and constant invitations for socializing.

Congress convened on December 6, 1790, in the third session of the First Congress. Sixty-five members of the House sat in curved rows facing the Speaker. Twenty-six senators (two from each of thirteen states) climbed the steep staircase to their desks that faced Vice President John Adams, until his election to the presidency in 1797. When the 1790 Federal Census (Congressional Act in March 1790) increased the number of representatives to 105, the city enlarged the building to make room for the new members. The Senate grew as well, from 26 to 32 members, as Congress admitted three new states—Vermont (1791), Kentucky (1792), and Tennessee (1796).

To handle the heavy load of business, Congress created the first standing committees—commerce, banking, taxes, and the national debt. Early in 1791, Congress passed the act incorporating the hotly debated Bank of the United States, which carried the federal debt until its 20-year charter expired. In 1792, Congress passed the Coinage Act that created the first U.S. Mint, which was built in Philadelphia. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton had masterminded the details for this legislation, to secure a stable economy, regular debt payment, and a unified currency for the nation.

Matters concerning slavery did not meet with similar success. Although Congress limited American participation in the trafficking of slaves by passing the Slave Trade Act in 1794, petitions against the institution of slavery that the Quakers and the Pennsylvania Abolition Society had presented to Congress in New York made no headway on the floor. Certain southern delegates threatened that their states would abandon the union if the subject came to a vote. In 1793, Congress instead passed the Fugitive Slave Act that strengthened the terms for returning runaways established by the Constitution. Petitions against slavery never came to debate, including one in 1799 submitted by members of Philadelphia’s free Black community. The fate of the nation’s enslaved people remained a topic too difficult for Congress to address.

Protecting the Frontier

Congress tackled multiple obstacles to make the Western frontier safe. The Senate ratified and the House funded peace treaties with Native Americans, Spain, and England to settle the issues. After years of resistance to white settlement, Indians of the Ohio Valley met defeat at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 and agreed to a treaty. Spain’s troublesome control of New Orleans and navigation along the Mississippi found resolution with the ratification of the Pinckney Treaty in 1796. By far the most controversial treaty during the decade was with England. Relations had deteriorated while British troops remained in western forts in blatant violation of the terms provided in the 1783 Treaty of Paris, and as English ships continued seizing American cargo in the West Indies. A treaty with Great Britain negotiated in 1794 by Chief Justice John Jay aroused stiff public resistance that inflamed partisan animosities at home. Republicans in Congress railed against it, each state hotly debated its worth, and demonstrators marched in protest. When President George Washington showed his approval, the Federalists gained popular support and the Senate finally ratified it in 1795. House Republicans tried to block funding for the treaty, but failed, and the House finally voted its financing.

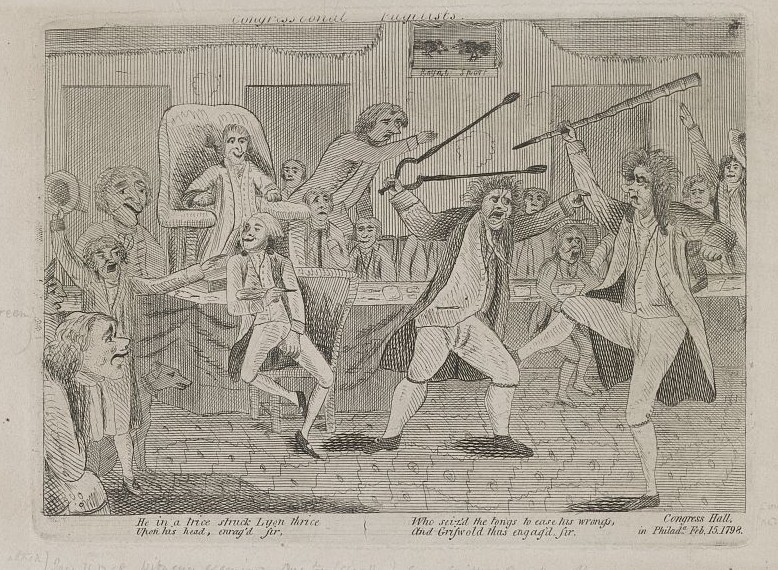

By the close of the decade politics had become rife with personal attacks in the halls of Congress and in the press. Partisan newspapers, discreetly funded by party leaders, lashed out at their political opponents, incensing public opinion and demonstrations. There seemed to be no limit to the slander and the animosity printed in the Federalist and Republican press.

When the nation unexpectedly faced the threat of war with France (the Quasi-War), however, the patriotism of citizens dampened the strident political rivalry. With war pending, the Fifth Congress, still dominated by Federalists, passed the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798 to control aliens in the country and suppress opposition or threats to the Adams administration. Republicans immediately denounced these four laws on the grounds they were unconstitutional, and the party leadership (Thomas Jefferson and James Madison) anonymously published the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions in protest. The resolutions contributed to the election of Jefferson as president in 1800. The turbulent decade of Federalist reign had ended, but not without a record of impressive accomplishments in forming and securing the emerging nation.

Coxey Toogood is a Historian in the Cultural Resources Management Division of Independence National Historical Park. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University