Bicentennial (1976)

Essay

Planners of Philadelphia’s Bicentennial celebration in 1976, aware of the incredible success of the 1876 Centennial as well as the flop of the 1926 Sesquicentennial, hoped to showcase the growth and ambitions of the city while also commemorating the two-hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. While the big celebrations drew crowds of Americans, the summer of ’76 also produced conflict and ultimately failed to fulfill the dreams of the city and its planners.

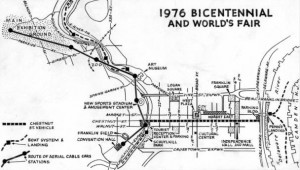

In the early 1960s, more than a decade in advance of the event, city planning director Edmund Bacon initiated bold plans for a Bicentennial commemoration with an additional element: a world’s fair. He wanted to use the nation’s birthday and the international profile of the world’s fair—and the federal dollars these would bring—to advance the agenda of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission. Bacon imagined a thorough redevelopment of the waterfronts in Center City, as well as a “midway” concept that would close Chestnut Street to vehicles except for open-side electric streetcars. An overhead tram would move visitors across the Schuylkill to fairgrounds in Fairmount Park, the same location as the Centennial of 1876.

In short order, however, the initial planning group and Bacon’s early vision were pushed aside by a vocal coalition of architects, planners, and reformers billing themselves as the “young professionals.” Including figures like attorney Stanhope Browne (b. 1931), editor Herbert Lipson (b. 1929), and architect Richard Saul Wurman (b. 1935), this group advocated a much grander concept, a model city built on a four-mile “megastructure” to be constructed above the Pennsylvania Railroad yard on the west bank of the Schuylkill. Meanwhile, planning also grew tense around the lack of inclusion of African Americans in the process. In response, the Bicentennial Corporation appointed Catherine Sue Leslie, a housing reform activist, to lead the “Agenda for Action.” This initiative aimed to include minority voices in Bicentennial planning, and Leslie developed a low-cost rival vision for the Bicentennial built around a scattered-site concept that would highlight the racial and ethnic diversity of Philadelphia.

At the national level, in 1966 the Lyndon B. Johnson administration created the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission (ARBC), which was charged with making site recommendations as well as content and funding decisions. In Philadelphia, meanwhile, a Bicentennial Corporation was chartered in 1967 and began working to raise funds, gather public support, and elaborate the theme and design elements of the Bicentennial and world’s fair. Philadelphians also sought to gain a competitive edge over Boston, a rival for the celebrations.

100 Million Visitors Anticipated

In 1969 a Philadelphia delegation presented the ARBC with its “Toward a Meaningful Bicentennial” plan, with the megastructure at the center and five different “core” areas in the city to demonstrate innovative ways to solve America’s urban problems. Anticipating an estimated 100 million visitors, the projected costs totaled more than a billion dollars. The ARBC rejected the plan, and in Philadelphia a bitter divide developed along racial lines over the thematic focus and the location. By 1972 progress was stalled, and Mayor Frank Rizzo (1920-91) canceled the world’s fair bid entirely, leaving only the Bicentennial commemoration to go forward. On the national level, the ARBC encouraged celebrations throughout the nation, not just in Philadelphia.

A year packed with Bicentennial-themed events began on New Year’s Eve, 1976, as thousands came to Philadelphia to witness the Liberty Bell being moved from Independence Hall to a new pavilion on Independence Mall. From January through October daily events included activities such as puppet shows, street theater, and concerts. The city hosted the NCAA Final Four tournament as well as all-star games for professional baseball, basketball, and hockey. The week leading up to July 4 was named Freedom Week and featured even more daily celebrations, street parties, parades, picnics, and concerts. A 2076 time capsule was buried at Second and Chestnut Streets, a 50,000-pound Sara Lee birthday cake was served at Memorial Hall, and fireworks filled the sky throughout the week.

On July 4, 1976, a ceremony on Independence Mall featured President Gerald Ford, Pennsylvania Governor Milton Shapp (1912-1994), and Philadelphia Mayor Frank Rizzo, with actor Charlton Heston as the master of ceremonies. Following the ceremony a five-hour parade featured floats from every state and 40,000 marchers. An estimated two million visitors came to Philadelphia to attend these events. On July 6, Queen Elizabeth II of Great Britain visited and, with Prince Philip, presented a Bicentennial Bell made in the same foundry as the original Liberty Bell.

During the year-long celebration, Valley Forge, up to this time a state park, became Valley Forge National Historical Park. On July 3, the winter campsite of George Washington’s Continental Army served as final destination for a commemoration of the westward wagon treks of the nineteenth century. Six wagon trains totaling 200 wagons, which had traveled for months from all over the nation, converged in Valley Forge in front of a crowd of nearly a half a million people.

Counter-Demonstrations

Along with the patriotic events came counter-demonstrations. Two groups of Philadelphia citizens, the July 4th Coalition and Rich Off Our Backs Coalition, staged marches and demonstrations during Freedom Week to oppose the celebration. Their plans prompted Mayor Rizzo to request 15,000 federal troops to maintain order, a request that was denied. Despite Mayor Rizzo’s concerns, the demonstrations in Fairmount Park and Norris Square Park were peaceful.

Philadelphia’s Bicentennial celebration concluded to mixed reviews. The event introduced many thousands of Americans to the urban renewal and historic preservation successes of the postwar period in the city. The three blocks composing Independence Mall were added to Independence National Historical Park in 1973, and historic buildings in the park were refurbished. The Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum, now the African American Museum in Philadelphia, and the Mummers Museum both opened in 1976. The Port of History Museum on Penn’s Landing at Walnut Street was designed as a Bicentennial gift from the state to the city, but it did not open until 1981. The Society Hill neighborhood, Elfreth’s Alley, and Penn’s Landing were all popular sites during the celebration.

While Freedom Week brought large crowds to Philadelphia, attendance at Philadelphia’s historical sites dropped quickly afterward. The total number of visitors to Philadelphia in 1976 was estimated to be between 14 and 20 million, which fell far short of the planners’ expectations. Much of the shortfall may be attributed to fear of violence spread by media attention to the protests and the mayor’s reaction to them. During the Bicentennial there was also an outbreak of Legionnaire’s Disease. Hundreds of members of the American Legion staying at the Bellevue Stratford Hotel contracted an infectious disease through the hotel’s air conditioning system, killing more than thirty of the Legionnaires.

Despite Philadelphians’ initial visions for a transformative event, the planning price tag of more than $50 million may have been too high considering the lack of long-term benefits. Features that were meant to bring lasting value, like a Living History Center or the Chestnut Street Transitway, were considered a thorn in the city’s side just five years later. It would be hard to imagine a more challenging period of time—with civil rights struggles, the Vietnam War, and Watergate fresh in mind, and the effects of racial strife, white flight, crime, and deindustrialization apparent in American cities—to hold a patriotic celebration. Philadelphia could not alter the calendar or reshape the larger context of the Bicentennial year.

Madison Eggert-Crowe is a graduate of Drexel University (2010) and is pursuing her Master’s in Public Administration at University of Pennsylvania’s Fels Institute of Government. Scott Gabriel Knowles is associate professor of history at Drexel University. He is the author of The Disaster Experts: Mastering Risk in Modern America (2011) and Imagining Philadelphia: Edmund Bacon and the Future of the City (2009). (Authors’ information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.