Classical Music

Essay

Classical music stands apart from vernacular (or “folk” music) and from “popular” music (in the form of simplified commercial entertainment) in its complexity of structure and high level of performance requirements. Philadelphia established a major position in American classical composition and performance in the early nineteenth century, and maintained that position through its premier professional orchestra (the Philadelphia Orchestra, founded in 1900) and its elite music schools.

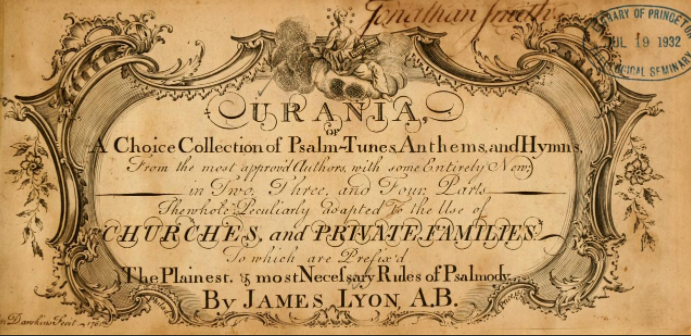

In planning a Quaker “holy experiment” on the Delaware River, William Penn (1644–1718) did not expect it to include music. But Quaker migrants were vastly outnumbered by German, Welsh, and other English settlers with no attachment to Quakerism and who had large community investments in musical performance, especially in the context of religious worship. Swedish Lutherans installed an organ in their first parish church, Gloria Dei, for use in services in 1700, and by the 1740s, Philadelphia’s German-speaking Moravians employed not only organs, but supporting instrumental bands of violins, oboes, flutes, and clarinets. The publication of religious music began in 1761, when James Lyon (1735–94) published the first native Philadelphia musical imprint, Urania, or A Choice Collection of Psalm-Tunes, Anthems, and Hymns. Andrew Adgate (1762–93) organized a short-lived Uranian Academy in Philadelphia in 1784 to promote church music.

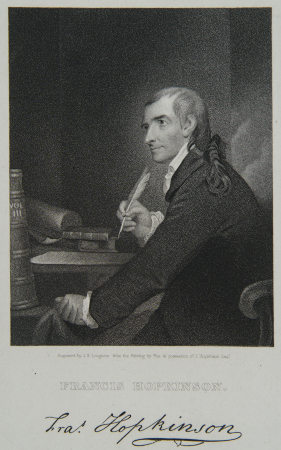

Secular classical music performance soon followed religious performance. Philadelphia’s first opera production, Alfred, by Thomas Arne (1710–78), was staged in 1757, and “subscription concerts” of secular music appeared in 1764. The first secular compositions published in Philadelphia came from the pens of lawyer and amateur musician Francis Hopkinson (1737–91) and Alexander Reinagle (1756–1809), who composed the earliest sonata-form music in Philadelphia for keyboard, his four “Philadelphia Sonatas,” in 1786. Raynor Taylor (1747–1825), who had been Reinagle’s teacher in London, followed his pupil to Philadelphia in 1792 and wrote the two most outstanding operas of the federal period, Pizarro, or The Spaniards in Peru (1800) and The Aethiop, or The Child of the Desert (1814). John Bray (1782–1822) composed The Indian Princess (based on the Pocahantas legend) in 1808, after moving to Philadelphia from the Royal Theatre in York, England, in 1805. Benjamin Carr (1768–1831), a prolific composer of sonatas, marches, and overtures, was the early republic’s most successful music publisher. They were joined by Charles Hommann (1803–72?), who made the first large-scale effort at American symphonic composition in the 1830s, writing a four-movement symphony in E flat, along with overtures, three string quartets, and a string quintet.

Development of Orchestras

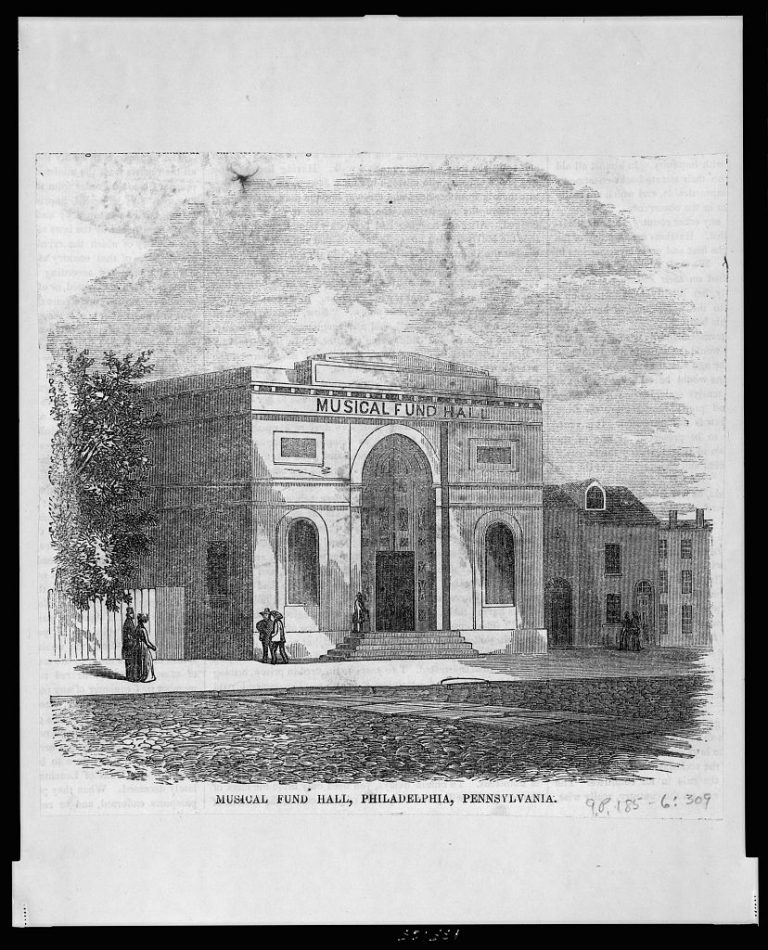

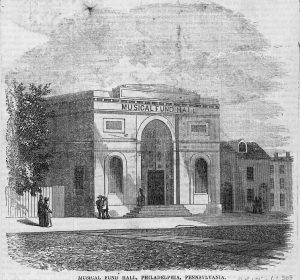

Orchestral concertizing in Philadelphia developed out of the small-scale ensembles of musicians hired to accompany plays and operas. None of them achieved much permanence until 1820, when Carr, Taylor, Hommann, and Hommann’s brother-in-law, Charles F. Hupfield (1822–95), founded the Musical Fund Society. The society offered its inaugural concert on April 24, 1821, at Washington Hall, on Third near Spruce Street, with a small orchestra of strings, flutes, and bassoons. In 1824, the society erected its own concert hall (on a design by William Strickland [1788–1854]) at Eighth and Locust Streets and gave its first concert there on December 29. A year later, the society organized a small music school to train new players. But by 1831, the music school had petered out, and although the society’s orchestra had risen in number to sixty-four players and programmed Philadelphia premieres of Beethoven symphonies, Haydn and Handel oratorios, and Weber and Mendelssohn overtures, it could not compete with the popular passion for imported Italian opera companies and celebrity performers from Europe—Ole Bull (1810–80) in 1845, Jenny Lind (1820–87) in 1850 and 1851, Henriette Sontag (1806–54) and child prodigy Adelina Patti (1843–1919) in 1852, Louis Antoine Jullien (1812–60) and his touring orchestra in 1853.

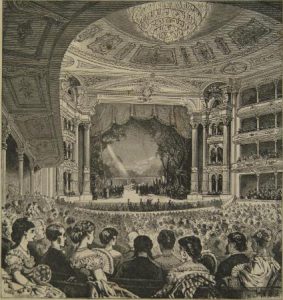

Operatic performance received further encouragement in Philadelphia from the construction of the new opera house at Broad and Locust, the Academy of Music, designed by Napoleon Le Brun (1821–1901) after the pattern of Milan’s La Scala. For two decades, until 1873, the Max Maretzek (1821–97) Italian Opera Company was the primary performer at the Academy of Music. It also played host to a variety of performance groups, including, from 1864 until 1891, the touring orchestra led by Theodore Thomas (1835–1905). But opera, beginning with Verdi’s Il Trovatore in 1857, dominated the stage, and in 1889, New York’s Metropolitan Opera began offering weekly performances, including Philadelphia’s first complete Ring des Niebelungen cycle.

One of the most successful of the touring orchestras was the Germania Musical Society, and in 1856, as the Musical Fund Society’s orchestra spluttered into oblivion, a local Germania Orchestra was organized in Philadelphia to showcase German classical music. The Germania mustered twenty-eight musicians, conducted by Carl Sentz (1828–88), Charles M. Schmitz (1824–1900), and William Stoll (1847–1910). The orchestra drew on Philadelphia’s large German immigrant community—the fourth-largest in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century—for both audiences and membership, and relied on a heavily Germanic repertoire, from Mendelssohn to Lizst, until it, too, folded in 1895. It was quickly succeeded by a new professional orchestra, known as the Thunder Orchestra from its conductor, Henry George Thunder (1865–1958), which performed at Musical Fund Hall, and by an amateur orchestra, the Symphony Society of Philadelphia, under William Wallace Gilchrist (1846–1916), who also directed choirs at Philadelphia’s Holy Trinity Church, St. Mark’s Church, and St. Clement’s Church.

In 1899, an eighty-member Philadelphia Symphony Society was organized to perform benefit concerts for widows and orphans of U.S. soldiers in the Spanish-American War, and from these concerts, a permanent Philadelphia Orchestra was created in 1900, which gave its first concert at the Academy of Music under the direction of German-born Fritz Scheel (1852–1907) on November 16. After Scheel’s sudden death, he was succeeded by Karl Pohlig (1864–1928), and then in 1912 by the flamboyant Leopold Stokowski (1882–1977), who began a comprehensive campaign to restock the orchestra with first-line players and introduced a dizzying varieties of daring premieres—Gustav Mahler’s Symphony of a Thousand in 1916, Alexander Scriabin’s Poem of Ecstasy in 1919, Igor Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps in 1922, and Arnold Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder in 1932. Stokowski led the Philadelphia Orchestra in the first commercially sponsored orchestral radio broadcast in 1929. Stokowski also pioneered the orchestra’s first recordings, beginning in October 1917, with acoustic recordings of Brahms’ Hungarian Dances No. 5 and No. 6 for the Victor Talking Machine Company in neighboring Camden (released commercially in 1918).

The Philadelphia Orchestra’s place as one of the “Big Five” American orchestras (beside New York, Boston, Cleveland, and Chicago) was extended through the long directorship of Eugene Ormandy (1899–1985, director 1938–80), but began to falter under the controversial leadership of Ricardo Muti (b. 1940, director 1980–92) and Christoph Eschenbach (b. 1940, director 2003–8). Further criticism pursued the orchestra when it moved in 2001 from the Academy of Music to a new performance venue, the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, whose acoustics were considered inferior. In April 2011, the orchestra was forced to file for bankruptcy protection; it emerged from the proceedings in July 2012, only after reorganization of the orchestra’s endowment and pension fund and substantial concessions by claimants and the orchestra’s musicians.

Music Education

The principal partner of the orchestra in Philadelphia’s classical music world was the Curtis Institute of Music, founded in 1924 by Mary Louise Curtis Bok (1876–1970), a major supporter of the orchestra. Not only did the orchestra’s principal players teach at Curtis, but Curtis supplied a major portion of the orchestra’s recruits (Mason Jones [1919–2009], principal horn, 1938–78; John de Lancie [1921–2002], principal oboe, 1954–77; Anshel Brusilow [b. 1928], concertmaster, 1959–66). Curtis also trained a series of prominent instrumental soloists conductors and composers.

However, the Curtis Institute was not the first major music education enterprise in Philadelphia. It was preceded by the Zeckwer Academy, founded by Richard Zeckwer (1850–1922) in 1870 at Twelfth and Spruce Streets, which merged in 1917 with the Hahn Conservatory, founded by Frederick Hahn (1869–1942), to become the Zeckwer-Hahn Philadelphia Musical Academy, and then simply Philadelphia Musical Academy (PMA). Two of the most important names associated with PMA were the composers Marc Blitzstein (1905–64) and Leo Ornstein (1893–2002). The academy merged in 1962 with yet another music school, the Philadelphia Conservatory of Music (founded 1877, at 216 S. Twentieth Street). PMA eventually retitled itself as the Philadelphia College of Performing Arts in 1976 just before it merged with the Philadelphia Dance Academy. Finally, after another series of mergers, it was reinvented yet again in 1987 as a college within the University of the Arts, at Broad and Pine Streets. The Academy of Vocal Arts, at Nineteenth and Spruce, was founded in 1934 to offer training in opera (and operatic languages) and voice, and counts among its prominent alumni Joyce DiDonato (b. 1969) and Joy Clements (1932–2005).

The city’s universities also have also been home to music departments with substantial performance reputations, especially the Boyer College of Music and Dance at Temple University, created in 1962, and the music department of the University of Pennsylvania, founded in 1875 by Canadian-born Hugh Archibald Clarke (1839–1927), who also wrote several outstanding textbooks in musical theory: A System of Harmony (1901), Counterpoint Strict and Free (1901), and Harmony on the Inductive Method (1880). The New School of Music, founded by Max Aronoff (1906–81) in 1943 and housed from 1968 at Twenty-First and Spruce Streets, concentrated exclusively on training orchestral musicians and was absorbed in the creation of Temple’s Boyer College in 1985.

Younger musicians enjoyed participation in orchestral performance through the Youth Orchestra of Philadelphia (beginning in 1939) and the Settlement Music School, which was originally a project by Jeanette Selig Frank (1886–1965) and Blanche Wolf Kohn (1886–1983) in 1908 to provide music education to the school-aged children of immigrant communities in Southwark. Settlement operated multiple branches throughout the city for musically gifted children.

The Curtis Institute and the city’s universities and colleges have been home for a number of prominent twentieth-century Philadelphia-based composers. Curtis trained Gian Carlo Menotti (1911–2007), Lukas Foss (1922–2009), Jennifer Higdon (b. 1962), and especially Philadelphia’s own Vincent Persichetti (1915–87) and Samuel Barber (1910–81). Harl McDonald (1899–1955), the director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Music Department, composed four symphonies (1932–35) and a concerto for two pianos; his successor, George Rochberg (1918–2005), wrote six symphonies, Cheltenham Concerto (1958), and seven string quartets. Louis Gesensway (1906–76) wrote the only distinctively Philadelphia-themed symphonic work, The Four Squares of Philadelphia, for narrator and orchestra, in 1955.

Other Classical Organizations

Opera in Philadelphia enjoyed more numerous but more short-lived incarnations. Three separate Philadelphia Grand Opera Companies attempted to attract audiences between 1916 and 1932. The New York operatic entrepreneur Oscar Hammerstein (1895–1960) built a Metropolitan Opera House on North Broad Street in 1908 to house an experiment he christened as the Philadelphia Opera Company, but the company survived for only two years. Sylvan Levin (1903–96) organized a second Philadelphia Opera Company in 1938, but it closed in 1944. Fourteen years later, the Philadelphia Lyric Opera Company launched yet another effort to establish a regular opera presence in Philadelphia with a production of Giacomo Puccini’s La Boheme—which also served as its last opera production in 1974, when the Lyric Opera merged with its rival, the Philadelphia Grand Opera Company, which had originally debuted in 1924 as the La Scala Grand Opera Company. The merger, originally known as the Opera Company of Philadelphia, renamed itself in 2013 as Opera Philadelphia.

The Philadelphia Chamber Music Society, founded in 1966 by Anthony Checchia (b. 1930), and the thirty-three-member Philadelphia Chamber Orchestra, founded by Marc Mostovoy (b. 1942) in 1964 as the Concerto Soloists of Philadelphia, offered full seasons of small-ensemble performances. In the late twentieth and into the twenty-first century, The Mendelssohn Club, Choral Arts Society, and the Singing City Choir, along with numerous city church choirs, provided musical performance outlets for both professional and amateur singers.

Radio broadcasts have been an important adjunct to classical performance in Philadelphia. An all-classical commercial radio station, WFLN (an acronym for the station’s parent owner, the Franklin Broadcasting Company), went on the air on March 14, 1949. Through live broadcasts, its large recorded library, talk-show interviews by host Ralph Collier (1922–2013), and its monthly magazine, the WFLN Philadelphia Guide, WFLN provided performance announcements, music advertising, and an on-air musical community. However, Philadelphia’s major public radio outlet, WHYY, abandoned its classical broadcasts in 1990, and WFLN experienced a series of sales of the station that resulted in its conversion from classical to heavy-metal rock in September 1997. This left classical music only part-time outlets through the Temple University public radio station, WRTI, and the University of Pennsylvania’s WXPN (which also subsequently dropped classical programming in favor of experimental pop fare). However, between 2012 and 2016, the Philadelphia Orchestra, WWFM/The Classical Network, and WRTI developed high-definition broadcast and streaming services, moving classical music in Philadelphia out of the world of analog broadcasting to digital.

The constituency for classical music in Philadelphia shrank in the twenty-first century, as in other places, as the costs of classical musical education and performance increased. The ease with which “pop” music dominated the performance and broadcast landscapes also made the complexity of classical music less attractive. Private funding for classical music by wealthy individuals, which was the norm in Philadelphia in the first half of the twentieth century, and from public sources—in school curriculums and municipal subsidies—diminished substantially. In an era of reduced public profile, classical composition and performance in Philadelphia became increasingly the preserve of academic environments.

Allen C. Guelzo is the Henry R. Luce Professor of the Civil War Era at Gettysburg College. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Despite financial difficulty, orchestra plays on (WHYY, April 18, 2011)

- Philly kids offer 'building blocks' for classical music, ballet (WHYY, October 5, 2011)

- New era begins for Philadelphia Orchestra (WHYY, January 25, 2012)

- Chubby Checker sings praises of Settlement school's music lessons for low-income kids (WHYY, March 7, 2012)

- Winners of Philadelphia classical music competition perform at the Kimmel (WHYY, October 28, 2016)

- With $2.5 M, seeking to discover Philly's next classical generation (WHYY, June 15, 2017)