Magazines, Literary

Essay

Philadelphia-based writers and publishers produced literary magazines as early as the 1740s, and, through the nineteenth century, the city was home to a succession of influential publications that supported many local authors and contributed to the establishment of a national literary culture. However, Philadelphia’s greatest prominence in literary publishing was achieved through a series of mass-circulation magazines for middle-class readers, especially women, from the 1830s through the first half of the twentieth century. Gradually, the influence of Philadelphia was diminished by the concentration of publishers elsewhere, primarily in New York, and by competing forms of mass entertainment such as radio and television. Through all those changes, however, Philadelphia sustained a remarkable wealth of societies and academic institutions that fostered the creation of lesser-known literary magazines, reflecting the communities that produced them. In the twenty-first century, with the rise of the Internet, Philadelphia writers gained the ability to exert a global influence unconstrained, as in the past, by the limits of printed publication.

Literary magazines, though they may include a variety of contents, typically are oriented towards the appreciation of artful writing. For most of their history, they were sold at newsstands and bookstores or sent through the mail by subscription. Wider circulation depended on reductions in printing costs and upon the creation of distribution networks. Their gradual, somewhat halting, emergence in the eighteenth century coincided with the growing demand for them created by an expanding middle class with aspirations towards social mobility and the education and resources needed for leisure reading. Literary magazines developed from a culture of genteel amateurism, with authors who were typically lawyers, ministers, and doctors pursuing an avocation, towards a profession that, at its peak, built publishing empires that employed thousands of workers. Perhaps more important, literary magazines helped to create a national culture and, at the same time, to challenge its dominant values.

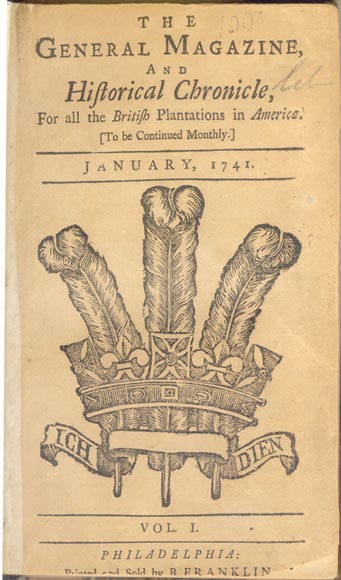

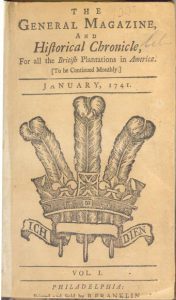

Philadelphia’s first literary magazines in the eighteenth century struggled to find an audience and did not last long. The Gentleman’s Magazine, published in London beginning in 1731, was a model for Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) to follow, a decade later, in his experimental General Magazine and Historical Chronicle for All the British Plantations in America. Sold in print shops, the General Magazine was a miscellany of republished essays, historical sketches, dialogues, and controversies. Not immediately profitable, it only lasted six issues. William Bradford (1719-91), the nephew of Franklin’s old rival Andrew Bradford (1686-1742), made another attempt in 1757 with The American Magazine, or Monthly Chronicle for the British Colonies. Edited by William Smith (1727-1803), the first provost of the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania), The American Magazine gathered a coterie of largely anglophile writers, including Francis Hopkinson (1737-91), Joseph Shippen (1732-1810), and Thomas Godfrey Jr. (1736-63), who wrote the first drama by an American author to be performed on stage, The Prince of Parthia (1767). The American Magazine mixed politics and poetry, and sought to explain the New World to the mother country; it only lasted for twelve issues, but it was a notable early flowering of the genre.

Port Folio

As the nation established itself in the early nineteenth century, literary magazines became more able to attract readers and sustain themselves. The Port Folio, founded in 1801 by Joseph Dennie (1768-1812) and edited under the pseudonym “Oliver Oldschool,” was a landmark in American literary history with a peak circulation of about two thousand, substantial for its time. It ran as a weekly until 1809, then mostly as a monthly until 1827. Initially, the Port Folio published poems, satires, translations, and literary essays; short stories and critical reviews came later in the series. Dennie was a Boston-born, Harvard-schooled lawyer—and, some would say, a fop—who sent annual birthday greetings to King George III. The Port Folio’s contributors often were drawn from the Tuesday Club, composed of young professionals from prominent local families: Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844), Horace Binney (1780-1875), Charles Brockden Brown (1771-1810), Thomas Cadwalader (1779-1841), John Ward Fenno (1778-1802), Joseph Hopkinson (1770-1842), Charles Jared Ingersoll (1782-1862), John Blair Linn (1777-1805), Richard Rush (1780-1859), and Robert Walsh (1784-1859). Other notable contributors included John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), William Dunlap (1766-1839), Thomas G. Fessenden (1771-1837), and Royall Tyler (1757-1826).

Federalist in outlook, neoclassical in taste, imitative of Joseph Addison (1672-1719) and Oliver Goldsmith (1728-74), and dismissive of romantic poets such as William Wordsworth (1770-1850) and Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834), the Port Folio also opposed American populism, regarded the American and French Revolutions as illegitimate, and accused Noah Webster (1758-1843) of promoting the decline of the English language with his American dictionary. Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) was a favorite target for the Port Folio’s ridicule. In 1803 Dennie was charged with seditious libel; he became less incendiary after his acquittal in 1805. Dennie died in 1812, and after a transition period the Port Folio was edited by John E. Hall (1783-1827). During those years, The Analectic Magazine, edited from 1813 to 1815 by Washington Irving and then by Thomas Isaac Wharton (1791-1856), a former associate of Dennie’s, also published a miscellany of increasingly original book reviews, translations, and naval biographies that became known for its engraved illustrations. It lasted until 1821, supported by its own circle of genteel amateurs. Meanwhile, the Port Folio, always struggling financially, never reclaimed the vitality and influence that it formerly held. It turned nationalistic, accelerated by the War of 1812, became supportive of more self-consciously American writers, and began to include engravings, all changes suggestive of what lay ahead for literary publishers.

Several Philadelphia literary magazines navigated the turbulent decades from the 1820s to the 1850s by becoming more commercially savvy: hiring full-time editors, purchasing more original content, nurturing professional writers, and orienting their publications toward developing markets at the national level. Even so, literary publishing remained a risky business. Different approaches were tried, but most failed to last long. Some took the high road. The American Quarterly Review, edited by Robert Walsh (formerly of the Tuesday Club) from 1827 to 1837, was sometimes described by later scholars as “dull” or “establishment.” Modeled on the famous Edinburgh Review and Boston’s North American Review, though favoring more regional authors, The American Quarterly Review addressed a wide range of subjects—politics, poetry, history, biography, science, and fiction, including writers such as Brown, Irving, and James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851)—with the ponderous severity of critical professionals, including George Bancroft (1800-91), George Ticknor (1791-1871), and James Kirke Paulding (1778-1860). The Review’s standards were derived from older European models, opposed to romanticism, and there were feuds between reviewers over the newly ascendant writers appearing in New York magazines such as William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878) and N. P. Willis (1806-67). When Walsh retired from the editorship in 1836, his son quickly reversed that perspective, embracing the romantics. Still, The Review closed within a year, having done much to make Philadelphia seem like a conservative backwater relative to New York and Boston.

Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine

At nearly the same time, in 1837, Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine began its three-year run, edited by William Evans Burton (1804-1860), a British-born actor, and assisted for a time by Edgar Allan Poe (1809-49). Burton’s covered art, literature, theater, and sports, as well as providing advice to young men. Poe wrote severe criticism of his literary contemporaries and contributed “The Fall of the House of Usher” and “William Wilson” among other original works. In 1841 Burton’s merged with a successful magazine primarily for women called the Casket: Flowers of Literature, Wit, and Sentiment, a publication started in 1826, that had been bought by George Rex Graham (1813-94). Together, Burton’s and the Casket became Graham’s Lady’s and Gentleman’s Magazine, which eventually achieved a national circulation of about forty thousand. Graham’s published poetry, biographical sketches, book reviews, literary criticism, and short stories, including Poe’s “Murders in the Rue Morgue” and “The Mask of the Red Death.” Unlike most literary magazines, Graham’s paid well and attracted American contributors such as Bryant, Cooper, Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-94), Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-82), Lydia Sigourney (1791-1865), and Willis. Abolitionists were not included; Philadelphia courted a readership in the South. Unlike The American Quarterly, Graham’s was accessible to more casual and increasingly female readers, much to Poe’s displeasure. It also pioneered the use of original engravings, including some by John Sartain (1808-97), who had his own publication, Sartain’s Union Magazine of Literature and Art, edited by Caroline Kirkland (1801-64) and Reynell Coates (1802-86); it ran briefly from 1849-52 and drew upon many of the same authors as Graham’s, most notably Poe (who provided his poem “The Bells” and a critical essay, “The Poetic Principle”).

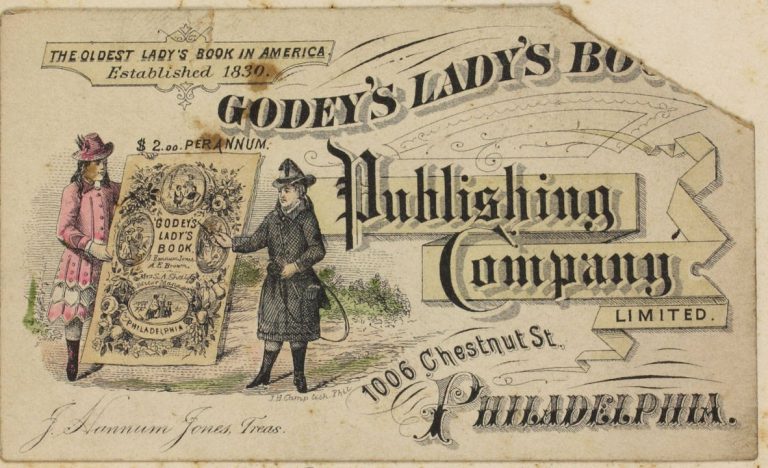

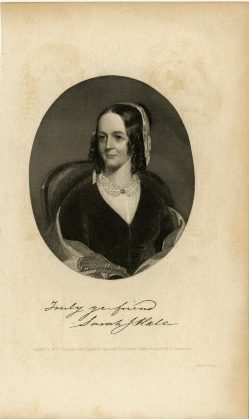

By the mid-nineteenth century, a design had emerged for the most successful magazines, aimed primarily but not exclusively at the middle-class female reader, with a wide range of literary content, including the original work of new and established American writers in many genres and an increasing quantity of visual material, most notably colored fashion plates. Louis Antoine Godey (1804-78) achieved an even larger scale of success than Graham: Godey’s Lady’s Book, a monthly launched in 1830, was the most widely circulated magazine in the United States before the Civil War. An essential component of that success was Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1879), who edited Godey’s from Boston from 1837-41, then came to Philadelphia in 1841 to be more directly hands-on, and remained editor until 1877, as the publication grew from a circulation of 10,000 to 150,000. Like Graham’s, it paid well, and, beginning in 1845, Godey’s was the first to provide copyright protection. It championed the work of women writers such as Kirkland and Sigourney, publishing them, and many others, with writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-82), Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-64), Holmes, Irving, Longfellow, Paulding, Poe, William Gilmore Simms (1806-70), Bayard Taylor (1825-1878), and Willis. Godey’s was not self-consciously highbrow, nor was it aesthetically avant-garde or politically radical. It was not directed primarily at male readers, but it published some of the leading authors of its time to the largest audience of its time. Godey’s had a major impact on U.S. cultural practices—helping to invent Thanksgiving and Christmas observances—and it pioneered the construction of what came to be called middlebrow culture. However, its apolitical stance during the Civil War harmed its circulation (Sarah Jane Lippincott, “Grace Greenwood” [1823-1904], was fired for having anti-slavery views), and it increasingly could not compete with better-illustrated publications such as Harper’s.

After Hale’s departure, the magazine lost even more ground to local rivals, such as Peterson’s Magazine, which Graham had launched in partnership with Charles Jacobs Peterson (1818-87) in 1842 to compete more directly with Godey’s by offering similar content at a lower price. Peterson’s (before 1855 it was Peterson’s Ladies’ National Magazine) also contained fashion plates and was an important publisher of women authors such as Rebecca Harding Davis (1831-1910), Francis Sargent Osgood (1811-50), and E.D.E.N. Southworth (1819-99). During the Civil War, Peterson’s overtook Godey’s, with a circulation of about 165,000 in the 1870s, but, by the 1890s, both had lost much of their audience and relocated to New York, where they were absorbed by other magazines.

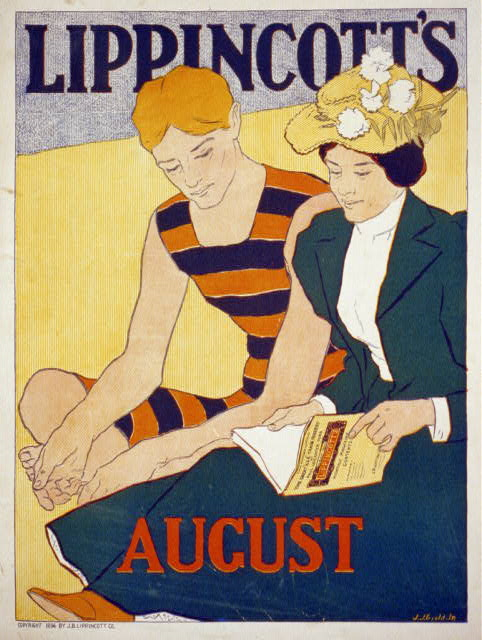

Cultivating Writers at Lippincott’s

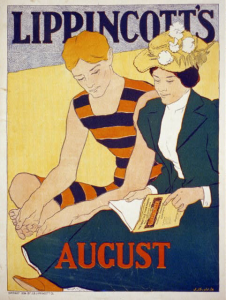

A similar fate befell Philadelphia’s Lippincott’s Magazine of Literature, Science and Education, which first appeared in 1868, published by Joshua Ballinger Lippincott (1813-86) and edited by John Foster Kirk (1824-1904) and, for a time, by William S. Walsh (1854-1919), the grandson of Robert Walsh, editor of The American Quarterly. From its inception, Lippincott’s aimed for a higher level of literary distinction than Godey’s and Peterson’s; it invested less in visual content (dropping it entirely in 1885) and competed more directly with The Atlantic, Boston’s premier literary magazine and arbiter of taste. It also was more friendly to writers of the American South and Middle Atlantic. Publishing serialized fiction, short stories, travel writing, poetry, and literary criticism, Lippincott’s cultivated a new generation of still-recognizable American writers, including Willa Cather (1873-1947), Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906), Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904), Henry James (1843-1916), Emma Lazarus (1849-87), Sidney Lanier (1842-81), S. Weir Mitchell (1829-1914), Frank Stockton (1834-1902), and Owen Wister (1860-1938), as well as English writers such as Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), and Oscar Wilde (1854-1900). Perhaps more than any other Philadelphia publication, Lippincott’s achieved a lasting reputation as a literary magazine of the first rank, nationally, but in 1914 it, too, moved to New York, which had emerged as the indisputable capital of U.S. publishing, where it became McBride’s before it was merged with Scribner’s in 1916.

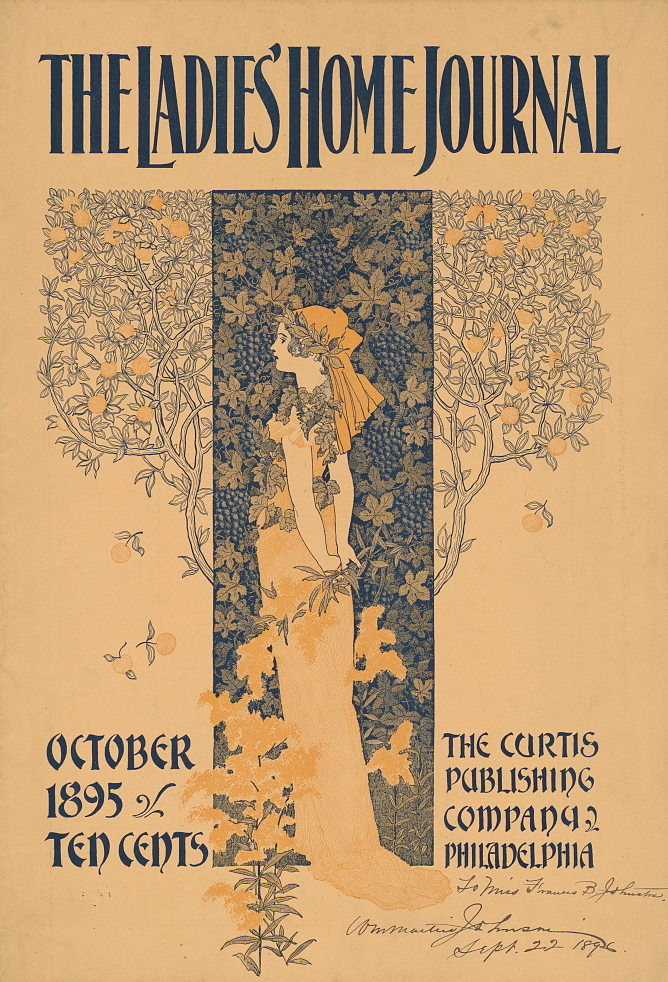

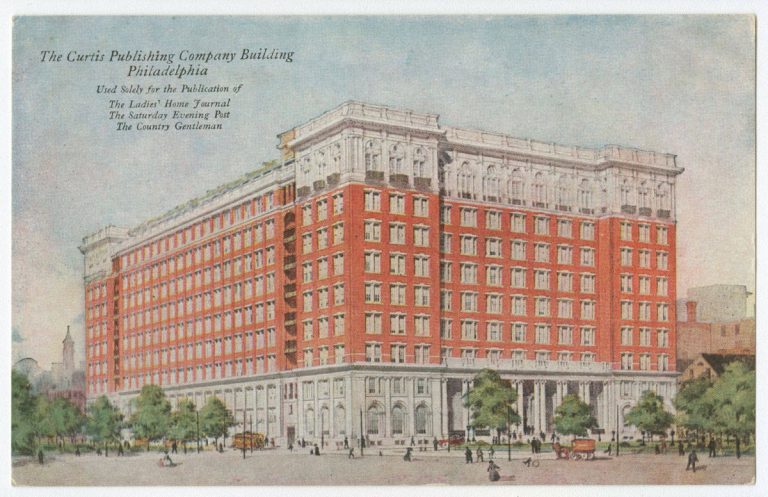

Less intellectual than Lippincott’s but financially far mightier, lasting well into the twentieth century, was Curtis Publishing, whose enormous Beaux Arts building, built in 1910, continued to preside over the southwest corner of Independence Square for more than a century. The company originated during the 1876 Centennial, when Cyrus H. K. Curtis (1850-1933) moved a newsmagazine called The People’s Ledger from Boston to Philadelphia, where printing was cheaper. The Ladies’ Home Journal, first edited by his wife, Louisa Knapp (1851-1910), started as a supplement to Curtis’ Tribune and Farmer. By 1886 it was an independent magazine. It had at least 270,000 readers when Knapp was succeeded by Edward W. Bok (1863-1930) in 1889. Bok soon became their son-in-law and the most influential editor in the United States; by 1903, the Ladies’ Home Journal had more than a million readers. Genteel, progressive, and elevated in a middle-brow way, Bok was a pioneer in the use of advertising and attracted writers such as Marion Crawford (1909-88), Hamlin Garland (1860-1940), Joel Chandler Harris (1848-1908), William Dean Howells (1837-1920), Sarah Orne Jewett (1849-1909), Mark Twain (1835-1910), James Whitcomb Riley (1849-1916), Kate Douglas Wiggin (1856-1923), and even Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), who became Bok’s friend. A few, such as Howells, Jewett, and Twain remained prominent in American literary history for realism, local color, and humor. Bok also employed famous illustrators such as Charles Dana Gibson and Howard Pyle. The Ladies’ Home Journal changed American domestic architecture, coining the “living room” and promoting suburban development. By 1919, when Bok retired in the wake of women’s suffrage, which he opposed, the Journal had more than two million readers, more than any other magazine up to that time. Circulation continued to grow, but the next half century marked a gradual decline in status for the Journal. Eleanor Roosevelt (1884-1962) became a contributor, so did Edna Ferber (1885-1968), but it increasingly seemed out of step with the times. It was something one’s elders read, and the movies and television seemed more engaging to more people. Curtis sold it in 1968, and, after multiple redesigns, it continued as an unpretentiously popular magazine. The Ladies’ Home Journal, like Godey’s and Peterson’s, had many male readers, and part of its decline owed something to the stricter segmentation of the market for readers by gender.

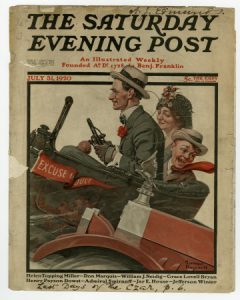

The Saturday Evening Post

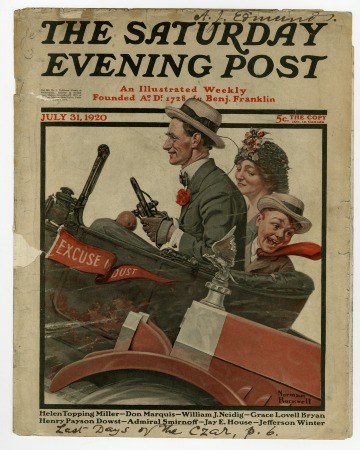

The Saturday Evening Post had a long local history, possibly going back to 1821, but Curtis Publishing made it nationally popular as a more masculine or at least family-oriented counterpart for The Ladies’ Home Journal in 1897. It serialized The Call of the Wild by Jack London (1876-1916) in 1903 and later became known for covers by Norman Rockwell (1894-1978). It eventually published writers such as Ray Bradbury (1920-2012), Agatha Christie (1890-1976), William Faulkner (1897-1962), F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940), Sinclair Lewis (1885-1951), Dorothy Parker (1893-1967), John Steinbeck (1902-1968), and Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007), but, by the end of the 1960s, when it, too, was sold, the Saturday Evening Post had become a byword for the “square” and “corny” among the younger generations of readers. Philadelphia-based magazine publishers never again attained the national status and influence that they held between the 1850s and the 1950s, but the literary culture of the city continued to grow and, in many respects, to reclaim its origins in smaller publications and coteries supported by academic institutions and private societies. Penn Monthly, first edited by Robert Ellis Thompson (1844-1924) in the 1870s, continued in the early twenty-first century as an online publication, The Penn Review, affiliated with the Kelly Writer’s House at the University of Pennsylvania, with an extensive program in support of creative writing and scholarship. Nearly every college and university in Philadelphia, especially those with Master of Fine Arts programs, launched its own literary magazine: Crimson and Gray at Saint Joseph’s University, StoryQuarterly at Rutgers University-Camden, and TINGE Magazine at Temple University represented the genre. Many of those magazines had long histories of print publication, but increasingly they published only online. Beyond the many publications sponsored by institutions of higher learning, the literary scene in Philadelphia grew to include several notable journals, such as The American Poetry Review, founded in 1972, which became the most widely circulated poetry magazine in the U.S., also publishing literary essays, translations, fiction, reviews, and interviews. Other publications included Painted Bride Quarterly founded in 1973, the Philadelphia Poets Journal, founded in 1980, and Schuylkill Valley Journal and the Mad Poets Review, both launched in 1990. Philadelphia Stories began publishing local writers in 2004, and Apiary first appeared in 2009.

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries the Internet disrupted publishing in ways that recalled the upheavals of the mid-nineteenth century. Many magazines closed or abandoned print entirely, but literary culture continued to expand and develop new audiences, mediums, and styles. At the same time, digital archives made the literary history of Philadelphia, in all its complex forms and intersecting communities, more accessible than ever for readers and scholars.

William Pannapacker, who holds a Ph.D. in American Civilization from Harvard University, is the DuMez Professor of English at Hope College. He is the author of Revised Lives: Walt Whitman and Nineteenth-Century Authorship (2004) and numerous articles and reviews on American literature and culture. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History