Philadelphia Contributionship

Essay

As North America’s longest continuously operating fire insurance company, The Philadelphia Contributionship for the Insurance of Houses from Loss by Fire (The Contributionship) affected the physical and economic development of Philadelphia and the region while simultaneously establishing modern insurance underwriting standards. Through its insurance operations, The Contributionship promoted fire safety, lent money for home mortgages, and invested capital in business ventures.

Before The Contributionship, attempts to establish a property insurer either failed or stalled. The first effort to form an insurance company collapsed after a calamitous fire in Charleston in 1740 overwhelmed South Carolina’s Friendly Society for the Mutual Insuring of Houses against Fire only five years after its inception. A decade after this catastrophe, the Union Fire Company in Philadelphia, founded by Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) in 1736 as an all-volunteer fire brigade, contemplated the next attempt at insurance coverage. The fire brigade’s members realized, however, that its small membership could not accumulate sufficient capital to fund the plan properly.

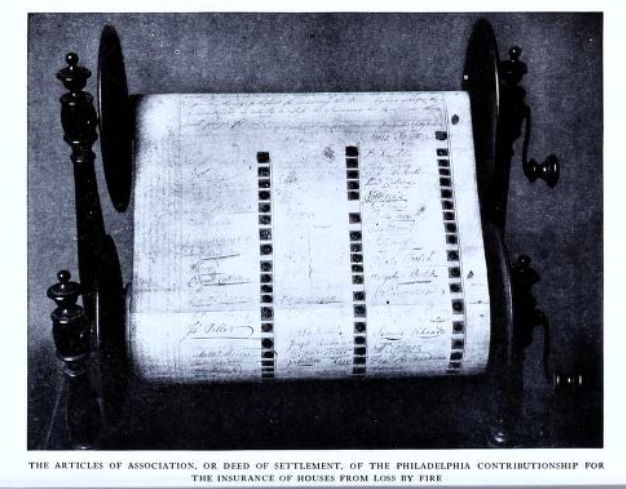

Despite abandoning its initial insurance plan in 1751, the Union Fire Company’s experiment introduced the idea of fire insurance to a wider network of prominent Philadelphians. During the early months of 1752, seventy-five of Philadelphia’s leading citizens subscribed to The Contributionship’s Deed of Settlement, or rules of operation, based on a similar framework for a London insurer, the Amicable Contributors. Following an advertisement in Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette, subscribers met at the Court House, then located at High (Market) and Second Streets, on April 13, 1752, to elect The Contributionship’s board of directors and first treasurer. Following this mutual commitment, The Contributionship formally incorporated in 1769 under existing Pennsylvania law.

Influence on Construction and Landscaping

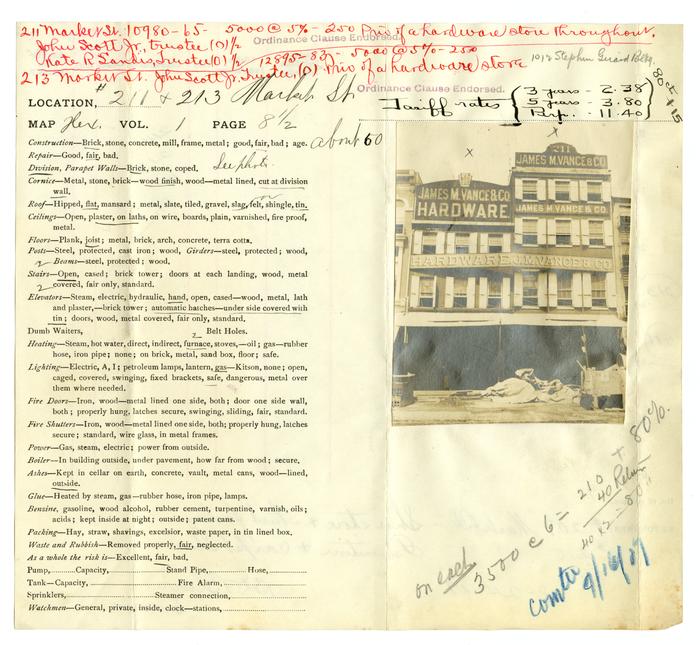

The Contributionship intended to reduce fire hazards through its conservative rules of operation and, consequently, influenced Philadelphia’s future construction and landscaping. The company limited its business range to within a ten-mile radius of Philadelphia, but only upon an acceptable written survey of the risk. Additionally, The Contributionship charged higher premiums for homes with commercial storefronts, such as chemists and malthouses. After 1769, the company’s refusal to insure wooden properties affected building practices by encouraging brick structures. By 1781, The Contributionship ceased insuring properties with shade trees due to their potential as fuel for fire and the inability of fire equipment to reach higher than one story. This decision fanned a disagreement between the company and subscribers who wished to keep trees on their properties. Faced with the denial of insurance coverage, those subscribers organized a rival insurance company willing to accept their trees and named it the Mutual Assurance Company, commonly referred to as the Green Tree, in 1784.

As The Contributionship accumulated deposits from its subscribers for insurance coverage, the company considered how to employ these funds without risking the capital necessary for a fire loss. Within a year of commencing business, the company’s board of directors began lending its subscribers’ deposits for mortgages at a 6 percent rate and received permission in 1809 from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to invest in stock companies, such as the Bank of North America. By the early nineteenth century, The Contributionship’s assets grew modestly thanks to its conservative underwriting philosophy and the city’s enhanced ability to fight fires with a more reliable water supply and better equipment. With significantly increased assets by 1835, The Contributionship expanded its investments to include ventures such as the Schuylkill Navigation Company and the Pennsylvania Railroad.

Beyond financial investments, The Contributionship played an active civic role in the Philadelphia region. As early as 1754, it erected stone mile markers from Philadelphia to New Castle, Delaware, and to New York for use by travelers and surveyors. Naturally, The Contributionship also sought to reduce fire hazards by donating funds for chimney sweeping and new fire equipment for fire brigades in Philadelphia.

In 1836, Finally, a Headquarters

Due to its fitful growth and a limited number of full-time employees, The Contributionship did not need rented office space initially, operating instead primarily from the homes of its treasurers until the early 1800s. With growing assets, the company considered purchasing a building for its headquarters as early as 1816. Yet, The Contributionship moved slowly with this effort until 1835, when new leadership sought to modernize the company’s operations, including the establishment of a suitable headquarters. The company’s directors commissioned the esteemed Architect of the United States Capitol, Thomas U. Walter (1804-87), to design a permanent home worthy of the company’s ascendant status. Construction of Walter’s Greek Revival style building at 212 S. Fourth Street finished in 1836. The Contributionship strategically selected this property because of its proximity to businesses helpful to the conduct of insurance, such as banks and brokerage houses. Other insurance companies, including the Green Tree, noted the convenience of this area and also located around Walnut Street between Second and Sixth Streets, which eventually became known as “Insurance Row.” Named a National Historic Landmark in 1979, The Contributionship’s headquarters afforded its treasurers and their families living quarters until 1894.

From its new headquarters, The Contributionship flourished throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century. Although the company rescinded its ten-mile geographic range in 1836, the company operated solely in Pennsylvania. Despite large claims from fires in 1839 and 1850, the company was able to maintain steady coverage to its members thanks to its conservative underwriting practices. During the Civil War, The Contributionship wholeheartedly sided with the Union’s cause and, again, demonstrated its commitment to civic engagement by purchasing war loans from the Federal Government and the State of Pennsylvania and donating to the Volunteer Refreshment Saloon to boost the troops’ morale. Recognizing the danger of inadequate deposits, The Contributionship continued to resist paying dividends until 1894 when it bowed to pressure from protesting subscribers and paid dividends for the first time since 1763.

Catastrophic fires in the cities of Baltimore and San Francisco in 1904 and 1906, respectively, convinced The Contributionship’s leadership to reduce the number of insured buildings in concentrated neighborhoods and to build its financial reserves through an increase in rates. Despite the rate hike, the fear of such fires encouraged more Philadelphians to seek coverage and The Contributionship’s business increased notably. Although refusing to write car insurance, the company recognized the popularity of automobiles, and, in 1909, agreed to extend fire coverage to the growing number of garages housing them. The company remained solvent through the stock crash of 1929 despite the need to foreclose on some of its real estate holdings. In the late 1940s, the company began covering hazards beyond fire for the first time, and in the 1970s and 1980s the company expanded into all lines of insurance. It also invested in non-insurance services, such as residential security, affiliated with its core home-protection business. The Contributionship expanded into the New Jersey market by the late 1990s, spreading 50 percent of the company’s risk profile into that market by 2002.

Fire Marks, a Sign of Protection

An enduring symbol of The Contributionship has been its fire mark, which the company issued to all policyholders starting in 1752. The practice of affixing a fire mark to a home’s façade to identify what fire company or insurer protected the home originated in London in the seventeenth century and continued in the American colonies. The Contributionship’s fire mark, commonly called the Hand-in-Hand, consisted of four gilded hands, each clasping a wrist of another hand to create a square of hands, on a black shield. The symbolism of the clasped hands, also known as the fireman’s carry, represented mutual support and linked The Contributionship to its origins with the Union Fire Company and the Amicable Contributors. The Contributionship ceased issuing fire marks with the advent of Philadelphia’s municipal fire department in 1871, which answered fire calls regardless of the home’s owner or insurer. Nevertheless, The Contributionship’s fire marks, and those of other insurance companies, remained visible on homes in Philadelphia and assumed a decorative role.

Over more than 250 years of continuous operation, The Contributionship modernized and adapted to respond to its subscribers’ demands as well as changes in the marketplace. Risk-related premiums and well-timed rate adjustments, both up and down, maintained the company’s solvency against competition and through wars and economic downturns, assuring its place in Philadelphia’s history.

Timothy J. Potero is a practicing attorney and M.A. candidate in Rutgers-Camden’s public history program.

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- "Fires, Fights and Benjamin Franklin: Philadelphia’s Volunteer Firemen" (PhillyHistory.org Blog)

- National Register of Historic Places Nomination: The Philadelphia Contributionship (National Park Service)

- Philadelphia Contributionship Digital Archives (Philadelphia Architects and Buildings Project)

- What Are Those Little Shields Above the Doorways of Philadelphia Homes? (Philadelphia Magazine)