Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania

By Andrew Heath

Essay

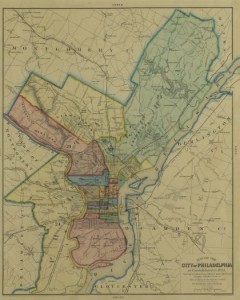

Dating to 1682, Philadelphia County’s founding coincided with the origin of the city. Although the county faded from view after its consolidation with the city in 1854, it remained important for understanding Philadelphia’s urban development, local government, and long battles for political reform.

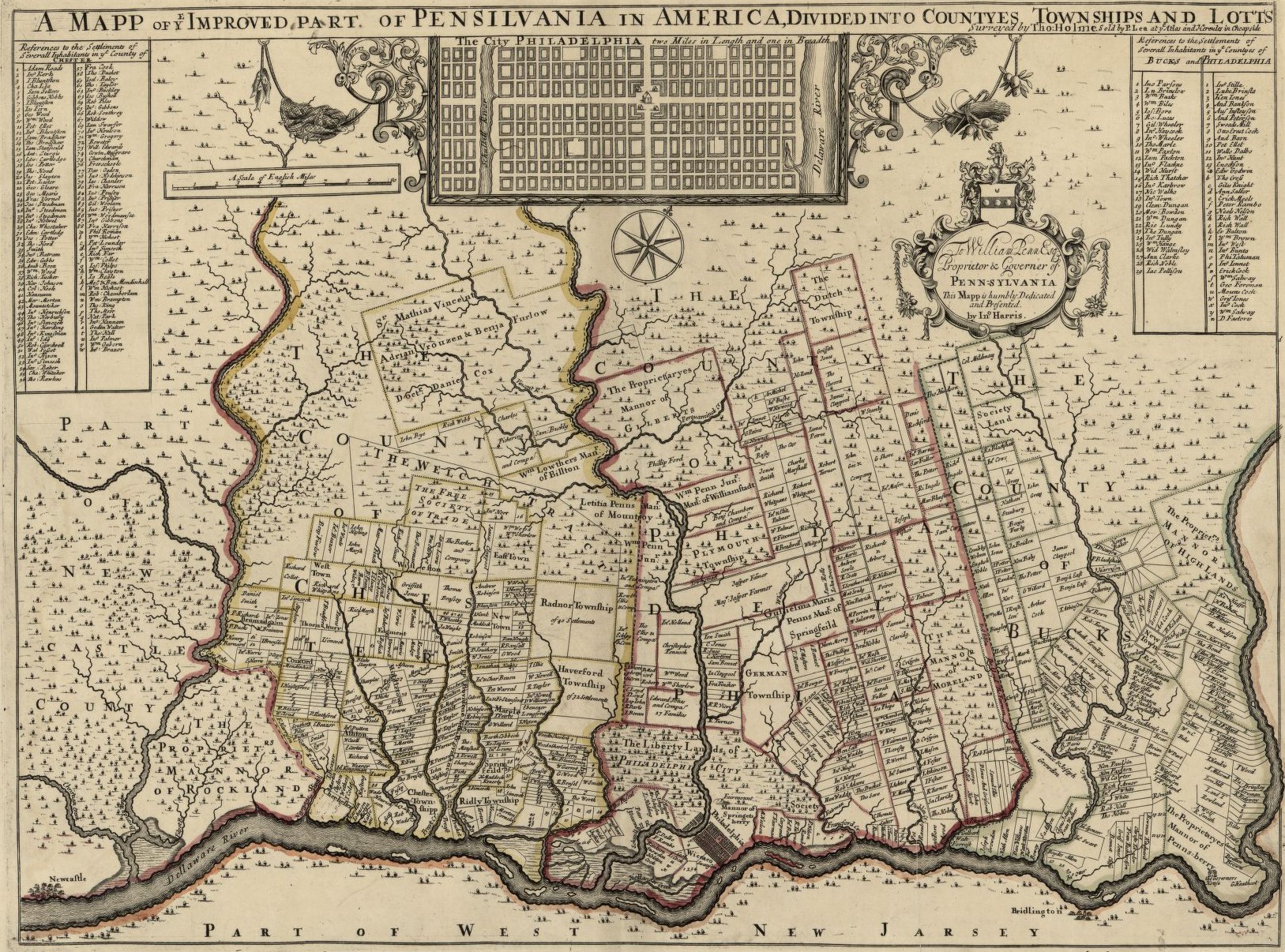

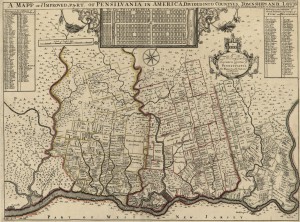

When founding Pennsylvania, William Penn (1644-1718) followed long-established precedent by dividing his province into counties. As an ancient jurisdiction, the county had roots in the shires of England’s Saxon earls. After the Norman Conquest of 1066, the shires became known as counties. Over the following centuries they became the primary administrative subdivisions for a growing state, and then in the American colonies beginning in Virginia in the 1630s. Penn followed suit, creating Philadelphia, Bucks, and Chester Counties in 1682.

Over the course of the eighteenth century the Provincial Assembly and Pennsylvania State Legislature altered Philadelphia County’s borders as the colony expanded. As colonists who had migrated westward petitioned for local governments of their own, portions of Philadelphia were sliced off to form Berks (1752) and Montgomery (1784) Counties. By 1800 Philadelphia County’s boundaries had been fixed in a manner that roughly corresponded to the future city limits, running along the Delaware River from southwest to northeast and stretching over the Schuylkill River to the west.

Local government in early Philadelphia County took place at three levels. Incorporated municipalities enjoyed rights granted by the proprietor, much in the manner of self-governing English towns. Within the county, the two-square-mile city of Philadelphia (1691) and Germantown (1691) each benefited from these privileges, although Germantown lost its charter in 1707 after devout Quakers and Pietists proved reluctant to hold local offices on religious grounds. Between that point and the Revolution, only Southwark (1762), which stood just to the south of the city proper, secured incorporation. Beyond these self-governing municipalities, county government held sway, with Philadelphia city serving as the seat. As the county covered a large rural area, it was subdivided into townships–twelve in all by 1718–that took on administrative roles. In Blockley, Bristol, and Byberry, for instance, township constables performed many of the same duties as Philadelphia’s sheriff.

County Politics

County government played an important role in the lives of the colonists. Together with its townships, it built and maintained highways, provided for the poor, preserved the public peace, prosecuted and punished offenders, and impounded stray animals. Like a chartered corporation, Philadelphia County could hold property and could sue and be sued. As the most visible form of local government, moreover, it became a political battleground. Despite holding Pennsylvania as a feudal estate, Penn and his heirs soon had to grant the province a measure of self-rule, which extended to counties and townships. Thus while a few county officers were directly appointed, voters usually had at least some say. The proprietor, for instance, chose the county sheriff, but only from the two leading candidates at the polls. Because a far higher proportion of Philadelphia’s rural men than their urban counterparts met the property qualification for voting, participation in county politics was common, including service as directly elected officials included property assessors and tax collectors.

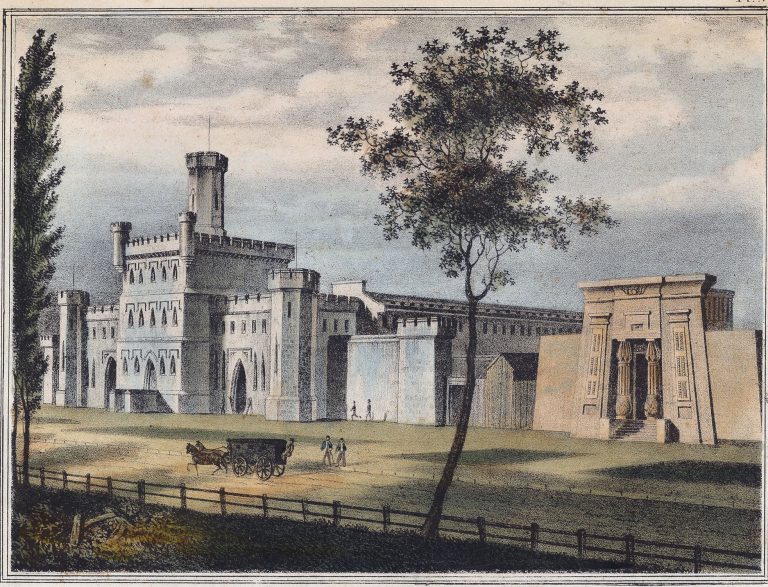

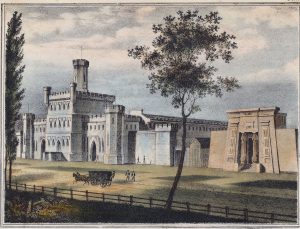

Colonial patterns persisted long after the proprietorship of the Penns. In the decades after American independence, growing parts of Philadelphia County sought incorporation as self-governing municipalities, a process that gathered pace in the Jacksonian era. Many of these municipalities, like Moyamensing and Kensington, stood on the edge of Philadelphia proper, separated from the city only by lines on the county map that were more imaginary than real. Others, notably Manayunk (1840) and a rechartered Germantown (1844), burgeoned as villages, miles from the growing metropolis. The vast majority of Philadelphia County remained rural, and in these areas county and township government appeared perfectly adequate, especially as more positions–including the sheriff from 1838–opened to direct election. County jurisdiction also extended into the incorporated municipalities. Residents of the city, districts, and boroughs voted for county officers and paid the county tax, which went toward the upkeep of highways, courts, bridges, and prisons; some of the biggest building schemes proposed around mid-century—including early plans for public buildings at the Broad and Market intersection—were county projects. Among such designs was Moyamensing’s imposing jail—designed by Thomas U. Walter (1804-1887), fourth architect of the U.S. Capitol building—which stood from 1835 until 1968.

Philadelphia’s “turbulent era,” however, exposed the limits of county government. Between 1828 and 1849 the city was wracked by riot after riot, including the anti-Catholic violence of 1844. Much of the trouble took place in the newly incorporated suburbs. Neither city nor suburbs maintained a modern police force prior to 1845, and when crowd action got out of hand, it usually fell on the sheriff, as traditional conservator of the peace, to restore control by raising a posse comitatus (“power of the county”). Although the sheriff’s powers were broad in theory (a judge in 1844 compared them to those of a dictator in the Roman Republic), they proved weak in practice. One Kensington strike in 1843 concluded with weavers turning on the sheriff, and a year later, after the posse proved unable to stop two major mobs, the county was placed under martial law. Attempts to improve the county’s response to rioting—notably an 1841 statute that made taxpayers liable for losses incurred during riots—had little impact, and instead citizens began to look to either the creation of a professional police force or the consolidation of the city and built-up districts into one municipal government.

As if to step into the vacuum created by the want of strong municipal authorities, the county became more assertive. In 1853, the County Commissioners tried to borrow $2 million to help fund a railroad to Lake Erie. Such actions, along with the money made in fees by county and township officers, drew censure from prominent citizens; one labeled the purchase of stock “the most flagrant act of injustice ever attempted.” Frustration at spendthrift officials swelled support for a consolidation, which, when it finally came in 1854, swallowed the entire county into the city.

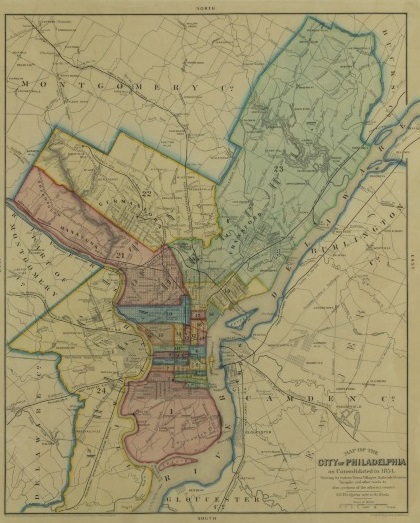

Consolidation’s Far-Reaching Effects

The extension of the city’s boundaries to embrace the county’s vast rural environs went far beyond the designs of most consolidators. Opposition to consolidation came largely from rural townships, where the routine work of maintaining highways and providing for the poor seemed a world away from the complex administration of a big city. In the years leading up to the Civil War residents in the remote northeast petitioned the state legislature to break away from the city and either form a new county or merge with neighboring Bucks; such secessionist sentiment in Philadelphia’s northeast persisted late into the twentieth century. But in 1854 consolidators promised county landowners spectacular returns on their property, lower rates of taxation, and the maintenance of separate poor boards. The mixture of incentives and concessions tempered hostility to annexation.

With the 1854 charter, Philadelphians were not quite sure whether city and county had become one and the same—even the architect of the Consolidation Act expressed his doubts, and the city commissioners retained a degree of independence from councils and the mayor—but the new charter seemed to have done its work. The county board disappeared, as did the townships, except for the purpose of providing poor relief. County officials came under the city’s control, including the county commissioners, who oversaw elections and tax collection. The county continued to play a role in the justice system, but the cost of maintaining courthouses and prisons fell on the city. A single municipal treasury had authority to raise taxes and disburse funds for city and county purposes.

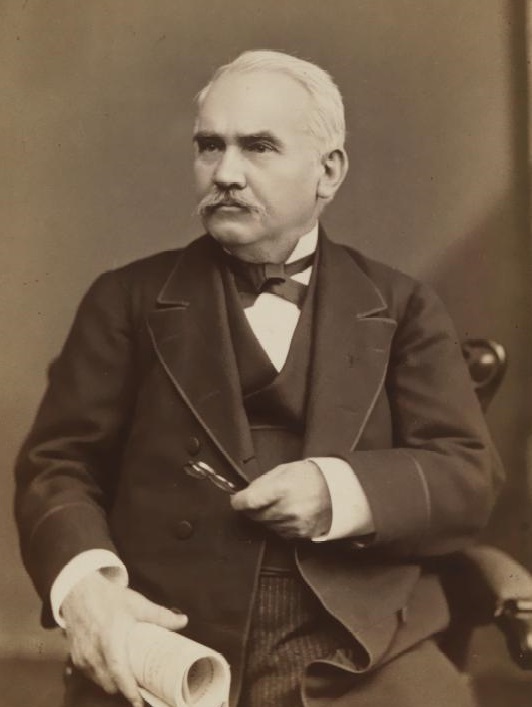

Yet in the late nineteenth century divisions between city and county began to reappear. The state constitution of 1874 made several offices—including commissioner and treasurer—county positions. Courts subsequently confirmed that these city officers under the Consolidation Act were constitutionally-protected county officials. To municipal reformers, such a seemingly academic distinction had serious political consequences. First, county officials could spend money of their own accord and then leave the bill with city government. This “mandamus evil,” as Progressive reformers called it, reminded residents of post-Civil War commissions that had similar powers to burden the municipal treasury. Second, elected county officials had access to a rich patronage pot and considerable income in the form of state-mandated fees. A new city charter in 1919 established a merit system for city employees, but as the county lay beyond its jurisdiction, jobs there could still go as political rewards. By the middle of the twentieth century, about a thousand county employees were excluded from Philadelphia’s civil service requirements. Long before then, however, county offices had become a boon to Republican bosses like Simon Cameron (1799-1899) and James McManes (1822-99).

Long Road to True Consolidation

The task of completing what one early twentieth-century critic called the city and county’s “half-hearted” consolidation preoccupied reformers from the Progressive era (c. 1890-1920) onward. The independent Bureau of Municipal Research, which acknowledged the “complicated and technical” relationship between the two governments, nonetheless argued in 1923 that the matter was “of sufficient importance to engage the attention of every citizen.” The bureau led the drive for “home rule”: a measure adopted in other states that gave cities the freedom to draw up their own charters without legislative interference. Calls for the consolidation of city and county offices accompanied the campaign. Given that the 1874 state constitution safeguarded county offices, this required a constitutional amendment, and a measure enabling such a reform failed in a 1937 referendum despite registering a large majority in Philadelphia.

In the post-World War II era reformers found friendlier terrain for consolidation. Democrats Joseph S. Clark (1901-90) and Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974) exposed swindling in the Republican city machine, and for once “corrupt and contented” Philadelphians responded. Civic organizations called for home rule and the merger of city and county functions. In 1951, they secured a home rule charter, and state voters approved an amendment allowing cities and counties to merge. By 1952, under the reform charter, the work of bringing county offices under city control was well underway.

Philadelphia’s first consolidation in 1854 had merged the territory of city and county; its second, almost a century later, brought their separate institutions together under unified control. The county “row offices,” though, did not disappear entirely. In 2017, the Sheriff, the City Commissioners, the Clerk of Quarter Sessions, and the Register of Wills remained a part of city government. Reformers saw them as expensive anachronisms. The Register of Wills, for instance, was just about the only part of the municipal apparatus exempt from Philadelphia’s civil service rules. Philadelphia County died as a unit of local government, but in pockets of City Hall its legacy lived on.

Andrew Heath is a Lecturer in American History at the University of Sheffield, United Kingdom. He is writing a book on the Consolidation of 1854.

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Philadelphia County (Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Lincoln Steffens, Excerpts from "Philadelphia: Corrupt and Contented," July, 1903 (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- How Philly Got Its Shape (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- In Defense of Consolidation (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Exhibit: Preserving the Legacy of Richardson and Dilworth (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)