Presidents of the United States (Presence in Region)

Essay

Presidents of the United States, seeing Philadelphia as the city most connected to American independence, often have turned to the city and region to campaign, advance their agendas, and commemorate the past. In the city where the nation’s first two presidents established the executive branch of government, presidential legacies have spurred commemoration as well as controversy.

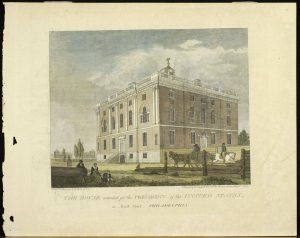

Philadelphia’s long association with the presidency began after the Residence Act of 1790 placed the federal government in the city for ten years, while work began on a new capital city on the Potomac River. Presidents George Washington (1732-99) and John Adams (1735-1826) resided and instituted the executive branch of government in a house at Sixth and Market Streets rented from financier Robert Morris (1734-1806).

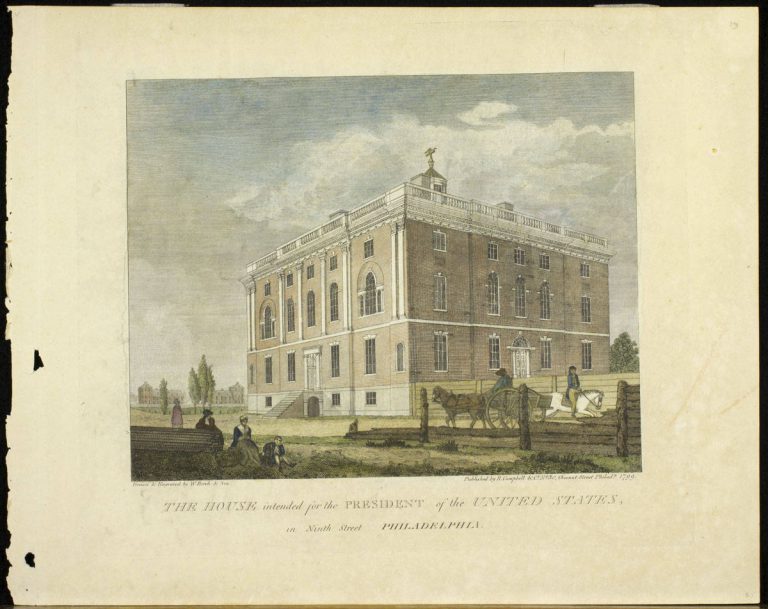

From the President’s House, Washington oversaw construction of the new capital and declined Philadelphians’ generous offer of a new, large presidential residence built on Ninth Street between Market and Chestnut. (Twice, during the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 and the hot summer of 1794, Washington opted for Germantown.) Guided by the U.S. Constitution drafted in Philadelphia in 1787, Washington established the role of the presidency. In 1792, for example, after conferring with his cabinet, Washington vetoed a bill (concerning apportionment of House seats) for the first time. One achievement was the 1795 ratification of the Jay Treaty, an attempt to settle lingering conflicts with Great Britain. Debates over the extent of the federal government’s powers led to the formation of political parties and contributed to Washington’s decision to step down after two terms, setting another precedent that lasted into the twenty-first century.

On March 4, 1797, John Adams took the oath of office in Congress Hall, becoming the first president sworn in by the chief justice. The peaceful transfer of power to another administration was especially significant for the young republic. Adams had to negotiate the ongoing development of the country’s first political parties, the Federalists (with which Adams identified), and the Democratic-Republicans, an opposition party led by Vice President Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826). Adams also confronted foreign policy problems with France, including the Quasi-War in 1798.

When Philadelphians received the news of George Washington’s death in 1799, the city joined Congress in formally mourning the founding father on December 26. A procession began at Congress Hall and led to Zion Lutheran Church, Fourth and Cherry Streets, for a service attended by Adams and conducted by Bishop William White (1748-1836).

Presidential Visits and Sites of Mourning

The departure of the federal government from Philadelphia to its permanent location in Washington, D.C., in 1800 did not sever the city’s connection to presidents. Philadelphia’s role as the birthplace of independence and the American government continued to draw attention from presidents who visited the sites associated with this history and invoked the nation’s founding documents in their speeches.

The first presidential visit came in 1817, only months after President James Monroe (1758-1831) took office and embarked on a goodwill tour of each state. A large crowd welcomed Monroe to Philadelphia on June 5. He addressed the veterans of the Pennsylvania Society of the Cincinnati and stopped at sites throughout the city, including Peale’s Museum, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Pennsylvania Hospital.

Presidents generally saw enormous, raucous crowds during official visits, particularly in the first part of the nineteenth century. This era witnessed a growing participation in politics, with the public drawn in particular to populist leaders who spoke out against the elite. One such figure, Andrew Jackson (1767-1845), appeared before thirty thousand at the Navy Yard on June 8, 1833. The following day, a mob poured into First Presbyterian Church, where Jackson attended services. The president visited Independence Hall on June 10, a year to the day after he vetoed the renewal of the charter for the Second Bank of the United States, located one block away on Chestnut Street. The mayor intended to host a small reception at Independence Hall, but crowds of uninvited guests eager to see Old Hickory broke in and quickly overcrowded the first floor. Some had to flee the onrush through windows.

The city hosted two memorials for deceased presidents. In 1848, John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) lay in state in Independence Hall, the first president to have the honor. Adams had served in the House of Representatives since 1831, the only person to do so after his presidency. Philadelphians paid respects to “Old Man Eloquent” as his remains were taken from Washington to Massachusetts for burial.

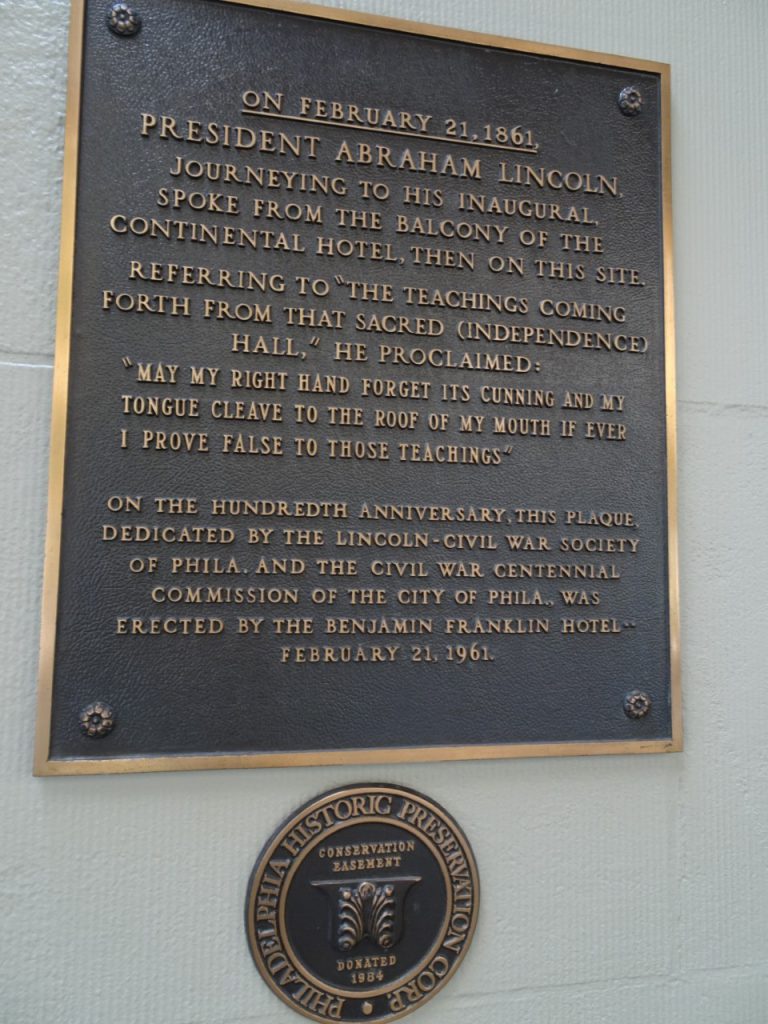

The only other president to lie in state at Independence Hall was Abraham Lincoln (1809-65). As president-elect in 1861, Lincoln passed through Philadelphia on his way his inauguration in Washington, D.C., and participated in the city’s celebration of Washington’s Birthday on February 22. He raised the flag over Independence Hall and spoke of Philadelphia as the birthplace of the Union. The thirty-four-star flag reflected the recent admission of Kansas after years of debates over slavery in the territories.

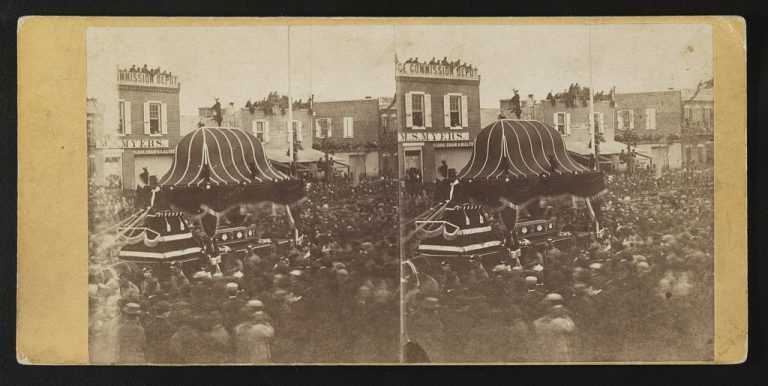

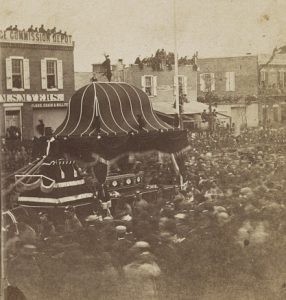

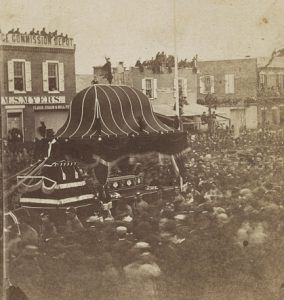

During the Civil War, Lincoln returned to the city to visit the Great Central Fair, a fund-raiser for the U.S. Sanitary Commission at Logan Square. Lincoln arrived on June 16, 1864, a day declared a local holiday. Less than one year later, Philadelphians assembled for Lincoln again, but in mourning. A train bearing Lincoln’s remains, en route to Illinois for his burial, arrived in Philadelphia on April 22, 1865. Mourners draped black bunting throughout the city and watched the funeral procession from rooftops. Ticketed guests paid respects to the slain president in Independence Hall that night, and the public viewing followed the next day. Crowds gathered as early as 4:30 in the morning; the doors opened at 6 a.m. An estimated 85,000 passed by Lincoln’s casket.

When a reunited nation celebrated the one hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence in 1876, the Centennial Exhibition brought President Ulysses S. Grant (1822-85) to Philadelphia. Together with Brazilian Emperor Don Pedro II (1825-91) and a number of European princes, Grant attended the opening festivities on May 10 and turned on the massive Corliss steam engine that ran the hundreds of machines on display. The technology displayed and the visit of Don Pedro (the first reigning monarch to visit the United States) captured the imagination of visitors, while the exhibition of George Washington’s uniform, camp set, and household items harkened back to an earlier, different, era.

The political activities of Philadelphia merchant John Wanamaker (1838-1922) led to another notable presidential visit. Wanamaker, who served as postmaster general under Benjamin Harrison (1833-1901), remained active in the Republican Party. He campaigned for William Howard Taft (1857-1930) and ultimately developed a friendship with the president. On December 30, 1911, Taft repaid Wanamaker’s service by dedicating the new Wanamaker Building at Thirteenth and Market Streets, the first time in history that a president dedicated a department store.

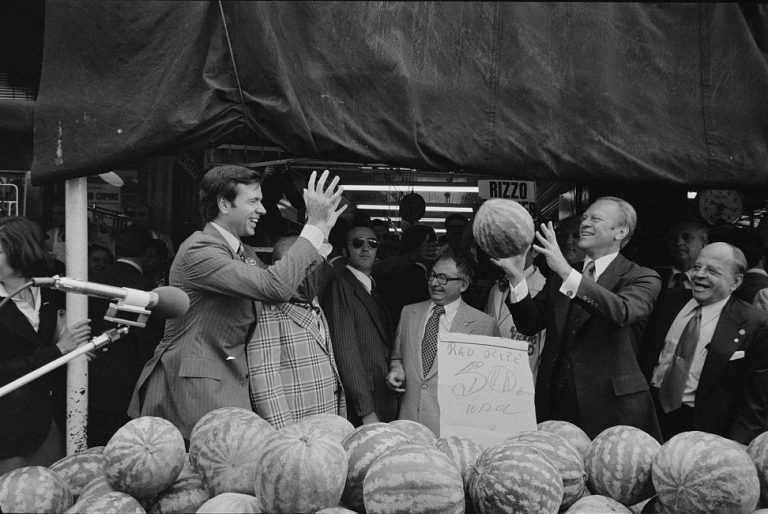

The nation’s birthday often served as an occasion for presidential visits and speeches referencing self-government and the freedom forged by the founders. In this tradition, President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) spoke at Independence Hall on July 4, 1914. This was Wilson’s second visit to the city in less than a year; the president also spoke at the rededication of Congress Hall on October 25, 1913. Both addresses called upon Americans to embrace the principles of the Founding Fathers, particularly the former speech, which focused on the idea of liberty. President Calvin Coolidge (1872-1933) participated in the 1926 festivities, which included a speech at Independence Hall and a visit to the Sesquicentennial Exposition. On July 4, 1962, President John F. Kennedy (1917-63) addressed a crowd at Independence Hall and tied the ideals of the Declaration of Independence to the Cold War, discussing American leadership in the fight for independence in nations under Communist control. Gerald Ford (1913-2006) and George W. Bush (b. 1946) were among the presidents who took part in July 4 events at Independence Hall.

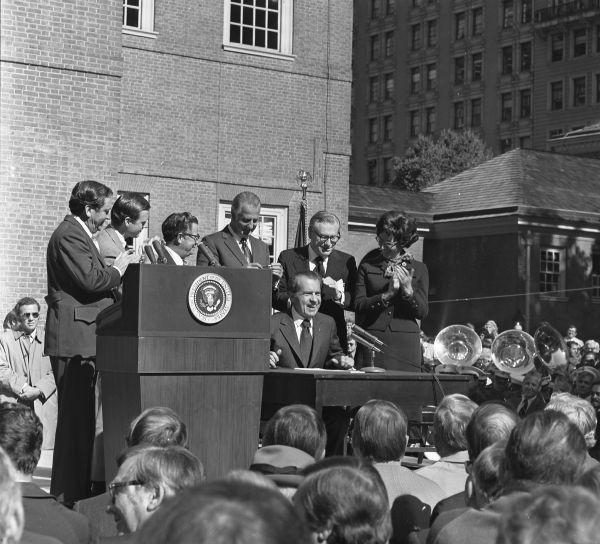

Ceremonial occasions were not the only times that presidents used language linking the present with the Revolutionary War era. For example, President Richard Nixon (1913-94) used Independence Hall as a backdrop to unveil his program for federal revenue sharing on October 20, 1972, claiming it presented an extension of principles established by the Founding Fathers.

The Campaign Trail

Philadelphia’s role in hosting political conventions also brought presidents—and potential presidents—to the city. From the Whig Party convention in 1848, which nominated Zachary Taylor (1784-1850), through the 2016 Democratic National Convention, twelve national party conventions convened in Philadelphia.

One of the most publicized of these events was the 1936 Democratic convention, which nominated Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) for a second term. In his acceptance speech, broadcast nationwide by radio, Roosevelt drew parallels between the American Revolution and his New Deal domestic programs, comparing concentrated wealth to the tyranny of British rule. Aware of the political situation in Europe, the president outlined the importance of American democracy as a counter to the rise of dictatorships in Europe. In 1948, the Republicans, Democrats, and the Progressives all held conventions in the city. That year, the Philadelphia Chapter of Americans for Democratic Action had a hand in crafting a strong civil rights platform for the Democrats, which led to a walkout of southern delegates.

The 1930s saw Pennsylvania shift from a Republican stronghold to a battleground state during presidential elections, largely because of the Great Depression. As Philadelphia also began to shift from a bastion of Republicanism to a solidly Democratic city, the city attracted numerous important campaign visits. Before losing the 1932 election to Roosevelt, Herbert Hoover (1874-1964) campaigned at Reyburn Plaza with an estimated one hundred thousand in attendance. In the 1960 campaign, both John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon blitzed the state. Later, Barack Obama (b. 1961) delivered a major address on race and American culture at the National Constitution Center in the 2008 campaign. In the twenty-first century, Philadelphia remained an important campaign stop.

Regional Ties

Presidential interest and influence in the region extended beyond Philadelphia. Two presidents had connections to Gettysburg, about 140 miles west of the city. Abraham Lincoln delivered his immortal Gettysburg Address there on November 19, 1863, and Dwight D. Eisenhower purchased a farm near the battlefield in 1950. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev (1894-1971) visited the Eisenhower farm on a state visit in 1959; the president presented the Soviet leader with a bull. James Buchanan (1791-1868) lived in nearby Lancaster, purchasing Wheatland, an estate a mile from the town, in 1848 near the end of his tenure as secretary of state. Wheatland witnessed lobbying by office seekers after Buchanan’s election in 1856, several visits from Buchanan in the ensuing years, and the fifteenth president’s retirement. Woodrow Wilson served as president of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, the culmination of his career as an academic political scientist, and as governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913, his first elected office.

Presidents have also found rest and relaxation in the region. Starting with Ulysses Grant in 1874, Atlantic City became a destination for vacationing chief executives. City officials were grateful for the national attention that accompanied these dignitaries. Harry Truman (1884-1972) and Dwight Eisenhower (1890-1969) enjoyed golfing at Stockton Seaview Hotel and Golf Club. For others, like John F. Kennedy, the city was a campaign stop. His successor, Lyndon B. Johnson (1908-73) was nominated for a full term at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City in 1964, though the event brought attention to the city’s then-seedy accommodations. In all, sixteen presidents stayed in Atlantic City before, during, or after their time in office.

Lyndon Johnson returned to New Jersey in 1967 for the Glassboro Summit. On June 23-25, Johnson met with Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin (1904-80) on the campus of Glassboro State College (later renamed Rowan University). Though the summit yielded little diplomatically, both sides were amicable and their meeting somewhat calmed Cold War tensions, at least temporarily.

Legacies and Controversies

The presidential presence in Philadelphia has been commemorated in many tangible ways. Plaques in the ground near Independence Hall marked the speeches made there by Lincoln and Kennedy. At the Wanamaker Building (Macy’s), an inscription in the floor marked where Taft stood to dedicate the building. Philadelphians placed a monument to Lincoln in Fairmount Park in 1871, and the Society of Cincinnati added a Washington monument in 1897 (moved in 1928 to the newly completed Benjamin Franklin Parkway). During the 1890s, the Fairmount Park Art Association also commissioned monuments to James Garfield (1831-81) and Ulysses S. Grant. Elsewhere in the city, a monument placed City Hall in 1908 honored William McKinley (1843-1901), and a state historical marker erected on Fourth Street in 1999 recalled the national mourning of Washington two centuries before. Several streets, including John F. Kennedy Boulevard and Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Boulevard, also have been named for presidents.

Philadelphia’s association with the early presidency forcibly came to public attention in the first decade of the twenty-first century in connection with the site of the President’s House occupied by Washington and Adams during the 1790s, which in the twentieth century became part of Independence National Historical Park. In 2002, research by independent historian Edward Lawler Jr. documented the history of the long-demolished house and outbuildings, including the presence of slaves brought from Mount Vernon to serve the Washington household. The findings made the public aware that Washington circumvented the 1780 Pennsylvania gradual abolition law by rotating the slaves between Mount Vernon and Philadelphia. This information, and knowledge of the presence of slavery only feet away from where a new Liberty Bell Center was to be built (it opened in 2003), led numerous interest groups to lobby for a commemoration of the President’s House that would recognize slavery. The result, an outdoor exhibit titled “The President’s House: Freedom and Slavery in the Making of a New Nation,” opened on December 15, 2010.

Controversy over a president’s legacy also erupted in 2015 at Princeton University, where Woodrow Wilson served as president. A group of Princeton students asked the university to remove Wilson’s name from its campus, including the Woodrow Wilson School of Public Policy and International Affairs, because of Wilson’s attitudes on race—for example, his actions in segregating the federal workforce. The university examined Wilson’s legacy and decided in April 2016 that the president’s name would remain. Princeton’s board of trustees called for a balance of recognizing not only Wilson’s successes but also his failures.

In the aftermath of these controversies, Philadelphia continued to play an important role in remembering key moments in the executive branch’s history, from its beginnings with the ratification of the Constitution and Washington’s two terms through visits by modern presidents like George W. Bush, who received the Republican nomination at the 2000 convention held in Philadelphia, and Barack Obama. In the twenty-first century, the rich history of the region continued to attract the country’s leaders, and Pennsylvania’s status as a battleground state assured further campaigning by candidates for the presidency.

Andrew Tremel is an independent researcher and public historian at the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Washington exhibit explores the good, the bad and the ugly (WHYY, June 30, 2011)

- President Obama taps Northwest Philadelphia for his re-election effort (WHYY, June 30, 2011)

- Obama headlines North Philly Wolf rally to energize Democrats in Pa. governor's race (WHYY, November 3, 2014)

- In Philadelphia, president vows to fight to protect Obamacare with a veto (WHYY, January 30, 2015)

- In Philly NAACP address, Obama calls for overhaul of criminal justice system (WHYY, July 15, 2015)

- Obama and friends capture the flag (WHYY, July 28, 2016)

Links

- PhilaPlace: The President's House: A Story of Our Nation's First White House (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Deshler-Morris House: Germantown White House Reinterpreted (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- National Funeral for President Washington (ExplorePaHistory.com)

- When Presidents Come to Town (The PhillyHistory Blog)

- Standing His Ground: Abraham Lincoln in Philadelphia (The PhillyHistory Blog)

- President Abraham Lincoln's Address at Independence Hall (February 22, 1861)

- President Benjamin Harrison's Remarks During Decoration Day Ceremonies in Independence Hall (May 30, 1891)

- President Woodrow Wilson's Address at Independence Hall: "The Meaning of Liberty" (July 4, 1914)

- President Calvin Coolidge's Address at the Celebration of the 150th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence (July 5, 1926)

- President John F. Kennedy's Address at Independence Hall (July 4, 1962)

- Vice President Lyndon Johnson delivering an Independence Day speech outside Independence Hall (July 4, 1963)

- 1967 Glassboro Summit (Rowan University via YouTube)

- President Richard Nixon's Statement About the General Revenue Sharing Bill (October 20, 1972)

- President Gerald Ford's Remarks on the Bicentennial Celebration (July 4, 1976)

- President George W. Bush's Remarks at an Independence Day Celebration in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (July 4, 2001)